Akut76004.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Lioconcha Castrensis Species Group (Bivalvia : Veneridae), with the Description of Two New Species

Molluscan Research 30(3): 117–124 ISSN 1323-5818 http://www.mapress.com/mr/ Magnolia Press The Lioconcha castrensis species group (Bivalvia : Veneridae), with the description of two new species SANCIA E.T. VAN DER MEIJ1, ROBERT G. MOOLENBEEK2 & HENK DEKKER2 1 Netherlands Centre for Biodiversity Naturalis (department of Marine Zoology), P.O. Box 9517, 2300 RA Leiden, The Nether- lands. Email: [email protected] (corresponding author) 2 Netherlands Centre for Biodiversity Naturalis (section Zoological Museum of Amsterdam), Mauritskade 57, 1092 AD Amsterdam, The Netherlands. Email: [email protected] Abstract Part of the genus Lioconcha Mörch, 1853 is reviewed. Species strongly resembling Lioconcha castrensis (Linnaeus, 1758) are discussed and two new species are described: Lioconcha arabaya n. sp. from the Northwest Indian Ocean and Lioconcha rumphii n. sp. from Thailand and Sumatra. These three species, together with Lioconcha macaulayi Lamprell & Healy, 2002, share many morphological similarities and we suspect them to be closely related. They are referred to as the Lioconcha cast- rensis species group. Furthermore, lectotypes of Venus castrensis Linnaeus, 1758, and Venus fulminea Röding, 1798, are desig- nated. The latter is considered a junior synonym of V. castrensis. Key words: Indo-Pacific, Mollusca, Persian Gulf, Red Sea, taxonomy Introduction between the anterior and posterior extremities, height is measured vertically from the umbo to the ventral margin and The delimitation within the tropical venerid genus Lioconcha total width (or inflation) is the greatest distance between the Mörch, 1853, is problematic, due to high levels of external surfaces of the paired valves. For an extensive list of intraspecific morphological variability and relatively few synonyms of figured specimens of Lioconcha castrensis we useful morphological characters (Lamprell and Healy 2002). -

Paleoenvironmental Interpretation of Late Glacial and Post

PALEOENVIRONMENTAL INTERPRETATION OF LATE GLACIAL AND POST- GLACIAL FOSSIL MARINE MOLLUSCS, EUREKA SOUND, CANADIAN ARCTIC ARCHIPELAGO A Thesis Submitted to the College of Graduate Studies and Research in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in the Department of Geography University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon By Shanshan Cai © Copyright Shanshan Cai, April 2006. All rights reserved. i PERMISSION TO USE In presenting this thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a Postgraduate degree from the University of Saskatchewan, I agree that the Libraries of this University may make it freely available for inspection. I further agree that permission for copying of this thesis in any manner, in whole or in part, for scholarly purposes may be granted by the professor or professors who supervised my thesis work or, in their absence, by the Head of the Department or the Dean of the College in which my thesis work was done. It is understood that any copying or publication or use of this thesis or parts thereof for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. It is also understood that due recognition shall be given to me and to the University of Saskatchewan in any scholarly use which may be made of any material in my thesis. Requests for permission to copy or to make other use of material in this thesis in whole or part should be addressed to: Head of the Department of Geography University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon, Saskatchewan S7N 5A5 i ABSTRACT A total of 5065 specimens (5018 valves of bivalve and 47 gastropod shells) have been identified and classified into 27 species from 55 samples collected from raised glaciomarine and estuarine sediments, and glacial tills. -

Shell Classification – Using Family Plates

Shell Classification USING FAMILY PLATES YEAR SEVEN STUDENTS Introduction In the following activity you and your class can use the same techniques as Queensland Museum The Queensland Museum Network has about scientists to classify organisms. 2.5 million biological specimens, and these items form the Biodiversity collections. Most specimens are from Activity: Identifying Queensland shells by family. Queensland’s terrestrial and marine provinces, but These 20 plates show common Queensland shells some are from adjacent Indo-Pacific regions. A smaller from 38 different families, and can be used for a range number of exotic species have also been acquired for of activities both in and outside the classroom. comparative purposes. The collection steadily grows Possible uses of this resource include: as our inventory of the region’s natural resources becomes more comprehensive. • students finding shells and identifying what family they belong to This collection helps scientists: • students determining what features shells in each • identify and name species family share • understand biodiversity in Australia and around • students comparing families to see how they differ. the world All shells shown on the following plates are from the • study evolution, connectivity and dispersal Queensland Museum Biodiversity Collection. throughout the Indo-Pacific • keep track of invasive and exotic species. Many of the scientists who work at the Museum specialise in taxonomy, the science of describing and naming species. In fact, Queensland Museum scientists -

