1 Later Nineteenth-Century Women Philosophers On

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reincarnation Profile

Reincarnation By Eric Pement Introduction Reincarnation is the popular belief that after death the human soul or inner self leaves its former body and is eventually reborn into a new body. An earlier term is transmigration of the soul, indicating that the soul can migrate from one body to another. The ancient Greeks called it metempsychosis (“after ensoulment”) and palingenesis (“repeated birth”).1 Reincarnationist ideas have appeared in many lands, including island cultures having no contact with religions from the mainland. Though Greek philosopher and mathematician Pythagoras (570–495 BC) left no writings, his students claimed he remembered four previous lives and promoted metempsychosis. The works of Plato (428–348 BC) have been well preserved; he taught reincarnation, as did his Greek successors. The theory of reincarnation flourished in four religions from India: Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism, and Sikhism. It is not in the oldest Hindu scriptures (the Vedas), but it appears in the Upanishads (about 700 BC) and later works.2 All four religions differ significantly in how they explain reincarnation. In Europe and America, the details were modified perhaps to sound more acceptable to Western ears, but the core theme remained: the soul is immortal and death is not final—only a recurring transition in an endless cycle of birth, death, and rebirth into a new form. Many reincarnationists believe that when one reaches sufficient spiritual illumination, the cycle of rebirth will cease and the soul will reunite with God, Brahman, or whatever they deem Ultimate Reality. Fundamental Questions Beliefs about reincarnation vary widely. Perhaps the best way to focus the topic is to ask a few questions. -

Theosophy Is of the Devil by David J

Theosophy is of the Devil By David J. Stewart I could have just as easily saved this article under "New Age" or "Witchcraft," because there's not a dime's difference between the two. I saved it under "New Age" because the primary agenda of Theosophy is to further the New World Order, i.e., the Beast system of the coming Antichrist. The following historical information concerning Theosophy is a quote from Wikipedia.com... Photo to Right: Occultist and Satan worshipper, Helena Petrovna Blavatsky Theosophy, literally "god-wisdom" (Greek: θεοσοφία theosophia), designates several bodies of ideas. The 6th century neo-platonist Pseudo-Dionysius seems to have been the first philosopher the term applied to. There was a group of Renaissance philosophers: Cornelius Agrippa, Paracelsus, Robert Fludd, and, especially, Jacob Boehme; the Enlightenment theologian Emanuel Swedenborg was influenced by these. And finally, the word was revived in the nineteenth century by Helena Petrovna Blavatsky to designate her religious philosophy which holds that all religions are attempts by humanity to approach the absolute, and that each religion therefore has a portion of the truth. Together with Henry Steel Olcott, William Quan Judge, and others, Blavatsky founded the Theosophical Society in 1875. This society has since split into a number of organizations, some of which no longer use the term "theosophy." SOURCE: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Theosophy Please notice that Helena Petrovna Blavatsky founded the Theosophical Society in 1875. Her most popular work was a two- volume book she wrote titled 'The Secret Doctrine,' in which she woefully states... "Lucifer represents.. Life. -

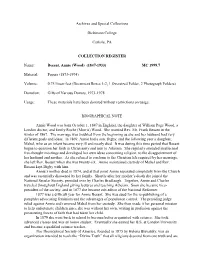

Archives and Special Collections

Archives and Special Collections Dickinson College Carlisle, PA COLLECTION REGISTER Name: Besant, Annie (Wood) (1847-1933) MC 1999.7 Material: Papers (1873-1974) Volume: 0.75 linear feet (Document Boxes 1-2, 1 Oversized Folder, 2 Photograph Folders) Donation: Gifts of Various Donors, 1973-1978 Usage: These materials have been donated without restrictions on usage. BIOGRAPHICAL NOTE Annie Wood was born October 1, 1847 in England, the daughter of William Page Wood, a London doctor, and Emily Roche (Morris) Wood. She married Rev. Mr. Frank Besant in the winter of 1867. The marriage was troubled from the beginning as she and her husband had very different goals and ideas. In 1869, Annie had a son, Digby, and the following year a daughter, Mabel, who as an infant became very ill and nearly died. It was during this time period that Besant began to question her faith in Christianity and turn to Atheism. She regularly attended intellectual free-thought meetings and developed her own ideas concerning religion, to the disappointment of her husband and mother. As she refused to conform to the Christian life required by her marriage, she left Rev. Besant when she was twenty-six. Annie maintained custody of Mabel and Rev. Besant kept Digby with him. Annie’s mother died in 1874, and at that point Annie separated completely from the Church and was essentially disowned by her family. Shortly after her mother’s death she joined the National Secular Society, presided over by Charles Bradlaugh. Together, Annie and Charles traveled throughout England giving lectures and teaching Atheism. -

