The Identification of Chromosomal Translocation, T(4;6)(Q22;Q15), in Prostate Cancer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

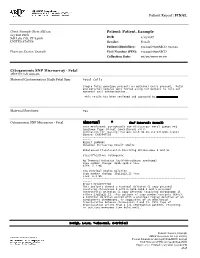

Cytogenomic SNP Microarray - Fetal ARUP Test Code 2002366 Maternal Contamination Study Fetal Spec Fetal Cells

Patient Report |FINAL Client: Example Client ABC123 Patient: Patient, Example 123 Test Drive Salt Lake City, UT 84108 DOB 2/13/1987 UNITED STATES Gender: Female Patient Identifiers: 01234567890ABCD, 012345 Physician: Doctor, Example Visit Number (FIN): 01234567890ABCD Collection Date: 00/00/0000 00:00 Cytogenomic SNP Microarray - Fetal ARUP test code 2002366 Maternal Contamination Study Fetal Spec Fetal Cells Single fetal genotype present; no maternal cells present. Fetal and maternal samples were tested using STR markers to rule out maternal cell contamination. This result has been reviewed and approved by Maternal Specimen Yes Cytogenomic SNP Microarray - Fetal Abnormal * (Ref Interval: Normal) Test Performed: Cytogenomic SNP Microarray- Fetal (ARRAY FE) Specimen Type: Direct (uncultured) villi Indication for Testing: Patient with 46,XX,t(4;13)(p16.3;q12) (Quest: EN935475D) ----------------------------------------------------------------- ----- RESULT SUMMARY Abnormal Microarray Result (Male) Unbalanced Translocation Involving Chromosomes 4 and 13 Classification: Pathogenic 4p Terminal Deletion (Wolf-Hirschhorn syndrome) Copy number change: 4p16.3p16.2 loss Size: 5.1 Mb 13q Proximal Region Deletion Copy number change: 13q11q12.12 loss Size: 6.1 Mb ----------------------------------------------------------------- ----- RESULT DESCRIPTION This analysis showed a terminal deletion (1 copy present) involving chromosome 4 within 4p16.3p16.2 and a proximal interstitial deletion (1 copy present) involving chromosome 13 within 13q11q12.12. This -

4P Duplications

4p Duplications rarechromo.org Sources 4p duplications The information A 4p duplication is a rare chromosome disorder in which in this leaflet some of the material in one of the body’s 46 chromosomes comes from the is duplicated. Like most other chromosome disorders, this medical is associated to a variable extent with birth defects, literature and developmental delay and learning difficulties. from Unique’s 38 Chromosomes come in different sizes, each with a short members with (p) and a long (q) arm. They are numbered from largest to 4p duplications, smallest according to their size, from number 1 to number 15 of them with 22, in addition to the sex chromosomes, X and Y. We a simple have two copies of each of the chromosomes (23 pairs), duplication of 4p one inherited from our father and one inherited from our that did not mother. People with a chromosome 4p duplication have a involve any other repeat of some of the material on the short arm of one of chromosome, their chromosomes 4. The other chromosome 4 is the who were usual size. 4p duplications are sometimes also called surveyed in Trisomy 4p. 2004/5. Unique is This leaflet explains some of the features that are the same extremely or similar between people with a duplication of 4p. grateful to the People with different breakpoints have different features, families who but those with a duplication that covers at least two thirds took part in the of the uppermost part of the short arm share certain core survey. features. References When chromosomes are examined, they are stained with a dye that gives a characteristic pattern of dark and light The text bands. -

ANALYSIS of CHROMOSOME 4 in DROSOPHZLA MELANOGASTER. 11: ETHYL METHANESULFONATE INDUCED Lethalsl’

