About the Authors

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Submitied in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree Of

AN EXAMINATION OF THE SUITABILITY OF SOME CONTEMPORARY SOUTH AFRICAN FICTION FOR READERS IN THE POST·DEVELOPMENTAL READING STAGE HALF·THESIS SUBMITIED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF EDUCATION OF RHODES UNIVERSITY by LORNA COLE DECEMBER 1991 TABLE OF CONTENTS (ii) Page Acknowledgements (iv) Abstract (v) Introduction (vii) Research Methodology (x) CHAPTER 1: READERS IN THE POST-DEVELOPMENTAL READING STAGE 1.1 A definition. 1 1.2 Characteristic requirements of readers in the post-developmental reading stage:- 5 1.2.1 Length of book 5 1.2.2 Abstract thinking and its implications 7 1.2.3 Searching for a sense of identity 10 1.2.4 Fantasy or reality? 12 1.3 A justification for the publishing of literature written specifically for children in the post-developmental reading stage. 23 1.4 South African literature for readers in the post-developmental reading stage. 29 1.5 Evaluation of the literature: Adults' or childrens' standards? 34 CHAPTER 2: A CRITICAL EVALUATION OF SOME INDIGENOUS WORKS OF FANTASY FOR CHILDREN IN THE IMMEDIATE POST-DEVELOPMENTAL READING STAGE: MARGUERITE POLAND'S THE MANTIS AND THE MOON AND ONCE AT KWA FUBESI 2.1 Introduction: Fantasy for the older child. 40 2.2 Marguerite Poland and indigenous oral literature. 44 2.3 The narrator and the "audience". 47 2.4 Settings. 49 2.5 Language and style. 53 2.6 Characters and characterisation. 58 2.7 Plots and themes. 62 2.8 Conclusion. 67 (iii) CHAPTER 3: CONTEMPORARY REALISM IN SOUTH AFRICAN FICTION: A CRITICAL EXAMINATION OF PIG BY PAUL GERAGHTY AND THE KAY ABOETIES BY ELANA BREGIN Page 3.1 Introduction : Contemporary realism and adolescence. -

Constructions of Identtiy in Marguerite Poland's

- CONSTRUCTIONS OF IDENTTIY IN MARGUERITE POLAND'S SHADES (1993) AND IRON LOVE (1999). By Mark Christopher Jacob Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in South African Literature and Language, University of Durban Westville, January 2003. SUPERVISOR: Professor Lindy Stiebel / / I DECLARATION The Registrar (Academic) UNNERSIlY OF DURBAN-WESTVILLE Dear Sir I, MARK CHRISTOPHER JACOB REG. NO: 200202011 hereby declare that the dissertation/thesis entitled "Constructions of identity in Marguerite Poland's novels, Shades (1993) and Iron Love (1999)" is the result of my own investigation and research and that it has not been submitted in part or in full for any other degree or to any other University. ----~~----- 19.Q~_:£~:_~__ (Date) ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS A great many people have helped me with advice, information and encouragement in the writing and compilation of this thesis. In particular, I would like to thank: ~ Dr. Marguerite Poland, for her inspiration and for taking time off from her busy schedule to shed light on important issues in her novels ~ My supervisor, Professor Lindy Stiebel, for her time, knowledge, encouragement and insightful comments ~ My parents and family members, especially Lynn, Valencia, Blaise and Maxine for their practical assistance, patience and support ~ My friends and colleagues for their support and encouragement ~ The National Research Foundation for their financial assistance towards this research. Opinions expressed in this thesis and conclusions arrived at are those of the author and are not necessarily to be attributed to the National Research Foundation ~ My' shades' for inspiration and direction in life. ABSTRACT Constructions of Identity in Marguerite Poland's novels, Shades (1993) and Iron Love (1999) In this thesis I will examine Marguerite Poland's two novels, Shades (1993) and Iron Love (1999) in terms of how they provide constructions of identity in a particular milieu and at a particular time. -

A Critique of English Setwork Selection (2009-2011)

