Legislative Assembly

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Budget Estimates 2005-06 (Supplementary)

E565_06 attachment MP name Electorate Letter dated ACT Ms Annette Ellis MP Canberra 22-Aug-05 Mr Bob McMullan MP Fraser 22-Aug-05 NT Mr David Tollner MP Solomon 12-Sep-05 QLD Mr Bernie Ripoll MP Oxley 19-Sep-05 The Hon Robert Katter MP Kennedy 19-Sep-05 Mr Wayne Swan MP Lilley 19-Sep-05 Dr Craig Emerson MP Rankin 19-Sep-05 Mr Kevin Rudd MP Griffith 19-Sep-05 The Hon Arch Bevis MP Brisbane 19-Sep-05 Ms Kirsten Livermore MP Capricornia 19-Sep-05 The Hon David Jull MP Fadden 19-Sep-05 Mr Andrew Laming MP Bowman 19-Sep-05 The Hon De-Anne Kelly MP Dawson 19-Sep-05 Mr Ross Vasta MP Bonner 19-Sep-05 The Hon Mal Brough MP Longman 19-Sep-05 The Hon Warren Truss MP Wide Bay 19-Sep-05 Mr Cameron Thompson MP Blair 19-Sep-05 Mr Steven Ciobo MP Moncrieff 19-Sep-05 The Hon Teresa Gambaro MP Petrie 19-Sep-05 The Hon Peter Dutton MP Dickson 19-Sep-05 Mr Michael Johnson MP Ryan 19-Sep-05 The Hon Gary Hardgrave MP Moreton 19-Sep-05 The Hon Warren Entsch MP Leichhardt 19-Sep-05 Mrs Margaret May MP McPherson 19-Sep-05 Mr Peter Lindsay MP Herbert 19-Sep-05 The Hon Bruce Scott MP Maranoa 19-Sep-05 The Hon Peter Slipper MP Fisher 19-Sep-05 The Hon Alex Somlyay MP Fairfax 19-Sep-05 Mr Paul Neville MP Hinkler 19-Sep-05 The Hon Ian Macfarlane MP Groom 19-Sep-05 Mrs Kay Elson MP Forde 19-Sep-05 SA Dr Andrew Southcott MP Boothby 19-Sep-05 Ms Kate Ellis MP Adelaide 19-Sep-05 Mr Steve Georganas MP Hindmarsh 19-Sep-05 Mr Rodney Sawford MP Port Adelaide 19-Sep-05 Mr Patrick Secker MP Barker 19-Sep-05 Mr Barry Wakelin MP Grey 19-Sep-05 Mr Kym Richardson MP Kingston 19-Sep-05 -

Australia's Honeybee News

AUSTRALIA’S HONEYBEE NEWS “The Voice of the Beekeeper” Volume 8 Number 4 July - August 2015 www.nswaa.com.au DENMAR APIARIES ITALIAN Prices effective from 1 July 2012 UNTESTED 1-10 .......... $24.55 each 11-49 ........ $18.50 each 50+ ........... $16.00 each ISOLATED MATED BREEDERS $280.00 EACH TERMS 7 DAYS Late Payments - Add $2 Per Queen PAYMENT BY: Cheque or Direct Debit Details on ordering QUEEN BEES PO Box 99 WONDAI Queensland 4606 Phone: (07) 4168 6005 Fax: (07) 4169 0966 International Ph: +61 7 4168 6005 Fax: +61 7 4169 0966 Email: [email protected] Specialising in Caucasian Queen Bees 1 – 9 .…. $26 ea 10 – 49 .…. $22 ea 50 – 199 ..… $19.50 ea 200 and over per season ….. Discounts apply Queen Cells ….. $6 ea – collect only Post and Handling $15 per dispatch under 50 qty. Prices include GST John or Stephen Covey Valid September 2015 to March 2016 Email: [email protected] Breeder Queens - $550 Ph: 0427 046 966 Naturally mated on a remote island PO Box 72 Jimboomba QLD 4280 Terms: Payment 10 days prior to dispatch HONEY Honey & Beeswax for sale? Call us for a quote Phone 07 3271 2830 Fax 07 3376 0017 Mobile 0418 786 158 LLoyd & Dawn Smith 136 Mica Street, Carole Park Qld 4300 Committed to maximising returns to beekeepers Email: [email protected] Complete Line of Beekeeping Equipment and Supplies P: 02 6226 8866 M: 0408 260 164 10 Vine Close, Murrumbateman NSW 2582 E: [email protected] W: www.bindaree.com.au AUSTRALIA’S HONEYBEE NEWS The official Journal of the NSW Apiarists’ Association (NSWAA) www.nswaa.com.au Published -

