Voice of the Machine Sean Jackson Eads

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Popular Music and Society Artists As Entrepreneurs, Fans As Workers

This article was downloaded by: [James Madison University] On: 03 November 2014, At: 16:54 Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK Popular Music and Society Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rpms20 Artists as Entrepreneurs, Fans as Workers Jeremy Wade Morris Published online: 15 May 2013. To cite this article: Jeremy Wade Morris (2014) Artists as Entrepreneurs, Fans as Workers, Popular Music and Society, 37:3, 273-290, DOI: 10.1080/03007766.2013.778534 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/03007766.2013.778534 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Taylor & Francis makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of all the information (the “Content”) contained in the publications on our platform. However, Taylor & Francis, our agents, and our licensors make no representations or warranties whatsoever as to the accuracy, completeness, or suitability for any purpose of the Content. Any opinions and views expressed in this publication are the opinions and views of the authors, and are not the views of or endorsed by Taylor & Francis. The accuracy of the Content should not be relied upon and should be independently verified with primary sources of information. Taylor and Francis shall not be liable for any losses, actions, claims, proceedings, demands, costs, expenses, damages, and other liabilities whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with, in relation to or arising out of the use of the Content. This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. -

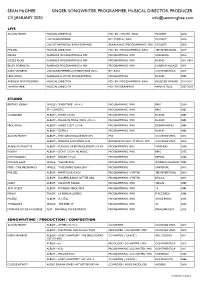

CV JANUARY 2020 [email protected]

SEAN McGHEE SINGER, SONGWRITER, PROGRAMMER, MUSICAL DIRECTOR, PRODUCER. CV JANUARY 2020 [email protected] LIVE ALISON MOYET MUSICAL DIRECTOR MD / BV / SYNTHS / BASS MODEST! 2018- LIVE BAND MEMBER BV / SYNTHS / BASS MODEST! 2013- LIVE SET ARRANGER & PROGRAMMER ARRANGING / PROGRAMMING / MIX MODEST! 2013- PHILDEL MUSICAL DIRECTOR MD / BV / PROGRAMMING / BASS YEE INVENTIONS 2019 KIESZA PLAYBACK PROGRAMMING & MIX PROGRAMMING / MIX UNIVERSAL 2014 RIZZLE KICKS PLAYBACK PROGRAMMING & MIX PROGRAMMING / MIX ISLAND 2011-2014 BLUEY ROBINSON PLAYBACK PROGRAMMING & MIX PROGRAMMING / MIX LONDON VILLAGE 2013 KATE HAVNEVIK LIVE BAND MEMBER (CHINESE TOUR 2015) BV / BASS CONTINENTICA 2015 FROU FROU PLAYBACK & SYNTH PROGRAMMING PROGRAMMING ISLAND 2003 ANDREW MONTGOMERY MUSICAL DIRECTOR MD / BV / PROGRAMMING / BASS RULED BY DREAMS 2014-2015 TEMPOSHARK MUSICAL DIRECTOR MD / PROGRAMMING PAPER & GLUE 2007-2010 STUDIO BRITNEY SPEARS SINGLE – “EVERYTIME” (UK #1) PROGRAMMING / MIX BMG 2004 EP – CHAOTIC PROGRAMMING / MIX BMG 2005 SUGABABES ALBUM – THREE (UK #3) PROGRAMMING / MIX ISLAND 2003 ALBUM – TALLER IN MORE WAYS (UK #1) PROGRAMMING / MIX ISLAND 2005 FROU FROU ALBUM – SHREK 2 OST (US #8) PROGRAMMING / MIX DREAMWORKS 2004 ALBUM – DETAILS PROGRAMMING / MIX ISLAND 2002 ALISON MOYET ALBUM – THE TURN: DELUXE EDITION MIX COOKING VINYL 2015 ALBUM – MINUTES & SECONDS LIVE BACKING VOCALS / SYNTHS / MIX COOKING VINYL 2014 ALANIS MORISSETTE ALBUM – FLAVORS OF ENTANGLEMENT (US #8) PROGRAMMING / BVs WARNERS 2008 ROBYN ALBUM – DON’T STOP THE MUSIC PROGRAMMING / MIX BMG -