Morphological Variations of the Shell of the Bivalve Lucina Pectinata

I S S N 2 3 47-6 8 9 3 Volume 10 Number2 Journal of Advances in Biology Morphological variations of the shell of the bivalve Lucina pectinata (Gmelin, 1791) Emma MODESTIN PhD of Biogeography, zoology and Ecology University of the French Antilles, UMR AREA DEV ABSTRACT In Martinique, the species Lucina pectinata (Gmelin, 1791) is called "mud clam, white clam or mangrove clam" by bivalve fishermen depending on the harvesting environment. Indeed, the individuals collected have differences as regards the shape and colour of the shell. The hypothesis is that the shape of the shell of L. pectinata (P. pectinatus) shows significant variations from one population to another. This paper intends to verify this hypothesis by means of a simple morphometric study. The comparison of the shape of the shell of individuals from different populations was done based on samples taken at four different sites. The standard measurements (length (L), width or thickness (E - épaisseur) and height (H)) were taken and the morphometric indices (L/H; L/E; E/H) were established. These indices of shape differ significantly among the various populations. This intraspecific polymorphism of the shape of the shell of P. pectinatus could be related to the nature of the sediment (granulometry, density, hardness) and/or the predation. The shells are significantly more elongated in a loose muddy sediment than in a hard muddy sediment or one rich in clay. They are significantly more convex in brackish environments and this is probably due to the presence of more specialised predators or of more muddy sediments. Keywords Lucina pectinata, bivalve, polymorphism of shape of shell, ecology, mangrove swamp, French Antilles. -

Performance of the New England Hydraulic Dredge for the Harvest Of'stimpson~Surf Clams

PERFORMANCE OF THE NEW ENGLAND HYDRAULIC DREDGE FOR THE HARVEST OF'STIMPSON~SURF CLAMS Inv d Experimental Biology Division*. Deparhnent of Fisheries and Oceans Canada Maurice Lamontagne Instihite 850 route de la Mer f O00 Mont-Joli (~uébec) G5H 324 Canadian Industry Report of isheries and Aquatic Sciences 235 ? nadian Industry Report of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences canaain the ~e?iaIts:Bf ramh and develotrment iradustq fof MkF irnmedia~elar Iutuw1appdkashn. They are da.r.ected pfimarbly tmard indiziduak .h $ha primary and secondary çccrors of the fishing and marine mduaries. ?i,o ratlrMhn k phced on sulbjmt mcta and the series reflects the broad inoemrs and p~2ek5&oh Department d Fisher& and Oceans. aamely. fishiesad aqwticsc+awe~,. .' 1t@u~rr5reprts m. be cimed & full pnsblicatbns. The cornkt citatian aowars . abri the abatracr of each report. Eacb rekl is a&rrxad in Awair %ie.nr& ifid . technical publicatio . Sumber;l-9li e lndustrial Devel- opsnent BranCh. Technical Reports of th. lndiausrrkf ikxelo~mentÉranch. a& - ,Tecknical Reports of the &-sk*an's Servk Branch. kumkrs 62- I tO Giztaisseed as . Dapan~enzof Fishsies and the Em-i~onment.Fisher& and Màrine Service fndustry Reports. The current ysies name kas chmgel ~ithreport number 111. lndwsrr! reports are produc& rqiortdk bur are numkred nationrtlty. Requests .for indi\ idual rqporfs w il1 be fifkd by the issuing~rqblishmentl~tcdon the front cûvw and title page. Out-of-stwk feports-will k svpplied for fw? b'J; commacia~agents. Les rapporis 4 1'indlasrrk am t knmf k résultats des acîivitis de mher&c et de diveloppern-enl qui peuvent &se utiles a I'industrie gour des applications immédiates ou fatures. -

