The State Council in China

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Confucianism, "Cultural Tradition" and Official Discourses in China at the Start of the New Century

China Perspectives 2007/3 | 2007 Creating a Harmonious Society Confucianism, "cultural tradition" and official discourses in China at the start of the new century Sébastien Billioud Édition électronique URL : http://journals.openedition.org/chinaperspectives/2033 DOI : 10.4000/chinaperspectives.2033 ISSN : 1996-4617 Éditeur Centre d'étude français sur la Chine contemporaine Édition imprimée Date de publication : 15 septembre 2007 ISSN : 2070-3449 Référence électronique Sébastien Billioud, « Confucianism, "cultural tradition" and official discourses in China at the start of the new century », China Perspectives [En ligne], 2007/3 | 2007, mis en ligne le 01 septembre 2010, consulté le 14 novembre 2019. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/chinaperspectives/2033 ; DOI : 10.4000/chinaperspectives.2033 © All rights reserved Special feature s e v Confucianism, “Cultural i a t c n i e Tradition,” and Official h p s c r Discourse in China at the e p Start of the New Century SÉBASTIEN BILLIOUD This article explores the reference to traditional culture and Confucianism in official discourses at the start of the new century. It shows the complexity and the ambiguity of the phenomenon and attempts to analyze it within the broader framework of society’s evolving relation to culture. armony (hexie 和谐 ), the rule of virtue ( yi into allusions made in official discourse, we are interested de zhi guo 以德治国 ): for the last few years in another general and imprecise category: cultural tradi - Hthe consonance suggested by slogans and tion ( wenhua chuantong ) or traditional cul - 文化传统 themes mobilised by China’s leadership has led to spec - ture ( chuantong wenhua 传统文化 ). ((1) However, we ulation concerning their relationship to Confucianism or, are excluding from the domain of this study the entire as - more generally, to China’s classical cultural tradition. -

Hong Kong, 1997 : the Politics of Transition

The Politics of Transition Enbao Wang .i.' ^ m iip Canada-Hong Kong Resource Centre ^ff from Hung On-To Memorial Library ^<^' Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2010 with funding from IVIulticultural Canada; University of Toronto Libraries http://www.archive.org/details/hongkong1997poli00wang Hong Kong, 1997 Canada-Hong Kong Resource Centre Spadina 1 Crescent, Rjn. Ill • Tbronto, Canada • M5S lAl Hong Kong, 1997 The Politics of Transition Enbao Wang LYNNE RIENNER PUBLISHERS BOULDER LONDON — Published in the United States of America in 1995 by L\ nne Rienner Publishers. Inc. 1800 30lh Street. Boulder. Colorado 80301 and in the United Kingdom by U\ nne Rienner Publishers. Inc. 3 Henrietta Street. Covenl Garden. Uondon WC2E 8LU © 1995 by Lynne Rienner Publishers, inc. All rights reserved. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Wang. Enbao. 1953- Hong Kong. 1997 : the politics of transition / Enbao Wang. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 1-55587-597-1 (he: alk. paper) 1 . Hong Kong—Politics and government. 2. Hong Kong—Relations China. 3. China—Relations — Hong Kong. 4. China— Politics and government— 1976- 1. Title. bs796.H757W36 1995 951.2505—dc20 95-12694 CIP British Cataloguing in Publication Data A Cataloguing in Publication record for this book is available from the British Uibrarv. This book was t\peset b\ Uetra Libre. Boulder. Colorado. Printed and bound in the United States of .America The paper used in this publication meets the requirements @ of the .American National Standard for Permanence -

