Role for E2F in DNA Damage-Induced Entry of Cells Into S Phase1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DNA Damage Checkpoint Dynamics Drive Cell Cycle Phase Transitions

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/137307; this version posted August 4, 2017. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY 4.0 International license. DNA damage checkpoint dynamics drive cell cycle phase transitions Hui Xiao Chao1,2, Cere E. Poovey1, Ashley A. Privette1, Gavin D. Grant3,4, Hui Yan Chao1, Jeanette G. Cook3,4, and Jeremy E. Purvis1,2,4,† 1Department of Genetics 2Curriculum for Bioinformatics and Computational Biology 3Department of Biochemistry and Biophysics 4Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill 120 Mason Farm Road Chapel Hill, NC 27599-7264 †Corresponding Author: Jeremy Purvis Genetic Medicine Building 5061, CB#7264 120 Mason Farm Road Chapel Hill, NC 27599-7264 [email protected] ABSTRACT DNA damage checkpoints are cellular mechanisms that protect the integrity of the genome during cell cycle progression. In response to genotoxic stress, these checkpoints halt cell cycle progression until the damage is repaired, allowing cells enough time to recover from damage before resuming normal proliferation. Here, we investigate the temporal dynamics of DNA damage checkpoints in individual proliferating cells by observing cell cycle phase transitions following acute DNA damage. We find that in gap phases (G1 and G2), DNA damage triggers an abrupt halt to cell cycle progression in which the duration of arrest correlates with the severity of damage. However, cells that have already progressed beyond a proposed “commitment point” within a given cell cycle phase readily transition to the next phase, revealing a relaxation of checkpoint stringency during later stages of certain cell cycle phases. -

Mitosis Vs. Meiosis

Mitosis vs. Meiosis In order for organisms to continue growing and/or replace cells that are dead or beyond repair, cells must replicate, or make identical copies of themselves. In order to do this and maintain the proper number of chromosomes, the cells of eukaryotes must undergo mitosis to divide up their DNA. The dividing of the DNA ensures that both the “old” cell (parent cell) and the “new” cells (daughter cells) have the same genetic makeup and both will be diploid, or containing the same number of chromosomes as the parent cell. For reproduction of an organism to occur, the original parent cell will undergo Meiosis to create 4 new daughter cells with a slightly different genetic makeup in order to ensure genetic diversity when fertilization occurs. The four daughter cells will be haploid, or containing half the number of chromosomes as the parent cell. The difference between the two processes is that mitosis occurs in non-reproductive cells, or somatic cells, and meiosis occurs in the cells that participate in sexual reproduction, or germ cells. The Somatic Cell Cycle (Mitosis) The somatic cell cycle consists of 3 phases: interphase, m phase, and cytokinesis. 1. Interphase: Interphase is considered the non-dividing phase of the cell cycle. It is not a part of the actual process of mitosis, but it readies the cell for mitosis. It is made up of 3 sub-phases: • G1 Phase: In G1, the cell is growing. In most organisms, the majority of the cell’s life span is spent in G1. • S Phase: In each human somatic cell, there are 23 pairs of chromosomes; one chromosome comes from the mother and one comes from the father. -

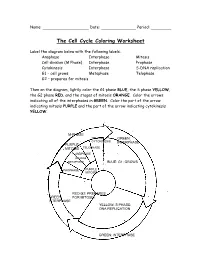

The Cell Cycle Coloring Worksheet

Name: Date: Period: The Cell Cycle Coloring Worksheet Label the diagram below with the following labels: Anaphase Interphase Mitosis Cell division (M Phase) Interphase Prophase Cytokinesis Interphase S-DNA replication G1 – cell grows Metaphase Telophase G2 – prepares for mitosis Then on the diagram, lightly color the G1 phase BLUE, the S phase YELLOW, the G2 phase RED, and the stages of mitosis ORANGE. Color the arrows indicating all of the interphases in GREEN. Color the part of the arrow indicating mitosis PURPLE and the part of the arrow indicating cytokinesis YELLOW. M-PHASE YELLOW: GREEN: CYTOKINESIS INTERPHASE PURPLE: TELOPHASE MITOSIS ANAPHASE ORANGE METAPHASE BLUE: G1: GROWS PROPHASE PURPLE MITOSIS RED:G2: PREPARES GREEN: FOR MITOSIS INTERPHASE YELLOW: S PHASE: DNA REPLICATION GREEN: INTERPHASE Use the diagram and your notes to answer the following questions. 1. What is a series of events that cells go through as they grow and divide? CELL CYCLE 2. What is the longest stage of the cell cycle called? INTERPHASE 3. During what stage does the G1, S, and G2 phases happen? INTERPHASE 4. During what phase of the cell cycle does mitosis and cytokinesis occur? M-PHASE 5. During what phase of the cell cycle does cell division occur? MITOSIS 6. During what phase of the cell cycle is DNA replicated? S-PHASE 7. During what phase of the cell cycle does the cell grow? G1,G2 8. During what phase of the cell cycle does the cell prepare for mitosis? G2 9. How many stages are there in mitosis? 4 10. Put the following stages of mitosis in order: anaphase, prophase, metaphase, and telophase. -

