Download Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Culmination of Tradition-Based Tafsīr the Qurʼān Exegesis Al-Durr Al-Manthūr of Al-Suyūṭī (D. 911/1505)

The Culmination of Tradition-based Tafsīr The Qurʼān Exegesis al-Durr al-manthūr of al-Suyūṭī (d. 911/1505) by Shabir Ally A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Near and Middle Eastern Civilizations University of Toronto © Copyright by Shabir Ally 2012 The Culmination of Tradition-based Tafsīr The Qurʼān Exegesis al-Durr al-manthūr of al-Suyūṭī (d. 911/1505) Shabir Ally Doctor of Philosophy Department of Near and Middle Eastern Civilizations University of Toronto 2012 Abstract This is a study of Jalāl al-Dīn al-Suyūṭī’s al-Durr al-manthūr fi-l-tafsīr bi-l- ma’thur (The scattered pearls of tradition-based exegesis), hereinafter al-Durr. In the present study, the distinctiveness of al-Durr becomes evident in comparison with the tafsīrs of al- a arī (d. 310/923) and I n Kathīr (d. 774/1373). Al-Suyūṭī surpassed these exegetes by relying entirely on ḥadīth (tradition). Al-Suyūṭī rarely offers a comment of his own. Thus, in terms of its formal features, al-Durr is the culmination of tradition- based exegesis (tafsīr bi-l-ma’thūr). This study also shows that al-Suyūṭī intended in al-Durr to subtly challenge the tradition- ased hermeneutics of I n Taymīyah (d. 728/1328). According to Ibn Taymīyah, the true, unified, interpretation of the Qurʼān must be sought in the Qurʼān ii itself, in the traditions of Muḥammad, and in the exegeses of the earliest Muslims. Moreover, I n Taymīyah strongly denounced opinion-based exegesis (tafsīr bi-l-ra’y). -

Public Notice Auction of Gold Ornament & Valuables

PUBLIC NOTICE AUCTION OF GOLD ORNAMENT & VALUABLES Finance facilities were extended by JS Bank Limited to its customers mentioned below against the security of deposit and pledge of Gold ornaments/valuables. The customers have neglected and failed to repay the finances extended to them by JS Bank Limited along with the mark-up thereon. The current outstanding liability of such customers is mentioned below. Notice is hereby given to the under mentioned customers that if payment of the entire outstanding amount of finance along with mark-up is not made by them to JS Bank Limited within 15 days of the publication of this notice, JS Bank Limited shall auction the Gold ornaments/valuables after issuing public notice regarding the date and time of the public auction and the proceeds realized from such auction shall be applied towards the outstanding amount due and payable by the customers to JS Bank Limited. No further public notice shall be issued to call upon the customers to make payment of the outstanding amounts due and payable to JS Bank as mentioned hereunder: Customer ID Customer Name Address Amount as of 8th April 1038553 ZAHID HUSSAIN MUHALLA MASANDPURSHI KARPUR SHIKARPUR 343283.35 1012051 ZEESHAN ALI HYDERI MUHALLA SHIKA RPUR SHIKARPUR PK SHIKARPUR 409988.71 1008854 NANIK RAM VILLAGE JARWAR PSOT OFFICE JARWAR GHOTKI 65110 PAK SITAN GHOTKI 608446.89 999474 DARYA KHAN THENDA PO HABIB KOT TALUKA LAKHI DISTRICT SHIKARPU R 781000 SHIKARPUR PAKISTAN SHIKARPUR 361156.69 352105 ABDUL JABBAR FAZALEELAHI ESTATE S HOP NO C12 BLOCK 3 SAADI TOWN -