YAO-DISSERTATION-2016.Pdf

CONSUMING SCIENCE: A HISTORY OF SOFT DRINKS IN MODERN CHINA A Dissertation Presented to The Academic Faculty by Liang Yao In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the School of History and Sociology Georgia Institute of Technology May 2016 COPYRIGHT © 2015 BY LIANG YAO CONSUMING SCIENCE: A HISTORY OF SOFT DRINKS IN MODERN CHINA Approved by: Dr. Hanchao Lu, Advisor Dr. Laura Bier School of History and Sociology School of History and Sociology Georgia Institute of Technology Georgia Institute of Technology Dr. John Krige Dr. Kristin Stapleton chool of History and Sociology History Department Georgia Institute of Technology University at Buffalo Dr. Steven Usselman chool of History and Sociology Georgia Institute of Technology Date Approved: December 2, 2015 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would never have finished my dissertation without the guidance, help, and support from my committee members, friends, and family. Firstly, I would like to express my deepest gratitude to my advisor Professor Hanchao Lu for his caring, continuous support, and excellent intellectual guidance in all the time of research and writing of this dissertation. During my graduate study at Georgia Tech, Professor Lu guided me where and how to find dissertation sources, taught me how to express ideas and write articles like a historian. He provided me opportunities to teach history courses on my own. He also encouraged me to participate in conferences and publish articles on journals in the field. His patience and endless support helped me overcome numerous difficulties and I could not have imagined having a better advisor and mentor for my doctorial study. -

Xi Jinping and the Party Apparatus

Miller, China Leadership Monitor, No. 25 Xi Jinping and the Party Apparatus Alice Miller In the six months since the 17th Party Congress, Xi Jinping’s public appearances indicate that he has been given the task of day-to-day supervision of the Party apparatus. This role will allow him to expand and consolidate his personal relationships up and down the Party hierarchy, a critical opportunity in his preparation to succeed Hu Jintao as Party leader in 2012. In particular, as Hu Jintao did in his decade of preparation prior to becoming top Party leader in 2002, Xi presides over the Party Secretariat. Traditionally, the Secretariat has served the Party’s top policy coordinating body, supervising implementation of decisions made by the Party Politburo and its Standing Committee. For reasons that are not entirely clear, Xi’s Secretariat has been significantly trimmed to focus solely on the Party apparatus, and has apparently relinquished its longstanding role in coordinating decisions in several major sectors of substantive policy. Xi’s Activities since the Party Congress At the First Plenum of the Chinese Communist Party’s 17th Central Committee on 22 October 2007, Xi Jinping was appointed sixth-ranking member of the Politburo Standing Committee and executive secretary of the Party Secretariat. In December 2007, he was also appointed president of the Central Party School, the Party’s finishing school for up and coming leaders and an important think-tank for the Party’s top leadership. On 15 March 2008, at the 11th National People’s Congress (NPC), Xi was also elected PRC vice president, a role that gives him enhanced opportunity to meet with visiting foreign leaders and to travel abroad on official state business. -

An "Exceedingly Delicate Undertaking": Sino-American

An "exceedingly delicate undertaking": Sino-American science diplomacy, 1966–78 LSE Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/102296/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Millwood, Peter (2019) An "exceedingly delicate undertaking": Sino-American science diplomacy, 1966–78. Journal of Contemporary History. ISSN 0022-0094 (In Press) Reuse Items deposited in LSE Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the LSE Research Online record for the item. [email protected] https://eprints.lse.ac.uk/ An “Exceedingly Delicate Undertaking”: Sino-American Science Diplomacy, 1966–78 Pete Millwood International History Department, London School of Economics In the first half of the twentieth century, China sought to modernize through opening to the world. Decades of what would become a century of humiliation had disabused the country of its previous self-perceived technological superiority, as famously expressed by Emperor Qianlong to the British envoy George Macartney in 1793. The Chinese had instead become convinced that they needed knowledge from outside to become strong enough to resist imperial aggression. No country encouraged this opening more than the United States. Americans threw money and expertise at the training of Chinese students and intellectuals. The Rockefeller Foundation’s first major overseas project was the creation of China’s finest medical college and other US institutions followed Rockefeller’s lead by establishing dozens of Chinese universities and technical schools to train a new generation of Chinese scientists. -