Irsgeneraldistributionpaper July 03

INFORMATION, ANALYSIS AND ADVICE FOR THE PARLIAMENT INFORMATION AND RESEARCH SERVICES Chronology No. 3 2003–04 Telstra Sale: Background and Chronology This chronology outlines the history of the Telstra privatisation process. It documents some of the key dates and policy processes associated with the first and second tranche sales of Telstra. It also outlines some of the key inquiries and legislative conditions required for each stage of the sale. Grahame O'Leary Economics, Commerce and Industrial Relations Group 15 September 2003 DEPARTMENT OF THE PARLIAMENTARY LIBRARY ISSN 1442-1992 Copyright Commonwealth of Australia 2003 Except to the extent of the uses permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means including information storage and retrieval systems, without the prior written consent of the Department of the Parliamentary Library, other than by Senators and Members of the Australian Parliament in the course of their official duties. This paper has been prepared for general distribution to Senators and Members of the Australian Parliament. While great care is taken to ensure that the paper is accurate and balanced, the paper is written using information publicly available at the time of production. The views expressed are those of the author and should not be attributed to the Information and Research Services (IRS). Advice on legislation or legal policy issues contained in this paper is provided for use in parliamentary debate and for related parliamentary purposes. This paper is not professional legal opinion. Readers are reminded that the paper is not an official parliamentary or Australian Government document. -

Why the Telstra Agreement Will Haunt the National Party Lessons from the Democrats’ GST Deal

THE AUSTRALIA INSTITUTE Why the Telstra agreement will haunt the National Party Lessons from the Democrats’ GST Deal Andrew Macintosh Debra Wilkinson Discussion Paper Number 82 September 2005 ISSN 1322-5421 ii © The Australia Institute. This work is copyright. It may be reproduced in whole or in part for study or training purposes only with the written permission of the Australia Institute. Such use must not be for the purposes of sale or comme rcial exploitation. Subject to the Copyright Act 1968, reproduction, storage in a retrieval system or transmission in any form by any means of any part of the work other than for the purposes above is not permitted without written permission. Requests and inquiries should be directed to the Australia Institute. The Australia Institute iii Table of Contents Tables and Figures v Acknowledgements vi Summary vii 1. Introduction 1 2. The Telstra agreement 3 2.1 Regulatory commitments 3 2.2 Spending commitments 4 3. The flaws in the spending component of the Telstra agreement 7 3.1 Policy flaws 7 3.2 Political flaws 10 4. The GST/MBE deal 12 4.1 Background on the GST/MBE deal 12 4.2 The outcomes of the GST/MBE deal 14 5. The GST/MBE deal and the Telstra agreement 23 5.1 Comparing the deals 23 5.2 Lessons for the Nationals 27 6. Conclusions 29 References 31 Telstra and the GST iv The Australia Institute v Tables and Figures Table 1 Funding commitments made by the Howard Government 12 concerning MBE expenditure initiatives ($million) Table 2 Estimated actual spending on the MBE expenditure programs over 14 their four-year life span (2000/01-2003/04) ($million) Table 3 Spending on the MBE expenditure programs projected in 2005/06 15 federal budget (2004/05-2008/09) ($million) Table 4 Nationals’ Telstra agreement vs. -

Thesis August

Chapter 1 Introduction Section 1.1: ‘A fit place for women’? Section 1.2: Problems of sex, gender and parliament Section 1.3: Gender and the Parliament, 1995-1999 Section 1.4: Expectations on female MPs Section 1.5: Outline of the thesis Section 1.1: ‘A fit place for women’? The Sydney Morning Herald of 27 August 1925 reported the first speech given by a female Member of Parliament (hereafter MP) in New South Wales. In the Legislative Assembly on the previous day, Millicent Preston-Stanley, Nationalist Party Member for the Eastern Suburbs, created history. According to the Herald: ‘Miss Stanley proceeded to illumine the House with a few little shafts of humour. “For many years”, she said, “I have in this House looked down upon honourable members from above. And I have wondered how so many old women have managed to get here - not only to get here, but to stay here”. The Herald continued: ‘The House figuratively rocked with laughter. Miss Stanley hastened to explain herself. “I am referring”, she said amidst further laughter, “not to the physical age of the old gentlemen in question, but to their mental age, and to that obvious vacuity of mind which characterises the old gentlemen to whom I have referred”. Members obviously could not afford to manifest any deep sense of injury because of a woman’s banter. They laughed instead’. Preston-Stanley’s speech marks an important point in gender politics. It introduced female participation in the Twenty-seventh Parliament. It stands chronologically midway between the introduction of responsible government in the 1850s and the Fifty-first Parliament elected in March 1995. -

