Pterostylis Squamata

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pterostylis Curta Blunt Greenhood

PLANT Pterostylis curta Blunt Greenhood AUS SA AMLR Endemism Life History RP, Myponga, Victor Harbor, Anstey Hill, Willunga, Ashbourne, Mount Barker and near Mount Bold - R V - Perennial Reservoir.5 Family ORCHIDACEAE Habitat Forms small to extensive colonies in fertile loams in deeply shaded gullies and along creeks in high rainfall areas.4 Occurs in sclerophyll forest, growing in slightly moist conditions.2 In the AMLR, recorded habitat includes: Cherry Gardens area, under Eucalyptus viminalis in grassy area, with Pterostylis nutans and P. pedunculata Onkaparinga River, near bottom of gorge in rocky damp places; Mount Bold (Thomas Gully) Wotton’s Scrub (Kenneth Stirling CP) (K. Brewer and J. Smith pers. comm.) Second Valley area on stream bank under heavy canopy of Pinus radiata.7 Photo: © Peter Lang Within the AMLR the preferred broad vegetation Conservation Significance groups are Grassy woodland and Riparian.5 The AMLR distribution is disjunct, isolated from other extant occurrences within SA. Within the AMLR the Within the AMLR the species’ degree of habitat species’ relative area of occupancy is classified as specialisation is classified as ‘High’.5 ‘Very Restricted’.5 Biology and Ecology Description Flowers from July to October.3,4 Terrestrial orchid; slender, glabrous, 10-20 cm high; leaves on rather long petioles in a radical rosette.4 All known pollinators of the genus Pterostylis are male Flower stem to 30 cm tall. Flower usually single, the insects of the fungus gnat and mosquito family.2 galea about 3 cm high, erect, green with pale brown Pterostylis curta will hybridise with P. pedunculata and tints.3 P. -

Pollination and Evolution of Plant and Insect Interaction JPP 2017; 6(3): 304-311 Received: 03-03-2017 Accepted: 04-04-2017 Showket a Dar, Gh

Journal of Pharmacognosy and Phytochemistry 2017; 6(3): 304-311 E-ISSN: 2278-4136 P-ISSN: 2349-8234 Pollination and evolution of plant and insect interaction JPP 2017; 6(3): 304-311 Received: 03-03-2017 Accepted: 04-04-2017 Showket A Dar, Gh. I Hassan, Bilal A Padder, Ab R Wani and Sajad H Showket A Dar Parey Sher-e-Kashmir University of Agricultural Science and Technology, Shalimar, Jammu Abstract and Kashmir-India Flowers exploit insects to achieve pollination; at the same time insects exploit flowers for food. Insects and flowers are a partnership. Each insect group has evolved different sets of mouthparts to exploit the Gh. I Hassan food that flowers provide. From the insects' point of view collecting nectar or pollen is rather like fitting Sher-e-Kashmir University of a key into a lock; the mouthparts of each species can only exploit flowers of a certain size and shape. Agricultural Science and This is why, to support insect diversity in our gardens, we need to plant a diversity of suitable flowers. It Technology, Shalimar, Jammu is definitely not a case of 'one size fits all'. While some insects are generalists and can exploit a wide and Kashmir-India range of flowers, others are specialists and are quite particular in their needs. In flowering plants, pollen grains germinate to form pollen tubes that transport male gametes (sperm cells) to the egg cell in the Bilal A Padder embryo sac during sexual reproduction. Pollen tube biology is complex, presenting parallels with axon Sher-e-Kashmir University of guidance and moving cell systems in animals. -

