Reflections from Case-Studies of Street Vendors in Delhi

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Maintaining Diversity of Integrated Rice and Fish Production Confers Adaptability of Food Systems to Global Change

REVIEW published: 09 November 2020 doi: 10.3389/fsufs.2020.576179 Maintaining Diversity of Integrated Rice and Fish Production Confers Adaptability of Food Systems to Global Change Sarah Freed 1*, Benoy Barman 2, Mark Dubois 3, Rica Joy Flor 4, Simon Funge-Smith 5, Rick Gregory 6, Buyung A. R. Hadi 4, Matthias Halwart 7, Mahfuzul Haque 2, S. V. Krishna Jagadish 8, Olivier M. Joffre 9, Manjurul Karim 3, Yumiko Kura 1, Matthew McCartney 10, Manoranjan Mondal 11, Van Kien Nguyen 12,13, Fergus Sinclair 14,15, Alexander M. Stuart 16, Xavier Tezzo 3,17, Sudhir Yadav 18 and Philippa J. Cohen 19 1 WorldFish, Phnom Penh, Cambodia, 2 WorldFish, Dhaka, Bangladesh, 3 WorldFish, Yangon, Myanmar, 4 Sustainable Impact Platform, International Rice Research Institute, Phnom Penh, Cambodia, 5 Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Bangkok, Thailand, 6 Independent Consultant, Yangon, Myanmar, 7 Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Rome, Italy, 8 Kansas State University, Manhattan, KS, United States, 9 Agence Française de Développement, Phnom Penh, Cambodia, 10 International Water Management Institute, Colombo, Sri Lanka, 11 Sustainable Impact Platform, Edited by: International Rice Research Institute, Dhaka, Bangladesh, 12 An Giang University, Vietnam National University, Ho Chi Minh Barbara Gemmill-Herren, City, Vietnam, 13 Fenner School of Environment & Society, The Australian National University, Canberra, ACT, Australia, Prescott College, United States 14 World Agroforestry (International Centre for Research in Agroforestry, ICRAF), Nairobi, Kenya, 15 School of Natural 16 Reviewed by: Sciences, Bangor University, Wales, United Kingdom, Sustainable Impact Platform, International Rice Research Institute, 17 18 Didier Bazile, Bogor, Indonesia, Environmental Policy Group, Wageningen University, Wageningen, Netherlands, Sustainable Impact 19 Institut National de la Recherche Platform, International Rice Research Institute, Los Banos, Philippines, WorldFish, Penang, Malaysia Agronomique (INRA), France Luis F. -

Curriculum Vitae

CURRICULUM VITAE PANHAVUTH SEM Address: Wat Phnom Commune, Doun Penh District, Phnom Penh, Cambodia Tel: (855)12 545 334 E-mail: [email protected] Personal Information Sex : Male Marital status : Single Date of Birth : May 05, 1983 Place of birth : Battambang province Nationality : Cambodian Languages : Khmer - mother tongue English - Fluent Education Background 2001- 2005 : Graduated Bachelor Degree in Computer Science Royal University of Phnom Penh (RUPP), Phnom Penh, Cambodia 1998-2000 : Wat Koh High School Other Training .2 nd – 4th June 2008 Attended Workshop on Road Safety for Venerable Road User in Vientiane, Lao PDR. 3rd November 2008 Attended Workshop on Injury Prevention in Hanoi, Vietnam. 4th – 6th November 2008 Attended the Second ASIA Pacific Conference on Injury Prevention, Hanoi, Vietnam. 16 th – 17 th September 2009 Attended 4 th IRTAD Conference on Data collection and analysis for target setting and monitoring performance and progress, Seoul, Republic of Korea. 16 th – 17 th December 2009 Attended Workshop on Issues of Data Collection for Road Safety, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. 28 th – 30 th March 2010 Attended Road Safety on Four Continents Conference in Abu Dhabi, UAE. Work Experience 2005- Present Road Crash and Victim Information System Manager 5 years as a project manager of Road Crash and Victim Information System Manager of Handicap International Belgium, to implement database management system in Cambodia through data collection from police and health. I have been managing project activities, monitoring and evaluation, planning, financial management, partner relation, data analysis and reporting. I have introduced the Global Positioning System for traffic police integrated with the database management system by using GIS software in Cambodia. -

