Law: the Wind Beneath My Wings

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Endless Summer Song List

ENDLESS SUMMER BAND MASTER SONG LIST 30's-40's continued… continued… B FLAT BLUES BEGIN THE BEGUINE GET READY SIXTEEN CANDLES BUGLE BOY GIVE ME SOME LOVING SOUL & INSPIRATION CAB DRIVER GREAT BALLS O FIRE SOUL MEDLEY CHATANOOGA CHO CHO GREEN RIVER SOULMAN DANNY BOY HAND JIVE STAND BY ME FLY ME TO THE MOON HANG ON SLOOPY STOP IN THE NAME OF LOVE GIRL FROM IPANEMA HANKY PANKY SUMMER TIME BLUES HELLO DOLLY HARD DAYS NIGHT SURFIN USA HIT THE ROAD JACK HEAR U KNOCKIN SWEET SOUL MUSIC IN THE MOOD HOLD ON IM COMING TEDDY BEAR MACK THE KNIFE HOUNDOG TEQUILA MISTY I FALL TO PIECES THE LETTER MONA LISA I FEEL GOOD THE STROLL MOONLIGHT SERENADE I FOUGHT THE LAW THE WANDERER MR SANDMAN I GET AROUND THE WAY YOU LOOK TONIGHT ON BROADWAY I HEARD IT THROUGH THE GRAPEVINE THINK SATIN DOLL I SAW HER STANDING THERE TICKET TO RIDE SAVE THE LAST DANCE FOR ME ITS MY PARTY TRAVELING BAND SENTIMENTAL JOURNEY ITS ALL RIGHT TUTTI FRUTTI SHADOW OF YOUR SMILE JAILHOUSE ROCK TWIST STRING OF PEARLS JENNY TAKE A RIDE UNCHAINED MELODY TAKE THE A - TRAIN JIM DANDY VIVA LAS VEGAS THAT SUNDAY THAT SUMMER JOHNNY B GOOD WAKE UP LIL SUSIE THAT’S LIFE KANSAS CITY WHAT A WONDERFUL WORLD UNFORGETTABLE KNOCK ON WOOD WHEN A MAN LOVES A WOMAN WHY HAVENT I LA BAMBA WHOLE LOTTA SHAKING GOIN' ON 50's-60's LAND OF 1000 DANCES WILD THING All SHOOK UP LETS TWIST AGAIN WOOLY BULLY ARE YOU LONESOME TONIGHT LION SLEEPS TONIGHT AT THE HOP LOCOMOTION BABY LOVE LOUIE LOUIE BARBARA ANN LOVIN FEELIN BLACK IS BLACK LUCILLE BORN TO BE WILD MIDNIGHT HOUR BOYFRIENDS BACK MONY MONY BROWN EYED GIRL -

Jazz Quartess Songlist Pop, Motown & Blues

JAZZ QUARTESS SONGLIST POP, MOTOWN & BLUES One Hundred Years A Thousand Years Overjoyed Ain't No Mountain High Enough Runaround Ain’t That Peculiar Same Old Song Ain’t Too Proud To Beg Sexual Healing B.B. King Medley Signed, Sealed, Delivered Boogie On Reggae Woman Soul Man Build Me Up Buttercup Stop In The Name Of Love Chasing Cars Stormy Monday Clocks Summer In The City Could It Be I’m Fallin’ In Love? Superstition Cruisin’ Sweet Home Chicago Dancing In The Streets Tears Of A Clown Everlasting Love (This Will Be) Time After Time Get Ready Saturday in the Park Gimme One Reason Signed, Sealed, Delivered Green Onions The Scientist Groovin' Up On The Roof Heard It Through The Grapevine Under The Boardwalk Hey, Bartender The Way You Do The Things You Do Hold On, I'm Coming Viva La Vida How Sweet It Is Waste Hungry Like the Wolf What's Going On? Count on Me When Love Comes To Town Dancing in the Moonlight Workin’ My Way Back To You Every Breath You Take You’re All I Need . Every Little Thing She Does Is Magic You’ve Got a Friend Everything Fire and Rain CONTEMPORARY BALLADS Get Lucky A Simple Song Hey, Soul Sister After All How Sweet It Is All I Do Human Nature All My Life I Believe All In Love Is Fair I Can’t Help It All The Man I Need I Can't Help Myself Always & Forever I Feel Good Amazed I Was Made To Love Her And I Love Her I Saw Her Standing There Baby, Come To Me I Wish Back To One If I Ain’t Got You Beautiful In My Eyes If You Really Love Me Beauty And The Beast I’ll Be Around Because You Love Me I’ll Take You There Betcha By Golly -

