Working-Class Housing in Barrow and Lancaster 1880-1930

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hundreds of Homes for Sale See Pages 3, 4 and 5

Wandsworth Council’s housing newsletter Issue 71 July 2016 www.wandsworth.gov.uk/housingnews Homelife Queen’s birthday Community Housing cheat parties gardens fined £12k page 10 and 11 Page 13 page 20 Hundreds of homes for sale See pages 3, 4 and 5. Gillian secured a role at the new Debenhams in Wandsworth Town Centre Getting Wandsworth people Sarah was matched with a job on Ballymore’s Embassy Gardens into work development in Nine Elms. The council’s Work Match local recruitment team has now helped more than 500 unemployed local people get into work and training – and you could be next! The friendly team can help you shape up your CV, prepare for interview and will match you with a live job or training vacancy which meets your requirements. Work Match Work They can match you with jobs, apprenticeships, work experience placements and training courses leading to full time employment. securing jobs Sheneiqua now works for Wandsworth They recruit for dozens of local employers including shops, Council’s HR department. for local architects, professional services, administration, beauti- cians, engineering companies, construction companies, people supermarkets, security firms, logistics firms and many more besides. Work Match only help Wandsworth residents into work and it’s completely free to use their service. Get in touch today! w. wandsworthworkmatch.org e. [email protected] t. (020) 8871 5191 Marc Evans secured a role at 2 [email protected] Astins Dry Lining AD.1169 (6.16) Welcome to the summer edition of Homelife. Last month, residents across the borough were celebrating the Queen’s 90th (l-r) Cllr Govindia and CE Nick Apetroaie take a glimpse inside the apartments birthday with some marvellous street parties. -

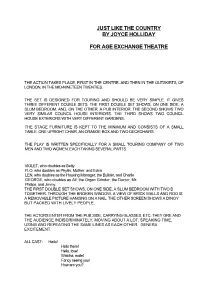

JLTC Playscript

JUST LIKE THE COUNTRY BY JOYCE HOLLIDAY FOR AGE EXCHANGE THEATRE THE ACTION TAKES PLACE, FIRST IN THE CENTRE, AND THEN IN THE OUTSKIRTS, OF LONDON, IN THE MID-NINETEEN TWENTIES. THE SET IS DESIGNED FOR TOURING AND SHOULD BE VERY SIMPLE. IT GIVES THREE DIFFERENT DOUBLE SETS. THE FIRST DOUBLE SET SHOWS, ON ONE SIDE, A SLUM BEDROOM, AND, ON THE OTHER, A PUB INTERIOR. THE SECOND SHOWS TWO VERY SIMILAR COUNCIL HOUSE INTERIORS. THE THIRD SHOWS TWO COUNCIL HOUSE EXTERIORS WITH VERY DIFFERENT GARDENS. THE STAGE FURNITURE IS KEPT TO THE MINIMUM AND CONSISTS OF A SMALL TABLE, ONE UPRIGHT CHAIR, AN ORANGE BOX AND TWO DECKCHAIRS. THE PLAY IS WRITTEN SPECIFICALLY FOR A SMALL TOURING COMPANY OF TWO MEN AND TWO WOMEN, EACH TAKING SEVERAL PARTS. VIOLET, who doubles as Betty FLO, who doubles as Phyllis, Mother, and Edna LEN, who doubles as the Housing Manager, the Builder, and Charlie GEORGE, who doubles as Alf, the Organ Grinder, the Doctor, Mr. Phillips, and Jimmy. THE FIRST DOUBLE SET SHOWS, ON ONE SIDE, A SLUM BEDROOM WITH TWO B TOGETHER. THROUGH THE BROKEN WINDOW, A VIEW OF BRICK WALLS AND ROO IS A REMOVABLE PICTURE HANGING ON A NAIL. THE OTHER SCREEN SHOWS A DINGY BUT PACKED WITH LIVELY PEOPLE. THE ACTORS ENTER FROM THE PUB SIDE, CARRYING GLASSES, ETC. THEY GRE AND THE AUDIENCE INDISCRIMINATELY, MOVING ABOUT A LOT, SPEAKING TIME, USING AND REPEATING THE SAME LINES AS EACH OTHER. GENERA EXCITEMENT. ALL CAST: Hello! Hello there! Hello, love! Watcha, mate! Fancy seeing you! How are you? How're you keeping? I'm alright. -