Music, Media and Technological Creativity in the Digital Age

Nordisk musikkpedagogisk forskning. Årbok 18 2017, 9-22 Nordic Research in Music Education. Yearbook Vol. 18 2017, 9–22 Music, media and technological creativity in the digital age Anne Danielsen Keynote on the 20th conference of the Nordic Network for Research in Music Education: “Technology and creativity in music education” March 8–10, 2016, Hedmark University College, Hamar, Norway The creative use of new digital technology has changed how music is produced, distributed, and consumed, as well as how music sounds. In this keynote, I will begin by examining some creative examples of music production in the digital age, focusing on two new sonic expressions within the field of popular music that have been produced through the unorthodox application of the digital audio workstation, or DAW, and more precisely through manipulations of rhythm and manipulations of the voice, respectively. Then I will discuss new patterns of use and personalized music “consumption,” using playlist creation in streaming services as my point of departure. Lastly, I will address how the two spheres of production and consumption meet in the so-called prosumption practices that have arisen in the digital era in the form of remix, sample and mashup music. 9 Anne Danielsen Creating with technology The topic of this conference is technology and creativity, which concerns machines often framed as a tension between human performance (creativity) and automated and humans and their relationship. Within the field of music, this relationship is specialty. Throughout the 1970s and even up to the advent of digital recording in the procedures (technology). This is certainly so within the field of rhythm, which is my dichotomy of human versus machine. -

Workplace Harassment in the Contemporary Music Industries of Australia and New Zealand

TUNESMITHS AND TOXICITY: WORKPLACE HARASSMENT IN THE CONTEMPORARY MUSIC INDUSTRIES OF AUSTRALIA AND NEW ZEALAND by Jeffrey Robert Crabtree Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy under the supervision of Professor Mark Evans and Doctor Susie Khamis University of Technology Sydney Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences August, 2020 CERTIFICATE OF ORIGINAL AUTHORSHIP I, Jefrey Robert Crabtree, declare that this thesis is submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the award of Doctor or Philosophy in the School of Communications at the University of Technology Sydney. This thesis is wholly my own work unless otherise referenced or acknowledged. In addition, I certify that all information sources and literature used are indicated in the thesis. This document has not been submitted for qualifications at any other academic institution. This research is supported by the Australian Government Research Training Program. Signature: Production Note: Signature removed prior to publication. Date: ii ACKOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to acknowledge the incredible support of my wife, who was not only very encouraging but also incredibly understanding whilst in the throes of completing her own doctorate at the same time as this study. I acknowledge my two highly talented daughters who inspire me with their creativity. Both of them have followed music careers and this research was undertaken in the hope that the working environment of the music industry will become a more welcoming space for women. I also wish to recognise my extraordinary supervisors, Professor Mark Evans and Doctor Susie Khamis, whose wise counsel and steady hands have guided this work. -

Led Zeppelin R.E.M. Queen Feist the Cure Coldplay the Beatles The

Jay-Z and Linkin Park System of a Down Guano Apes Godsmack 30 Seconds to Mars My Chemical Romance From First to Last Disturbed Chevelle Ra Fall Out Boy Three Days Grace Sick Puppies Clawfinger 10 Years Seether Breaking Benjamin Hoobastank Lostprophets Funeral for a Friend Staind Trapt Clutch Papa Roach Sevendust Eddie Vedder Limp Bizkit Primus Gavin Rossdale Chris Cornell Soundgarden Blind Melon Linkin Park P.O.D. Thousand Foot Krutch The Afters Casting Crowns The Offspring Serj Tankian Steven Curtis Chapman Michael W. Smith Rage Against the Machine Evanescence Deftones Hawk Nelson Rebecca St. James Faith No More Skunk Anansie In Flames As I Lay Dying Bullet for My Valentine Incubus The Mars Volta Theory of a Deadman Hypocrisy Mr. Bungle The Dillinger Escape Plan Meshuggah Dark Tranquillity Opeth Red Hot Chili Peppers Ohio Players Beastie Boys Cypress Hill Dr. Dre The Haunted Bad Brains Dead Kennedys The Exploited Eminem Pearl Jam Minor Threat Snoop Dogg Makaveli Ja Rule Tool Porcupine Tree Riverside Satyricon Ulver Burzum Darkthrone Monty Python Foo Fighters Tenacious D Flight of the Conchords Amon Amarth Audioslave Raffi Dimmu Borgir Immortal Nickelback Puddle of Mudd Bloodhound Gang Emperor Gamma Ray Demons & Wizards Apocalyptica Velvet Revolver Manowar Slayer Megadeth Avantasia Metallica Paradise Lost Dream Theater Temple of the Dog Nightwish Cradle of Filth Edguy Ayreon Trans-Siberian Orchestra After Forever Edenbridge The Cramps Napalm Death Epica Kamelot Firewind At Vance Misfits Within Temptation The Gathering Danzig Sepultura Kreator -