Song Suggestions for Special Dances

SONG SUGGESTIONS FOR SPECIAL DANCES PARTY EXCITEMENT www.partyexcitement.com Top 50 Bride & Groom First Dance Songs (Everything I Do) I do it for you by Bryan Adams A Thousand Years by Christina Perri All My Life by K‐Ci & JoJo Amazed by Lonestar At Last by Etta James Better Together by Jack Johnson Bless the Broken Road by Rascal Flatts By Your Side by Sade Can’t Help Falling in Love by Elvis Presley Chasing Cars by Snow Patrol Come Away with Me by Norah Jones Cowboys and Angels by Dustin Lynch Crazy Girl by Eli Young Band Crazy Love by Van Morrison Everything by Michael Buble Faithfully by Journey First Day of My Life by Bright Eyes God Gave Me You by Blake Shelton Hold on by Michael Buble I Cross my Heart by George Strait I Don’t Want to Miss a Thing by Aerosmith I Gotta Feeling by Black Eyed Peas I won’t give up by Jason Mraz I’ll be by Edwin McCain Into the Mystic by Van Morrison It’s Your Love by Tim McGraw and Faith Hill Let’s Stay Together by Al Green Lucky by Jason Mraz & Colbie Caillat Make You Feel My Love by Adele Making Memories of Us by Keith Urban Marry Me by Train Me and You by Kenny Chesney My Best Friend by Tim McGraw She’s everything by Brad Paisley Smile by Uncle Kracker Stand By Me by Ben E. King The Way you look tonight by Frank Sinatra Then by Brad Paisley This Year’s Love by David Gray Unchained Melody by Righteous Brothers Wanted by Hunter Hayes What a Wonderful World by Louis Armstrong When You Say Nothing at All by Alison Krauss Wonderful Tonight by Eric Clapton You and Me by Dave Matthews Band You are the Best -

Grand Entrances Speciality Dances

Bat Mitzah Grand Entrances 1. Isn’t She Lovely – Stevie Wonder 14. Perfect Day ‐ Hoku 2. I’m Every Women – Whiteny Houston 15. I’m A Star ‐ Prince 3. Everything She Does Is Magic – Police 16. Pretty Women – Roy Orbison 4. Just Dance – Lady GaGa & Colby O’Donis 17. Waiting for Tonight – Jennifer Lopez 5. Glamorous – Fergie 18. Brown Eyed Girl – Van Morrison 6. Single Ladies – Beyonce 19. What Dreams Are Made Of – Hillary Duff 7. I’m Coming Out – Diana Ross 20. Get the Party Started ‐ Pink 8. Dancing Queen – Abba 21. Let’s Get It Started – Black Eyed Peas 9. She’s A Lady – Tom Jones 22. That Lady – Isley Brothers 10. Simply Irresistible – Robert Palmer 23. Don’t Ya – Pussycat Dolls 11. Beautiful Day – U2 24. Material Girl – Madonna 12. Forever – Chris Brown 25. One – Chrous Line 13. Beautiful – Akon 26. Beautiful – Snoop Dogg & Pharell Bar Mitzvah Grand Entrances 1. Macho Man – Village People 12. Yeah ‐ Usher 2. Wild Thing – Troggs/ Ton Loc 13. All Star ‐ Smashmouth 3. Let’s Hear It For the Boys – Denise Williams 14. Sharp Dressed Man – ZZ Tops 4. Pretty Fly (for a White Guy) – The Offspring 15. Party Like a Rock Star – Shop Boyz 5. #1 – Nelly 16. Fly Eagles Fly – Theme Song 6. We Fly High – Jim Jones 17. Chicago Bulls Theme – Theme Song 7. I’m Too Sexy – Right Said Fred 18. Born to Be Wild – Steppinwolf 8. Let’s Get It Started – Black Eyed Peas 19. World’s Greatest – R. Kelly 9. Mr. Big Stuff – Jean Knight 20. -