Sindh Coast: a Marvel of Nature

Disclaimer: This ‘Sindh Coast: A marvel of nature – An Ecotourism Guidebook’ was made possible with support from the American people delivered through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). The contents are the responsibility of IUCN Pakistan and do not necessarily reflect the opinion of USAID or the U.S. Government. Published by IUCN Pakistan Copyright © 2017 International Union for Conservation of Nature. Citation is encouraged. Reproduction and/or translation of this publication for educational or other non-commercial purposes is authorised without prior written permission from IUCN Pakistan, provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of this publication for resale or other commercial purposes is prohibited without prior written permission from IUCN Pakistan. Author Nadir Ali Shah Co-Author and Technical Review Naveed Ali Soomro Review and Editing Ruxshin Dinshaw, IUCN Pakistan Danish Rashdi, IUCN Pakistan Photographs IUCN, Zahoor Salmi Naveed Ali Soomro, IUCN Pakistan Designe Azhar Saeed, IUCN Pakistan Printed VM Printer (Pvt.) Ltd. Table of Contents Chapter-1: Overview of Ecotourism and Chapter-4: Ecotourism at Cape Monze ....... 18 Sindh Coast .................................................... 02 4.1 Overview of Cape Monze ........................ 18 1.1 Understanding ecotourism...................... 02 4.2 Accessibility and key ecotourism 1.2 Key principles of ecotourism................... 03 destinations ............................................. 18 1.3 Main concepts in ecotourism ................. -

Muslim Saints of South Asia

MUSLIM SAINTS OF SOUTH ASIA This book studies the veneration practices and rituals of the Muslim saints. It outlines the principle trends of the main Sufi orders in India, the profiles and teachings of the famous and less well-known saints, and the development of pilgrimage to their tombs in India, Pakistan and Bangladesh. A detailed discussion of the interaction of the Hindu mystic tradition and Sufism shows the polarity between the rigidity of the orthodox and the flexibility of the popular Islam in South Asia. Treating the cult of saints as a universal and all pervading phenomenon embracing the life of the region in all its aspects, the analysis includes politics, social and family life, interpersonal relations, gender problems and national psyche. The author uses a multidimen- sional approach to the subject: a historical, religious and literary analysis of sources is combined with an anthropological study of the rites and rituals of the veneration of the shrines and the description of the architecture of the tombs. Anna Suvorova is Head of Department of Asian Literatures at the Institute of Oriental Studies, Russian Academy of Sciences, Moscow. A recognized scholar in the field of Indo-Islamic culture and liter- ature, she frequently lectures at universities all over the world. She is the author of several books in Russian and English including The Poetics of Urdu Dastaan; The Sources of the New Indian Drama; The Quest for Theatre: the twentieth century drama in India and Pakistan; Nostalgia for Lucknow and Masnawi: a study of Urdu romance. She has also translated several books on pre-modern Urdu prose into Russian. -

List of Rejected Candidates for Website.Pdf

LIST OF REJECTED CANDIDTES FOR SCHOOL EDUCATION SCHOLARSHIP PROGRAM 2019-2020 No Position Applicant Name Father Name CNIC Contact Rejection Type Rejection Reason 1 6TH Class ABDUL BARI LAKHA DINO 41301-5082355-1 0307-3423289 Academic NOT ELIGIBLE ACCORDING TO ADVERTISEMENT 2 6TH Class AMBREEN HAZOOR BUX 45101-3916208-9 0301-2370449 Professional DUE TO STUDYING IN PRIVATE SCHOOL 3 6TH Class BASHER AHMED AHMED ALI 43101-6840946-9 0345-3761966 Academic NOT ELIGIBLE ACCORDING TO ADVERTISEMENT. 4 6TH Class ZEESHAN AHMED ALI 43101-6840946-9 0340-1106766 Academic NOT ELIGIBLE ACCORDING TO ADVERTISEMENT 6TH Class ALI DINO LATE HAZOOR BUX 45504-3706967-1 0305-3660054 Academic NOT COMPLETING THE REQUIREMENTS BECAUSE HE IS 5 CURRENTLY STUDYING IN 8TH CLASS 6 6TH Class ABDUL AZIZ GULSHAN KHAN 45202-0677294-9 0302-3626040 Academic STUDYING IN CLASS 8TH CLASS 7 6TH Class ZAMUR HUSSAIN LATE HAZOOR BUX 00000-0000000-0 0305-3660054 Academic NOT ELIGIBLE ACCORDING TO ADVERTISEMENT 8 6TH Class MISBAH BATOOL INAM ALI 43302-8483127-1 0302-3683818 Professional DUE TO PRIVATE SCHOOL 9 6TH Class ABDUL QADEER NASEEM HUSSAIN 43407-0350673-1 0300-3480216 Academic CURRENTLY STUDYING IN 7TH CLASS 10 6TH Class SANA BATOOL INAM ALI 43302-8483127-1 0302-3683818 Academic PRIVATE SCHOOL 11 6TH Class SUHAIL AHMED AHMED ALI 43101-6840946-9 0345-3761966 Academic NOT ELIGIBLE ACCORDING TO ADVERTISEMENT 12 6TH Class ASIF ALI HAJI MALHAR 45104-0271114-9 0309-3449012 Professional DUE TO PRIVATE SCHOOL 13 6TH Class ALTAF MEHBOOB ALI 45302-8595148-1 0302-3603005 Academic NOT ELIGIBLE -