The Universal Dimension: William Loftus Hare's Pivotal Contribution To

Quaker Studies Volume 10 | Issue 2 Article 8 2006 The niU versal Dimension: William Loftus Hare's Pivotal Contribution to London Yearly Meeting Tony Adams [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/quakerstudies Part of the Christian Denominations and Sects Commons, and the History of Christianity Commons Recommended Citation Adams, Tony (2006) "The nivU ersal Dimension: William Loftus aH re's Pivotal Contribution to London Yearly Meeting," Quaker Studies: Vol. 10: Iss. 2, Article 8. Available at: http://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/quakerstudies/vol10/iss2/8 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ George Fox University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Quaker Studies by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ George Fox University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. QUAKER STUDIES 10/2 (2006) [256-280) ADAMS THE UNIVERSAL DIMENSION 257 ISSN 1363-013X UNIVERSALISM WITHIN FRIENDS From the outset, universalism was a significant feature of the Quaker faith. The pos sibility of salvation beyond the particularism of the Jewish race that had been voiced by Amos (9:7), and by Paul's assertions (Rom. 9-1 1) that the special call oflsrael was not a privilege but a responsibility, which he envisaged as a re-integration of all man THE UNIVERSAL DIMENSION: kind in Christ, was taken up seriously. The divine power or principle of the Holy WILLIAM LOFTUS HARE'S PIVOTAL CONTRIBUTION Spirit was said by George Fox to have been active not only during Old Testament times in Jewish society, but in other cultures too. -

The University of Sydney Copyright in Relation to This Thesis·

The University of Sydney Copyright in relation to this thesis· Under the Copyright Act 1968 (several provision of which are referred to below), this thesis must be used only under the normal conditions of scholarly fair dealing for the purposes of research, criticism or review. In particular no results or conclusions should be extracted from it. nor should it be copied or closely paraphrased in whole or in part without the written consent of the author. Proper written acknowledgement should be made for any assistance obtained from this thesis. Under Section 35(2) of the Copyright Act 1968 'the author of a literary, dramatic, musical or artistic work is the owner of any copyright subsisting in the work'. By virtue of Section 32( I) copyright 'subsists in an original literary, dramatic, musical or artistic work that is unpublished' and of which the author was an Australian citizen, an Australian protected person or a person reSident in Australia. The Act. by Section 36( I) provides: 'Subject to this Act. the copyright in a literary, dramatic, musical or artistic work is mfringed by a person who, not being the owner of the copyright and without the licence of the owner of the copyright, does in Australia. or authorises the doing in Australia of, any act comprised in the copyright'. Section 31 (I )(a)(i) provides that copyright includes the exclusive right to 'reproduce the work in a material form'.Thus, copyright IS mfringed by a person who, not being the owner of the copyright. reproduces or authorises the reproduction of a work. -

Theosophy Profile

Theosophy By Viola Larson Founder: Helena Petrovna Blavatsky Founding Date: 1875 Location: New York Unique Terms: Mahatmas, Clairvoyant Knowledge, Karma, Reincarnation. Publications: Magazines: Quest (The Theosophical Society in America), Sunrise: Theosophic Perspectives (The Theosophical Society); Books by Helena Blavatsky, Henry Olcott, W. Q. Judge, Annie Besant, Grace Knoche and others. History Theosophy, as a religious sect, began in the nineteenth century. It developed out of the growing interest in Spiritualism and is a belief system grounded in occult and Eastern thought. Moreover, it is totally Gnostic possessing the two important tenets of Gnostic religion: knowledge as a way of salvation and a hierarchy of beings based on the possession of such knowledge. Helena Petrovna Blavatsky, with the help of William Q. Judge, Henry S. Olcott and others, founded the original Theosophical Society in New York, in 1875. Although now numerically small, Theosophy’s philosophy has influenced the New Age movement of today. The prolific writing and influence of Blavatsky and others in the society are perhaps more important than the organization itself. Helena Petrovna Blavatsky was born in Russia in 1831. As a young woman she was involved in Spiritualism. She moved to New York in 1873. In 1875 she founded the Theosophy Society. When first organized the Society’s basic text was Isis Unveiled, written by Blavatsky. In 1879 Blavatsky and Olcott visited India. Theosophy’s main headquarters was established in Adyar, India. Since that visit both Buddhist and Hindu concepts have influenced the ideology of Theosophy. J. Gordon Melton writes, “[A]t this time, the concept of the mahatmas came to the fore.” Melton elaborates: “From a special altar in her home at Adyar and a few other places, letters from the masters in the spirit world began to arrive.”1 Blavatsky used the extrasensory messages as a means of ascertaining truth. -