Historical and Contemporary Archaeologies of Social Housing: Changing Experiences of the Modern and New, 1870 to Present

Historical and contemporary archaeologies of social housing: changing experiences of the modern and new, 1870 to present Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the University of Leicester by Emma Dwyer School of Archaeology and Ancient History University of Leicester 2014 Thesis abstract: Historical and contemporary archaeologies of social housing: changing experiences of the modern and new, 1870 to present Emma Dwyer This thesis has used building recording techniques, documentary research and oral history testimonies to explore how concepts of the modern and new between the 1870s and 1930s shaped the urban built environment, through the study of a particular kind of infrastructure that was developed to meet the needs of expanding cities at this time – social (or municipal) housing – and how social housing was perceived and experienced as a new kind of built environment, by planners, architects, local government and residents. This thesis also addressed how the concepts and priorities of the Victorian and Edwardian periods, and the decisions made by those in authority regarding the form of social housing, continue to shape the urban built environment and impact on the lived experience of social housing today. In order to address this, two research questions were devised: How can changing attitudes and responses to the nature of modern life between the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries be seen in the built environment, specifically in the form and use of social housing? Can contradictions between these earlier notions of the modern and new, and our own be seen in the responses of official authority and residents to the built environment? The research questions were applied to three case study areas, three housing estates constructed between 1910 and 1932 in Birmingham, London and Liverpool. -

Birmingham City Council Report to Cabinet 14Th May 2019

Birmingham City Council Report to Cabinet 14th May 2019 Subject: Houses in Multiple Occupation Article 4 Direction Report of: Director, Inclusive Growth Relevant Cabinet Councillor Ian Ward, Leader of the Council Members: Councillor Sharon Thompson, Cabinet Member for Homes and Neighbourhoods Councillor John Cotton, Cabinet Member for Social Inclusion, Community Safety and Equalities Relevant O &S Chair(s): Councillor Penny Holbrook, Housing & Neighbourhoods Report author: Uyen-Phan Han, Planning Policy Manager, Telephone No: 0121 303 2765 Email Address: [email protected] Are specific wards affected? ☒ Yes ☐ No If yes, name(s) of ward(s): All wards Is this a key decision? ☒ Yes ☐ No If relevant, add Forward Plan Reference: 006417/2019 Is the decision eligible for call-in? ☒ Yes ☐ No Does the report contain confidential or exempt information? ☐ Yes ☒ No 1 Executive Summary 1.1 Cabinet approval is sought to authorise the making of a city-wide direction under Article 4 of the Town and Country Planning (General Permitted Development) (England) Order 2015. This will remove permitted development rights for the change of use of dwelling houses (C3 Use Class) to houses in multiple occupation (C4 Use Class) that can accommodate up to 6 people. 1.2 Cabinet approval is also sought to authorise the cancellation of the Selly Oak, Harborne and Edgbaston Article 4 Direction made under Article 4(1) of the Town and Country Planning (General Permitted Development) (England) Order 1995. This is to avoid duplication as the city-wide Article 4 Direction will cover these areas. Page 1 of 8 2 Recommendations 2.1 That Cabinet authorises the Director, Inclusive Growth to prepare a non- immediate Article 4 direction which will be applied to the City Council’s administrative area to remove permitted development rights for the change of use of dwelling houses (C3 use) to small houses in multiple occupation (C4 use). -

Final General Management Plan/Environmental Impact Statement, Mary Mcleod Bethune Council House National Historic Site