Shen Yueyue, Vice-Chairwoman of the National People's Congress

Zhang Baowen, vice-chairman of the National People’s Congress standing committee, meets with Vaira Vike-Freiberga, president of the World Leardership Alliance, before the opening ceremony Shen Yueyue, vice-chairwoman of the National People’s Congress standing committee, poses with delegates to the reception for celebrating the 25th anniversary of the establishment of diplomatic relations between China and the Baltic states Contents Express News FOCUS 04 President Li Xiaolin Meets with Lord Powell, Member of the House of Lords of the UK Parliament / Wang Fan 04 Vice President Xie Yuan Meets with Delegation of Colombian Governors / Lin Zhichang 05 The Opening Ceremony of a Large-Scale Relics Touring Exhibition of Chinese Characters / Yu Xiaodong 05 Vice-President Lin Yi Meets with Premier of the British Virgin Islands / Wang Fan 10 06 Vice President Song Jingwu Meets with Mr. Kawamura Takeo / Fu Bo 06 Secretary-General Li Xikui Leads a Delegation to Jiangxi / Sun Yutian 07 China-Latin America and Caribbean 2016 Year of Culture Exchange / Wang Lijuan 07 The Chinese Culture Tour for Cultural Officials of Relevant Embassies in China 14 and Foreign Experts in Changsha / Gao Hui 08 Enjoy the Global “Music Journey” on the Doorstep / Chengdu Friendship Association 08 “Panda Chengdu”Shines in Ljubljana / Chengdu Friendship Association Global Vision 3020 09 G20 Hangzhou Summit Points the Way for the World Economy / He Yafei 2016 Imperial Springs International Forum 12 2016 Imperial Springs International Forum / Department of American & Oceanian Affairs -

The CCP Central Committee's Leading Small Groups Alice Miller

Miller, China Leadership Monitor, No. 26 The CCP Central Committee’s Leading Small Groups Alice Miller For several decades, the Chinese leadership has used informal bodies called “leading small groups” to advise the Party Politburo on policy and to coordinate implementation of policy decisions made by the Politburo and supervised by the Secretariat. Because these groups deal with sensitive leadership processes, PRC media refer to them very rarely, and almost never publicize lists of their members on a current basis. Even the limited accessible view of these groups and their evolution, however, offers insight into the structure of power and working relationships of the top Party leadership under Hu Jintao. A listing of the Central Committee “leading groups” (lingdao xiaozu 领导小组), or just “small groups” (xiaozu 小组), that are directly subordinate to the Party Secretariat and report to the Politburo and its Standing Committee and their members is appended to this article. First created in 1958, these groups are never incorporated into publicly available charts or explanations of Party institutions on a current basis. PRC media occasionally refer to them in the course of reporting on leadership policy processes, and they sometimes mention a leader’s membership in one of them. The only instance in the entire post-Mao era in which PRC media listed the current members of any of these groups was on 2003, when the PRC-controlled Hong Kong newspaper Wen Wei Po publicized a membership list of the Central Committee Taiwan Work Leading Small Group. (Wen Wei Po, 26 December 2003) This has meant that even basic insight into these groups’ current roles and their membership requires painstaking compilation of the occasional references to them in PRC media. -

