Carcharhinus Perezi.Pmd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sharks and Rays

SHARKS AND RAYS Photo by: © Jim Abernethy Transboundary Species - Content ... 31 32 33 34 35 ... Overview As stated in the previous section, the establishment of the Yarari fishing for sharks in the Netherlands and places new pressure on Marine Mammal and Shark Sanctuary was an important step fishermen to implement new techniques and updated fishing gear in protecting the shark and ray species of the Dutch Caribbean. to avoid accidentally catching sharks and rays as bycatch. Overall, there is a significant lack of information concerning these vital species within Dutch Caribbean waters. Fortunately, this There are several different international treaties and legisla- trend is changing and in the last few years there has been a push tion which offer protection to these species. This includes the to increase research, filling in the historic knowledge gap. Sharks Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES), and rays are difficult species to protect as they tend to have long the Specially Protected Areas and Wildlife (SPAW) protocol and reproduction cycles, varying between 3 and 30 years, small litters, the Convention on Migratory Species (CMS). Scientists are just which means they do not recover quickly when overfished and can beginning to uncover the complexities of managing conservation travel over great distances which makes them difficult to track. efforts for these species, as they often have long migration routes which put them in danger if international waters are not managed Early in 2019, the Ministry of Agriculture, Nature and Food Quality and protected equally. (LNV) published a strategy document to manage and protect sharks and rays within waters the Netherlands influences (this There are more than thirty different species of sharks and includes the North Sea, Dutch Caribbean and other international rays which are known to inhabit the waters around the Dutch waters). -

Elasmobranch Biodiversity, Conservation and Management Proceedings of the International Seminar and Workshop, Sabah, Malaysia, July 1997

The IUCN Species Survival Commission Elasmobranch Biodiversity, Conservation and Management Proceedings of the International Seminar and Workshop, Sabah, Malaysia, July 1997 Edited by Sarah L. Fowler, Tim M. Reed and Frances A. Dipper Occasional Paper of the IUCN Species Survival Commission No. 25 IUCN The World Conservation Union Donors to the SSC Conservation Communications Programme and Elasmobranch Biodiversity, Conservation and Management: Proceedings of the International Seminar and Workshop, Sabah, Malaysia, July 1997 The IUCN/Species Survival Commission is committed to communicate important species conservation information to natural resource managers, decision-makers and others whose actions affect the conservation of biodiversity. The SSC's Action Plans, Occasional Papers, newsletter Species and other publications are supported by a wide variety of generous donors including: The Sultanate of Oman established the Peter Scott IUCN/SSC Action Plan Fund in 1990. The Fund supports Action Plan development and implementation. To date, more than 80 grants have been made from the Fund to SSC Specialist Groups. The SSC is grateful to the Sultanate of Oman for its confidence in and support for species conservation worldwide. The Council of Agriculture (COA), Taiwan has awarded major grants to the SSC's Wildlife Trade Programme and Conservation Communications Programme. This support has enabled SSC to continue its valuable technical advisory service to the Parties to CITES as well as to the larger global conservation community. Among other responsibilities, the COA is in charge of matters concerning the designation and management of nature reserves, conservation of wildlife and their habitats, conservation of natural landscapes, coordination of law enforcement efforts as well as promotion of conservation education, research and international cooperation. -

Elasmobranchs in the Dutch Caribbean: Current Population Status, Fisheries, and Conservation

Elasmobranchs in the Dutch Caribbean: Current Population Status, Fisheries, and Conservation El Estado de Elasmobranquios y Medidas de la Pesca y Conservación en el Caribe Holandés Le Statut des Élasmobranches et Les Mesures de Peche et Conservation dans les AntillesNéerlandaises I.J.M. VAN BEEK*, A.O. DEBROT, and M. DE GRAAF IMARES, Wageningen University Research, P.O. Box 57, 1780 AB, Den Helder, The Netherlands. *[email protected]. ABSTRACT In the Dutch Caribbean EEZ, at least 27 elasmobranch species have been documented. Of these, nine are listed as “critically endangered” and eight as “near threatened” by the IUCN. Elasmobranchs are not a target fishery in the Dutch Caribbean, but do occur as bycatch in artisanal fisheries. Sharks are considered nuisance species by fishermen. Most sharks caught are not discarded, but consumed locally, used as bait, or (reportedly) killed and discarded at sea on the two islands where landing of sharks is illegal (Bonaire and St. Maarten). Based on recent data, published sport diver accounts, and anecdotal accounts, it is clear that shark populations in most areas of the Dutch Caribbean have been strongly depleted in the last half century. Two of the six islands have implemented regulation to protect sharks due to their ecological importance and economic value. Two other islands have implemented fish- and fisheries monitoring programmes. The fisheries monitoring includes port sampling with low numbers of shark landings, and on-board sampling with bycatch of sharks on each fishing trip. The fish monitoring has introduced the use of stereo-Baited Remote Underwater Video, a new method for long-term monitoring of fish species composition and relative abundance of sharks. -