ANALYSIS OF CHROMOSOME 4 IN DROSOPHZLA MELANOGASTER. 11: ETHYL METHANESULFONATE INDUCED LETHALSl’ BENJAMIN HOCHMAN Department of Zoology, The University of Tennessee, Knoxville, Tenn. 37916 Received October 30, 1970 OUTSIDE the realm of the prokaryotes, it may appear unlikely that a com- plete inventory of the genetic material contained in the individual vehicles of hereditary transmission, the chromosomes, can be obtained. The chromosomes of higher plants and animals are either too large or the methods required for such an analysis are lacking. However, an approach to the problem is possible with the smallest autosome (number 4) in Drosophila melanogaster. In this genetically best-known diploid organism appropriate methods are available and the size of chromosome 4 (0.2-0.3 p at oogonial metaphase) suggests that the number of loci might be a relatively small, workable figure. An attempt is being made to uncover all of the major loci on chromosome 4, i.e., those loci capable of mutating to either a recessive lethal, semilethal, sterile, or visible state. In the first paper of this series (HOCHMAN,GLOOR and GREEN 1964), we reported that a study of some 50 spontaneous and X-ray-induced lethals had revealed a minimum of 22 vital loci on the fourth chromosome. Subsequently, two brief communications (HOCHMAN1967a,b) noted that the use of chemical mutagens had substantially increased the number of lethal chro- mosomes recovered and raised the number of loci detected. This paper contains an account of approximately 100 chromosome 4 mutations induced by chemical means (primarily recessive lethals which occurred follow- ing treatments with ethyl methanesulfonate) . -

Multiple Regions of Chromosome 4 Demonstrating Allelic Losses in Breast Carcinomas1

[CANCER RESEARCH 59, 3576–3580, August 1, 1999] Advances in Brief Multiple Regions of Chromosome 4 Demonstrating Allelic Losses in Breast Carcinomas1 Narayan Shivapurkar, Sanjay Sood, Ignacio I. Wistuba, Arvind K. Virmani, Anirban Maitra, Sara Milchgrub, John D. Minna, and Adi F. Gazdar2 Hamon Center for Therapeutic Oncology Research [N. S., S. S., I. I. W., A. K. V., A. M., J. D. M., A. F. G.] and Departments of Pathology [A. K. V., A. M., S. M., A. F. G.], Internal Medicine [J. D. M.], and Pharmacology [J. D. M.], University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, Texas 75235 Abstract Previous allelotyping studies have documented allelic loss on one or both arms of chromosome 4 in several neoplasms including blad- Allelotyping studies suggest that allelic losses at one or both arms of der, cervical, colorectal, hepatocellular, and esophageal cancers and in chromosome 4 are frequent in several tumor types, but information about squamous cell carcinomas of head and neck and of the skin (6, breast cancer is scant. A recent comparative genomic hybridization anal- ysis revealed frequent losses of chromosome 4 in breast carcinomas. In an 15–20). Our recent studies demonstrated frequent losses at three effort to more precisely locate the putative tumor suppressor gene(s) on nonoverlapping sites located on both arms of chromosome 4 in MMs chromosome 4 involved in the pathogenesis of breast carcinomas, we and SCLCs (21). Phenotypic tumor suppression has been observed by performed loss of heterozygosity studies using 19 polymorphic microsat- the introduction of chromosome 4 into human glioma cells (22). Thus, ellite markers. -

Deletion Mapping of Chromosome 4 in Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma

Oncogene (1997) 14, 369 ± 373 1997 Stockton Press All rights reserved 0950 ± 9232/97 $12.00 Deletion mapping of chromosome 4 in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma Mark A Pershouse1,3, Adel K El-Naggar2, Kenneth Hurr2, Huai Lin1,3, WK Alfred Yung1,3 and Peter A Steck1,3 Departments of 1Neuro-Oncology and 2Pathology and 3The Brain Tumor Center, The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, Texas 77030, USA Genomic deletions involving chromosome 4 have recently Cytogenetic studies have identi®ed recurring, but been implicated in several human cancers. To identify widely varied alterations of chromosomes 1, 3, 4, 5, 7, and characterize genetic events associated with the 8, 9, 11, 14, 15 and 17 (Jin et al., 1993; Sreekantaiah et development of head and neck squamous cell carinoma al., 1994). Although several molecular studies have (HNSCC), a ®ne mapping of allelic losses associated shown that mutation of p53 and ampli®cation of with chromosome 4 was performed on DNA isolated epidermal growth factor receptor are relatively from 27 matched primary tumor specimens and normal common events. However, the exact genes that are tissues. Loss of heterozygosity (LOH) of at least one targeted in the majority of the observed chromosomal chromosome 4 polymorphic allele was seen in the alterations are unknown (Brachman et al., 1992; majority of tumors (92%). Allelic deletions were con®ned Grandis et al., 1993; Shin et al., 1994). Recently, to short arm loci in four tumors and to the long arm loci several groups have performed allelotyping studies on in 12 tumors, suggesting the presence of two regions of HNSCC specimens to further de®ne regions of common deletion. -