Imogen Heap As Musical Cyborg: Renegotiations of Power, Gender and Sound

Proceedings of the 4th Art of Record Production Conference 1 University of Massachusetts Lowell. 14th – 16th November 2008 Imogen Heap as Musical Cyborg: Renegotiations of Power, Gender and Sound Alexa Woloshyn Faculty of Music, University of Toronto, Canada [email protected] Abstract instruments, including cello, clarinet (Retka), and a “hilarious keyboard with boss-nova presets” (Gilbey 2005). Imogen Heap, British electronica artist, has had a Her first significant opportunity to experiment with successful solo and collaborative career since her 1998 electronic music technology was at the private boarding release of I Megaphone. She became a widespread name in school she attended as a young teenager. Heap clashed with 2004 after the song ‘Let Go’ from her collaborative album her music teacher, who punished her by sending her alone to with Guy Sigsworth, Details, was used in the film Garden a small room. Left in the room with an Atari computer, State. Following this success, Heap returned to solo work with Mac Classic 2 and Notator, and the large manual, Heap and released Speak for Yourself in 2005. Through an began to experiment and gained an interest in building her analysis of Heap’s musical development from her earliest own studio (Gilbey 2005). She formalized her training in musical experiences to her latest solo endeavors, this paper production at the BRIT school of Performing Arts & demonstrates Heap’s renegotiations of power, gender and Technology in Croyden, Surrey, from 1992 until 1995. sound allowed by the reconfigurations of institutional and In 1998, Heap released her first solo album I Megaphone commercial structures, which were enabled by the with Almo Sounds. -

Couples Retreat Is a Predictable Comedy with Artist: the Dutchess and the Duke Only a Few Solid Laughs

Arts&Entertainment AtTheMovies SoundCheck Couples Retreat is a predictable comedy with Artist: The Dutchess and the Duke only a few solid laughs. Album: Sunset / Sunrise Genre: Folk Revival Directed by Peter Billingsley. Written by Vince Vauhn and Jon Favreau. Starring Vaughn, Favreau and Malin Ackerman. BY TROY FARAH • THE LUMBERJACK Running Time: 107 minutes. hen an acoustic ballad and the lyrics are rehashed senti- Rated PG-13. is good, it’s called folk. ments from the ‘60s. BY GARY SUNDT • THE LUMBERJACK WWhen it sucks, it’s called The sunset arrives first in this country. Well, The Dutchess and the album, but there’s little hope of a ouples Retreat is a film because of their mannerisms and Favreau and Vaughn have had Duke’s sophomore album Sunset / sunrise. “Never Had A Chance” is about couples attending a inflections. Their dialogue has lit- a checkered career as collaborators Sunrise is a little of both. Drawing a breakup song that focuses bitterly Crelationship revival seminar tle substance, but how they use it (the great Swingers, the less great heavy influences from Bob Dylan on the past. In “Hands,” Lortz sings, on a beautiful tropical island. The evokes a chuckle here and there. The Break-Up), and the ending to and Lou Reed, The Dutchess and “The sun comes up / I’m counting pairs’ situations are mere examples But when I say those perfor- Couples Retreat hits home the fact The Duke still can’t seem to move the days I’ve got left,” completely of basic common relationship trou- mances pull the movie through, that this is not one of their stron- past their roots. -