Revista Completa En

Comercio mayorista de productos pesqueros Consumo de pescado en conserva Logística de grandes volúmenes Mejora de la protección de los consumidores y usuarios Comisiones por el uso de tarjetas de pago ICAN ^^ INSTITUTO DE CALIDAD AGROALIMENTARIA DE NAVARRA DISTINGUIMOS LA CALIDAD SEAN CUALES SEAN TUS GUSTOS, LOS PRODUCTOS NAVARROS TE CONVENCERÁN POR SU SABOR. , ^ f ^ ,, ^,, ^ ^ ^ f tiL Comercialización mayorista de productos pesqueros en España La posición de la Red de Mercas y del resto de canales José Ma Marcos Pujol y Pau Sansa Brinquis Análisis de las principales especies pesqueras comercializadas (111) José Luis Illescas, Olga Bacho y Susana Ferrer 24 Mejora de la protección de los consumidores y usuarios . , Mejillón 34 Análisis de los cambios •. Chirla y almejas 42 introducidos por la nueva ^•..• Pulpo 52 Calamar, calamar europeo Ley 44/2006 ..•. •^.• 1 . .^ • s• . Víctor Manteca Valdelande 122 .^ y chipirón 60 . ° :. _. •-a • . Choco, jibia o sepia 66 . •^ . ; ^• ^ ... Comisiones por el uso de . ^... .. Otros bivalvos 72 . ,^.^ . tarjetas de pago r.r.-e ^^..•••.. •. Análisis del consumo Pedro M. Pascual Femández 132 . .- .• •^ . de pescado en conserva ^ Víctor J. Martín Cerdeño 80 Alimentos de España 1 . Navarra 139 .•1 ^ . ., •• . De vides, vinos, vidueños ., . ,. , y planes estratégicos Distribución y Consumo inicia en este número , , Emilio Barco . 1 . una nueva sección, • _. : ._ ^. _ • bajo el título genérico de Alimentos de . ^^ La guerra de las temperaturas España, que analizará • ^I• , •, ^ Silvia Andrés González-Moralejo 109 la realidad alimentaria de todas las Logística de grandes volúmenes comunidades Sylvia Resa 116 autónomas. ^c.]uGLeLL°l ^ : .. .............................................. : 1 • ^^ . ^^ , ^ . Novedades legislativas 164 Notas de prensa /Noticias 166 . .. :^ :^. ^^•^ Mercados/Literaturas Irina '91SNi:I17P[K.77 :7Ti^?I^^l ^T-^^7 .^.1^.^ Lourdes Borrás Reyes :•^^^;;^ i^.^..i^l^:.^=. -

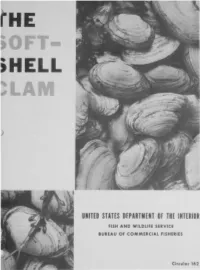

Circular 162. the Soft-Shell Clam

HE OFT iHELL 'LAM UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT 8F THE INTERIOR FISH AND WILDLIFE SERVICE BUREAU OF COMMERCIAL FISHERIES Circular 162 CONTENTS Page 1 Intr oduc tion. • • • . 2 Natural history • . ~ . 2 Distribution. 3 Taxonomy. · . Anatomy. • • • •• . · . 3 4 Life cycle. • • • • • . • •• Predators, diseases, and parasites . 7 Fishery - methods and management .•••.••• • 9 New England area. • • • • • . • • • • • . .. 9 Chesapeake area . ........... 1 1 Special problem s of paralytic shellfish poisoning and pollution . .............. 13 Summary . .... 14 Acknowledgment s •••• · . 14 Selected bibliography •••••• 15 ABSTRACT Describes the soft- shell cla.1n industry of the Atlantic coast; reviewing past and present economic importance, fishery methods, fishery management programs, and special problems associated with shellfish culture and marketing. Provides a summary of soft- shell clam natural history in- eluding distribution, taxonomy, anatomy, and life cycle. l THE SOFT -SHELL CLAM by Robert W. Hanks Bureau of Commercial Fisheries Biological Labor ator y U.S. Fish and Wildlife Serv i c e Boothbay Harbor, Maine INTRODUCTION for s a lted c l a m s used as bait by cod fishermen on t he G r and Bank. For the next The soft-shell clam, Myaarenaria L., has 2 5 years this was the most important outlet played an important role in the history and for cla ms a nd was a sour ce of wealth to economy of the eastern coast of our country . some coastal communities . Many of the Long before the first explorers reached digg ers e a rne d up t o $10 per day in this our shores, clams were important in the busin ess during October to March, when diet of some American Indian tribes. -