TRADITION OR TRANSFORMATION: A CRITIQUE OF ENGLISH SETWORK SELECTION (2009-2011) Rosemary Ann Silverthorne A Research Report submitted to the Faculty of the Humanities, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in English Education. Johannesburg 2009. i Abstract This Research Report critiques the English Home Language Literature setwork selection for the period 2009-2011 in terms of the National Curriculum Statement for English Home Language for Grades 10- 12 to establish whether there is consonance between policy and practice in this section of the syllabus and to determine whether the new national syllabus offers a traditional or a transformational approach to the subject. In order to do this, the National Curriculum Statement is analysed in terms of the principles and outcomes which it intends to be actualised in the study of English and selects those that seem applicable to literature studies. Questions are formulated encapsulating these principles and used as the tools to critique the new national literature syllabus both as regards its individual constituent parts and as regards the syllabus as a whole. A brief comparison between the current prescribed literature selection and setworks set from 1942 to the present day establishes whether the new syllabus has departed from old syllabus designs, whether it acknowledges the new target group of pupils in multiracial English Home Language classrooms by offering a revised, wider and more inclusive selection of novels, dramas, poems and other genres such as short stories, or whether it remains traditionally Anglocentric in conception. The conclusions reached are that although the setworks conform to the letter of the requirements set down in the NCS, the underlying spirit of transformation is not realised. -

1 South African Great War Poetry 1914-1918: a Literary

1 SOUTH AFRICAN GREAT WAR POETRY 1914-1918: A LITERARY- HISTORIOGRAPHICAL ANALYSIS by GERHARD GENIS submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF LITERATURE AND PHILOSOPHY in the subject ENGLISH at the UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH AFRICA PROMOTER: DOCTOR J. PRIDMORE JANUARY 2014 2 I declare that SOUTH AFRICAN GREAT WAR POETRY 1914-1918: A LITERARY-HISTORIOGRAPHICAL ANALYSIS is my own work and that all the sources that I have used or quoted have been indicated and acknowledged by means of complete references. ________________________________ ___________________ 3 DEDICATION To my wife Regina, who had to keep the homefire burning while I was in the trenches. To my two daughters, Heidi and Meleri. To my mother Linda, whose love of history and literature has been infectious. To my sister Deidre and brothers Pieter and Frans. To my father Pieter, and brother-in-law Gerhard – R.I.P. To all those who served in the Great War. 4 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am happy to acknowledge the indispensable assistance that I received in completing this thesis. I was undecided on a topic when I visited Prof. Ivan Rabinowitz, formerly of the University of South Africa. He suggested this unexplored and fascinating topic, and the rest is history... I want to thank Dr July Pridmore, my promoter, and Prof. Deirdre Byrne from the Department of English Studies for their constructive feedback and professional assistance. The University of South Africa considerably lessened the financial burden by awarding me a Postgraduate Bursary for 2012 and 2013. Dawie Malan, the English subject librarian, was always available to lend a hand to locate relevant sources. -

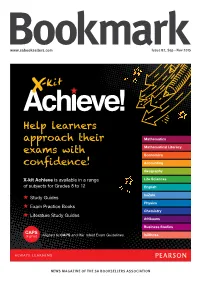

Help Learners Approach Their Exams with Confidence!

www.sabooksellers.com Issue 82, Sep – Nov 2015 Help learners Mathematics approach their Mathematical Literacy exams with Economics Accounting c o n fi d e n c e ! Geography X-kit Achieve is available in a range Life Sciences of subjects for Grades 8 to 12 English IsiZulu Study Guides Physics Exam Practice Books Chemistry Literature Study Guides Afrikaans Business Studies Aligned to CAPS and the latest Exam Guidelines. IsiXhosa NEWS MAGAZINE OF THE SA BOOKSELLERS AssOCIATION Contents The AGM report issue REGULARS GENERAL TRADE 4 • S A Booksellers National Executive • Bookmark 10 General trade sector Annual report week 1–26 2015 • SA Booksellers Association LIBRARIES 6 President’s Letter 12 Open Book Festival 29 Member Listing Here to stay 23 Library report SA Booksellers AGM 2015 E-BOOKS 14 Breyten Breytenbach Festival Honoring a great man 24 World Library Congress 7 Digital sector Librarians of the world descend on Annual report August 2014 – July 2015 16 Celebrating brilliance Cape Town The Sefika Awards 8 Understanding e-commerce EDUCATION AND ACADEMIC enabled websites 18 SA National Book Week A useful tool for customer and seller #GoingPlaces 25 Education sector Annual report August 2014 – July 2015 9 Footnote Summit 2015 20 Generation after generation Tech and the publisher in this Adams and 150 years of trading 26 Academic sector Annual report August 2014 – July 2015 new world 22 Ontsluit Afrikaans van die toekoms 28 African Education Week Die HAT vier mylpaal met sesde uitgawe A world of educational knowledge Study Guides Exam Practice Books Literature Study Guides Step-by-step explanations, Full examination papers with Detailed summaries and analysis, worked examples and plenty complete memoranda. -