Phylogenetic Relationships of Discyphus Scopulariae

Phytotaxa 173 (2): 127–139 ISSN 1179-3155 (print edition) www.mapress.com/phytotaxa/ PHYTOTAXA Copyright © 2014 Magnolia Press Article ISSN 1179-3163 (online edition) http://dx.doi.org/10.11646/phytotaxa.173.2.3 Phylogenetic relationships of Discyphus scopulariae (Orchidaceae, Cranichideae) inferred from plastid and nuclear DNA sequences: evidence supporting recognition of a new subtribe, Discyphinae GERARDO A. SALAZAR1, CÁSSIO VAN DEN BERG2 & ALEX POPOVKIN3 1Departamento de Botánica, Instituto de Biología, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Apartado Postal 70-367, 04510 México, Distrito Federal, México; E-mail: [email protected] 2Universidade Estadual de Feira de Santana, Departamento de Ciências Biológicas, Av. Transnordestina s.n., 44036-900, Feira de Santana, Bahia, Brazil 3Fazenda Rio do Negro, Entre Rios, Bahia, Brazil Abstract The monospecific genus Discyphus, previously considered a member of Spiranthinae (Orchidoideae: Cranichideae), displays both vegetative and floral morphological peculiarities that are out of place in that subtribe. These include a single, sessile, cordate leaf that clasps the base of the inflorescence and lies flat on the substrate, petals that are long-decurrent on the column, labellum margins free from sides of the column and a column provided with two separate, cup-shaped stigmatic areas. Because of its morphological uniqueness, the phylogenetic relationships of Discyphus have been considered obscure. In this study, we analyse nucleotide sequences of plastid and nuclear DNA under maximum parsimony -

Name Authority, Common Name

THREATENED SPECIES LISTING STATEMENT ORCHID Midland greenhood Pterostylis commutata D. L. Jones 1994 Status Tasmanian Threatened Species Protection Act 1995 ……………………………….……..………..………..….….endangered Commonwealth Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999……………………..…...…Critically.Endangered Hans & Annie Wapstra Description plants are 12 to 22 cm tall. They have 1 to 5 erect Midland greenhood belongs to a group of orchids shiny green flowers with translucent markings on commonly known as greenhoods because the dorsal the hood. The hood apex curves down strongly and sepal and petals are united to form a predominantly terminates with an apical point 15 to 20 mm long. green, hood-like structure that dominates the The two lateral sepals are green with dark green flower. When triggered by touch, the labellum flips lines and transparent areas. They hang down and inwards towards the column, trapping any insect are joined together leaving the 25 to 30 mm long inside the flower, thereby aiding pollination as the points free and parted by 6 to 10 mm at the tips. insect struggles to escape. Greenhoods are The labellum, which also hangs down, is dark green deciduous terrestrials that have fleshy tubers, which with a turned up tip and has an irregularly wavy are replaced annually. At some stage in their life margin with short white bristles. Two longer cycle all greenhoods produce a rosette of leaves. bristles arise from near the base. In all, the flowers are 42 to 50 mm long and 6 to 8 mm wide. The rosette of the Midland greenhood encircles the base of the flower stem. The 6 to 10 rosette leaves Midland greenhood has a distinctive flower shape are elliptical to narrowly oval shaped, 18 to 32 mm and is not easily confused with other Tasmanian long and 5 to 8 mm wide. -

FERNANDA DE SIQUEIRA PIECZAK.Pdf

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DO PARANÁ FERNANDA DE SIQUEIRA PIECZAK MICROMORFOLOGIA E ANATOMIA DA FLOR DE ESPÉCIES DE ASPIDOGYNE E MICROCHILUS (GOODYERINAE – ORCHIDACEAE) CURITIBA 2019 FERNANDA DE SIQUEIRA PIECZAK MICROMORFOLOGIA E ANATOMIA DA FLOR DE ESPÉCIES DE ASPIDOGYNE E MICROCHILUS (GOODYERINAE – ORCHIDACEAE) Dissertação apresentada ao curso de Pós-Graduação em Botânica, Área de Concentração em Morfologia e Anatomia Vegetal, Departamento de Botânica, Setor de Ciências Biológicas, Universidade Federal do Paraná, como parte das exigências para a obtenção do título de mestre em Botânica. Orientadora: Profa. Dra. Cleusa Bona Coorientador: Prof. Dr. Eric de Camargo Smidt CURITIBA 2019 Ao Albert. AGRADECIMENTOS Aos meus pais, Francisco e Reni, pelo incentivo e forças em todos os momentos. Por ser o ponto forte pelo o qual vale a pena persistir. À CAPES, pelo auxílio financeiro. Aos meus orientadores, dra. Cleusa Bona e dr. Eric de Camargo Smidt pela instrução durante esses dois anos. Aos professores do Programa de Pós-Graduação de Botânica da UFPR que contribuíram para a minha formação. Ao Mathias Engels, pelas flores concedidas de suas coletas. À Rebekah Giese e Matheus Salles agradeço imensamente pela ajuda e colaboração no desenvolvimento do trabalho. À Laura de Lannoy pelo tempo despendido para me auxiliar com equipamentos os quais precisei. Aos técnicos e colegas dos laboratórios de Botânica Estrutural e Centro de Microscopia Eletrônica da UFPR pelos conhecimentos compartilhado, tempo disponibilizado e conversas motivadoras. Ao dr. Fabiano Rodrigo da Maia, professor e amigo que sempre buscou da melhor forma advertir e transmitir um pouco do conhecimento que possui. Foi mais do que essencial para a minha construção, um exemplo que levarei para a vida. -