Final General Management Plan Environmental Impact Statement Mary McLeod Bethune Council House National Historic Site Washington, D.C. Final General Management Plan / Environmental Impact Statement _____________________________________________________________________________ Mary McLeod Bethune Council House National Historic Site Washington, District of Columbia The National Park Service is preparing a general management plan to clearly define a direction for resource preservation and visitor use at the Mary McLeod Bethune Council House National Historic Site for the next 10 to 15 years. A general management plan takes a long-range view and provides a framework for proactive decision making about visitor use, managing the natural and cultural resources at the site, developing the site, and addressing future opportunities and problems. This is the first NPS comprehensive management plan prepared f or the national historic site. As required, this general management plan presents to the public a range of alternatives for managing the site, including a preferred alternative; the management plan also analyzes and presents the resource and socioeconomic impacts or consequences of implementing each of those alternatives the “Environmental Consequences” section of this document. All alternatives propose new interpretive exhibits. Alternative 1, a “no-action” alternative, presents what would happen under a continuation of current management trends and provides a basis for comparing the other alternatives. Al t e r n a t i v e 2 , the preferred alternative, expands interpretation of the house and the life of Bethune, and the archives. It recommends the purchase and rehabilitation of an adjacent row house to provide space for orientation, restrooms, and offices. Moving visitor orientation to an adjacent building would provide additional visitor services while slightly decreasing the impacts of visitors on the historic structure. -

Birmingham City Council City Council a G E N

BIRMINGHAM CITY COUNCIL CITY COUNCIL TUESDAY, 10 JULY 2018 AT 14:00 HOURS IN COUNCIL CHAMBER, COUNCIL HOUSE, VICTORIA SQUARE, BIRMINGHAM, B1 1BB A G E N D A 1 NOTICE OF RECORDING Lord Mayor to advise that this meeting will be webcast for live or subsequent broadcast via the Council's Internet site (www.civico.net/birmingham) and that members of the press/public may record and take photographs except where there are confidential or exempt items. 2 DECLARATIONS OF INTERESTS Members are reminded that they must declare all relevant pecuniary and non pecuniary interests arising from any business to be discussed at this meeting. If a disclosable pecuniary interest is declared a Member must not speak or take part in that agenda item. Any declarations will be recorded in the minutes of the meeting. 3 MINUTES 5 - 86 To confirm and authorise the signing of the Minutes of the meeting of the Council held on 12 June 2018. 4 LORD MAYOR'S ANNOUNCEMENTS (1400-1410) To receive the Lord Mayor's announcements and such communications as the Lord Mayor may wish to place before the Council. 5 PETITIONS (15 minutes allocated) (1410-1425) To receive and deal with petitions in accordance with Standing Order 9. As agreed by Council Business Management Committee a schedule of outstanding petitions is available electronically with the published papers for the meeting and can be viewed or downloaded. Page 1 of 118 6 QUESTION TIME (90 minutes allocated) (1425-1555) To deal with oral questions in accordance with Standing Order 10.3 A. -

Bromley Borough Guide the Drive for Excellence in Management

THE LONDON BOROUGH f floor central 1, library, high street, bromley br1 1ex answering arts »halls your sports • zoos leisure nature trails »parks information holiday activities needs museums »libraries Leisureline THE LONDON BOROUGH L A creative service that is designed to understand problems and provide lasting solutions. t o liter a to c o rp o rate i d e n t it y 1. e/ H I If I 4 0 1 r r l j m ¡têt* vdu WORKER creative consultants has the right idea Rushmore 55 Tweedy Road, Bromley, Kent BRI 3NH Telephone 081-464 6380/6389 Fax 081-290 1053 YOUNGS FENCING IS OUR BUSINESS! looking for new fencing?, or advice how to fix the old one?, ... perhaps a new shed!! “THEN COME TO THE REAL EXPERTS”, whatever the problem, we’re sure we can solve it. TRAINED & EXPERIENCED SALES S T A F F > ^ ^ WAITING TO HELP YOU! AND AS A BONUS Mon-Fri 8 am-12.30 pm With our new Celbronze plant we can now provide all our fencing 1.30 pm-5.30 pm and sheds in a rich walnut shade, with the added bonus of pressure Sat 8 am-5 pm treated wood guaranteed for long life and with the backing of Rentokil expertise. SHEDS 10 DESIGNS FENCING SIZES TO YOUR ALL TYPES SPECIFICATION SUPPLY ONLY: FREE AND PROMPT DELIVERY SUPPLY AND ERECT: INSPECTIONS AND ESTIMATES FREE SEVENOAKS WAY, ST PAULS CRAY (NEXT TO TEXAS HOMECARE) ORPINGTON (0689) 826641 (5 LINES) FAX (0689) 878343 2 The Bromley Borough Guide The Drive for Excellence in Management ia— Bntish TELECOM A«» u It,.......a ‘.A. -