N~Rb,E~~~~~ the E~Rorea~ CQ~M~~Ir.Y, ~~DT~E 9

Commission .' .....,-; '.-'.'" """. :-.' -' ".~- .-, of the European Communities Direc,torat~':General for'in'6rlii~tion ,'", \ THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITY AND THE PEOPLE'S REPUBLIC Of CHINA: INTRODUCTION - BACKGROUND 1 - J . l' . -.,:: , 'I '. C : '.~ ,-'-"". 2 ~~~p~~~~1~~;~~[~~N~rB,E~~~~~ THE E~ROrEA~ CQ~M~~Ir.Y, ~~D T~E THE TRADE AND ECONOMIC COOPERATION AGREEMENT BETWEEN THE ~~~Op'E~~ 3 COt+1UNiTY AND TH'['P['OPLEi'S"'REPUBLI'c'OF CHiNA" ," ", '-. ; l: ' :') .-' d'·t. ,;. ~ :;~ _'". ',':". PRO~OTION Of EXC~A~~,ES A~P CONTA~1S .. '. - .. ,',' :=. '. ' ...' '. , ''Training activities 4 (int;,erpreters~ statistica~ experts~ customs officisls - business' ril8~8g~ent'arid moa~r.niZa~~6r1) ." , ": ':; ..: ,Y\ "!" ,~"', c:: } ,'" ' .' '. '. " ' ;. ~ " Information snd study visits 5 .. "... ~~,:' ~ 'd~'- y' '. ", . :- NEW fORMS Of CONTACT BETWEEN THE pEOPLE'S REPUBLIC Of CHINA AND, 6 , THE' EUR~P~~'N. CO~UNrr.y.' ','" ' ," ",; THE TEXTILE AGREEMENJ BET,WEEN THE COMI':1U~nY AfliQ THE REPUBLIC 7 Of 'CHIN~ . , ,\ ' ,' !.;, " THE, GENERALISED. SYST,EM or PHEfER.~N~ES B TR,ADE pROMOJ IO~ E.Vt~~S 9 first EEC-China Business Week ~ ~~,' \.,,:~:~~ - . .:. ..' ,"-,-:.' ... :: Seminar on the re.f~~ ~f Cl:lin~' s foreign trade sYE!teni 9 Second EEC-China Business Week 9 .' i~' :,., !:'.: '.".- Sale of tec~nology seminar 10 - - . ~ .':. ;::; . Chin~8e, purchasing ~ission8 10 'Assessment of modernization needs 1.0 .. _'" ; . '. :~l<:; ~ Symposium of the European Committee on Cooperation of the Machine Tool 'Industries (CECIMO) in Beijing snd Shanghai 10 ! - -c" <... ~ .. -. .. ENERGY COOPERATION 11 ~GJ~~Jl~~~ A~D., TECH~OLOGICAL COOPERATION ~ ~~S,~A.~.Ylt 'A~P:: 9~VtLO~MEN:r ' 12 DATA-PROCESSING~ AND TELECOMMUNICATIONS COOPERATION 13 : .....; ..... .. .. ...- '-. : ,.. : . - ..: . , _. ~G~.IFULT.l,I~~~ T:~.C,WHC~~, :~~~~~~~I!OJ~' 13 EXCHANGE~ Of VISITS 13 NOVEMBER:.-. -

China Council for the Promotion of Peaceful National Reunification (CCPPNR) – a Tool for the Chinese Communist Party’S United Front Work

World Organization to Investigate the Persecution of Falun Gong China Council for the Promotion of Peaceful National Reunification (CCPPNR) – A Tool for the Chinese Communist Party’s United Front Work May 20, 2011 (first published) The China Council for the Promotion of Peaceful National Reunification (CCPPNR) presents itself as a non-governmental organization (NGO) aimed at peacefully unifying Taiwan. In fact, it is an organization under the United Front Work Department of the Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party. The CCPPNR frequently organizes public activities in its respective host countries and political circles. Under the title of NGO, it has established branches in different countries. Its goal is to establish and develop a political alliance – with the Chinese Communist Party being its core leadership alliance [1] – and carry out the Communist Party’s united front strategy to influence policymaking in its host countries, and to enhance the Chinese communist regime’s control and influence in the world. The CCPPNR in various countries were founded as NGOs but take orders from Beijing and implement Communist Party policies. This report exposes the CCPPNR as a tool for the Chinese Communist Party’s united front work. World Organization to Investigate the Persecution of Falun Gong Our mission To investigate the criminal conduct of all institutions, organizations, and individuals involved in the persecution of Falun Gong; to bring such investigations, no matter how long it takes, no matter how far and deep we have to search, to full closure; to exercise fundamental principles of humanity; and to restore and uphold justice in society. -