Working on Genomic Stability: from the S-Phase to Mitosis

G C A T T A C G G C A T genes Review Working on Genomic Stability: From the S-Phase to Mitosis Sara Ovejero 1,2,3,* , Avelino Bueno 1,4 and María P. Sacristán 1,4,* 1 Instituto de Biología Molecular y Celular del Cáncer (IBMCC), Universidad de Salamanca-CSIC, Campus Miguel de Unamuno, 37007 Salamanca, Spain; [email protected] 2 Institute of Human Genetics, CNRS, University of Montpellier, 34000 Montpellier, France 3 Department of Biological Hematology, CHU Montpellier, 34295 Montpellier, France 4 Departamento de Microbiología y Genética, Universidad de Salamanca, Campus Miguel de Unamuno, 37007 Salamanca, Spain * Correspondence: [email protected] (S.O.); [email protected] (M.P.S.); Tel.: +34-923-294808 (M.P.S.) Received: 31 January 2020; Accepted: 18 February 2020; Published: 20 February 2020 Abstract: Fidelity in chromosome duplication and segregation is indispensable for maintaining genomic stability and the perpetuation of life. Challenges to genome integrity jeopardize cell survival and are at the root of different types of pathologies, such as cancer. The following three main sources of genomic instability exist: DNA damage, replicative stress, and chromosome segregation defects. In response to these challenges, eukaryotic cells have evolved control mechanisms, also known as checkpoint systems, which sense under-replicated or damaged DNA and activate specialized DNA repair machineries. Cells make use of these checkpoints throughout interphase to shield genome integrity before mitosis. Later on, when the cells enter into mitosis, the spindle assembly checkpoint (SAC) is activated and remains active until the chromosomes are properly attached to the spindle apparatus to ensure an equal segregation among daughter cells. -

S-Phase Entry, Activation of E2F-Responsive Genes, and Apoptosis

Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA Vol. 92, pp. 5436-5440, June 1995 Medical Sciences Deficiency of retinoblastoma protein leads to inappropriate S-phase entry, activation of E2F-responsive genes, and apoptosis (tumor supressor gene/cell cycle control/programmed cell death) ALEXANDRU ALMASAN*tt, YUXIN YIN*t§, RUTH E. KELLY*, EVA Y.-H. P. LEES, ALLAN BRADLEYII, WEIWEI LI**, JOSEPH R. BERTINO**, AND GEOFFREY M. WAHL*tt *Gene Expression Laboratory, The Salk Institute, 10010 North Torrey Pines Road, La Jolla, CA 92037; tCenter for Molecular Medicine and Institute of Biotechnology, The University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, San Antonio, TX 78284; I'Department of Molecular and Human Genetics and Howard Hughes Medical Institute, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX 77030; and **Program for Molecular Pharmacology and Therapeutics, Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, New York, NY 10021 Communicated by Leslie E. Orgel, The Salk Institute for Biological Studies, San Diego, CA, January 24, 1995 (received for review December 12, 1994) ABSTRACT The retinoblastoma susceptibility gene (Rb) thymidylate synthase (TS) and other genes necessary for entry participates in controlling the G1/S-phase transition, pre- into and progression through S phase (10, 14). sumably by binding and inactivating E2F transcription acti- The data obtained from studies with viral oncoproteins vator family members. Mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) suggest that Rb protein acts by sequestering essential factors with no, one, or two inactivated Rb genes were used to determine required for G1/S progression. However, each of these onco- the specific contributions of Rb protein to cell cycle progres- proteins binds other cellular factors such as the Rb-related sion and gene expression. -