Marine Ecology Progress Series 502:219

The following supplement accompanies the article Spatial patterns in early post-settlement processes of the green sea urchin Strongylocentrotus droebachiensis L. B. Jennings*, H. L. Hunt Department of Biology, University of New Brunswick, PO Box 5050, Saint John, New Brunswick E2L 4L5, Canada *Corresponding author: [email protected] Marine Ecology Progress Series 502: 219–228 (2014) Supplement. Table S1. Average abundance of organisms in the cages for the with-suite treatments at the end of the experiment at the 6 sites in 2008 Birch Dick’s Minister’s Tongue Midjic Clark’s Cove Island Island Shoal Bluff Point Amphipod Corophium 38.5 37.5 21.5 21.6 52.1 40.7 Amphipod Gammaridean 1.4 1.8 3.8 16.2 19.8 16.4 Amphipod sp. 0.5 0.4 0.0 0.0 0.1 0.0 Amphiporus angulatus 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.2 0.1 Amphitrite cirrata 0.0 0.0 0.1 0.0 0.0 0.0 Amphitrite ornata 0.1 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 Anenome sp. 1 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.4 0.3 0.0 Anenome sp. 2 0.0 0.1 0.3 0.0 0.0 3.7 Anomia simplex 47.6 28.7 25.2 25.2 10.3 10.4 Anomia squamula 3.2 1.6 0.8 1.1 0.1 0.2 Arabellid unknown 0.0 0.1 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.1 Ascidian sp. 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.1 0.0 0.0 Astarte sp. -

Bankia Setacea Class: Bivalvia, Heterodonta, Euheterodonta

Phylum: Mollusca Bankia setacea Class: Bivalvia, Heterodonta, Euheterodonta Order: Imparidentia, Myida The northwest or feathery shipworm Family: Pholadoidea, Teredinidae, Bankiinae Taxonomy: The original binomen for Bankia the presence of long siphons. Members of setacea was Xylotrya setacea, described by the family Teredinidae are modified for and Tryon in 1863 (Turner 1966). William Leach distiguished by a wood-boring mode of life described several molluscan genera, includ- (Sipe et al. 2000), pallets at the siphon tips ing Xylotrya, but how his descriptions were (see Plate 394C, Coan and Valentich-Scott interpreted varied. Although Menke be- 2007) and distinct anterior shell indentation. lieved Xylotrya to be a member of the Phola- They are commonly called shipworms (though didae, Gray understood it as a member of they are not worms at all!) and bore into many the Terdinidae and synonyimized it with the wooden structures. The common name ship- genus Bankia, a genus designated by the worm is based on their vermiform morphology latter author in 1842. Most authors refer to and a shell that only covers the anterior body Bankia setacea (e.g. Kozloff 1993; Sipe et (Ricketts and Calvin 1952; see images in al. 2000; Coan and Valentich-Scott 2007; Turner 1966). Betcher et al. 2012; Borges et al. 2012; Da- Body: Bizarrely modified bivalve with re- vidson and de Rivera 2012), although one duced, sub-globular body. For internal anato- recent paper sites Xylotrya setacea (Siddall my, see Fig. 1, Canadian…; Fig. 1 Betcher et et al. 2009). Two additional known syno- al. 2012. nyms exist currently, including Bankia Color: osumiensis, B. -

The Effects of Environment on Arctica Islandica Shell Formation and Architecture

Biogeosciences, 14, 1577–1591, 2017 www.biogeosciences.net/14/1577/2017/ doi:10.5194/bg-14-1577-2017 © Author(s) 2017. CC Attribution 3.0 License. The effects of environment on Arctica islandica shell formation and architecture Stefania Milano1, Gernot Nehrke2, Alan D. Wanamaker Jr.3, Irene Ballesta-Artero4,5, Thomas Brey2, and Bernd R. Schöne1 1Institute of Geosciences, University of Mainz, Joh.-J.-Becherweg 21, 55128 Mainz, Germany 2Alfred Wegener Institute for Polar and Marine Research, Am Handelshafen 12, 27570 Bremerhaven, Germany 3Department of Geological and Atmospheric Sciences, Iowa State University, Ames, Iowa 50011-3212, USA 4Royal Netherlands Institute for Sea Research and Utrecht University, P.O. Box 59, 1790 AB Den Burg, Texel, the Netherlands 5Department of Animal Ecology, VU University Amsterdam, Amsterdam, the Netherlands Correspondence to: Stefania Milano ([email protected]) Received: 27 October 2016 – Discussion started: 7 December 2016 Revised: 1 March 2017 – Accepted: 4 March 2017 – Published: 27 March 2017 Abstract. Mollusks record valuable information in their hard tribution, and (2) scanning electron microscopy (SEM) was parts that reflect ambient environmental conditions. For this used to detect changes in microstructural organization. Our reason, shells can serve as excellent archives to reconstruct results indicate that A. islandica microstructure is not sen- past climate and environmental variability. However, animal sitive to changes in the food source and, likely, shell pig- physiology and biomineralization, which are often poorly un- ment are not altered by diet. However, seawater temperature derstood, can make the decoding of environmental signals had a statistically significant effect on the orientation of the a challenging task. -