The Communist Party of China: I • Party Powers and Group Poutics I from the Third Plenum to the Twelfth Party Congress

\ 1 ' NUMBER 2- 1984 (81) NUMBER 2 - 1984 (81) THE COMMUNIST PARTY OF CHINA: I • PARTY POWERS AND GROUP POUTICS I FROM THE THIRD PLENUM TO THE TWELFTH PARTY CONGRESS Hung-mao Tien School of LAw ~ of MAaylANCI • ' Occasional Papers/Reprint Series in Contemporary Asian Studies General Editor: Hungdah Chiu Executive Editor: Mitchell A. Silk Managing Editor: Shirley Lay Editorial Advisory Board Professor Robert A. Scalapino, University of California at Berkeley Professor Martin Wilbur, Columbia University Professor Gaston J. Sigur, George Washington University Professor Shao-chuan Leng, University of Virginia Professor Lawrence W. Beer, Lafayette College Professor James Hsiung, New York University Dr. Lih-wu Han, Political Science Association of the Republic of China Professor J. S. Prybyla, The Pennsylvania State University Professor Toshio Sawada, Sophia University, Japan Professor Gottfried-Karl Kindermann, Center for International Politics, University of Munich, Federal Republic of Germany Professor Choon-ho Park, College of Law and East Asian Law of the Sea Institute, Korea University, Republic of Korea Published with the cooperation of the Maryland International Law Society All contributions (in English only) and communications should be sent to Professor Hungdah Chiu, University of Maryland School of Law, 500 West Baltimore Street, Baltimore, Maryland 21201 USA. All publications in this series reflect only the views of the authors. While the editor accepts responsibility for the selection of materials to be published, the individual author is responsible for statements of facts and expressions of opinion contained therein. Subscription is US $10.00 for 6 issues (regardless of the price of individual issues) in the United States and Canada and $12.00 for overseas. -

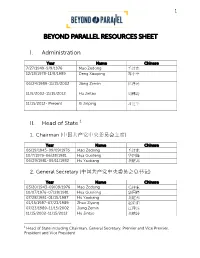

Beyond Parallel Resources Sheet

1 BEYOND PARALLEL RESOURCES SHEET I. Administration Year Name Chinese 7/27/1949-9/9/1976 Mao Zedong 毛泽东 12/18/1978-11/8/1989 Deng Xiaoping 邓小平 06/24/1989-11/15/2002 Jiang Zemin 江泽民 11/5/2002-11/15/2012 Hu Jintao 胡锦涛 11/15/2012- Present Xi Jinping 习近平 II. Head of State 1 1. Chairman (中国共产党中央委员会主席) Year Name Chinese 06/19/1945-09/09/1976 Mao Zedong 毛泽东 10/7/1976-06/28/1981 Hua Guofeng 华国锋 06/29/1981-09/11/1982 Hu Yaobang 胡耀邦 2. General Secretary (中国共产党中央委员会总书记) Year Name Chinese 03/20/1943-09/09/1976 Mao Zedong 毛泽东 10/07/1976-07/28/1981 Hua Guofeng 华国锋 07/28/1981-01/15/1987 Hu Yaobang 胡耀邦 01/15/1987-07/23/1989 Zhao Ziyang 赵紫阳 07/23/1989-11/15/2002 Jiang Zemin 江泽民 11/15/2002-11/15/2012 Hu Jintao 胡锦涛 1 Head of State including Chairman, General Secretary, Premier and Vice Premier, President and Vice President 2 11/15/2012-Present Xi Jinping 习近平 3. Premier (中华人民共和国国务院总理) Year Name Chinese 10/1949-01/1976 Zhou Enlai 周恩来 2/2/1976-09/10/1980 Hua Guofeng 华国锋 09/10/1980-11/24/1987 Zhao Ziyang 赵紫阳 11/24/1987-03/17/1998 Li Peng 李鹏 03/17/1998-03/16/2003 Zhu Rongji 朱镕基 03/16/2003-03/15/2013 Wen Jiabao 温家宝 03/15/2013-Present Li Keqiang 李克强 4. Vice Premier (中华人民共和国国务院副总理) Year Name Chinese 09/15/1954-12/21/1964 Chen Yun 陈云 12/21/1964-09/13/1971 Lin Biao 林彪 09/13/1971-09/10/1980 Deng Xiaoping 邓小平 09/10/1980-03/25/1988 Wan Li 万里 03/25/1988-3/05/1993 Yao Yilin 姚依林 3/25/1993-03/17/1998 Zhu Rongji 朱镕基 03/17/1998-03/06/2003 Li Lanqing 李岚清 03/06/2003-06/02/2007 Huang Ju 黄菊 06/02/2007-03/16/2008 Wu Yi 吴仪 03/16/2008-03/16/2013 Li Keqiang 李克强 03/16/2013-Present Zhang Gaoli 张高丽 5. -