Alternation Article Template

Contributors Philip Onoriode Aghoghovwia is a graduate student of English at Stellenbosch University, South Africa. His PhD research is on ‘Oil Encounter, Niger Delta Literature, Nigerian Public(s), and the Rethinking of Ecocriticism within the Context of Environmental and Social Justice’. He is a graduate school scholarship holder at Stellenbosch University’s Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences. His most recent article appeared in Politics of the Postcolonial Text: Africa and its Diasporas published in Germany. He has presented papers on his on-going doctoral research at conferences, including the annual Ecology and Literature Colloquium, South Africa, the Cambridge/Africa Collaborative Research on African Literature, Nigeria, and the recently concluded ‘Petrocultures: Oil, Energy, and Cultures’ conference at the University of Alberta, Edmonton, Canada. Contact details: [email protected] Stephen Gray was born in Cape Town in 1941 and studied at the University of Cambridge, England, and the Iowa Writers’ Workshop. Until 1992 he taught English in what nowadays is the University of Johannesburg, where he is retired and holds an emeritus status. His doctorate there became Southern African Literature: An Introduction (1979). He has since published many creative works and is collecting material on the Atlantic Islands. Contact details: P.O. Box 2633, Houghton, 2041 Pat Louw teaches English at the University of Zululand, South Africa. Apart from her research on Doris Lessing’s African writings, she is interested in notions of landscape, place and ecocriticism. She has organized two Literature & Ecology conferences, and has edited a special edition of Alternation. Other publications include work on Dalene Matthee, Thomas Alternation Special Edition 6 (2013) 235 - 239 235 ISSN 1023-1757 Contributors Hardy, Marguerite Poland and Chris Mann as well as an article on wild life documentaries. -

Bagpipe 2009.Pmd

2008 to 2009 No. 31 Calls via email for contributions have again elicited an overwhelming response. Mac is grateful to all who contributed. Keep the information rolling in! Mac has had to wield the editorial pen with considerable vigour (not to mention ruthlessness), however, as the printed version of the Bagpipe is necessarily limited by postage costs. Fuller versions of a number of the contributions appear on the OA website: www.oldandrean.com. Where the contributions have been significantly shortened, the symbol ¶ precedes the contribution. Some (marked ¶¶) have been radically shortened: it is worth making the effort to read the full accounts.) Modge Walter (U4043) gets the ball rolling (Mac: or them while they were in Malaysia and Singapore and managed should that be the bagpipe playing?): As a retired couple, short trips to Thailand, China (my birthplace) and Sarawak both now in our eighties, we still seem to live a fairly active life whilst out in the Far East. This time we will be travelling via and continue to be thankful that we chose to retire to Port Halifax where my sister Alicia (an old DSG girl), now widowed, Elizabeth some twenty-five years ago. [This was after 36 years lives. as an electrical engineer and senior manager with Escom in ¶¶ Duncan Strachan ( M4545) writes: I returned to Natal and the Transvaal and after my retirement I was asked my home in Kenya, from College, just as WW2 was coming to serve as a Technical Consultant for Escom here in Port to an end. We flew from Grahamstown to Johannesburg, from Elizabeth for the Kwanabuhle electrification project.] there to some God-forsaken airfield in central Africa for the We are both active in our church – St John’s (Anglican) night, and then on to Nairobi - it took three days of flying in Church here in Walmer – as Lay ministers although I have an 18 seater Avro Anson, and it was at Mtito-Andei (probably partly retired from serving during the services and restrict my spelled incorrectly; and referred to as “God-forsaken” above) serving to visiting and ministering to ‘Shut in” members. -