Estate Regeneration

ESTATE REGENERATION sourcebook Estate Regeneration Sourcebook Content: Gavin McLaughlin © February 2015 Urban Design London All rights reserved [email protected] www.urbandesignlondon.com Cover image: Colville Phase 2 Karakusevic Carson Architects 2 Preface As we all struggle to meet the scale and complexity of London’s housing challenges, it is heartening to see the huge number of successful estate regeneration projects that are underway in the capital. From Kidbrooke to Woodberry Down, Clapham Park to Graeme Park, South Acton to West Hendon, there are estates being transformed all across London. All are complicated, but most are moving ahead with pace, delivering more homes of all tenures and types, to a better quality, and are offering improved accommodation, amenities and environments for existing residents and newcomers alike. The key to success in projects as complex as estate regeneration lies in the quality of the partnerships and project teams that deliver them and, crucially, in the leadership offered by local boroughs. That’s why I welcome this new resource from UDL as a useful tool to help those involved with such projects to see what’s happening elsewhere and to use the networks that London offers to exchange best practice. Learning from the successes – and mistakes – of others is usually the key to getting things right. London is a fascinating laboratory of case studies and this new sourcebook is a welcome reference point for those already working on estate regeneration projects or those who may be considering doing so in the future. David Lunts Executive Director of Housing and Land at the GLA Introduction There is a really positive feeling around estate regeneration in London at the moment. -

Alias Age Occupation Interview Period Alec Edwards 40 Civil Servant April

Alias Age Occupation Interview Period Alec Edwards 40 Civil servant April 2012 Ben Bassett 37 Civil servant April 2012 Connor Kershaw 51 Civil servant April 2012 Daisy Mills (and her friend) 46 Civil servant April 2012 Evelyn McWilliams 41 Council administrator April 2012 Fred Toulson 68 School teacher April 2012 Georgina Harris 35 Clerk April 2012 Harriet Johnson (and her daughter) 83 Pensioner April 2012 Lexie Browning 23 Student April 2012 Jessi Bowen 27 Bartender April 2012 Kieran Turner 65 Pensioner April 2012 Lou Griffiths (and his wife) 59 Public official and unemployed April 2012 Maisie Drake 23 Homemaker April 2012 Norma Davies (and her friend) 63 Pensioner and activist April 2012 Ollie Marks 30 Laborer April 2012 Blake Johns 28 Tradesman April 2012 Ryan Sampson 39 Public official and May 2012 spokesperson Ashton Roberts 24 Artist May 2012 Joel Lopes 25 Pub worker May 2012 Sam Orwell 25 Unemployed May 2012 Toby McEwing 22 Betting shop manager May 2012 Nicki Josephs 22 Sales assistant May 2012 Nancy Pemberton 59 Pensioner and activist May 2012 Andy Dewhurst 31 Editor May 2012 Pam Reed 51 Bartender May 2012 Eleanor Hodgkins 72 Pensioner May 2012 Poppy Moore 73 Pensioner May 2012 Vincent Dogan 38 Unemployed and party activist May 2012 Bryan MacIntosh 41 Computer technician May 2012 Callum Everett 19 Unemployed May 2012 Danny Drysdale 21 Railworker May 2012 Emma Terrington 69 Pensioner May 2012 Fiona Harrison 23 Florist and business owner May 2012 George Carlisle 26 Mover May 2012 Harry Carlisle 24 Mover May 2012 Joe Fallon 19 McDonalds -