Variability of Human Rdna

cells Review Variability of Human rDNA Evgeny Smirnov *, Nikola Chmúrˇciaková , František Liška, Pavla Bažantová and Dušan Cmarko Institute of Biology and Medical Genetics, First Faculty of Medicine, Charles University and General University Hospital in Prague, 128 00 Prague, Czech Republic; [email protected] (N.C.); [email protected] (F.L.); [email protected] (P.B.); [email protected] (D.C.) * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: In human cells, ribosomal DNA (rDNA) is arranged in ten clusters of multiple tandem repeats. Each repeat is usually described as consisting of two parts: the 13 kb long ribosomal part, containing three genes coding for 18S, 5.8S and 28S RNAs of the ribosomal particles, and the 30 kb long intergenic spacer (IGS). However, this standard scheme is, amazingly, often altered as a result of the peculiar instability of the locus, so that the sequence of each repeat and the number of the repeats in each cluster are highly variable. In the present review, we discuss the causes and types of human rDNA instability, the methods of its detection, its distribution within the locus, the ways in which it is prevented or reversed, and its biological significance. The data of the literature suggest that the variability of the rDNA is not only a potential cause of pathology, but also an important, though still poorly understood, aspect of the normal cell physiology. Keywords: human rDNA; sequence variability; mutations; copy number 1. Introduction In human cells, ribosomal DNA (rDNA) is arranged in ten clusters of multiple tandem Citation: Smirnov, E.; repeats. -

Rare Allelic Forms of PRDM9 Associated with Childhood Leukemogenesis

Rare allelic forms of PRDM9 associated with childhood leukemogenesis Julie Hussin1,2, Daniel Sinnett2,3, Ferran Casals2, Youssef Idaghdour2, Vanessa Bruat2, Virginie Saillour2, Jasmine Healy2, Jean-Christophe Grenier2, Thibault de Malliard2, Stephan Busche4, Jean- François Spinella2, Mathieu Larivière2, Greg Gibson5, Anna Andersson6, Linda Holmfeldt6, Jing Ma6, Lei Wei6, Jinghui Zhang7, Gregor Andelfinger2,3, James R. Downing6, Charles G. Mullighan6, Philip Awadalla2,3* 1Departement of Biochemistry, Faculty of Medicine, University of Montreal, Canada 2Ste-Justine Hospital Research Centre, Montreal, Canada 3Department of Pediatrics, Faculty of Medicine, University of Montreal, Canada 4Department of Human Genetics, McGill University, Montreal, Canada 5Center for Integrative Genomics, School of Biology, Georgia Institute of Technology, Atlanta, Georgia, USA 6Department of Pathology, St. Jude Children's Research Hospital, Memphis, Tennessee, USA 7Department of Computational Biology and Bioinformatics, St. Jude Children's Research Hospital, Memphis, Tennessee, USA. *corresponding author : [email protected] SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION SUPPLEMENTARY METHODS 2 SUPPLEMENTARY RESULTS 5 SUPPLEMENTARY TABLES 11 Table S1. Coverage and SNPs statistics in the ALL quartet. 11 Table S2. Number of maternal and paternal recombination events per chromosome. 12 Table S3. PRDM9 alleles in the ALL quartet and 12 ALL trios based on read data and re-sequencing. 13 Table S4. PRDM9 alleles in an additional 10 ALL trios with B-ALL children based on read data. 15 Table S5. PRDM9 alleles in 76 French-Canadian individuals. 16 Table S6. B-ALL molecular subtypes for the 24 patients included in this study. 17 Table S7. PRDM9 alleles in 50 children from SJDALL cohort based on read data. 18 Table S8: Most frequent translocations and fusion genes in ALL. -

Machine Learning-Based Identification and Cellular Validation of Tropomyosin 1 As a Genetic Inhibitor of Hematopoiesis