Recruitment Guide INTERNATIONAL SCHOOL of PHNOM PENH PHNOM PENH, CAMBODIA

Recruitment Guide INTERNATIONAL SCHOOL OF PHNOM PENH PHNOM PENH, CAMBODIA ispp.edu.kh ispp.edu.kh 1 What if you could enjoy the benefits of living in beautiful Cambodia and working at a world-class international school? The International School of Phnom Penh (ISPP) is a co-educational not-for-profit English medium day school enrolling students from Early Years (age 3) through to Grade 12. The school is housed at a new, purpose-built campus in a fast growing area of the city. Our School History In 1989, ISPP was formed by a group of families that worked the IB Diploma, and the Middle Years Programme followed in for non-governmental organisations. The first six students 2001. In 2004, the Primary Years Programme was authorised, met part-time in the home of a parent who was also the making ISPP a fully accredited, three programme IB World teacher. In 1990, in a rented villa, ISPP took the first real steps School. ISPP is also accredited by both the Western Associa- to become a normal day school, with a curriculum and a tion of Schools and Colleges (WASC) (USA) and the Council Kindergarten to Grade 4 programme set in place. Student of International Schools (CIS) (Europe). numbers increased to 11 and the school’s Charter was written and approved, establishing it as a parent-owned and In November 2015, ISPP was awarded full re-accreditation operated, non-sectarian, non-profit school. status with CIS/WASC and full re-authorisation of all three IB programmes. In 1995, the school was licensed by the Cambodian Ministry of Education, Youth and Sport. -

Indonesia: Travel Advice MANILA

Indonesia: Travel Advice MANILA B M U M KRUNG THEP A R (BANGKOK) CAMBODIA N M T International Boundary A E Medan I PHNOM PENH V Administrative Boundary 0 10 miles Andaman National Capital 0 20 km Sea T Administrative Centre H South A SUMATERA PHILIPPINES Other Town I L UTARA A Major Road N D China Sea MELEKEOKRailway 0 200 400 miles Banda Aceh Mount Sinabung 0 600 kilometres BANDAR SERI BEGAWAN A Langsa BRUNEI I ACEH MALAYSIA S Celebes Medan Y KALIMANTAN A Tarakan KUALA LUMPUR UTARA Pematangsiantar L Tanjung Selor SeaSULAWESI A UTARA PACIFIC SUMATERA M Tanjungredeb GORONTALO Dumai UTARA SINGAPORE Manado SINGAPORE Tolitoli Padangsidempuan Tanjungpinang Sofifi RIAU Pekanbaru KALIMANTAN OCEAN Nias Singkawang TIMUR KEPULAUAN Pontianak Gorontalo Sumatera RIAU Borneo Payakumbuh KALIMANTAN Samarinda SULAWESI Labuha Manokwari Padang (Sumatra) BARAT TENGAH KEPULAUAN Palu MALUKU Sorong SUMATERA Jambi BANGKA BELITUNG KALIMANTAN Maluku Siberut Balikpapan UTARA PAPUA BARAT TENGAH Sulawesi BARAT JAMBI Pangkalpinang Palangkaraya SULAWESI Sungaipenuh Ketapang BARAT Bobong (Moluccas) Jayapura SUMATERA Sampit (Celebes) SELATAN KALIMANTAN Mamuju Namlea Palembang SELATAN Seram Bula Lahat Prabumulih Banjarmasin Majene Bengkulu Kendari Ambon PAPUA Watampone BENGKULU LAMPUNG INDONESIA Bandar JAKARTA Java Sea Makassar New Lampung JAKARTA SULAWESI Banda JAWA TENGAH SULAWESI MALUKU Guinea Serang JAWA TIMUR SELATAN TENGGARA Semarang Kepulauan J Sumenep Sea Aru PAPUA BANTEN Bandung a w a PAPUA ( J a v Surabaya JAWA a ) NUSA TENGGARA Lumajang BALI BARAT Kepulauan -