Identifying Shark Fins: Silky and Threshers Fin Landmarks Used in This Guide

Identifying Shark Fins: Silky and Threshers Fin landmarks used in this guide Apex Trailing edge Leading edge Origin Free rear tip Fin base Shark fins Caudal fin First dorsal fin This image shows the positions of the fin types that are highly prized in trade: the first dorsal, paired Second dorsal fin pectoral fins and the lower lobe of the caudal fin. The lower lobe is the only part of the caudal fin that is valuable in trade (the upper lobe is usually discarded). Second dorsal fins, paired pelvic fins and Lower caudal lobe anal fins, though less valuable, also occur in trade. Pectoral fins The purpose of this guide In 2012, researchers in collaboration with Stony Brook University and The Pew Charitable Trusts developed a comprehensive guide to help wildlife inspectors, customs agents, and fisheries personnel provisionally identify the highly distinctive first dorsal fins of five shark species recently listed in Appendix II of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES): the oceanic whitetip, three species of hammerhead, and the porbeagle. Since then, over 500 officials from dozens of countries have been trained on how to use key morphological characteristics outlined in the guide to quickly distinguish fins from these CITES listed species amongst fins of non-CITES listed species during routine inspections. The ability to quickly and reliably identify fins in their most commonly traded form (frozen and/or dried and unprocessed) to the species level provides governments with a means to successfully implement the CITES listing of these shark species and allow for legal, sustainable trade. -

And Their Functional, Ecological, and Evolutionary Implications

DePaul University Via Sapientiae College of Science and Health Theses and Dissertations College of Science and Health Spring 6-14-2019 Body Forms in Sharks (Chondrichthyes: Elasmobranchii), and Their Functional, Ecological, and Evolutionary Implications Phillip C. Sternes DePaul University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/csh_etd Part of the Biology Commons Recommended Citation Sternes, Phillip C., "Body Forms in Sharks (Chondrichthyes: Elasmobranchii), and Their Functional, Ecological, and Evolutionary Implications" (2019). College of Science and Health Theses and Dissertations. 327. https://via.library.depaul.edu/csh_etd/327 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Science and Health at Via Sapientiae. It has been accepted for inclusion in College of Science and Health Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Via Sapientiae. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Body Forms in Sharks (Chondrichthyes: Elasmobranchii), and Their Functional, Ecological, and Evolutionary Implications A Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science June 2019 By Phillip C. Sternes Department of Biological Sciences College of Science and Health DePaul University Chicago, Illinois Table of Contents Table of Contents.............................................................................................................................ii List of Tables..................................................................................................................................iv -

Species Carcharhinus Brachyurus (Günther, 1870

FAMILY Carcharhinidae Jordan & Evermann, 1896 - requiem sharks [=Triaenodontini, Prionidae, Cynocephali, Galeocerdini, Carcharhininae, Eulamiidae, Loxodontinae, Scoliodontinae, Galeolamnidae, Rhizoprionodontini, Isogomphodontini] GENUS Carcharhinus Blainville, 1816 - requiem sharks [=Aprion, Aprionodon, Bogimba, Carcharias, Eulamia, Galeolamna, Galeolamnoides, Gillisqualus, Gymnorhinus, Hypoprion, Hypoprionodon, Isoplagiodon, Lamnarius, Longmania, Mapolamia, Ogilamia, Platypodon, Pterolamia, Pterolamiops, Uranga, Uranganops] Species Carcharhinus acarenatus Moreno & Hoyos, 1983 - Moroccan shark Species Carcharhinus acronotus (Poey, 1860) - blacknose shark [=remotus] Species Carcharhinus albimarginatus (Rüppell, 1837) silvertip shark [=platyrhynchus] Species Carcharhinus altimus (Springer, 1950) - bignose shark [=radamae] Species Carcharhinus amblyrhynchoides (Whitley, 1934) - graceful shark Species Carcharhinus amblyrhynchos (Bleeker, 1856) - grey reef shark [=coongoola, fowleri, nesiotes, tufiensis] Species Carcharhinus amboinensis (Müller & Henle, 1839) - Java shark [=brachyrhynchos, henlei, obtusus] Species Carcharhinus borneensis (Bleeker, 1858) - Borneo shark Species Carcharhinus brachyurus (Günther, 1870) - copper shark, bronze whaler, narrowtooth shark [=ahenea, improvisus, lamiella, remotoides, rochensis] Species Carcharhinus brevipinna (Müller & Henle, 1839) - great blacktip shark [=brevipinna B, calamaria, caparti, johnsoni, maculipinnis, nasuta] Species Carcharhinus cautus (Whitley, 1945) - nervous shark Species Carcharhinus -