Acon Anti-Violence Project

ACON ANTI-VIOLENCE PROJECT ............................................................................................ 22695 ALBURY AVIATION HISTORY .................................................................................................. 22713 ANGLICARE STREET OUTREACH TEAM ................................................................................ 22702 ARCTIC STAR MEDAL RECIPIENT PETER RUDD ................................................................... 22696 AUSTRALIAN INTERNATIONAL FUTSAL TEAM MEMBER JASON LITTLE........................ 22699 BALLROOM DANCER DES HARPER......................................................................................... 22696 BLACKTOWN HOSPITAL MATERNITY WARD ....................................................................... 22648 BLOOD DONOR RONALD WALKER ......................................................................................... 22696 BUDGET ESTIMATES AND RELATED PAPERS ....................................................................... 22688 BUSINESS OF THE HOUSE ................................................................................... 22634, 22657, 22666 CASULA FUNCTION CENTRE ................................................................................................... 22701 CENTRAL TO EVELEIGH RAIL CORRIDOR PROJECT ............................................................ 22675 COMMITTEE ON COMMUNITY SERVICES .............................................................................. 22664 COMMUNITY RECOGNITION STATEMENTS ......................................................................... -

Victoria New South Wales

Victoria Legislative Assembly – January Birthdays: - Ann Barker - Oakleigh - Colin Brooks – Bundoora - Judith Graley – Narre Warren South - Hon. Rob Hulls – Niddrie - Sharon Knight – Ballarat West - Tim McCurdy – Murray Vale - Elizabeth Miller – Bentleigh - Tim Pallas – Tarneit - Hon Bronwyn Pike – Melbourne - Robin Scott – Preston - Hon. Peter Walsh – Swan Hill Legislative Council - January Birthdays: - Candy Broad – Sunbury - Jenny Mikakos – Reservoir - Brian Lennox - Doncaster - Hon. Martin Pakula – Yarraville - Gayle Tierney – Geelong New South Wales Legislative Assembly: January Birthdays: - Hon. Carmel Tebbutt – Marrickville - Bruce Notley Smith – Coogee - Christopher Gulaptis – Terrigal - Hon. Andrew Stoner - Oxley Legislative Council: January Birthdays: - Hon. George Ajaka – Parliamentary Secretary - Charlie Lynn – Parliamentary Secretary - Hon. Gregory Pearce – Minister for Finance and Services and Minister for Illawarra South Australia Legislative Assembly January Birthdays: - Duncan McFetridge – Morphett - Hon. Mike Rann – Ramsay - Mary Thompson – Reynell - Hon. Carmel Zollo South Australian Legislative Council: No South Australian members have listed their birthdays on their website Federal January Birthdays: - Chris Bowen - McMahon, NSW - Hon. Bruce Bilson – Dunkley, VIC - Anna Burke – Chisholm, VIC - Joel Fitzgibbon – Hunter, NSW - Paul Fletcher – Bradfield , NSW - Natasha Griggs – Solomon, ACT - Graham Perrett - Moreton, QLD - Bernie Ripoll - Oxley, QLD - Daniel Tehan - Wannon, VIC - Maria Vamvakinou - Calwell, VIC - Sen. -

Provision of Expert Opinion Concerning the Adverse Impacts of Wind Turbine Noise Truenergy Renewable Developments V Goyder Regional Council , a W Coffey & H Dunn

The Waubra Foundation. PO Box 7112 Banyule Vic 3084 Australia Reg. No. A0054185H ABN: 65 801 147 788 Patron Alby Schultz 14th April, 2014 Board Charlie Arnott, B. RuSci (Hons) Tony Hodgson, AM Sarah Laurie, BMBS (Flinders) (CEO) Mr A N Abbott Peter R. Mitchell AM, B.ChE (Chair) Piper Alderman Alexandra Nicol, B.Ag (Hons) GPO Box 65 Kathy Russell, B.Com, CA Adelaide SA 5001 The Hon. Clive Tadgell, AO The Hon. Dr. Michael Wooldridge, B.Sc. MBBS, MBA Provision of Expert Opinion concerning the Adverse Impacts of Wind Turbine Noise TruEnergy Renewable Developments v Goyder Regional Council , A W Coffey & H Dunn Dear Mr Abbott, I confirm that I have been provided with practice direction 5.4 relating to Expert Witnesses (Rule 160), and that I have read it and understood it. I have been asked by you to provide a report to address the following question: “Will noise or other direct or indirect consequences (and which consequences) of the operation of the Stony Gap wind farm erected as contemplated in the Application, and involving turbines of the type and dimensions referred to in the Application, in your opinion be likely to cause adverse health effects or significantly exacerbate existing adverse health effects to a significant percentage of the population living within up to 10 kilometers of the turbines from the Stony Gap Wind Farm?” In my opinion, it is inevitable that this proposed wind development, if built in this location with turbines of the specified size, will cause serious harm to the physical and mental health of a significant percentage of the surrounding population, including particularly to vulnerable groups such as young children, the elderly, and those with pre existing medical and psychiatric conditions, who live and work in the sound energy impact zone of this proposed Stony Gap Wind Farm (SGWF), out to a distance of at least 10 kilometers from the turbines, over the lifetime of the project. -