Montage Song Suggestions

MONTAGE SONG LIST INTRODUCTION MONTAGE SONGS Song Artist Angels Lullaby Richard Marx A Kiss To Build A Dream On Louis Armstrong As Time Goes By Jimmy Durante Beautiful In My Eyes Joshua Kadison Beautiful Baby Bing Crosby Beautiful Boy Elton John Because You Loved Me Celine Dion Billionaire Travis McCoy Boys Keep Swinging David Bowie Brighter Than The Sun Colbie Caillat Brown Eyed Girl Van Morrison Bubbly Colbie Butterfly Fly Away Miley Cyrus Can You Feel The Love Tonight Elton John Circle Of Life Elton John Count on Me Bruno Mars Everything I Do, I Do It For You Brian Adams Fireflies Owl City First Time I Ever Saw Your Face Celine Dion First Time I Ever Saw Your Face Roberta Flack Flying Without Wings Ruben Studdard God Must Have Spent A Little More Time NSYNC Grenade Bruno Mars Hero Mariah Carey Hey, Soul Sister Train I Am Your Child Barry Manilow I Don’t Wanna Miss A Thing Aerosmith I Hope You Dance Lee Ann Womack I Learned From You Miley Cyrus In Your Eyes Peter Gabriel If I Could Ray Charles Just The Way You Are Bruno Mars Lean on Me Glee Let Them Be Little Lonestar Mad World Adam Lambert No Boundaries Kris Allen Ordinary Miracles Amy Sky She’s The One Rubbie Williams Smile Glee The Only Exception Paramore Through The Years Kenny Rogers Times Of Your Life Paul Anka Tiny Dancer Elton John Smile Uncle Kracker U Smile Justin Beiber What A Wonderful World Louis Armstrong What A Wonderful World Israel Kamakawiwo'ole Wind Beneath My Wings Bette Midler You Are So Beautiful Joe Cocker MIDDLE MONTAGE SONGS Song Artist Ain’t No Mountain High Enough Diana Ross Allstar Smashmouth Are You Gonna Be My Girl Jet American Girl Tom Petty Angel Lionel Richie Animal Neon Trees Beat Of My Heart Hilary Duf Beautiful Day U2 Beautiful Girl Sean Kingston Billionaire Travis McCoy Born To Be Wild Steppenwolf Bottle It Up Sara Bareilles Break Out Miley Cyrus California Gurls Katy Perry Cooler Than Me Mike Posner Daddys Girl Miley Cyrus Dominoe Jessie J. -

90'S-2000'S Ballads 1. with Open Arms

90’s-2000’s Ballads 14. Fooled Around And Fell In Love - Elvin Bishop 1. With Open Arms - Creed 15. I Just Wanna Stop - Gino Vannelli 2. Truly Madly Deeply - Savage Garden 16. We've Only Just Begun - The Carpenters 3. I Knew I Loved You - Savage Garden 17. Easy - Commodores 4. As Long As You Love Me - Backstreet Boys 18. Three Times A Lady - Commodores 5. Last Kiss - Pearl Jam 19. Best Of My Love - Eagles 6. Aerosmith - Don't Wanna Miss A Thing 20. Lyin' Eyes - Eagles 7. God Must Have Spent A Little More Time - N'Sync 21. Oh Girl - The Chi-Lites 8. Everything I Do - Bryan Adams 22. That's The Way Of The World - Earth Wind & Fire 9. Have I Told You Lately - Rod Stewart 23. The Wedding Song - Paul Stokey 10. When A Man Loves A Woman - Michael Bolton 24. Wonder Of You - Elvis Presley 11. Oh Girl - Paul Young 25. You Are The Sunshine Of My Life - Stevie Wonder 12. Love Will Keep Us Alive - Eagles 26. You've Got A Friend - James Taylor 13. Can You Feel The Love Tonight - Elton John 27. Annie's Song - John Denver 14. I Can't Fight This Feeling Anymore - R.E.O. 28. Free Bird - Lynyrd Skynyrd 15. Unforgettable - Natalie Cole 29. Riders On The Storm - Doors 16. Endless Love - Luther Vandross 30. Make It With You - Bread 17. Forever In Love - Kenny G 31. If - Bread 18. Butterfly Kisses - Bob Carlisle 32. Fallin' In Love - Hamilton, Joe Frank & Reynolds 19. Unforgettable - Nat King & Natalie Cole 33. -