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/631895; this version posted May 8, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. Machine learning-based identification and cellular validation of Tropomyosin 1 as a genetic inhibitor of hematopoiesis. Thom CS1,2,3*, Jobaliya CD4,5, Lorenz K2,3, Maguire JA4,5, Gagne A4,5, Gadue P4,5, French DL4,5, Voight BF2,3,6* 1Division of Neonatology, Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, Philadelphia, PA, USA 2Department of Systems Pharmacology and Translational Therapeutics, Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, USA 3Department of Genetics, Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, USA 4Center for Cellular and Molecular Therapeutics, The Children's Hospital of Philadelphia, PA, USA 5Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, The Children's Hospital of Philadelphia, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, USA 6Institute of Translational Medicine and Therapeutics, University of Pennsylvania, PA, USA *Corresponding authors: [email protected], [email protected] bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/631895; this version posted May 8, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. Introductory paragraph A better understanding of the genetic mechanisms regulating hematopoiesis are necessary, and could augment translational efforts to generate red blood cells (RBCs) and/or platelets in vitro. -

Disruption of ETV6 in Intron 2 Results in Upregulatory and Insertional Events in Childhood Acute Lymphoblastic Leukaemia

Leukemia (2008) 22, 114–123 & 2008 Nature Publishing Group All rights reserved 0887-6924/08 $30.00 www.nature.com/leu ORIGINAL ARTICLE Disruption of ETV6 in intron 2 results in upregulatory and insertional events in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukaemia GR Jalali1,2,QAn1, ZJ Konn, H Worley, SL Wright, CJ Harrison, JC Strefford1 and M Martineau1 Leukaemia Research Cytogenetics Group, Cancer Sciences Division, University of Southampton, Southampton, UK We describe four cases of childhood B-cell progenitor acute more often involved when the 12p rearrangements are balanced lymphoblastic leukaemia (BCP-ALL) and one of T-cell (T-ALL) rather than unbalanced, the latter often being associated with a with unexpected numbers of interphase signals for ETV6 with complex karyotype.10,11 The inherent instability of the ETV6 an ETV6–RUNX1 fusion probe. Three fusion negative cases each had a telomeric part of 12p terminating within intron 2 of gene has been demonstrated in several different studies by the ETV6, attached to sequences from 5q, 7p and 7q, respectively. use of cosmid probes to its individual exons. However, the series Two fusion positive cases, with partial insertions of ETV6 into of probes used have not always covered the complete gene, so chromosome 21, also had a breakpoint in intron 2. Fluores- the significance of some findings is unclear.3,6–8 Although ETV6 cence in situ hybridisation (FISH), array comparative genomic is an attractive candidate for the main target of the deletions and hybridization (aCGH) and Molecular Copy-Number Counting translocations associated with 12p, its central role remains (MCC) results were concordant for the T-cell case. -

Human Artificial Chromosomes Generated by Modification of a Yeast Artificial Chromosome Containing Both Human Alpha Satellite and Single-Copy DNA Sequences

Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA Vol. 96, pp. 592–597, January 1999 Genetics Human artificial chromosomes generated by modification of a yeast artificial chromosome containing both human alpha satellite and single-copy DNA sequences KARLA A. HENNING*, ELIZABETH A. NOVOTNY*, SHEILA T. COMPTON*, XIN-YUAN GUAN†,PU P. LIU*, AND MELISSA A. ASHLOCK*‡ *Genetics and Molecular Biology Branch and †Cancer Genetics Branch, National Human Genome Research Institute, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD 20892 Communicated by Francis S. Collins, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, November 6, 1998 (received for review September 3, 1998) ABSTRACT A human artificial chromosome (HAC) vec- satellite repeats also have been shown to be capable of human tor was constructed from a 1-Mb yeast artificial chromosome centromere function (13, 14). As for the third required ele- (YAC) that was selected based on its size from among several ment, the study of origins of DNA replication also has led to YACs identified by screening a randomly chosen subset of the conflicting reports, with no apparent consensus sequence Centre d’E´tude du Polymorphisme Humain (CEPH) (Paris) having yet been determined for the initiation of DNA synthesis YAC library with a degenerate alpha satellite probe. This in human cells (15, 16). YAC, which also included non-alpha satellite DNA, was mod- The production of HACs from cloned DNA sources should ified to contain human telomeric DNA and a putative origin help to define the elements necessary for human chromosomal of replication from the human b-globin locus. The resultant function and to provide an important vector suitable for the HAC vector was introduced into human cells by lipid- manipulation of large DNA sequences in human cells. -