Religio-Political Movements in the Pashtun Belt-The Roshnites

Journal of Political Studies, Vol. 18, Issue - 2, 2011: 119-132 Religio-Political Movements in the Pashtun Belt-The Roshnites Zahid Shah∗ Abstract The Pashtun belt, encompassing chiefly Eastern Afghanistan and North Western Pakistan, has been, and continues to be, the center of religio-political activity. This article aims at examining these activities in its historical perspectives and has focused on one of the earliest known Movements that sprouted in the region. The first known indigenous religio-political movement of high magnitude started in the area was the Roshnite struggle against 16th century Mughal India. The Movement originated in Mehsud Waziristan (forming part of contemporary tribal areas of Pakistan) and spread into the whole Pashtun regions. Initially aimed at doctrinal reformation, the Movement finally assumed a political character. The leader proclaimed his followers as rightly guided and the non- conformist as outcasts. This resulted in a controversy of high order. The Pashtun society was rent apart and daggers drawn. Hostile Pashtun factions first engaged in acrimony and polemics and eventually began killing in battle-fields. The story of the feuds of this period spreads over more or less a century. The leader of the movement, a religious and mystical practitioner, had a great charm to attract and transform people, but the movement at present times has little tracing. Besides the leader, the chief proponents of the movement were men endowed with literary and intellectual acumen. The combined efforts of the leader and his followers and also the forceful counter-reactionary movement, have enriched Pashtun language and lore. The literature produced during this period presents an interesting reading of the Pashtun history of this time. -

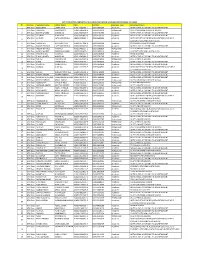

List of Trainees of Egp Training

Consultancy Services for “e-GP Related Training” Digitizing Implementation Monitoring and Public Procurement Project (DIMAPPP) Contract Package # CPTU/S-03 Central Procurement Technical Unit (CPTU), IMED Ministry of Planning Training Time Duration: 1st July 2020- 30th June 2021 Summary of Participants # Type of Training No. of Participants 1 Procuring Entity (PE) 876 2 Registered Tenderer (RT) 1593 3 Organization Admin (OA) 59 4 Registered Bank User (RB) 29 Total 2557 Consultancy Services for “e-GP Related Training” Digitizing Implementation Monitoring and Public Procurement Project (DIMAPPP) Contract Package # CPTU/S-03 Central Procurement Technical Unit (CPTU), IMED Ministry of Planning Training Time Duration: 1st July 2020- 30th June 2021 Number of Procuring Entity (PE) Participants: 876 # Name Designation Organization Organization Address 1 Auliullah Sub-Technical Officer National University, Board Board Bazar, Gazipur 2 Md. Mominul Islam Director (ICT) National University Board Bazar, Gazipur 3 Md. Mizanoor Rahman Executive Engineer National University Board Bazar, Gazipur 4 Md. Zillur Rahman Assistant Maintenance Engineer National University Board Bazar, Gazipur 5 Md Rafiqul Islam Sub Assistant Engineer National University Board Bazar, Gazipur 6 Mohammad Noor Hossain System Analyst National University Board Bazar, Gazipur 7 Md. Anisur Rahman Programmer Ministry Of Land Bangladesh Secretariat Dhaka-999 8 Sanjib Kumar Debnath Deputy Director Ministry Of Land Bangladesh Secretariat Dhaka-1000 9 Mohammad Rashedul Alam Joint Director Bangladesh Rural Development Board 5,Kawranbazar, Palli Bhaban, Dhaka-1215 10 Md. Enamul Haque Assistant Director(Construction) Bangladesh Rural Development Board 5,Kawranbazar, Palli Bhaban, Dhaka-1215 11 Nazneen Khanam Deputy Director Bangladesh Rural Development Board 5,Kawranbazar, Palli Bhaban, Dhaka-1215 12 Md. -