Literary Tourism As a Developing Genre: South Africa’S Potential

LITERARY TOURISM AS A DEVELOPING GENRE: SOUTH AFRICA’S POTENTIAL by YVONNE SMITH Submitted as full requirement for the degree MAGISTER HEREDITATIS CULTURAEQUE SCIENTIAE (HERITAGE AND CULTURAL TOURISM) in the Department of Historical and Heritage Studies Faculty of Humanities University of Pretoria Pretoria 2012 Supervisor: Prof. Karen L. Harris Co-supervisor: Mr Patrick Lenahan © University of Pretoria CONTENT PAGE List of Tables iv List of Figures v List of Appendices vi List of Abbreviations vii Acknowledgements viii Summary ix Chapter 1 Introduction 1 Chapter 2 Defining literary tourism 4 2.1 Literary tourism as cultural and heritage tourism 4 2.2 The literary realm: text, landscape and literature 9 2.3 Approaches to the study of literary tourism 13 Chapter 3 The consumers of literary heritage and culture 24 3.1 The power of creative literature 24 3.2 Literary tourists 26 3.3 Literary pilgrims and general literary tourists 33 Chapter 4 Characteristics of literary tourism attractions 42 4.1 The preservation, celebration and creation of literature 43 4.2 The birth, life and death of the author 45 4.3 Touring fiction 51 Chapter 5 History and development of literary tourism 59 5.1 Early modern literary tourism 59 5.2 Literary tourism in the Romantic era 65 5.3 From grand tourist to exotic African explorer 77 5.4 Southern African sightseeing through a literary lens 82 Chapter 6 Literary tourism in South Africa 91 6.1 Groot-Marico and Pelindaba 95 6.2 The Western Cape, Richmond and Kimberley 99 6.3 Bloemfontein and the Grahamstown region -

Rhodes Newsletter

RHODES NEWSLETTER Old Rhodian Union December, 1984 V___________________________ __________________________________________________________________J University of California Chancellor revisits alma mater Possibly our most illustrious alumnus, Professor John Saunders (1920) revisited Rhodes in October on holiday from San Francisco where he is Chancellor of the mammoth University of California. He was accompanied by his wife of eight years, Rose-bud. Both widowed, they had lived in the same street for many years. “He preferred the view from my house”, says Rose-bud. Professor Saunders went to California as head of the medical faculty before the Second World War. Not only is he ex tremely interesting when talking about the development of education in the USA, but he also has a faultless memory for people and events in Grahamstown more than sixty years ago. His father The Centenary of the Grahamstown — was in charge of Prince Alfred Hospital, Bad news for M C P'S Port Alfred train service was celebrated and their family home was “The Oaks”, in September when almost 600 people now demolished, up near the Vice- as women sweep toset off in Edwardian garb for a steam Chancellor’s Lodge. Professor Saunders train outing filled with beauty and came to Rhodes for the first time as a 13 power at Rhodes nostalgia. Pipe bands, bunting and year old to study Greek under Professor mayors in chains were the order of the Bowles. It was good having you backSince the recent election of a female day, plus a picnic champagne lunch at again, Professor Saunders. SRC president at Rhodes, women have Bathurst. Among the guests was Prime swept to leadership positions in a large Time presenter Dorianne Berry, seen number of the more prominent societies, here talking to our splendid archetypal committees and cluhs on the campus. -

Profile for Dr Marguerite Poland an Alumna of Rhodes University, Dr Marguerite Poland Is a Prolific Author and Writer of Fiction and Nonfiction Works