Distinct Effects of Ionizing Radiation on in Vivo Murine Kidney and Brain Normal Tissue Gene Expression Weiling Zhao,1Eric Y

Cancer Therapy: Preclinical Distinct Effects of Ionizing Radiation on In vivo Murine Kidney and Brain Normal Tissue Gene Expression Weiling Zhao,1Eric Y. Chuang,2 Mark Mishra,3 Rania Awwad,3 Kheem Bisht,3 Lunching Sun,3 Phuongmai Nguyen,3 J. Daniel Pennington, 3 Tony Jau Cheng Wang,3 C. Matthew Bradbury, 3 Lei Huang,3 Zhijun Chen,3 Gil Bar-Sela,3 Michael E.C. Robbins,1and David Gius3 Abstract Purpose: There is a growing awareness that radiation-induced normal tissue injury in late- responding organs, such as the brain, kidney, and lung, involves complex and dynamic responses between multiple cell types that not only lead to targeted cell death but also acute and chronic alterations in cell function.The specific genes involved in the acute and chronic responses of these late-responding normal tissues remain ill defined; understanding these changes is critical to understanding the mechanism of organ damage. As such, the aim of the present study was to identify candidate genes involved in the development of radiation injury in the murine kidney and brain using microarray analysis. Experimental Design: A multimodality experimental approach combined with a comprehen- sive expression analysis was done to determine changes in normal murine tissue gene expression at 8 and 24 hours after irradiation. Results: A comparison of the gene expression patterns in normal mouse kidney and brain was strikingly different. This observation was surprising because it has been long assumed that the changes in irradiation-induced gene expression in normal tissues are preprogrammed genetic changes that are not affected by tissue-specific origin. -

ETV6/GOT1 Fusion in a Case of T(10;12)(Q24;P13)- Sis of Refractory Anemia with Excess Blasts (RAEB)

Letters to the Editor bone marrow showed 10% blasts establishing the diagno- ETV6/GOT1 fusion in a case of t(10;12)(q24;p13)- sis of refractory anemia with excess blasts (RAEB). Five positive myelodysplastic syndrome months later, she was admitted with a fever. A bone mar- row evaluation confirmed the transformation to an acute myeloid leukemia (AML) M1 according to the FAB classi- The ETV6/GOT1 fusion, resulting from t(10;12) fication. The patient died five days later. (q24;p13), has been recently described in a myelo- At diagnosis, karyotype revealed 46,XX,del(5)(q13q34) dysplastic syndrome. We reported a second case of [11]/46,idem,t(10;12)(q24;p13)[5]/46,XX[6]. The cytoge- t(10;12)-positive myelodysplastic syndrome in netic analysis at transformation displayed:46,XX,der whom fluorescent in situ hybridization confirmed (2)t(2;11)(q34;q14~21),del(5)(q13q34),idic(8)(p12),t(10;12) the non-random translocation but molecular biol- (q24;p13)[22]. ogy analyses revealed a ETV6/GOT1 chimera vary- As this case was very similar to the one previously ing from the first case described. described,6 we tested the hypothesis of a fusion involving ETV6 and GOT1 genes. Hybridization with the Citation: Struski S, Mauvieux L, Gervais C, Hélias C, Liu KL, and Lessard M. ETV6/GOT1 fusion in a case of t(10;12)(q24;p13)-positive myelodysplastic syndrome. Haematologica ETV6/AML1 probe (Abbott), which covers the SAM 2008 Mar; 93(3):467-468. doi: 10.3324/haematol.11988 domain of ETV6, and BAC RP11-441O15 (RZPD, Berlin, Germany) for the GOT1 locus, confirmed fusion signals of ETV6 (ets variant gene 6) is frequently rearranged in ETV6 and GOT1 on both derivative chromosomes 12 and both myeloid and lymphoid hematologic malignancies and 10 (Figure 1A).