BALLADS JAZZ/BIG BAND FUNK/MOTOWN, 70'S/80'S ROCK TOP 40 DANCE: 90'S - CURRENT

BALLADS JAZZ/BIG BAND FUNK/MOTOWN, 70's/80's ROCK TOP 40 DANCE: 90's - CURRENT A ThousAnd YEArs- ChrisHnA Perri At Last- Etta James Ain't No MountAin High Enough- Marvin GAyE & TAmmi TErrEAll Right Now- Rod StEwArt 24k Magic- Bruno Mars All of Me- John Legend A Wink & A Smile- Harry Connick, JR. Ain't Too Proud To BEg- ThE TemptAHons AmEricAn Girl- Tom PeYy ApAchE- SugAr Hill Gang AmAZEd- Lonestar Blue Bossa- Kenny Dorham All Night Long- LionEl RichiE All SummEr Long- Kid Rock Bad Guy- Billie Eilish Because You LovEd Me- CElinE Dion Come Away With Me- Nora Jones Bad Girls- Donna SummEr Brown EyEd Girl- Van Morrison BlurrEd Lines- Robin Thicke & Pharrell Bless the BrokEn RoAd- RascAl FlAYs Don't Know Why- Nora Jones BEst Of My LovE- ThE EmoHons Don't Stop BeliEving- JournEy Boom Boom Pow- BlAck EyEd PEAs Can't Help Falling In LovE- Elvis PrEslEy Dream A Little Dream of Me- Ella FitzgeraldBoogiE OogiE OogiE- A TAstE of HonEy HArd to HAndlE- BlAck Crowes Bust A MovE- Young MC Could Not Ask For MorE- Edwin McCAin Everything- Michael Buble Brick HousE- ThE CommodorEs Lights- Journey Cake By The Ocean- DNCE CrAZy- PAtsy ClinE Fly Me to the Moon- Frank Sinatra Build Me Up BuYErcup- ThE FoundAHons Livin' On A PrAyEr- Bon Jovi CaliforniA Girls- Katy PErry CrAZy Love- VAn Morrison In the Mood- Glenn Miller BusHn' LoosE- Chuck Brown Lose Your LovE- Ou^ield CAll Me MaybE- CArly RaE JEpsEn ForEvEr Young- Rod StEwArt It Had to be You- Harry Connick, JR. -

Song List for Your Review

west coast music Everyday People Please find attached the ‘Everyday People’ song list for your review. SPECIAL DANCES: Please note that we will need to have your special dance requests, (i.e. First Dance, Father/Daughter Dance, etc) FOUR WEEKS prior to your event so that we can confirm that the band will be able to perform the song(s) and so that we have time to locate sheet music and audio. In cases where sheet music is not available or an arrangement for the full band is needed, this gives us time to properly prepare the music. Clients are not obligated to send in a list of general song requests. Many of our clients ask that the band just react to whatever their guests are responding to on the dance floor. Our clients that do provide us with song requests do so in varying degrees. Most clients give us a handful of songs they want played and avoided. If you desire the highest degree of control (allowing the band to only play within the margin of songs requested), we would ask for a minimum 80 requests. ‘LOW ROTATION REQUESTS: We will also need any General Requests that are chosen from the ‘Low Rotation’ portion of this song list (pages 8-9) FOUR WEEKS in advance prior to your event. The songs from the ‘Low Rotation’ section are not in the active Everyday People song rotation, so the band would need the extra time to prepare them MODERN/TOP 40 24k Magic – Bruno Mars Call Me Maybe – Carly Rae Jepsen A Thousand Years – Christina Perri Call You Girlfriend - Robyn Adorn – Miguel Can’t Feel My Face – The Weeknd Ascension – Maxwell Can’t Hold -