1 “Land Sharing in Phnom Penh and Bangkok: Lessons from Four

“Land Sharing in Phnom Penh and Bangkok: Lessons from Four Decades of Innovative Slum Redevelopment Projects in Two Southeast Asian „Boom Towns‟” Author: Paul E. Rabé 1 Affiliation: University of Southern California, School of Policy, Planning and Development, Abstract: In 2003 Cambodian authorities launched four pilot slum upgrading projects in the capital city of Phnom Penh using the technique of “land sharing.” The projects aimed to attract private development on lands occupied by slum dwellers, and to move the slum dwellers into new housing on site using cross-subsidies from commercial development. This paper identifies the inadequate institutional support structure for land sharing in Phnom Penh as the main reason why these projects had only very limited success as slum upgrading instruments. It contrasts this with the more successful land sharing experience in Bangkok during the 1970s and 1980s. *Paul Rabé’s paper was awarded an Honorable Mention in the “Places We Live” research paper competition held by the International Housing Coalition (IHC), USAID, The World Bank, Cities Alliance, and the Woodrow Wilson Center’s Comparative Urban Studies Program (CUSP). This paper was presented at the “Places We Live: Slums and Urban Poverty in the Developing World” policy workshop in Washington, DC on April 30, 2010. 1 1. Announcing Four Land Sharing Pilot Projects In 2003 public authorities in Cambodia introduced an innovative model of urban redevelopment and slum upgrading through the technique of “land sharing.” The Council of Ministers identified four pilot projects in the center of the capital city of Phnom Penh—with a combined population estimated at 17,348—where slum residents would be re-housed on site in new housing which they would obtain for free, as part of the government’s “social land concession principles.”2 The new housing was to be financed entirely by private developers in the form of cross-subsidies from commercial development on another portion of the same site. -

Danish Ambassador Rides from Bangkok to Phnom Penh to Raise Money for Child Helmets

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Danish Ambassador rides from Bangkok to Phnom Penh to raise money for child helmets February 17, 2012 – Phnom Penh On February 17th, motorcyclists including Danish Ambassador to Cambodia Mikael Hemniti Winther arrived in Phnom Penh after driving from Bangkok in the Go4 Charity Ride. This trip raised funds for a 7 month school-based road safety program called Helmets for Kids which is being run by the non-profit AIP Foundation. A launching ceremony will congratulate the bikers and kick-off the school program. With 1,816 deaths on the road in 2010, the numbers of road traffic crashes in Cambodia is swiftly becoming a major cause for concern. Particularly alarming is the fact that 72 percent of crashes are caused by motorcycles, yet preliminary research shows that only about 8 percent of passengers— including children— wear helmets. “The results of this phenomenon will continue to be disastrous to the country’s youth, and cost Cambodiaan estimated 279 million USD per year, if nothing is done,” said Mirjam Sidik, AIP Foundation’s Executive Director. “The Go4 Charity Ride is one example of how successful a partnership between private sector firms, individual activities, and non-profit organizations can be.” The government of Cambodia also endorsed child helmet use by joining representatives from these groups at the Helmets for Kids launching event held at the Hotel Cambodiana. Road safety is one of the government’s main priorities, particularly in the second year of the United Nations’ Decade of Action for Road Safety (2011-2020). "I would like to deeply thank the Kingdom of Denmark and Go4 Charity Riders for sponsoring this program," said H.E Poeu Maly, Deputy Secretary General of the National Road Safety Committee. -

7. Satellite Cities (Un)Planned

Articulating Intra-Asian Urbanism: The Production of Satellite City Megaprojects in Phnom Penh Thomas Daniel Percival Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Leeds, School of Geography August 2012 ii The candidate confirms that the work submitted is his/her own, except where work which has formed part of jointly authored publications has been included. The contribution of the candidate and the other authors to this work has been explicitly indicated below1. The candidate confirms that appropriate credit has been given within the thesis where reference has been made to the work of others. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. © 2012, The University of Leeds, Thomas Daniel Percival 1 “Percival, T., Waley, P. (forthcoming, 2012) Articulating intra-Asian urbanism: the production of satellite cities in Phnom Penh. Urban Studies”. Extracts from this paper will be used to form parts of Chapters 1-3, 5-9. The paper is based on my primary research for this thesis. The final version of the paper was mostly written by myself, but with professional and editorial assistance from the second author (Waley). iii Acknowledgements First and foremost, I would like to thank my supervisors, Sara Gonzalez and Paul Waley, for their invaluable critiques, comments and support throughout this research. Further thanks are also due to the members of my Research Support Group: David Bell, Elaine Ho, Mike Parnwell, and Nichola Wood. I acknowledge funding from the Economic and Social Research Council. -