Keeping the Balance.Pdf

Contents Caribbean reef shark (Carcharhinus perezi). Jardines de la Reina, Cuba, March 2008. © OCEANA/ Carlos Suárez IUCN Status: Near Threatened. Executive Summary ..................................................................................................................1 1. Introduction ...........................................................................................................................2 2. Shark status according to the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species .....5 3. United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea ..........................................7 4. International multilateral biodiversity conventions ......................................8 5. European regional environmental conventions .............................................12 6. Shark protection under EU biodiversity regulations ..................................16 7. Conclusions ..........................................................................................................................17 Annex I. Existing multilateral and regional conventions under international environmental law and their provisions for shark protection...................................18 Annex II. Elasmobranch species listed under existing multilateral and regional environmental conventions ...................................................................................19 References ...................................................................................................................................21 Recommendations .................................................................................................................26 -

Preliminary Results from Tag-Recapture Procedures Applied to Lemon Sharks, Negaprion Brevirostris (Poey 1868), at Los Roques Archipelago, Venezuela

Preliminary Results from Tag-Recapture Procedures Applied to Lemon Sharks, Negaprion brevirostris (Poey 1868), at Los Roques Archipelago, Venezuela RAFAEL TAVARES Instituto Nacional de Investigaciones Agrícolas, Isla de Margarita, Estado Nueva Esparta,. Venezuela Centro para la Investigación de Tiburones, Caracas, Distrito Capital, Venezuela ABSTRACT During the period 2005 - 2008, 13 field surveys were conducted within the Archipelago Los Roques in order to examine the population structure and growth of juvenile lemon sharks, Negaprion brevirostris. Tag-recapture procedures were concentrated in the Sebastopol Lagoon (SL), an area previously identified as a nursery ground for this species. During the study, a total of 102 juvenile N. brevirostris (40.4 - 95.0 cm PCL) were captured within the SL; of these, 96 individuals were successfully tagged and released. Length composition was significantly different between sexes (Kruskal-Wallis; p < 0.001). Neonates (mean size: 46.1 cm PCL) were observed during June and July months, indicating that the birth season corresponds to this period. Mean growth rates were 24.2 cm year-1 for males and 21.9 cm/year for females. These estimates indicated that in the study area, juvenile N. brevirostris grow more rapidly than do juveniles in other populations of the same species distributed in the western Atlantic. KEY WORDS: Caribbean Sea, elasmobranchs, growth, nursery areas Resultados Preliminares Obtenidos de la Aplicación del Método de Marcaje y Recaptura en Tiburones Limón, Negaprion brevirostris (Poey 1868), en el Archipiélago Los Roques, Venezuela Durante el periodo 2005 - 2008, se realizaron 13 salidas de campo al Archipiélago Los Roques con el propósito de examinar la estructura de la población y el crecimiento de juveniles de tiburón limón, Negaprion brevirostris. -

A Baited Remote Underwater Video System (BRUVS)

Environ Biol Fish https://doi.org/10.1007/s10641-020-01004-4 A baited remote underwater video system (BRUVS) assessment of elasmobranch diversity and abundance on the eastern Caicos Bank (Turks and Caicos Islands); an environment in transition Stephan Bruns & Aaron C. Henderson Received: 26 January 2020 /Accepted: 5 July 2020 # Springer Nature B.V. 2020 Abstract The present study was undertaken to assess efforts in the Turks and Caicos Islands should continue the diversity and abundance of elasmobranch fishes in to focus on coral reef areas, less dramatic environments coral reef and sand flat environments on the eastern such as sand flats should not be ignored. Caicos Bank, with a view to informing marine spatial planning as the island of South Caicos and its environs Keywords Caribbean region . Chondrichthyes . transition to a tourism-based economy. Using baited Biodiversity . BRUVS . Coral reef remote underwater video systems (BRUVS), the nurse shark Ginglymostoma cirratum, Caribbean reef shark Carcharhinus perezi, spotted eagle ray Aetobatus Introduction narinari, southern stingray Hypanus americanus, lemon shark Negaprion brevirostris, tiger shark Galeocerdo Populations of elasmobranch fishes (sharks, skates, cuvier, blacknose shark Carcharhinus acronotus,and rays) have undergone dramatic declines on a global great hammerhead shark Sphyrna mokarran were ob- scale in recent decades (Dulvy et al. 2014). While in- served to use these waters, with G. cirratum and dustrial longline fleets are responsible for the largest C. perezi being particularly abundant. Species diversity component of elasmobranch landings worldwide and overall abundance was greater in the reef environ- (Worm et al. 2013), landings from artisanal fishers can ment than on the sand flats, but G. -