THE PTEROSTYLIS RUFA COMPLEX - BENTHAMS MISTAKE This Is the Text of a Talk Given Bill Kosky to the Australian Native Orchid Society (Victorian Group) on 10 May 2019

THE PTEROSTYLIS RUFA COMPLEX - BENTHAMS MISTAKE This is the text of a talk given Bill Kosky to the Australian Native Orchid Society (Victorian Group) on 10 May 2019 This talk is about somewhat similar, smaller, members of the Pterostylis rufa complex, P. rufa, P. squamata, P. aciculiformis, P. ferruginea, and P. pusilla. P. praetermissa, and other similar species from north of Sydney, are not considered here. The talk also provides insight into the rich history of Australia’s plants, and botanists, found in Australia’s Herbariam collections. Roughly the distribution of P. rufa is from north of Sydney to around Nowra; P. squamata (so called) from Nowra into the eastern half of Victoria and Tasmania; P. aciculiformis in a band across the central latitudes of Victoria into NSW and SA, with a disjunct population in East Gippsland; P. ferruginea Victoria west from the Grampians into SA; and P. pusilla in a band from central Victoria west into SA, unlike the others extending part way into the dryer northern parts of Victoria and SA. Taxonomy. The hierarchy of taxonomy can be likened to Wikipedia. That is the last valid ranking of a species takes precedence over an earlier one. Any new species named requires a type specimen (or in earlier times a specimen collection) to be nominated, and that type stands as the primary reference for that species. Bracts are modified leaves. Those that grow on and more or less embrace an orchids stem are referred to as stem bracts or sterile bracts. (In the past also as scales or empty scales, and in recent times, as stem leaves). -

Orchid Historical Biogeography, Diversification, Antarctica and The

Journal of Biogeography (J. Biogeogr.) (2016) ORIGINAL Orchid historical biogeography, ARTICLE diversification, Antarctica and the paradox of orchid dispersal Thomas J. Givnish1*, Daniel Spalink1, Mercedes Ames1, Stephanie P. Lyon1, Steven J. Hunter1, Alejandro Zuluaga1,2, Alfonso Doucette1, Giovanny Giraldo Caro1, James McDaniel1, Mark A. Clements3, Mary T. K. Arroyo4, Lorena Endara5, Ricardo Kriebel1, Norris H. Williams5 and Kenneth M. Cameron1 1Department of Botany, University of ABSTRACT Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, WI 53706, Aim Orchidaceae is the most species-rich angiosperm family and has one of USA, 2Departamento de Biologıa, the broadest distributions. Until now, the lack of a well-resolved phylogeny has Universidad del Valle, Cali, Colombia, 3Centre for Australian National Biodiversity prevented analyses of orchid historical biogeography. In this study, we use such Research, Canberra, ACT 2601, Australia, a phylogeny to estimate the geographical spread of orchids, evaluate the impor- 4Institute of Ecology and Biodiversity, tance of different regions in their diversification and assess the role of long-dis- Facultad de Ciencias, Universidad de Chile, tance dispersal (LDD) in generating orchid diversity. 5 Santiago, Chile, Department of Biology, Location Global. University of Florida, Gainesville, FL 32611, USA Methods Analyses use a phylogeny including species representing all five orchid subfamilies and almost all tribes and subtribes, calibrated against 17 angiosperm fossils. We estimated historical biogeography and assessed the -

Redalyc.ARE OUR ORCHIDS SAFE DOWN UNDER?