Regulation of the Cell Cycle and DNA Damage-Induced Checkpoint Activation

RnDSy-lu-2945 Regulation of the Cell Cycle and DNA Damage-Induced Checkpoint Activation IR UV IR Stalled Replication Forks/ BRCA1 Rad50 Long Stretches of ss-DNA Rad50 Mre11 BRCA1 Nbs1 Rad9-Rad1-Hus1 Mre11 RPA MDC1 γ-H2AX DNA Pol α/Primase RFC2-5 MDC1 Nbs1 53BP1 MCM2-7 53BP1 γ-H2AX Rad17 Claspin MCM10 Rad9-Rad1-Hus1 TopBP1 CDC45 G1/S Checkpoint Intra-S-Phase RFC2-5 ATM ATR TopBP1 Rad17 ATRIP ATM Checkpoint Claspin Chk2 Chk1 Chk2 Chk1 ATR Rad50 ATRIP Mre11 FANCD2 Ubiquitin MDM2 MDM2 Nbs1 CDC25A Rad50 Mre11 BRCA1 Ub-mediated Phosphatase p53 CDC25A Ubiquitin p53 FANCD2 Phosphatase Degradation Nbs1 p53 p53 CDK2 p21 p21 BRCA1 Ub-mediated SMC1 Degradation Cyclin E/A SMC1 CDK2 Slow S Phase CDC45 Progression p21 DNA Pol α/Primase Slow S Phase p21 Cyclin E Progression Maintenance of Inhibition of New CDC6 CDT1 CDC45 G1/S Arrest Origin Firing ORC MCM2-7 MCM2-7 Recovery of Stalled Replication Forks Inhibition of MCM10 MCM10 Replication Origin Firing DNA Pol α/Primase ORI CDC6 CDT1 MCM2-7 ORC S Phase Delay MCM2-7 MCM10 MCM10 ORI Geminin EGF EGF R GAB-1 CDC6 CDT1 ORC MCM2-7 PI 3-Kinase p70 S6K MCM2-7 S6 Protein Translation Pre-RC (G1) GAB-2 MCM10 GSK-3 TSC1/2 MCM10 ORI PIP2 TOR Promotes Replication CAK EGF Origin Firing Origin PIP3 Activation CDK2 EGF R Akt CDC25A PDK-1 Phosphatase Cyclin E/A SHIP CIP/KIP (p21, p27, p57) (Active) PLCγ PP2A (Active) PTEN CDC45 PIP2 CAK Unwinding RPA CDC7 CDK2 IP3 DAG (Active) Positive DBF4 α Feedback CDC25A DNA Pol /Primase Cyclin E Loop Phosphatase PKC ORC RAS CDK4/6 CDK2 (Active) Cyclin E MCM10 CDC45 RPA IP Receptor -

Human P14arf-Mediated Cell Cycle Arrest Strictly Depends on Intact P53 Signaling Pathways

Oncogene (2002) 21, 3207 ± 3212 ã 2002 Nature Publishing Group All rights reserved 0950 ± 9232/02 $25.00 www.nature.com/onc Human p14ARF-mediated cell cycle arrest strictly depends on intact p53 signaling pathways H Oliver Weber1,2, Temesgen Samuel1,3, Pia Rauch1 and Jens Oliver Funk*,1 1Laboratory of Molecular Tumor Biology, Department of Dermatology, University of Erlangen-Nuremberg, 91052 Erlangen, Germany; 2Regulation of Cell Growth Laboratory, National Cancer Institute, Frederick, Maryland, MD 21702-1201, USA The tumor suppressor ARF is transcribed from the INK4a/ 4 and 6 activities, thus leading to decreased phosphor- ARF locus in partly overlapping reading frames with the ylation of RB and to G1 arrest. Cells that are de®cient CDK inhibitor p16Ink4a. ARF is able to antagonize the for RB are resistant to p16Ink4a-mediated cell cycle MDM2-mediated ubiquitination and degradation of p53, arrest (Sherr and Roberts, 1995; Weinberg, 1995). leading to either cell cycle arrest or apoptosis, depending on ARF is also a cell cyle inhibitor. It does not directly the cellular context. However, recent data point to inhibit CDKs but interferes with the function of additional p53-independent functions of mouse p19ARF. MDM2 to destabilize p53. ARF may be activated by Little is known about the dependency of human p14ARF aberrant activation of oncoproteins such as Ras function on p53 and its downstream genes. Therefore, we (Palmero et al., 1998), c-myc (Zindy et al., 1998), analysed the mechanism of p14ARF-induced cell cycle arrest E1A (de Stanchina et al., 1998), Abl (Radfar et al., in several human cell types. -

P14arf Expression Increases Dihydrofolate Reductase Degradation and Paradoxically Results in Resistance to Folate Antagonists in Cells with Nonfunctional P53