GLIMPSES of the GOD-MAN MEHER BABA Volume 1 (1943-1948)

GLIMPSES OF THE GOD-MAN MEHER BABA Volume 1 (1943-1948) By Bal Natu An Avatar Meher Baba Trust eBook June 2011 Copyright © 1977 by Bal Natu Source: This eBook reproduces the original edition of Glimpses of the God-Man, Meher Baba, Volume1, published by Sufism Reoriented (Walnut Creek, California) in 1977. eBooks at the Avatar Meher Baba Trust Web Site The Avatar Meher Baba Trust’s eBooks aspire to be textually exact though non-facsimile reproductions of published books, journals and articles. With the consent of the copyright holders, these online editions are being made available through the Avatar Meher Baba Trust’s web site, for the research needs of Meher Baba’s lovers and the general public around the world. Again, the eBooks reproduce the text, though not the exact visual likeness, of the original publications. They have been created through a process of scanning the original pages, running these scans through optical character recognition (OCR) software, reflowing the new text, and proofreading it. Except in rare cases where we specify otherwise, the texts that you will find here correspond, page for page, with those of the original publications: in other words, page citations reliably correspond to those of the source books. But in other respects—such as lineation and font—the page designs differ. Our purpose is to provide digital texts that are more readily downloadable and searchable than photo facsimile images of the originals would have been. Moreover, they are often much more readable, especially in the case of older books, whose discoloration and deteriorated condition often makes them partly illegible. -

Bayazid Ansari and Roushaniya Movement: a Conservative Cult Or a Nationalist Endeavor?

Himayatullah Yaqubi BAYAZID ANSARI AND ROUSHANIYA MOVEMENT: A CONSERVATIVE CULT OR A NATIONALIST ENDEAVOR? This paper deals with the emergence of Bayazid Ansari and his Roushaniya Movement in the middle of the 16th century in the north-western Pakhtun borderland. The purpose of the paper is to make comprehensive analyses of whether the movement was a militant cult or a struggle for the unification of all the Pakhtun tribes? The movement initially adopted an anti- Mughal stance but side by side it brought stratifications and divisions in the society. While taking a relatively progressive and nationalist stance, a number of historians often overlooked some of its conservative and militant aspects. Particularly the religious ideas of Bayazid Ansari are to be analyzed for ascertaining that whether the movement was nationalist in nature and contents or otherwise? The political and Sufi orientation of Bayazid was different from the established orders prevailing at that time among the Pakhtuns. An attempt would be made in the paper to ascertain as how much support he extracted from different tribes in the Pakhtun region. From the time of Mughal Emperor Babur down to Aurangzeb, the whole of the trans-Indus Frontier region, including the plain and the hilly tracts was beyond the effective control of the Mughal authority. The most these rulers, including Sher Shah, himself a Ghalji, did was no more than to secure the hilly passes for transportation. However, the Mughal rulers regarded the area not independent but subordinate to their imperial authority. In the geographical distribution, generally the area lay under the suzerainty of the Governor at Kabul, which was regarded a province of the Mughal Empire. -