Funshop Brochure

young leaders making real changethrough sport The Youth and Sport Task Force represents creative, passionate and innovative young leaders across Asia and the Pacific who use sport as a tool for positive social change in their communities. These young leaders are using sport to make a difference: to empower young women and girls, to promote tolerance, to counter extremism, to reach out to the vulnerable and marginalized, to educate The about the environment, to promote the values of respect, empathy, and fairness – the list goes on! Ultimately, they are using sport as a universal force for good. In other words, the Task Force and its Youth Members Youth are using sport to contribute to the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals. The youth are in control. They design their own programmes, determine their own priorities and and collectively, decide on the strategic direction of the Task Force. UNESCO supports the Task Force by providing opportunities for the members to promote and enhance their work by connecting with each other and with regional and global opportunities for Sport growth and capacity building. Want to experience how? Join us for 2019 Funshop of Sport and SDGs in Seoul, Republic of Korea on 5-8 September! Task www.youthandsport.org 2 Force Sport and the Sustainable Development The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development explicitly acknowledges the potential for sport to be an enabler of the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). In addition to bringing Goals significant psychosocial and physical benefits for individuals, sport can also unite, engage and mobilize diverse populations towards a common goal. -

MEXICO UNITED STATES / CANADA Learn More About Rosewood at Rosewoodhotels.Com MEXICO CARIBBEAN / ATLANTIC

UNITED STATES / CANADA Opening Winter 2018 ROSEWOOD ROSEWOOD ROSEWOOD THE CARLYLE, A ROSEWOOD MANSION ON SAND HILL® MIRAMAR BEACH ROSEWOOD HOTEL CORDEVALLE TURTLE CREEK® MONTECITO DALLAS, TX MENLO PARK, CA MONTECITO, CA NEW YORK, NY SAN MARTIN, CA USA USA USA USA USA MEXICO ROSEWOOD INN ROSEWOOD ROSEWOOD LAS VENTANAS AL ROSEWOOD OF THE ANASAZI® HOTEL GEORGIA WASHINGTON D.C. PARAÍSO, A PUEBLA ROSEWOOD RESORT SANTA FE, NM VANCOUVER, B.C. WASHINGTON, D.C. LOS CABOS PUEBLA USA CANADA USA MEXICO MEXICO MEXICO CARIBBEAN / ATLANTIC Opening Winter 2019 ROSEWOOD ROSEWOOD ROSEWOOD ROSEWOOD ROSEWOOD MAYAKOBA SAN MIGUEL BERMUDA BAHA MAR LITTLE DIX BAY® DE ALLENDE® VIRGIN GORDA, RIVIERA MAYA SAN MIGUEL HAMILTON PARISH NASSAU BRITISH VIRGIN MEXICO DE ALLENDE, MEXICO BERMUDA THE BAHAMAS ISLANDS Learn more about Rosewood at rosewoodhotels.com EUROPE MIDDLE EAST Opening Summer 2018 ROSEWOOD HÔTEL DE CRILLON, ROSEWOOD ROSEWOOD ROSEWOOD LONDON A ROSEWOOD HOTEL CASTIGLION DEL ABU DHABI JEDDAH BOSCO LONDON PARIS TUSCANY ABU DHABI, JEDDAH UNITED KINGDOM FRANCE ITALY UNITED ARAB EMIRATES SAUDI ARABIA ASIA Opening Winter 2018 Opening Winter 2018 Opening Winter 2018 ROSEWOOD ROSEWOOD ROSEWOOD ROSEWOOD ROSEWOOD BEIJING BANGKOK PHNOM PENH GUANGZHOU HONG KONG BEIJING BANGKOK PHNOM PENH GUANGZHOU HONG KONG SAR CHINA THAILAND CAMBODIA CHINA CHINA COMING SOON 2019 & 2020 ROSEWOOD SÃO PAULO (2019) SÃO PAULO, BRAZIL ROSEWOOD HOI AN (2019) HOI AN, VIETNAM OpeningROSEWOOD Summer 2018 MANDARINA (2020) RIVIERA NAYARIT, MEXICO ROSEWOOD ROSEWOOD ROSEWOOD ROSEWOOD PUERTO PAPAGAYO (2020) LUANG PRABANG PHUKET SANYA PAPAGAYO, COSTA RICA LUANG PRABANG PHUKET SANYA ROSEWOOD EDINBURGH (2020) LAOS THAILAND CHINA EDINBURGH, SCOTLAND Rosewood is about creating personal journeys and discovery for our guests. -