Download PDF File

ANNOUNCED TODAY: T H E M U S I C O F H A R R Y P O T T E R A N D T H E C U R S E D C H I L D IN FOUR CONTEMPORARY SUITES BY IMOGEN HEAP WILL BE RELEASED 2 NOVEMBER 2018 AVAILABLE NOW TO PRE-ORDER AWARD-WINNING SCORE FEATURED IN A NEW ALBUM OF MUSIC BY GRAMMY & IVOR NOVELLO AWARD-WINNING COMPOSER & INNOVATOR IMOGEN HEAP Today, 20 September 2018, Producers Sonia Friedman and Colin Callender are proud to announce that The Music of Harry Potter and the Cursed Child, an album of music from the internationally acclaimed stage production, will be released on 2 November 2018. /more… -2- The Music of Harry Potter and the Cursed Child is written, composed, performed and recorded by Grammy and Ivor Novello Award-winner Imogen Heap. It is presented as four contemporary musical suites, each showcasing one of the play’s theatrical acts. This unique new album format from Imogen Heap chronologically features the music heard in the stage production, further reworked to transport listeners on a sonic journey through the world of Harry Potter and the Cursed Child. The Music of Harry Potter and the Cursed Child will be released by Sony Music Masterworks, and available in stores as well as digitally on 2 November 2018, with pre-orders available now at https://HarryPotter.lnk.to/HARRYPOTTERANDTHECURSEDCHILDPR Imogen Heap said “This album is like nothing I’ve ever attempted before. It’s four suites containing music from each of the four acts of the play, Harry Potter and the Cursed Child. -

Cultural Leaders a Community of Over 40 Cultural Leaders Joins the Annual Meeting in Davos to Help Inspire Responsive and Responsible Leadership

Cultural Leaders A community of over 40 Cultural Leaders joins the Annual Meeting in Davos to help inspire responsive and responsible leadership. Zarifa Adiba, Kabul Zarifa Adiba is a musician playing the viola and one of the conductors of the Afghan Women’s Orchestra, the first all-female Afghan orchestra based at the Afghanistan National Institute of Music. In Davos, she will join the orchestra to perform the closing concert before embarking on tour in Europe. Carol Becker, New York In her role as Dean of the Columbia School of the Arts, Carol Becker has helped to launch international programmes for screen and television writing, film production and literary translation. She has written extensively about the impact of art and artists on society. Becker also worked closely with the World Economic Forum’s Global Leadership Fellows to develop a unique programme on leadership development through art practice. Lonnie Bunch, Washington DC Lonnie Bunch is the founding Director of the Smithsonian Institution’s brand-new National Museum of African American History and Culture on the National Mall in Washington DC. A historian and educator, Bunch has unique insights on embracing history to address current challenges in the US and around the world. Matt Damon, New York Matt Damon is a prominent actor, film producer and screenwriter. He is passionate about alleviating the global water crisis. He is the co-founder of Water. org, which seeks to ensure that everyone in the world has access to safe water and basic sanitation. Damon is a 2014 recipient of the Crystal Award. Andrea Bandelli, Dublin Andrea Bandelli is the Executive Director of Science Gallery International (SGI). -

November 25, 2020 the Musicrow Weekly Wednesday, November 25, 2020

November 25, 2020 The MusicRow Weekly Wednesday, November 25, 2020 Taylor Swift, Brittany Howard, Ingrid Andress, Miranda Lambert Among Top Grammy Nominees SIGN UP HERE (FREE!) If you were forwarded this newsletter and would like to receive it, sign up here. THIS WEEK’S HEADLINES Taylor Swift, Brittany Howard, Ingrid Andress, Miranda Lambert Among Top Grammy Nominees 29th Annual Tin Pan South Sets Dates For 2021 The nominees for The 63rd Grammy Awards were announced Tuesday (Nov. 24) by Chair and Interim Recording Academy President/CEO Morgan Wallen Notches Harvey Mason Jr. and an eclectic group of past Grammy winners, Fourth Consecutive No. 1 nominees and other special guests, including artists Lauren Daigle, Mickey Guyton, Megan Thee Stallion, Dua Lipa, Pepe Aguilar, Yemi Alade, Nicola Benedetti, and Imogen Heap, as well as CBS This Dan + Shay, Kane Brown, Morning anchor Gayle King and The Talk host Sharon Osbourne. Maren Morris, Blake Shelton Earn American This year’s nominees were selected from more than 23,000 submissions Music Awards Wins across 83 categories, reflecting work that defined the year in music (Sept. 1, 2019 — Aug. 31, 2020). The final round of Grammy voting is Dec. 7, 2020 — Jan. 4, 2021. The 63rd Grammy Awards will be Country Hit Maker & Opry broadcast on CBS on Sunday, Jan. 31 at 8 p.m. ET. Star Hal Ketchum Dies The Recording Academy also announced The Daily Show host and Artist Visit: Restless Road Grammy-nominated comedian Trevor Noah as host of The 63rd Grammy Awards. This will be the first time Noah will serve as host. -