Lankesteriana International Journal on Orchidology ISSN: 1409-3871 [email protected] Universidad de Costa Rica Costa Rica BACKHOUSE, GARY N. ARE OUR ORCHIDS SAFE DOWN UNDER? A NATIONAL ASSESSMENT OF THREATENED ORCHIDS IN AUSTRALIA Lankesteriana International Journal on Orchidology, vol. 7, núm. 1-2, marzo, 2007, pp. 28- 43 Universidad de Costa Rica Cartago, Costa Rica Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=44339813005 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative LANKESTERIANA 7(1-2): 28-43. 2007. ARE OUR ORCHIDS SAFE DOWN UNDER? A NATIONAL ASSESSMENT OF THREATENED ORCHIDS IN AUSTRALIA GARY N. BACKHOUSE Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services Division, Department of Sustainability and Environment 8 Nicholson Street, East Melbourne, Victoria 3002 Australia [email protected] KEY WORDS:threatened orchids Australia conservation status Introduction Many orchid species are included in this list. This paper examines the listing process for threatened Australia has about 1700 species of orchids, com- orchids in Australia, compares regional and national prising about 1300 named species in about 190 gen- lists of threatened orchids, and provides recommen- era, plus at least 400 undescribed species (Jones dations for improving the process of listing regionally 2006, pers. comm.). About 1400 species (82%) are and nationally threatened orchids. geophytes, almost all deciduous, seasonal species, while 300 species (18%) are evergreen epiphytes Methods and/or lithophytes. At least 95% of this orchid flora is endemic to Australia. -

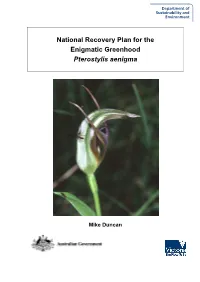

Pterostylis Aenigma

National Recovery Plan for the Enigmatic Greenhood Pterostylis aenigma Mike Duncan Prepared by Mike Duncan, Department of Sustainability and Environment, Victoria. Published by the Victorian Government Department of Sustainability and Environment (DSE) Melbourne, 2008. © State of Victoria Department of Sustainability and Environment 2008 This publication is copyright. No part may be reproduced by any process except in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. Authorised by the Victorian Government, 8 Nicholson Street, East Melbourne. ISBN 978-1-74208-713-9 This is a Recovery Plan prepared under the Commonwealth Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999, with the assistance of funding provided by the Australian Government. This Recovery Plan has been developed with the involvement and cooperation of a range of stakeholders, but individual stakeholders have not necessarily committed to undertaking specific actions. The attainment of objectives and the provision of funds may be subject to budgetary and other constraints affecting the parties involved. Proposed actions may be subject to modification over the life of the plan due to changes in knowledge. Disclaimer This publication may be of assistance to you but the State of Victoria and its employees do not guarantee that the publication is without flaw of any kind or is wholly appropriate for your particular purposes and therefore disclaims all liability for any error, loss or other consequence that may arise from you relying on any information in this publication. An electronic version of this document is available on the Department of the Environment, Water, Heritage and the Arts website www.environment.gov.au For more information contact the DSE Customer Service Centre 136 186 Citation: Duncan, M. -