Garment Worker Diaries the Lives and Wages

1 3 GARMENT WORKER DIARIES 4 BANGALORE, INDIA THE LIVES AND WAGES OF [1] It’s 1:15pm in Bangalore, one garment worker sits with her cousins, styling each other’s hair. GARMENT WORKERS [2] One garment worker’s home in Ramangara, Bangalore. [3] A garment worker does all the household chores on her one day off each week. Several women have given permission [4] A garment worker's kids are An intimate look into cleaning fish for a meal in Bidadi, to share photos of their home life as part Bangalore. [5] In the evening, a the daily lives of women of this yearlong research study. We hope garment worker and her sister write from the Garment this helps the world to better understand down their expenses in her Financial Diary, as part of the project. Worker Diaries project in what it’s like to be a garment worker and inspires you to become an advocate for BANGALORE, INDIA Cambodia and India. the people who make your clothes. 5 2 26 10 11 7 8 PHNOM PENH, CAMBODIA PHNOM PENH, CAMBODIA 12 13 [7] This woman, one of the workers in the Diaries project, lives in Kampong Speu Province, just outside Phnom Penh. [8] On her one day off each week, she cooks a big lunch, such as fish soup with rice and fruit relish. [9] She also does all the household chores. [10] On Sunday another garment worker chills at home and watches TV with her kids, just like everybody else! [11] Another worker stands in her kitchen area where she’s making a big feast. -

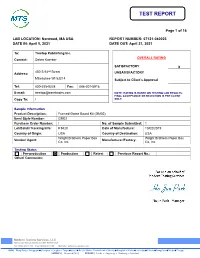

LAB LOCATION: Norwood, MA USA REPORT NUMBER: 67121-040023 DATE IN: April 5, 2021 DATE OUT: April 21, 2021

TEST REPORT Page 1 of 16 LAB LOCATION: Norwood, MA USA REPORT NUMBER: 67121-040023 DATE IN: April 5, 2021 DATE OUT: April 21, 2021 To: Treetop Publishing Inc. OVERALL RATING Contact: Debra Koerber SATISFACTORY X 450 S 92nd Street Address: UNSATISFACTORY Milwaukee WI 53214 Subject to Client’s Approval Tel: 800-255-9228 Fax: 888-201-5916 E-mail: [email protected] NOTE: RATING IS BASED ON TESTING LAB RESULTS. FINAL ACCEPTANCE OR REJECTION IS PER CLIENT ONLY. Copy To: / Sample Information Product Description: Framed Game Board Kit (GM02) Item/ Style Number: GM02 Purchase Order Number: / No. of Sample Submitted: 1 Lot/Batch/Tracking Info: # 9420 Date of Manufacture: 10/02/2019 Country of Origin: USA Country of Destination: USA Wright Brothers Paper Box Wright Brothers Paper Box Vendor/ Agent: Manufacturer/Factory: Co, Inc Co, Inc Testing Status Pre-production Production Retest Previous Report No.: Other/ Comments: Modern Testing Services, LLC 349 Lenox Street, Norwood, MA 02062 USA Tel: (508)-638-1793 Fax: (508-638-1759 Website: www.mts-global.com ASIA ▏Hong Kong˙Dongguan˙Shanghai˙Qingdao˙Taipei˙Seoul˙Ho Chi Minh˙Phnom Penh˙Jakarta˙Bangkok˙Dhaka˙Colombo˙Lahore˙Bangalore˙Noida˙Tirupur AMERICA ▏Norwood (MA) EUROPE ▏Leeds ˙ Augsburg ˙ Hamburg ˙ Istanbul TEST REPORT Page 2 of 16 Report Number: 67121-040023 Sample Photos Modern Testing Services, LLC 349 Lenox Street, Norwood, MA 02062 USA Tel: (508)-638-1793 Fax: (508-638-1759 Website: www.mts-global.com ASIA ▏Hong Kong˙Dongguan˙Shanghai˙Qingdao˙Taipei˙Seoul˙Ho Chi Minh˙Phnom Penh˙Jakarta˙Bangkok˙Dhaka˙Colombo˙Lahore˙Bangalore˙Noida˙Tirupur -