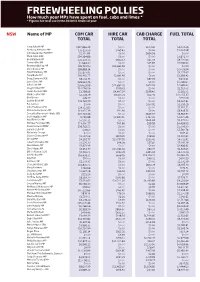

Freewheeling Pollies How Much Your Mps Have Spent on Fuel, Cabs and Limos * * Figures for Total Use in the 2010/11 Financial Year

FREEWHEELING POLLIES How much your MPs have spent on fuel, cabs and limos * * Figures for total use in the 2010/11 financial year NSW Name of MP COM CAR HIRE CAR CAB CHARGE FUEL TOTAL TOTAL TOTAL TOTAL Tony Abbott MP $217,866.39 $0.00 $103.42 $4,559.36 Anthony Albanese MP $35,123.59 $265.43 $0.00 $1,394.98 John Alexander OAM MP $2,110.84 $0.00 $694.56 $0.00 Mark Arbib SEN $34,164.86 $0.00 $0.00 $2,806.77 Bob Baldwin MP $23,132.73 $942.53 $65.59 $9,731.63 Sharon Bird MP $1,964.30 $0.00 $25.83 $3,596.90 Bronwyn Bishop MP $26,723.90 $33,665.56 $0.00 $0.00 Chris Bowen MP $38,883.14 $0.00 $0.00 $2,059.94 David Bradbury MP $15,877.95 $0.00 $0.00 $4,275.67 Tony Burke MP $40,360.77 $2,691.97 $0.00 $2,358.42 Doug Cameron SEN $8,014.75 $0.00 $87.29 $404.41 Jason Clare MP $28,324.76 $0.00 $0.00 $1,298.60 John Cobb MP $26,629.98 $11,887.29 $674.93 $4,682.20 Greg Combet MP $14,596.56 $749.41 $0.00 $1,519.02 Helen Coonan SEN $1,798.96 $4,407.54 $199.40 $1,182.71 Mark Coulton MP $2,358.79 $8,175.71 $62.06 $12,255.37 Bob Debus $49.77 $0.00 $0.00 $550.09 Justine Elliot MP $21,762.79 $0.00 $0.00 $4,207.81 Pat Farmer $0.00 $0.00 $177.91 $1,258.29 John Faulkner SEN $14,717.83 $0.00 $0.00 $2,350.51 Mr Laurie Ferguson MP $14,055.39 $90.91 $0.00 $3,419.75 Concetta Fierravanti-Wells SEN $20,722.46 $0.00 $649.97 $3,912.97 Joel Fitzgibbon MP 9,792.88 $7,847.45 $367.41 $2,675.46 Paul Fletcher MP $7,590.31 $0.00 $464.68 $2,475.50 Michael Forshaw SEN $13,490.77 $95.86 $98.99 $4,428.99 Peter Garrett AM MP $39,762.55 $0.00 $0.00 $1,009.30 Joanna Gash MP $78.60 $0.00 -

KABAILA P03 Sound Recordings Collected by Peter Rimas Kabaila

Finding aid KABAILA_P03 Sound recordings collected by Peter Rimas Kabaila, 1993-1999 Prepared July 2015 by RS Last updated 6 December 2016 ACCESS Availability of copies Listening copies are available. Contact the AIATSIS Audiovisual Access Unit by completing an online enquiry form or phone (02) 6261 4212 to arrange an appointment to listen to the recordings or to order copies. Restrictions on listening Some materials in this collection are restricted and may only be listened to by those who have obtained permission from the relevant Indigenous individual, family or community. Refer to audition sheets below for more details. Restrictions on use This collection is partially restricted. It contains some materials which may only be copied by those who have obtained permission from the relevant Indigenous individual, family or community. Refer to audition sheets below for more details. Permission must be sought from the relevant Indigenous individual, family or community for any publication or quotation of this material. Any publication or quotation must be consistent with the Copyright Act (1968). SCOPE AND CONTENT NOTE Date: 1993-1999 Extent: 55 audio-cassettes Production history These oral history recordings were collected between 1993 and 1999 during interviews conducted by archaeologist/architect Peter Kabaila who travelled to various places in New South Wales, the Australian Capital Territory, and Victoria. Interviewees include Sibby Johnson, Esther Cutmore, Ethel Baxter, Elma Pearsall, Christine Sloane, Josie Ingram, Susan Hart, Barbara -