The Malacological Society of London

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This meeting was made possible due to generous contributions from the following individuals and organizations: Unitas Malacologica The program committee: The American Malacological Society Lynn Bonomo, Samantha Donohoo, The Western Society of Malacologists Kelly Larkin, Emily Otstott, Lisa Paggeot David and Dixie Lindberg California Academy of Sciences Andrew Jepsen, Nick Colin The Company of Biologists. Robert Sussman, Allan Tina The American Genetics Association. Meg Burke, Katherine Piatek The Malacological Society of London The organizing committee: Pat Krug, David Lindberg, Julia Sigwart and Ellen Strong THE MALACOLOGICAL SOCIETY OF LONDON 1 SCHEDULE SUNDAY 11 AUGUST, 2019 (Asilomar Conference Center, Pacific Grove, CA) 2:00-6:00 pm Registration - Merrill Hall 10:30 am-12:00 pm Unitas Malacologica Council Meeting - Merrill Hall 1:30-3:30 pm Western Society of Malacologists Council Meeting Merrill Hall 3:30-5:30 American Malacological Society Council Meeting Merrill Hall MONDAY 12 AUGUST, 2019 (Asilomar Conference Center, Pacific Grove, CA) 7:30-8:30 am Breakfast - Crocker Dining Hall 8:30-11:30 Registration - Merrill Hall 8:30 am Welcome and Opening Session –Terry Gosliner - Merrill Hall Plenary Session: The Future of Molluscan Research - Merrill Hall 9:00 am - Genomics and the Future of Tropical Marine Ecosystems - Mónica Medina, Pennsylvania State University 9:45 am - Our New Understanding of Dead-shell Assemblages: A Powerful Tool for Deciphering Human Impacts - Sue Kidwell, University of Chicago 2 10:30-10:45 -

Diarrhetic Shellfish Toxins and Other Lipophilic Toxins of Human Health Concern in Washington State

Mar. Drugs 2013, 11, 1-x manuscripts; doi:10.3390/md110x000x OPEN ACCESS Marine Drugs ISSN 1660-3397 www.mdpi.com/journal/marinedrugs Article Diarrhetic Shellfish Toxins and Other Lipophilic Toxins of Human Health Concern in Washington State Vera L. Trainer 1,*, Leslie Moore 1, Brian D. Bill 1, Nicolaus G. Adams 1, Neil Harrington 2, Jerry Borchert 3, Denis A.M. da Silva 1 and Bich-Thuy L. Eberhart 1 1 Marine Biotoxins Program, Environmental Conservation Division, Northwest Fisheries Science Center, National Marine Fisheries Service, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, 2725 Montlake Blvd. E, Seattle, WA 98112, USA; E-Mails: [email protected] (L.M.); [email protected] (B.D.B.); [email protected] (N.G.A.); [email protected] (D.A.M.D.S.); [email protected] (B.-T.L.E.) 2 Jamestown S’Klallam Tribe, 1033 Old Blyn Highway, Sequim, WA 98392, USA; E-Mail: [email protected] 3 Office of Shellfish and Water Protection, Washington State Department of Health, 111 Israel Rd SE, Tumwater, WA 98504, USA; E-Mail: [email protected] * Author to whom correspondence should be addressed; E-Mail: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-206-860-6788; Fax: +1-206-860-3335. Received: 13 March 2013; in revised form: 7 April 2013 / Accepted: 23 April 2013 / Published: Abstract: The illness of three people in 2011 after their ingestion of mussels collected from Sequim Bay State Park, Washington State, USA, demonstrated the need to monitor diarrhetic shellfish toxins (DSTs) in Washington State for the protection of human health.