Klint De Roodenbeke, Auguste (1816-1878) : Belgischer Diplomat Biographie 1868 Auguste T’Klint De Roodenbeke Ist Belgischer Gesandter in China

Report Title - p. 1 of 509 Report Title t''Klint de Roodenbeke, Auguste (1816-1878) : Belgischer Diplomat Biographie 1868 Auguste t’Klint de Roodenbeke ist belgischer Gesandter in China. [KuW1] Tabaglio, Giuseppe Maria (geb. Piacenza-gest. 1714) : Dominikaner, Professor für Theologie, Università Sapienza di Roma Bibliographie : Autor 1701 Tabaglio, Giuseppe Maria ; Benedetti, Giovanni Battista. Il Disinganno contraposto da un religioso dell' Ordine de' Predicatori alla Difesa de' missionarj cinesi della Compagnia di Giesù, et ad un' altro libricciuolo giesuitico, intitulato l' Esame dell' Autorità &c. : parte seconda, conchiusione dell' opera e discoprimento degl' inganni principali. (Colonia : per il Berges, 1701). https://archive.org/details/bub_gb_ZX__WZVH6zsC. [WC] 1709 Tabaglio, Giuseppe Maria ; Fatinelli, Giovanni Jacopo. Considerazioni sù la scrittura intitolata Riflessioni sopra la causa della Cina dopò ! venuto in Europa il decreto dell'Emo di Tournon. (Roma : [s.n.], 1709). https://archive.org/details/bub_gb_YWkGIznVv70C. [WC] Tabone, Vincent (Victoria, Gozo 1913-2012 San Giljan, Malta) : Politiker, Staatspräsident von Malta Biographie 1991 Vincent Tabone besucht China. [ChiMal3] Tacchi Venturi, Pietro (San Severino Marche 1861-1956 Rom) : Jesuit, Historiker Bibliographie : Autor 1911-1913 Ricci, Matteo ; Tacchi Venturi, Pietro. Opere storiche. Ed. a cura del Comitato per le onoranze nazionali con prolegomeni, note e tav. dal P. Pietro Tacchi-Venturi. (Macerata : F. Giorgetti, 1911-1913). [KVK] Tacconi, Noè (1873-1942) : Italienischer Bischof von Kaifeng Bibliographie : erwähnt in 1999 Crotti, Amelio. Noè Tacconi (1873-1942) : il primo vescovo di Kaifeng (Cina). (Bologna : Ed. Missionaria Italiana, 1999). [WC] Tachard, Guy (Marthon, Charente 1648-1712 Chandernagor, Indien) : Jesuitenmissionar, Mathematiker Biographie Report Title - p. 2 of 509 1685 Ludwig XIV.