2020 Trends Report

QUARTER 4 2020 • ISSUE 430 2020 TRENDS REPORT Covid19 • Streaming Economics • #TheShowMustBePaused • Livestreaming • TikTok • Catalogues • Podcasts • Gaming • Antitrust • K-Pop • India • Africa • Bandcamp • China • Playlists • SoundCloud • Tips • Fake Streams • AI Music And Much, Much More! 1 Quarter Four 2020/Issue 430 www.musically.com ❱ Introduction Music Ally’s final report every year picks As a team, like every company, we had to figure out out the key trends of the past 12 months remote working and adapt our business to the new that we’ve seen in the music industry and realities, not to mention (again, like everyone) the stresses around keeping ourselves and our friends its digital ecosystem. and families safe. Perhaps the 2020 edition should just be a giant But here we are, at the end of 2020, proud of our printable poster of the Covid-19 coronavirus. But team and also proud of the wider music industry. nobody wants that on their walls. Hard work, innovation and lessons learned for the future is the story of 2020, rather than the As you’re hopefully well aware, Music Ally’s culture coronavirus. We hope this report gets that across. is one of curiosity and optimism. Our company was founded in 2002 at the height of the music industry’s Stuart Dredge misery around online piracy, and right from the start Editor, our message was that beyond filesharing there were Music Ally so many reasons to be excited about how digital technology could shape the industry. That natural optimism didn’t always come easily in 2020. thereport ❱ Introduction 2 Quarter Four 2020/Issue 430 www.musically.com The year of Covid-19 Well, what else would be the biggest trend of this cursed good viral-marketing strategy" – still true by the way) then 1.year? We racked our brains for a way to relegate Covid-19 in a story wondering "could the coronavirus outbreak affect the rankings, but the novel coronavirus reigns supreme. -

THE UNLV CHORAL ENSEMBLES David B

• Department of MUSIC College of Fine Arts presents THE UNLV CHORAL ENSEMBLES David B. Weiller and Jocelyn K. Jensen, conductors PROGRAM LAMPROPHONY Gianni Becker, director Imogen Heap Hide and Seek (b. 1977) arr. by Gianni Becker Pentatonix Run to You Cheyna Alexander, Eliysheba Anderson Tianci Jay Zheng, Gianni Becker, Xavier Brown WOMEN'S CHORUS J Jason Corpuz, piano Johann Sebastian Bach Aria from Orchestral Suite #3 (1685-1750) arr. by Malcolm V. Edwards Anders Edenroth Bumble Bee (b. 1963) CHAMBER CHORALE Jae Ahn-Benton, piano William Byrd Mass for Five Voices (1567-1643) Agn_us Dei _ Brian Edward Galante On Meditation (b. 1974) Johann Sebastian Bach Mass in G Major, BWV 236 Gloria VARSITY MEN'S GLEE CLUB Barbara Buer, piano Anonymous (Songs of Yale) We Meet Again Tonight Israeli Folk Song Tum Balalaika arr. by Walter Ehret David Conte Alleluia (b. 1955) Johann Pachelbel Canon in D (1653-1706) arr. Noel Goemanne Intermission (10 minutes) CONCERT SINGERS Henry Purcell Come, Ye Sons of Art, Z. 323 (1659-1695) I. Symphony II. Come, Ye Sons of Art (solo and chorus) Ill. Sound the Trumpet {duet) IV. Come, Ye Sons of Art (chorus) V. Strike the Viol (solo) VI. The Day That Such a B~ ssing Gave (solo and chorus) VII. Bid the Virtues (solo) VIII. These Are the Sacred Charms (solo) IX. Se~ Nature, Rejoicing (duet and chorus) Alex Price, countertenor Maia Julianne Thielen, soprano Deanna Woods, mezzo-soprano Kurt Ludwig Sedlmeir, baritone Donovan Crespo, baritone Lacy Burchfield, soprano Nicholas Hummel, baritone Brandon Denman and Amber Epstein, flute Sharon Nakama and Joey Schrotberger, oboe Allison Mcswain and Justin Bland, trumpet Clifford Richardson and Peter Goomroyan, violin Orei Odents, viola Pishoi Nassif, cello; Bronson Foster, bassoon Manuel Gamazo, timpani - Jae Ahn-Benton, harpsichord Friday, November 21, 2014 7:30 p.m.