Rehab Amy Winehouse

Envee Repertoire List UPDATED: 2 -23-2018 Jazz/Easy Listening Al Green - Let's Stay Together Amy Winehouse- Back to Black Amy Winehouse - Rehab Amy Winehouse - Tears Dry On Their Own Amy Winehouse - The Girl From Ipanema Amy Winehouse - Valerie Amy Winehouse - Wake Up Alone Andy Williams - Moon River Anita Baker - Giving You The Best That I've Got Annie Lenox - I Put a Spell On You Aretha Franklin - Natural Woman B.B.King - Stand By Me Bill Withers - Ain't No Sunshine Bonnie Raiit - I Can't Make You Love Me Carole King - Will You Still Love Me Tomorrow Cole Porter - Every Time We, Say Goodbye Connie Francis - Where The Boys Are Corinne Bailey Ray - Put Your Records On Dinah Washington - Is You Is, Or Is You Ain't My Baby Ella Fitzgerald - Cheek to Cheek Ella Fitzgerald - Dream a Little Dream Ella Fitzgerald - Someone To Watch Over Me Ella Fitzgerald - Summertime Ella Fitzgerald - What a Difference a Day Makes Eva Cassidy - Somewhere Over The Rainbow Elvis Presley - I Can't Help Falling In Love With You Etta James - At Last Etta James - I Heard (church bells ringing) Frank Sinatra - Fly Me To The Moon Frank Sinatra - It Had To Be You Frank Sinatra - I've Got You Under My Skin Frankie Valli - Can't Take My Eyes Off You Gladys Knight - Since I Fell For You Johnny Mathis –Misty Johnny Mathis - My Funny Valentine Lana Del Ray - Young And Beautiful (PMJ version) Lena Horne - Stormy Weather Leonard Cohen - Dance Me to The End Of Love Linda Ronstadt - Blue Bayou Louis Armstrong - It Don't Mean A Thing Louis Armstrong - What a Wonderful World Magic! - Rude (PMJ Version) Madonna - Sooner or Later Maroon 5 - Sunday Morning Envee Repertoire List UPDATED: 2 -23-2018 Marvin Gaye - What's Going On Megan Trainor - All About That Bass (PMJ Version) Michael Bublè – Sway Michael Bublè - That's All Nat King Cole - Autumn Leaves Nat King Cole - Sentimental Reasons Nat King Cole - The Very Thought of You Nat King Cole - Unforgettable Nat King Cole - When I Fall In Love Natalie Cole - Almost Like Being In Love Natalie Cole - Don't Get Around Much Anymore Natalie Cole - L.O.V.E. -

Most Requested Parents Dance Songs and Cake Cutting Song Suggestions

Most Requested Parents Dance Songs and Cake Cutting Song Suggestions Bride and Father Groom and Mother I Loved Her First (Heartland) A Song For My Son (Mikki Viereck) My Special Angel (Bobby Helms) The First Lady In My Life (Paul Todd) Butterfly Kisses (Bob Carlisle) Because You Loved Me (Celine Dion) I’ll Always Be Your Daughter (Lynn Leonti) You Raise Me Up (Josh Groban) It Won’t Be Like This For Long (Darius Rucker) Have I Told You Lately (Rod Stewart) Daddy’s Little Girl (Al Martino/Mill Brothers/Michael Bolton)) Sunrise, Sunset (Fiddler on the Roof- Jewish wedding) Father’s Eyes (Amy Grant) Through The Years (Kenny Roger) Daddy’s Little Girl Is A Big Girl Now (Paul Anka) Angels (Randy Travis) And I Love Her (The Beatles) Turn Around (Various Artists) Through The Years (Kenny Rogers) Unforgettable (Nat King/Natalie Cole) Cinderella (Steven Curtis Chapman) I Hope you Dance (LeAnn Womack) Turn Around (Various Artists) Song For Mamma (Boys II Men) Unforgettable (Nat King/Natalie Cole) It’s Your Song (Garth Brooks) Wind Beneath My Wings (Bette Midler) The Woman In My Life (Phil Vassar) Daddy’s Hands (Holly Dunn) Wind Beneath My Wings (Bette Midler) My Girl (Temptations) What a Wonderful World (Louis Armstrong) A Song For My Daughter (Ray Allaire) You Are My Child (Barry Manilow) Daddy’s Little Girl (Kippi Brannon) The Man You’ve Become (Molly Pasutti) The Way You Look Tonight (Frank Sinatra, Michael Buble) Simple Man (Lynyrd Skynyrd/Shinedown) Lullabye (Billy Joel) I’ll Always Be Your Mother (Lynn Leonti/Jim McShane) My Wish (Rascal Flatts) You Are The Sunshine Of My Life (Stevie Wonder) Special Person My Little Girl (Tim McGraw) (Steve Kirwan) A Whole New World (Regina Belle/Peabo Bryson) Because You Loved Me (Celine Dion) In My Daughter’s Eyes (Martina McBride) There You’ll Be (Faith Hill) Unforgettable (Nat King/ Natalie Cole) Dance With My Father (Luther Vandross) Stand By Me (Ben E. -