Profile for Dr Marguerite Poland An alumna of Rhodes University, Dr Marguerite Poland is a prolific author and writer of fiction and nonfiction works. Over the years, she has enriched the nation’s literary landscape with excellent works, which draw on the diverse South African experience. Born in Johannesburg in 1950, Dr Poland became one of the first 4th generation students to enrol at Rhodes University in 1968 and her great-grandfather Reverend AW Brereton was the first Registrar of Rhodes University. She received her BA, majoring in Xhosa and Social Anthropology, from Rhodes University in 1970, completed her Honours in Xhosa at Stellenbosch University and attained both her Masters and Doctoral degrees in Zulu Literature from the University of KwaZulu-Natal. Dr Poland was the first recipient of the Fitzpatrick Literary Award for Children’s Literature in 1979 for her tale The Mantis and the Moon, which she received again in 1983 for The Woodash Stars. In 1989, The Mantis and the Moon received a Sankei Honourable Award for translation into Japanese. Over the years, she has written eleven children’s books, many of which draw metaphorically on the African tradition without the retelling of folktales. Fluent in isiXhosa and isiZulu, much of Dr Poland's work reflects her interest in African culture with some of her children's stories in particular inspired by African oral traditions. Recessional for Grace is a novel which grew out of Dr Poland’s research for her doctoral thesis in Zulu Literature on the metaphoric naming of colour-patterns for Nguni cattle. Her book The Abundant Herds: a Celebration of the Cattle of the Zulu People is an adaptation of her PhD dissertation. -

University of Cape Town (UCT) in Terms of the Non-Exclusive License Granted to UCT by the Author

“Wars are won by men not weapons”: The invention of a militarised British settler identity in the Eastern Cape c. 1910–1965 Georgina Ovenstone (ovngeo001) A dissertation submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree of Master of Arts in Historical Studies Supervisor: Lance Van Sittert Co-supervisor: Sean Field Faculty of the Humanities UniversityUniversity of of Cape Cape Town Town 2019 The copyright of this thesis vests in the author. No quotation from it or information derived from it is to be published without full acknowledgement of the source. The thesis is to be used for private study or non- commercial research purposes only. Published by the University of Cape Town (UCT) in terms of the non-exclusive license granted to UCT by the author. University of Cape Town Compulsory Declaration This work has not been previously submitted in whole, or in part, for the award of any degree. It is my own work. Each significant contribution to, and question in, this dissertation from the work, or works, of other people has been attributed, and has been cited and referenced. Signature: Date: 21 November 2019 Acknowledgements No historian can find the treasures that exist in archives and libraries without the assistance of these treasures’ custodians. I wish to thank the many librarians who assisted me over the course of my research process. I would like specifically to record my gratitude to the staff of the Special Collections library at the University of Cape Town, especially Beverly Angus; the staff of the 1820 Settlers’ Memorial Museum, especially Gcobisa Zomelele; and the staff of the National Library of South Africa in Cape Town. -

Marguerite Poland's Landscapes As Sites for Identity Construction By

MARGUERITE POLAND’S LANDSCAPES AS SITES FOR IDENTITY CONSTRUCTION BY MARK CHRISTOPHER JACOB Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in the Department of English UNIVERSITY OF KWAZULU-NATAL DURBAN 2008 ii ABSTRACT In this dissertation I focus on the life and works of Marguerite Poland and argue that landscapes in her fiction act as sites for identity construction. In my analysis I examine the central characters’ engagement with the land, taking cognisance of Poland’s historical context and that of her fiction as represented in her four adult novels and eleven children’s books. I also focus on her doctoral thesis and non-fiction work, The Abundant Herds: A Celebration of the Nguni Cattle of the Zulu People (2003). Poland’s latest work The Boy In You (2008) appeared as this thesis was being completed, thus I only briefly refer to this work in the Conclusion. My primary aim puts into perspective personal, social and cultural identities that are constructed through an analysis of the landscapes evident in her work. Post-colonial theories of space and place provide the theoretical framework. In summary, this thesis argues that landscape is central to Poland’s oeuvre, that her construction of landscape takes particular forms depending on the type of writing she undertakes; and that her characters’ construction of identity is closely linked to the landscapes in which they are placed by their author, herself a product of her physical and cultural environment. “Landscape is dynamic; it serves to create and naturalise the histories and identities inscribed upon it, and so simultaneously hides and makes evident social and historical formations” (Carter et al 1993: xii).