House of Representatives

COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA Official Committee Hansard HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES STANDING COMMITTEE ON FAMILY AND COMMUNITY AFFAIRS Reference: Indigenous health FRIDAY, 25 JUNE 1999 CANBERRA BY AUTHORITY OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES INTERNET The Proof and Official Hansard transcripts of Senate committee hearings, some House of Representatives committee hearings and some joint committee hearings are available on the Internet. Some House of Representatives committees and some joint committees make available only Official Hansard transcripts. The Internet address is: http://www.aph.gov.au/hansard To search the parliamentary database, go to: http://search.aph.gov.au HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES STANDING COMMITTEE ON FAMILY AND COMMUNITY AFFAIRS Friday, 25 June 1999 Members: Mr Wakelin (Chair), Mr Andrews, Mr Edwards, Ms Ellis, Mrs Elson, Ms Hall, Mrs De-Anne Kelly, Dr Nelson, Mr Quick, Mr Schultz and Mr Wakelin Supplementary members: Mr Jenkins and Mr Nugent Members in attendance: Mr Edwards, Ms Ellis, Mrs Elson, Ms Hall, Mr Jenkins, Dr Nelson, Mr Nugent, Mr Quick, Mr Schultz and Mr Wakelin Terms of reference for the inquiry: In view of the unacceptably high morbidity and mortality of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, the House of Representatives Standing Committee on Family and Community Affairs was requested, during the Thirty-Eighth Parliament, to conduct an inquiry into Indigenous Health. The Committee was unable to complete its work due to the dissolution of the House of Representatives on 30 August 1998. Consequently, the Committee -

Dinner with Gladys Berejiklian Mp

Castlecrag Branch DINNER WITH GLADYS BEREJIKLIAN MP "STATE OF THE STATE REPORT" Date: Wednesday, 29th March Time: 7pm for 7.30pm Cost: $65 per person, $50 YLs Private Dining Room, NSW Parliament House, Macquarie Street Sydney Enquiries: Denise Fischer 02 9958 8452 Greenwich Branch LUNCHEON WITH ANTHONY ROBERTS MEMBER FOR LANE COVE Date: Wednesday, 29th March Time: 12noon Cost: $45 two course luncheon Strangers Dining Room, NSW Parliament House, Macquarie Street Sydney Enquiries: Joan Robinson 02 9439 6745 BREAKFAST WITH TONY & MARGIE ABBOTT MEMBER FOR WARRINGAH MINISTER FOR HEALTH AND AGEING Date: Friday, 31st March Time: 7am Cost: $25 Deck 32 Restaurant, Dee Why Beach Bookings 9977 6411 The Forestville – Killarney Heights presents: “AT HOME” WITH HON TONY & MARGIE ABBOTT Date: Friday, 31st March Time: 7pm Cost: $40 Belrose Bowling Club Bookings Helen Claringbold 9977 6411 Davidson State Electorate Conference INVITATION TO THE HOME OF ANDREW & VICKI HUMPHERSON End of Daylight Saving Cocktail Party Date: Saturday, 1st April Time: 4pm to 6.30pm Cost: $40 per person 51 Corymbia Circuit, Oxford Falls RSVP: 29th March [email protected] Berowra Branch BYO BEER AND BURGERS DAY Date: Sunday, 2nd April Time: 12.30pm (weather permitting) Berowra Waters Park, Western Side of Berowra Waters LOOK for the Liberal Tablecloth RSVP: Vanessa Crago 02 9456 3620 [email protected] Northbridge Branch AUTUMN COCKTAIL PARTY With Gladys Berejiklian MP Member for Willoughby Date: Sunday, 2nd April Time: 5pm to 7pm Cost: $35 4 Byora Crescent, Northbridge RSVP: Helen Gulson 02 9958 6573 [email protected] Picnic Point Young Liberals DINNER AT PARLIAMENT HOUSE With Hon.