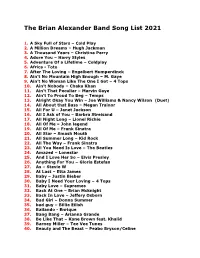

The Brian Alexander Band Song List 2021

The Brian Alexander Band Song List 2021 1. A Sky Full of Stars – Cold Play 2. A Million Dreams – Hugh Jackman 3. A Thousand Years – Christina Perry 4. Adore You – Harry Styles 5. Adventure Of a Lifetime – Coldplay 6. Africa - Toto 7. After The Loving – Engelbert Humperdinck 8. Ain’t No Mountain High Enough – M. Gaye 9. Ain’t No Woman Like The One I Got – 4 Tops 10. Ain’t Nobody – Chaka Khan 11. Ain’t That Peculiar – Marvin Gaye 12. Ain’t To Proud To Beg – Temps 13. Alright Okay You Win – Joe Williams & Nancy Wilson (Duet) 14. All About that Bass – Megan Trainor 15. All For U – Janet Jackson 16. All I Ask of You – Barbra Streisand 17. All Night Long – Lionel Richie 18. All Of Me – John legend 19. All Of Me – Frank Sinatra 20. All Star – Smash Mouth 21. All Summer Long – Kid Rock 22. All The Way – Frank Sinatra 23. All You Need Is Love – The Beatles 24. Amazed – Lonestar 25. And I Love Her So – Elvis Presley 26. Anything For You – Gloria Estefan 27. As – Stevie W 28. At Last – Etta James 29. Baby – Justin Bieber 30. Baby I Need Your Loving – 4 Tops 31. Baby Love – Supremes 32. Back At One – Brian Mcknight 33. Back In Love – Jeffery Osborn 34. Bad Girl – Donna Summer 35. bad guy – Billie Eilish 36. Bailando - Enrique 37. Bang Bang – Arianna Grande 38. Be Like That – Kane Brown feat. Khalid 39. Barney Miller – Tee Vee Tunes 40. Beauty and The Beast – Peabo Bryson/Celine 41. Because You Loved Me – Celine Dion 42. -

Download Song List

ETA Songlist 70's/80's/90's O.P.P. Naughty by Nature A Little Respect Wheatus Oh What a Night 4 Seasons Africa Toto Only The Good Die Young Billy Joel Ain't No Stopping Us Now McFadden/Whitehead Play That Funky Music Wild Cherry Ain't Nobody Chaka Khan PYT Michael Jackson All Night Long Lionel Richie (Ride With Me) Must Be the Nelly Money Baby I Love Your Way Peter Frampton September Earth Wind and Fire Best of My Love Emotions Shake Your Body Michael Jackson Billy Jean Michael Jackson Shakedown Street Greatful Dead Boogie Oogie Oogie Taste of Honey Super Freak Rick James Brickhouse Commodores Sweet Caroline Neil Diamond Can't Get Enough of Your Love Barry White That's the Way I Like It K.C. and the Sunshine Band Come On Eileen Dexy's Midnight Runners This Is How We Do It Montell Jordan Copacabana Barry Manillow This Will Be (An Everlasting Natalie Cole Love) Crazy Gnarles Barkley To Be Real Cheryl Lynn Crazy In Love Beyonce Turn the Beat Around Vickie Sue Robinson Crazy Little Thing Called Love Queen Wannabe Spice Girls Dance to the Music Sly and the Family Stone We Are Family Sister Sledge Dancing Queen Abba You Can Call Me Al Paul Simon Don't Leave Me This Way Thelma Houston Ballads Don't Stop Believing Journey Always and Forever Heatwave Don't Stop till You Get Enough Michael Jackson Because You Love Me Celine Dion Everyday People Arrested Development Better Together Jack Johnson Faith George Michael Can't Take My Eyes Off of You 4 Seasons/Lauren Hill Freedom George Michael Crazy Love Van Morrison Get Down on It Kool and the Gang Daughters John Mayer Get Down Tonight K.C.