[CANCER RESEARCH 64, 4338–4345, June 15, 2004] p14ARF Expression Increases Dihydrofolate Reductase Degradation and Paradoxically Results in Resistance to Folate Antagonists in Cells with Nonfunctional p53 Pellegrino G. Magro,1,2 Angelo J. Russo,1,2 Wei-Wei Li,2 Debabrata Banerjee,3 and Joseph R. Bertino3 1Joan and Sanford I. Weill Graduate School of Medical Sciences of Cornell University, New York, New York; 2Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, New York; and 3The Cancer Institute of New Jersey, Robert Wood Johnson Medical School, New Brunswick, New Jersey ABSTRACT Although much is known about the function of ARF in the p53 pathway, less is known about its functions in human tumor growth and ARF The p14 protein, the product of an alternate reading frame of the chemosensitivity independently of its regulation of p53 via binding to INK4A/ARF locus on human chromosome 9p21, disrupts the ability of MDM2. Mouse embryonic fibroblasts expressing E1A and exogenous MDM2 to target p53 for proteosomal degradation and causes an increase ARF are more sensitive to killing by doxorubicin than their normal in steady-state p53 levels, leading to a G1 and G2 arrest of cells in the cell cycle. Although much is known about the function of p14ARF in the p53 counterparts that only express E1A (7). Alterations in the INK4A/ pathway, not as much is known about its function in human tumor growth ARF locus reduce p53 induction and cytotoxicity of cyclophospha- and chemosensitivity independently of up-regulation of p53 protein levels. mide in mouse lymphomas (16). Also, recombinant adenovirus-me- To learn more about its effect on cellular proliferation and chemoresis- diated p14ARF overexpression sensitizes MCF-7 breast cancer cells to tance independent of p53 up-regulation, human HT-1080 fibrosarcoma cisplatin (17). -

Cyclin-Dependent Kinase 7 (CDK7) Expression in Human Hepatocellular Carcinoma: Association with HCC Progression, Prognosis and Cell Proliferative Capacity

479 Original Article Cyclin-dependent kinase 7 (CDK7) expression in human hepatocellular carcinoma: association with HCC progression, prognosis and cell proliferative capacity Zheran Liu1,2#, Dajiao Liu1#, Rongrong Zhong2, Qiuyun Su1, Tiancheng Zhao3, Fen Fu4, Jinsheng Liu5, Derong Xu1, Changqing Zeng5 1School of Public Health, Nanchang University, Nanchang 330031, China; 2Queen Mary School, Medical College of Nanchang University, Nanchang 330031, China; 3The School of General Studies, Columbia University in the City of New York, New York, NY, USA; 4The Second Affiliated Hospital of Nanchang University, Nanchang 330031, China; 5Provincial College of Clinical Medicine, Fujian Provincial Hospital of Fujian Medical University, Fuzhou 350001, China Contributions: (I) Conception and design: D Xu; (II) Administrative support: C Zeng; (III) Provision of study materials or patients: D Liu; (IV) Collection and assembly of data: Z Liu; (V) Data analysis and interpretation: Z Liu; (VI) Manuscript writing: All authors; (VII) Final approval of manuscript: All authors. #These authors contributed equally to this work. Correspondence to: Derong Xu. School of Public Health, Nanchang University, Nanchang 330031, China. Email: [email protected]; Changqing Zeng. Provincial College of Clinical Medicine, Fujian Provincial Hospital of Fujian Medical University, Fuzhou 350001, China. Email: [email protected]. Background: Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is one of the most common malignancies in the world and contributes to a high cancer mortality globally. The multistep progression of HCC is highly related to the activation of oncogenes and the deactivation of cancer suppressor genes. The cyclin-dependent kinase 7 (CDK7) gene is responsible for maintaining a normal cell cycle, acting as a gatekeeper, and plays an important part in RNA transcription. -