The Real Face of Roshaniyya Movement

Fakhr-ul-Islam* Shahbaz Khan** The Real Face Of Roshaniyya Movement Abstract Bayazid Ansari, the founder of Roshaniyya Movement, was basically a mystic, who had some knowledge of Islam. He had originally initiated the Roshaniyya movement for spreading his teachings among the people, however, he almost everywhere faced resistance from the orthodox Ulama and saints. According to them Bayazid Ansari had deviated from the right path. As far as the term Roshaniyya is concerned it was due to the nickname of Bayazid Ansari as he was known by the name of Pir Roshan or Rokhan (the illuminated guide), As regard the true status of the Roshaniyya movement there exists difference of views, as to some people it was a religio-cum-Sufic movement while to others it was political in nature yet to another group of scholars Roshaniyya was a Pakhtun nationalist movement. This paper is an attempt to analyse the said issue in order to reach an understandable conclusion. Key Words: Bayazid Ansari, Roshaniyya Movement, Political, Nationalist, Sufi, Ulama Introduction Bayazid Ansari was born in the house of Abdullah, a religious scholar and a native of South Wazirista, in 1572.1 Although he had not received proper education yet he was a sharp minded and intelligent person.2 Bayazid, in childhood, witnessed problems including the Mughal invasion of India, separation between his parents and the ill-treatment of his step mother, which must have certainly affected his personality from the early childhood. As a child, he was in search of truth, who often asked questions like “The heavens and earth are here, but where is God,3 which indicates towards the fact that he was not an ordinary kid. -

Madrassas of Surma-Barak Valley

Chapter – III MADRASSAS OF SURMA-BARAK VALLEY Madrassa education is not a product of any historical event or occurrence but an in built system of Islam which worked for the spread of education among the Muslim through ages. According to some Muslim theologian madrassa education of modern form originated at Baghdad by Nizam ul-Mulk Tusi (the vizir or the Prime Minister) of Sultan Alp Arslan and the first Madrassa was „Madrassa-e-Nizamia‟ Baghdad established in 1067 A.D.1 But, available historical accounts show us about the existence of madrassa even before Nizam was born. Sultan Mahmud of Gazni build a mosque at Gazni in 1019 and also established a madrassa nearby the mosque. The scholars of eminence were employed to impart instructions in tafsir, hadith and fiqh.2 He too established a library and for the maintenances of the madrassa, mosque and library „waqf‟ (donated) certain area of land.3 Sultan Mahmud‟s also encouraged his nobles to start madrassas and accordingly they too started several madrassas in their respective areas. It may be mention here that Gazni was then an advance centre of Islamic education and was contemporary of Baghdad.4 In India, madrassa education began even before the Muslim rule and was started centering round mosque in the form of maqtab. Initially it was started by the Arabian traders in the Malabar Coast of South India in the last part of 7th century. The conquest of Sind by Muhammad Bin Qasim in eighth century further spread the same in India.5 However, madrassa education of formal form began in India during the Sultanate period. -

Religious and Social Reforms of Sufi-Saints in North Karnataka

Review Of ReseaRch impact factOR : 5.7631(Uif) UGc appROved JOURnal nO. 48514 issn: 2249-894X vOlUme - 8 | issUe - 2 | nOvembeR - 2018 __________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ RELIGIOUS AND SOCIAL REFORMS OF SUFI-SAINTS IN NORTH KARNATAKA Ajeed Mayar1 and Vijayakumar H. Satimani2 1Research Scholar , Department Of History , Gulbarga University , Gulbarga. 2Asst. Professor In History , Govt First Grade College , Chittapur. ABSTRACT Kamataka is a standout amongst the most imperative southern conditions of India. It has picked up conspicuousness politically, socio-monetarily, logically and in numerous other ways. It is a gathering spot of numerous religious rationalities and a liquefying point accomplishing the amalgamation of the instructing of numerous religious changes. Sufism is a spiritualist religion. It is a branch of Islam. Sufi holy people are the devotees of ALLAH and the act of harmony, consideration and resistance. They declared a religion dependent on the idea of affection, the adoration with the individual being and the love with a definitive or the maker. Sufi holy people and Sufism are a current reality in Indian socio-religious overlap and it has contributed for a solid and neighborly social request. It has prompt another social set-up brimming with qualities, and control. Sufism as a religion of the joining millions turned into the rehearsing framework among the general population of India and in addition Karnataka. This investigation of Sufi Saints in Karnataka is accordingly a propelled endeavor to depict this religion of the spirit and heart. Much accentuation is laid on the ideas and exceptional parts of Sufism, alongside different rehearses found in it. I was constantly pulled in by its otherworldly essentialness and viable substance and furthermore its significant impact on the overall population.