South Asians and the Theosophical Society, 1879-1930 Maria Moritz

Globalizing “Sacred Knowledge”: South Asians and the Theosophical Society, 1879-1930 by Maria Moritz a Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History Approved Dissertation Committee Professor Harald Fischer-Tiné, ETH Zürich Professor Nicola Spakowski, Universität Freiburg Professor Hans Kippenberg, Jacobs University Bremen Professor Sebastian Conrad, Freie Universität Berlin Date of Defense: 23 March 2012 School of Humanities and Social Sciences Statutory Declaration (on Authorship of a Dissertation) I, Maria-Sofia Moritz, hereby declare that I have written this PhD thesis independently, unless where clearly stated otherwise. I have used only the sources, the data and the support that I have clearly mentioned. This PhD thesis has not been submitted for conferral of degree elsewhere. I confirm that no rights of third parties will be infringed by the publication of this thesis. Berlin, April 27, 2017 Signature ___________________________________________________________ Contents Acknowledgements .............................................................................................................................. 4 List of Illustrations ............................................................................................................................... 5 Abbreviations ........................................................................................................................................ 6 Introduction .......................................................................................................................................... -

Rudolf Steiner and the Jewish Question Peter Staudenmaier Marquette University, [email protected]

Marquette University e-Publications@Marquette History Faculty Research and Publications History, Department of 1-1-2005 Rudolf Steiner and the Jewish Question Peter Staudenmaier Marquette University, [email protected] Published version. Leo Baeck Institute Yearbook, Vol. 50, No. 1 (2005): 127-147. Permalink. © 2005 Oxford University Press. Used with permission. Antisemitism 128 Peter Staudenmaier writings.3 An overvie w of Steiner's shifting perspective onJudaism and antisemitism may provide some insight into these enigmati c questions. What follows is a brief and necessaril y schema tic attempt to summa rise Steiner's protean stance on the 'J ewish question", that fa teful topi c comma nding such intense interest a mong Steiner's contemporaries. RUDOLF STEINER AND THE 'JEWISH QUESTION" The subject of anthroposophy's relationship toJews and Judaism is a complex and contentious one, in part because of the widely dispa ra te viewpoints represented among past and present a nthroposophists. A number of Steiner's followers came fromJe\vish backgrounds; the early Zionist leader Hugo Bergmann, for example, was for a time a devoted student a nd admirer of Steiner. At the same time, both Steiner's immediate predecessors a nd colleagues, the theosophists, and several of his successors within the first generation of anthroposophists promoted a sharp contrast between '1\ryans" and "Semites" tha t systematically privileged the former while systematically denigrating the latter. 4 Steiner's collected works, moreover, totalling more tha n 350 volumes, contain pelvasive inte rnal contradictio ns and inconsistencies on racial and national questions. Alternating betvveen patently racist and a nti-racist precepts, his overall racial theories a re somewhat difficult to reconstruct, much less summa rise adequately. -

Theosophy, Culture, and Politics in Honolulu, 1890-1920

FRANK J. KARPIEL Theosophy, Culture, and Politics in Honolulu, 1890-1920 IN THE HEART OF DOWNTOWN Honolulu lies a verdant twenty-acre public garden containing more than ten thousand species of trees and plants from around the world, a visible symbol of the fact that Hawai'i is a place of biological as well as cultural fusion. The donor of this botanical preserve was Mary Foster (1844-1930), whose life exemplified this fusion of Asian, Pacific, and Western peoples and cultures on this remote island chain. Scion of a wealthy family of Hawaiian and haole ancestry, Foster was one of a number of second- and third-generation Island residents who crossed the cultural boundaries that separated people in Hawai'i. By immersing themselves in syncretic religious movements such as Buddhism and Theosophy, they helped bridge cultural and ethnic divisions in Honolulu during this era and foreshadowed the ethnic and cultural mosaic that Hawai'i became later in the twentieth cen- tury. As a singular alliance of American businessmen, missionary descendants, and their local allies closed in around a weakened monarchy in the early 1890s, seizing control of the economic and political destiny of Hawai'i, a handful of the kama'aina1 elite, among them Mary Foster, abandoned the Christian Protestant creeds of their parents and peers and turned instead to Asian and syncretic religions. Foster and her associates in this move were the predecessors of today's culturally integrated Hawai'i. Yet in their own time they were a tiny minority with little apparent influence. Is there a connection Frank J. -