LRC Brochure Final Version.Pmd

mCÄmNÐlsikSaRsavRCav CakEnøgpþl;cMeNHdwg nig B½t’manBIRbeTsmhaGnutMbn;emKgÁ1 (GMS) nig skmµPaBnanarbs; FnaKarGPivDÁÇn_GasIuenAkm<úCa. mCÄmNÐl ebIkcMhCasaFarN³ nig manbNaÑl½yRbmUlpþúMnUvÉksare)aHBumÖpSay nig ÉksarnanaCaeGLicRtUnic GuineFINit nig brikçarsMrab;eFVIsnñisITtamvIedGUsMrab;KMerag PPP kñúgkarerobcMkmµviFIsikSa nig karBiPakSaelIkarRKb;RKgkarGPivDÆn_enAkñúgRbeTsmhaGnutMbn;emKgÁ. mCÄmNÐlsikSaRsavRCavmanpþl;CUn³ esovePA nig Éksare)aHBumÖnanarbs;FnaKarGPivDÆn_GasIu RbeTs PPP KWCaKMeragpþÜcepþImGPivDÆn_ FnFanmnusSkñúgtMbn;mYyEdl mhaGnutMbn;emKgÁ RbeTsenAkñúgtMbn;Gas‘an nig RbeTskm<úCa. ]btßmÖeday FnaKarGPivDÆn_GasIutamry³mUlniFiBiess esvakmµx©IesovePAk¾manpþl;CUndl;GñkGansMrab;ry³eBl énCMnYYybec©keTs. Pñak;garNUEvlesLg;sMrab;karGPivDÆn_ mYyGaTitü. GnþrCati RksYgkarbreTsénsaFarN³rdæ)araMg nig mUlniFikat;bnßyPaBRkIRk nig shRbtibtþikarkñúgtMbn;rbs; kMBüÚT½redIm,IEsVgrkB½t’mannanaTak;TgnwgkarGPivDÆn_ B½t’manEdl RbeTscin k¾)anpþl;CaCMnYybec©keTspgEdr. KMeragenH Gacrk)anenAkñúgRbB½n§Tinñn½yrbs; FnaKarGPivDÆn_GasIu RbeTs KWCaEpñkmYyd¾sMxan;én kmµviFIshRbtibtþikaresdækic©enA The Phnom Penh Plan mhaGnutMbn;emKgÁnig RbBn½§Tinñn½ynanaTak;TgnwgkarGPivDÆn_. mhaGnutMbn;emKgÁ. Learning Resource Center Éksarpþl;CUneday\tKitéfø CaEpñkmYyénesvakmµEckcayB½t’man Phnom Penh Plan (PPP) Secretariat Open to the public rbs;mCÄmNÐl. Asian Development Bank 6th Floor, Mekong Department Monday–Friday ÉksarTak;TgnwgkmµviFIsikSarbs;KMerag PPP sþIBIeKalneya)ay 6 ADB Avenue, Mandaluyong City 8:30 am–12:00 pm and 1:30 pm–5:00 pm 1550 Metro Manila, Philippines saFarN³