Pterostylis Foliata Hook.F

NSW SCIENTIFIC COMMITTEE Preliminary Determination The Scientific Committee, established by the Threatened Species Conservation Act 1995 (the Act), has made a Preliminary Determination to support a proposal to list the terrestrial orchid Pterostylis foliata Hook.f. as a VULNERABLE SPECIES in Part 1 of Schedule 2 of the Act. Listing of Vulnerable species is provided for by Part 2 of the Act. The Scientific Committee has found that: 1. Pterostylis foliata Hook.f. (family Orchidaceae) is described as: “Terrestrial herb. Leaves 3–6, scattered on the basal part of the stem, oblong to ovate or elliptic, 2–5 cm long, 8–16 mm wide, margins crisped or wavy; sessile. Scape to 30 cm high; stem smooth. Flower c. 2 cm long, dark green and white with brown in the galea, erect. Apex of galea obliquely erect, flat or slightly decurved. Lateral sepals tightly embracing the galea; sinus broadly to deeply V-shaped when viewed from the front, protruding in a shallow curve when viewed from the side; free points linear-tapered, c. 15 mm long, erect, divergent. Petals narrow, subacute. Labellum oblong, 9–12 mm long, c. 3 mm wide, brown, obtuse, distal third protruding from the sinus in the set position.” (PlantNET, 2015). 2. There is the possibility that more than one species are included under the name Pterostylis foliata as several forms are easily recognised (Bishop 2000). Populations attributed to this species do not form a monophyletic group in the molecular phylogeny presented by Clements et al. (2011) however this study was based on a limited number of samples, none of which was from New South Wales (NSW). -

Locally Threatened Plants in Manningham

Locally Threatened Plants in Manningham Report by Dr Graeme S. Lorimer, Biosphere Pty Ltd, to Manningham City Council Version 1.0, 28 June, 2010 Executive Summary A list has been compiled containing 584 plant species that have been credibly recorded as indigenous in Manningham. 93% of these species have been assessed by international standard methods to determine whether they are threatened with extinction in Manningham. The remaining 7% of species are too difficult to assess within the scope of this project. It was found that nineteen species can be confidently presumed to be extinct in Manningham. Two hundred and forty-six species, or 42% of all indigenous species currently growing in Manningham, fall into the ‘Critically Endangered’ level of risk of extinction in the municipality. This is an indication that if current trends continue, scores of plant species could die out in Manningham over the next decade or so – far more than have become extinct since first settlement. Another 21% of species fall into the next level down on the threat scale (‘Endangered’) and 17% fall into the third (‘Vulnerable’) level. The total number of threatened species (i.e. in any of the aforementioned three levels) is 466, representing 82% of all indigenous species that are not already extinct in Manningham. These figures indicate that conservation of indigenous flora in Manningham is at a critical stage. This also has grave implications for indigenous fauna. Nevertheless, corrective measures are possible and it is still realistic to aim to maintain the existence of every indigenous plant species presently in the municipality. The scope of this study has not allowed much detail to be provided about corrective measures except in the case of protecting threatened species under the Manningham Planning Scheme. -

Pterostylis Lustra

Pterostylis lustra small sickle greenhood T A S M A N I A N T H R E A T E N E D S P E C I E S L I S T I N G S T A T E M E N T Image by Oberon Carter Scientific name: Pterostylis lustra D.L.Jones, Austral. Orchid Res. 5: 87 (2006) Common name: small sickle greenhood (Wapstra et al. 2005) Group: vascular plant, monocotyledon, family Orchidaceae Status: Threatened Species Protection Act 1995: endangered Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999: Not listed Distribution: Endemic status: not endemic to Tasmania Tasmanian NRM Regions: Cradle Coast Figure 1. Distribution of Pterostylis lustra in Tasmania, Plate 1. Inflorescence of Pterostylis lustra showing Natural Resource Management regions (image by Oberon Carter) Threatened Species Section – Department of Primary Industries, Parks, Water and Environment Listing Statement for Pterostylis lustra (small sickle greenhood) SUMMARY: Pterostylis lustra (small sickle Australia, flowering is from November and greenhood) is a terrestrial orchid that in February (Jones 2006a&b) but herbarium Tasmania is known from just 10 localities on records from Tasmania suggest a peak in the northwest coast, occurring in near-coastal Tasmania in late October to mid November swamp forest and scrub. While population data (Wapstra et al. 2012). is limited it suggests that the total population in Tasmania is small, with fewer than 250 mature The response of Pterostylis lustra to disturbance plants, and likely to occupy less than is largely undocumented but its preferred 5 ha. This makes the species susceptible to habitats have relatively low fire frequencies and inadvertent or chance events.