Karma and Reincarnation

KARMA AND REINCARNATION A COLLATION FROM THE WRITINGS OF HELENA P. BLAVATSKY KARMA AND REINCARNATION Contents KARMIC CYCLES ............................................................................... 1 LAW OF HARMONY AND EQUILIBRIUM .............................................. 3 KARMA AND REINCARNATION .......................................................... 5 KARMA AND THE EGO ....................................................................... 7 THE EGO AFTER DEATH .................................................................. 10 KARMA AND THE SKANDHAS .......................................................... 12 LAW OF RETRIBUTION ..................................................................... 13 DISTRIBUTIVE KARMA .................................................................... 14 REFERENCES ................................................................................... 17 THEOSOPHICAL LITERATURE ........................................................... 18 Scanned from the original, February 2020, United Lodge of Theosophists, UK. KARMA AND REINCARNATION FROM THE WRITINGS OF HELENA BLAVATSKY E consider Karma as the Ultimate Law of the Universe, the source, W origin and fount of all other laws which exist throughout Nature. Karma is the unerring law which adjusts effect to cause, on the physical, mental and spiritual planes of being. As no cause remains without its due effect from greatest to least, from a cosmic disturbance down to the movement of your hand, and as like produces like, Karma is that unseen -

Alice Bailey Talks Talk to Arcane School Students Given on Friday, March 19, 1943

Alice Bailey Talks Talk to Arcane School students given on Friday, March 19, 1943 When we first came to New York in 1921 I started a Secret Doctrine class, and it was quite successful, but largely because Mr. Richard Prater, a personal pupil of HPB [Helena Blavatsky], who himself had a Secret Doctrine class, came into my class and listened to what I had to say and then turned his whole class into mine. Shortly before he died he gave me the esoteric instructions that still go out to the Esoteric Section of the Theosophical Society. I found in it a great deal on the Antahkarana. It is the more personal part of the writing that interested me this morning. Two things stick out. The first was that HPB bitterly regretted having ever mentioned the Masters, and in this I think she was wrong. She very much felt that she had dragged their names in the dirt, that even the very best people, who wanted to follow them and tread the path, didn’t understand; with the result that in the Theosophical Society you have an approach to the Masters that I think is deplorable. It is an approach of complete devotion. It takes the disciple to the feet of the Master, and there he sits and expects the Master to solve his problems, to solve his karma for him. As one of the Masters says in the Mahatma Letters , such clouds of thoughtforms of devotion have been built up between the Master and the disciple that it is impossible for the Master to reach the disciple. -

Annie Besant Née Wood Biography

Annie Besant, 1847–1933 ‘ Better remain silent, better not even think, if you are not prepared to act.’ — Annie Besant nnie Besant was a social reformer, activist, socialist, feminist, PhotograPhic Portrait of annie atheist-turned-theosophist, independent publisher, writer, advocate Besant used in her autoBiogra- for Irish home rule and Indian independence leader—she was a busy Phy, conway hall collections woman. She was born Annie Wood in London, to a middle class family of Irish descent. Her father died when she was five years old, leaving the family financially unstable, so Annie was sent to live with a family friend, Ellen Marryat. Marryat ensured that Annie received a thorough education, teaching her a broad variety of subjects and encouraging her to think critically and to not underestimate her abilities as a woman. Marryat was also de- voutly religious—Besant described her as a fanatic—and Besant was made to study the Bible A and Foxes Book of Martyrs closely ; this evangelical education, whilst encouraging Besant’s later atheism, also likely inspired her intense sense of social duty. In 1867, she married the clergyman Frank Besant and they had two children, thought the marriage ended in 1873, due to her increas- ingly anti-religious views. Following her separation, Besant became closely associated with Charles Bradlaugh and his newly- formed National Secular Society (NSS) and began co-editing Bradlaugh’s secularist journal, The National Reformer. In 1877, Annie Besant was sent to court, alongside Bradlaugh, on obscenity charges for establishing the Freethought Publishing Company in order to republish an instructive birth control pamphlet, Fruits of Philosophy.