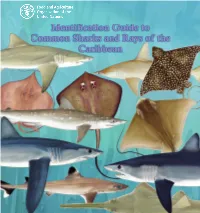

Identification Guide to Common Sharks and Rays of the Caribbean

Identification Guide to Common Sharks and Rays of the Caribbean The designations employed and the presentation of material in this information product do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) concerning the legal or development status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The mention of specific companies or products of manufacturers, whether or not these have been patented, does not imply that these have been endorsed or recommended by FAO in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. The views expressed in this information product are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of FAO. © FAO, 2016 ISBN 978-92-5-109245-3 FAO encourages the use, reproduction and dissemination of material in this information product. Except where otherwise indicated, material may be copied, downloaded and printed for private study, research and teaching purposes, or for use in non-commercial products or services, provided that appropriate acknowledgement of FAO as the source and copyright holder is given and that FAO’s endorsement of users’ views, products or services is not implied in any way. All requests for translation and adaptation rights, and for resale and other commercial use rights should be made via www.fao.org/contact-us/licence-request or addressed to [email protected]. FAO information products are available on the FAO website (www.fao.org/publications) and can be purchased through [email protected]. -

Deep-Diving and Diel Changes in Vertical Habitat Use by Caribbean Reef Sharks Carcharhinus Perezi

Vol. 344: 271–275, 2007 MARINE ECOLOGY PROGRESS SERIES Published August 23 doi: 10.3354/meps06941 Mar Ecol Prog Ser Deep-diving and diel changes in vertical habitat use by Caribbean reef sharks Carcharhinus perezi Demian D. Chapman1, 2,*, Ellen K. Pikitch3, Elizabeth A. Babcock2, Mahmood S. Shivji1 1Guy Harvey Research Institute/Nova Southeastern University Oceanographic Center, 8000 N. Ocean Drive, Dania Beach, Florida 33004, USA 2Pew Institute for Ocean Science, Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science, University of Miami, 4600 Rickenbacker Causeway, Miami, Florida 33133, USA 3Pew Institute for Ocean Science, Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science, University of Miami, 126 E. 56th Street, New York, New York 10022, USA ABSTRACT: Longline sampling (83 sets) supplemented with 6 pop-off archival transmitting (PAT) tag deployments were used to characterize vertical habitat use by Caribbean reef sharks Carcharhinus perezi at Glover’s Reef atoll, Belize. Longline catch-per-unit-effort (CPUE) in 2 shallow reef habitats (lagoon <18 m depth, fore-reef <40 m depth) underwent significant nocturnal increases for sharks larger than 110 cm total length (TL), but not for smaller sharks. Nocturnal CPUE of small sharks appeared to increase in the lagoon and decrease on the fore-reef, suggestive of movements to avoid larger conspecifics. PAT tag deployments (7 to 20 d) indicate that large C. perezi generally increased the amount of time they spent in the upper 40 m of the water column during the night, and inhabited much greater depths and tolerated lower temperatures than previously described. The wide vertical (0 to 356 m) and temperature range (31 to 12.4°C) documented for this top-predator reveals ecologi- cal coupling of deep and shallow reef habitats and has implications for Marine Protected Area (MPA) design. -

Shark Fishing in Florida January 13, 2015 Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission Division of Marine Fisheries Management Importance of Sharks

Photo credit: Heidi Thoricht Shark Fishing in Florida January 13, 2015 Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission Division of Marine Fisheries Management Importance of Sharks . Vital role in marine ecosystems . Apex predators . Keystone species . Economic value . Recreation . Commercial/food . Florida’s coastal waters are Essential Fish Habitat (EFH) . Pregnant females enter state waters to pup at known times of year . Critical nursery habitat is often found in shallow state waters Reef Shark Photo credit: Heidi Thoricht Who Manages Sharks? Each Atlantic coastal state manages sharks from shore to 3 miles Florida manages sharks from Manages interstate fisheries shore to 9 from shore to 3 miles on miles in Atlantic Coast Gulf Office of Sustainable Fisheries Division of Highly Migratory Species (HMS) Manages tunas, swordfish, billfish, and sharks in federal waters Shark Fishing from Shore . Allowed in Florida with a recreational saltwater fishing license . Public perception that fishing from shore alters shark behavior in nearshore waters . Fear among the public that fishing from shore could increase the likelihood of shark attacks . Land based anglers chum from shore and fishing piers when targeting other species, including baitfish and snappers . Shark anglers report they rarely chum, as it is ineffective due to current and wave action . 2011 received request from county government to look at shore based regulations . No evidence showing an increase in shark attacks associated with fishing from shore . Ultimately, Commission did not take action Shark Fishing in Florida . Economically important in Florida . Exciting sport, drawing participants worldwide . Opportunities for shark fishing that can’t be found elsewhere . Commission values access to our shared resources for all user groups .