NSPIRE Approved Properties As of May 1, 2021

NSPIRE Approved Properties as of May 1, 2021 Title MFH Property ID PHA Code City State Parkwest Apartments 800000113 Fairbanks AK John L. Turner House 800217776 Fairbanks AK Elyton Village AL001000001 Birmingham AL Southtown Court AL001000004 Birmingham AL Smithfield Court AL001000009 Birmingham AL Harris Homes AL001000014 Birmingham AL Coooper Green Homes AL001000017 Birmingham AL Kimbrough Homes AL001000018 Birmingham AL Roosevelt City AL001000023 Birmingham AL Park Place I AL001000031 Birmingham AL Park Place II AL001000032 Birmingham AL Park Place III AL001000033 Birmingham AL Glenbrook at Oxmoor-Hope VI Phase I AL001000037 Birmingham AL Tuxedo Terrace I AL001000044 Birmingham AL Tuxedo Terrace II AL001000045 Birmingham AL Riverview AL005000001 Phenix City AL Douglas AL005000002 Phenix City AL Stough AL005000005 Phenix City AL Blake AL005000006 Phenix City AL Paterson Court AL006000004 Montgomery AL Gibbs Village West AL006000006 Montgomery AL Gibbs Village East AL006000007 Montgomery AL Colley Homes AL049000001 Gadsden AL Carver Village AL049000002 Gadsden AL Emma Sansom Homes AL049000003 Gadsden AL Gateway Village AL049000004 Gadsden AL Cambell court AL049000005 Gadsden AL Westfield Addition AL052000001 Cullman AL Hilltop AL052000004 Cullman AL Hamilton AL053000020 Hamilton AL Double Springs AL053000030 Hamilton AL John Sparkman Ct. AL089000001 Vincent AL Stalcup Circle AL090000001 Phil Campbell AL Stone Creek AL091001003 Arab AL Franconia Village AL098000001 Aliceville AL Marrow Village AL107000001 Elba AL Chatom Apts AL117000001 -

The Impact of Regeneration on Community Dynamics and Processes

Reconstructing Communities: the impact of regeneration on community dynamics and processes BY Stacy R. Pethia A thesis submitted to The University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Centre for Urban and Regional Studies Birmingham Business School College of Social Sciences The University of Birmingham January 2011 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. Abstract The New Labour government placed communities at the heart of urban regeneration policy. Area deprivation and social exclusion were to be addressed through rebuilding community in deprived areas, a process involving tenure diversification and the building of bridging social capital to support community empowerment, increased aspirations and wide-spread mutually supportive relationships. There is, however, little empirical evidence that tenure mix is an effective means for achieving the social goals of neighbourhood renewal. This thesis contributes to the mixed tenure debate by exploring the impact of regeneration on community. The research was guided by theories of social structure and cultural systems and argues that the regeneration process may give rise to social divisions and conflict between community groups, inhibiting culture change. -

Homes Fit for Heroes: the Rise and Fall of Council Housing

3 FEBRUARY 2020 Homes Fit for Heroes: The Rise and Fall of Council Housing PROFESSOR STEVE SCHIFFERES I would like to begin this talk with a paradox. Britain is the country that built more public housing than any major economy. By 1979 one in every three households lived in council housing. For half a century there was political consensus that government had to intervene in the housing market to ensure good housing for all and eliminate slums. The system where democratically elected local authorities built, owned and managed housing, while central government provided subsidies and set design rules, seemed set to endure. Yet within a few years the whole system of public housing was being dismantled. Since the 1980s, the majority of council housing has either been sold to existing tenants or transferred to non-profit housing associations (now known as registered social landlords). Councils were forbidden from building any new council housing, and the profits from the sales were transferred to the Treasury. This was the largest privatisation of all, raising more money than all the other sales of state-owned companies combined. Its popularity with working class voters, often voting Conservative for the first time, meant that it was almost impossible for other political parties to oppose it. Over time, however, the shift to reliance on the private sector to meet all housing need has proved problematic. Private house building never made up the slack caused by the cessation of all council house building, and house prices have now risen to levels that make housing unaffordable for many people.