CDK Regulation of Meiosis: Lessons from S. Cerevisiae and S. Pombe

G C A T T A C G G C A T genes Review CDK Regulation of Meiosis: Lessons from S. cerevisiae and S. pombe Anne M. MacKenzie and Soni Lacefield * Department of Biology, Indiana University, 1001 E. Third Street, Bloomington, IN 47405, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-812-856-2429 Received: 16 May 2020; Accepted: 26 June 2020; Published: 29 June 2020 Abstract: Meiotic progression requires precise orchestration, such that one round of DNA replication is followed by two meiotic divisions. The order and timing of meiotic events is controlled through the modulation of the phosphorylation state of proteins. Key components of this phospho-regulatory system include cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) and its cyclin regulatory subunits. Over the past two decades, studies in budding and fission yeast have greatly informed our understanding of the role of CDK in meiotic regulation. In this review, we provide an overview of how CDK controls meiotic events in both budding and fission yeast. We discuss mechanisms of CDK regulation through post-translational modifications and changes in the levels of cyclins. Finally, we highlight the similarities and differences in CDK regulation between the two yeast species. Since CDK and many meiotic regulators are highly conserved, the findings in budding and fission yeasts have revealed conserved mechanisms of meiotic regulation among eukaryotes. Keywords: meiosis; Cyclin-Dependent Kinase; CDK; cyclin; APC/C; budding yeast; fission yeast; chromosome segregation 1. Introduction Control of the eukaryotic cell cycle occurs through the modulation of phosphorylation states of proteins that trigger specific events. At the forefront of this phospho-regulation are the cyclin-dependent kinases (CDKs), whose oscillatory activity results in a large number of phosphorylations that change the activation state of their substrates [1,2]. -

Mitosis and Meiosis

BIOLOGY 100 SOLUTIONS TO PROBLEMS MITOSIS AND MEIOSIS 1. If an organism has 15 pairs of homologous chromosomes, how many chromosomes will each daughter cell have after telophase of mitosis? In this same organism, how many chromosomes will each daughter cell have after telophase II of meiosis? n 2n n 2n 2n 2n n n Mitosis Meiosis If a cell has 15 pairs of chromosomes (n = 15), it has 30 chromosomes (2n = 30). At the end of mitosis, the two daughter cells will be exact copies of the original cell. Each daughter cell will have 30 chromosomes. At the end of meiosis II, each cell (i.e., gamete) would have half the original number of chromosomes, that is, 15 chromosomes. 2. How many DNA molecules are present in a chromosome of a cell in metaphase of mitosis? How many DNA molecules are present in a chromosome of a cell at metaphase II of meiosis? A chromosome in G1 of the cell cycle is composed of a very long molecule of double stranded DNA. Recall that DNA is replicated during the S phase of the cell cycle. Thus during metaphase of mitosis, each chromosome (i.e., each chromatid pair) will contain two molecules of double stranded DNA (one molecule per sister chromatid). The following diagram depicts the behavior of one homologous pair of chromosomes during mitosis. In a real cell, chromosomes would not be visible during interphase of the cell cycle. S phase mitosis telophase of mitosis During prophase I and metaphase I of meiosis, a chromosome consists of a tetrad (4 chromatids or 4 DNA molecules) and is reduced to two chromatids (2 DNA molecules) by the time metaphase II occurs. -

RB and Cell Cycle Progression

Oncogene (2006) 25, 5220–5227 & 2006 Nature Publishing Group All rights reserved 0950-9232/06 $30.00 www.nature.com/onc REVIEW RB and cell cycle progression C Giacinti1,2 and A Giordano1,2 1Sbarro Institute for Cancer Research and Molecular Medicine, Temple University, Philadelphia, PA, USA and 2Department of Human Pathology and Oncology, University of Siena, Siena, Italy The Rb protein is a tumor suppressor, which plays a of a tumor suppressor. Several human tumors show pivotal role in the negative control of the cell cycle and in mutations and deletions of the Rb gene, and inherited tumor progression. It has been shown that Rb protein allelic loss of Rb confers increased susceptibility to (pRb)is responsible for a major G1 checkpoint, blocking cancer formation (Dunn et al., 1988). The Rb gene is S-phase entry and cell growth. The retinoblastoma family functionally inactivated in most human neoplasms includes three members, Rb/p105, p107 and Rb2/p130, either by direct mutation/deletion, such as in retino- collectively referred to as ‘pocket proteins’. The pRb blastoma, osteosarcoma and small-cell lung carcinoma, protein represses gene transcription, required for transi- or indirectly through altered expression/activity of tion from G1 to S phase, by directly binding to the upstream regulators (Liu et al., 2004). Nevertheless, transactivation domain of E2F and by binding to the the Rb protein plays a pivotal role in the negative promoter of these genes as a complex with E2F. pRb control of the cell cycle and in tumor progression. represses transcription also by remodeling chromatin It has been shown that Rb protein (pRb) is structure through interaction with proteins such as responsible for a major G1 checkpoint (restriction hBRM, BRG1, HDAC1 and SUV39H1, which are point) blocking S-phase entry and cell growth, promot- involved in nucleosome remodeling, histone acetylation/ ing terminal differentiation by inducing both cell cycle deacetylation and methylation, respectively.