Status of Bears in Bangladesh: Going, Going, Gone?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sloth Bear Zoo Experiences 3000

SLOTH BEAR ZOO EXPERIENCES 3000 Behind the Scenes With the Tigers for Four (BEHIND THE SCENES) Head behind the scenes for a face-to-face visit with Woodland Park Zoo’s new Malayan tigers. This intimate encounter will give you exclusive access to these incredible animals. Meet our expert keepers and find out what it’s like to care for this critically endangered species. You’ll learn about Woodland Park Zoo and Panthera’s work with on-the-ground partners in Malaysia to conserve tigers and the forests which these iconic big cats call home, and what you can do to help before it’s too late. Restrictions: Expires July 10, 2016. Please make mutually agreeable arrangements at least eight weeks in advance. Participants must be 12 years of age and older. THANK YOU: WOODLAND PARK ZOO EAST TEAM VALUE: $760 3001 Behind the Scenes Giraffe Feeding for Five (BEHIND THE SCENES) You and four guests are invited to meet the tallest family in town with this rare, behind-the-scenes encounter. Explore where Woodland Park Zoo’s giraffe spend their time off exhibit and ask our knowledgeable keepers everything you’ve ever wanted to know about giraffe and their care. You’ll even have the opportunity to help the keepers feed the giraffe a snack! This is a tall experience you won’t forget, and to make sure you don’t, we’ll send you home with giraffe plushes! Restrictions: Expires April 30, 2016. Please make mutually agreeable arrangements at least eight weeks in advance from 9:30 a.m.–2:00 p.m. -

Wildlife SOS SAVING INDIA’S WILDLIFE

Wildlife SOS SAVING INDIA’S WILDLIFE WILDLIFE SOS wildlifesos.org 1 www.wildlifesos.org WHO WE ARE Wildlife SOS was established in 1995 to protect India’s wildlife and wilderness from human exploitation. We are focused on threatened and endangered species like the Asian elephant and sloth bear, but also operate a leopard rescue center and run a 24-hour animal rescue service that provides aid to all creatures great and small — from injured turtles and birds to monkeys, tigers, and deer. Our mission involves three main branches: Welfare, Conservation, and Research. 1. WELFARE Wildlife SOS’s efforts to protect wildlife involve lifetime, high-quality care for animals who cannot return to the wild, medical treatment for animals that can, rescue services for captive animals in abusive settings, and advocacy to prevent animals from being exploited for entertainment. Wildlife SOS eradicated the cruel “dancing bear” practice in India, and we have been actively rescuing captive elephants from terrible situations (see below). Success Stories: Laxmi and Raj Bear Laxmi once begged on noisy and crowded city streets, morbidly obese from a diet of tourist junk food. Today, our good-natured girl is pampered at our sanctuary, feasting on a variety of healthier options, including her favorite: apples. Another success story: Raj, aka India’s last “dancing bear.” Back in 2009, we rescued and united Raj with hundreds of other bears we have saved from the cruel “dancing” trade. We still care for Raj as well more than 600 other bears. And we also provide training to their former owners to ensure that they can feed their families without ever exploiting an animal again. -

SRI LANKA Dec 24 – Jan 02, 2020

SRI LANKA Dec 24 – Jan 02, 2020 40 mammals, 213 birds, assorted reptiles and inverts! Tour operator: Bird and Wildlife Team (https://www.birdandwildlifeteam.com/) Species list key: SS = single sighting MS = multiple sightings SI = single individual MI = multiple individuals P0 = no photo opportunity P1 = poor photo opp P2 = average photo opp P3 = excellent photo opp Species Notes Lifer? Indian Hare MS/MI/P2 Mostly on night drives N Sri Lankan Giant Squirrel MI/MS/P1 Only 2 seen Y Three-striped Palm Squirrel MI/MS/P3 N Layard’s Palm Squirrel MI/MS/P2 Endemic Y Dusky Striped Squirrel MI/MS/P2 Endemic Y Asiatic Long-tailed Climbing Mouse MI/MS/P2 Night drives only Y Black Rat MI/SS/P1 Y Indian Gerbil MI/MS/P1 Night drives only Y Indian Crested Porcupine MI/MS/P1 Night hike Y Small Indian Civet SI/SS/P0 Night drive y Asian Palm Civet SI/SS/P1 Night drive N Jungle Cat SI/MS/P2 Daytime! Y Fishing Cat SI/SS/P0 Night drive Y Leopard MI/MS/P1 N Ruddy Mongoose MI/MS/P3 N Short-tailed Mongoose MI/MS/P3 Y Golden Jackal MI/MS/P1 Y Sloth Bear SI/SS/P0 N Asian House Shrew SI/SS/P0 Seen by LVN and DVN N/A Indian Flying Fox MI/MS/P3 N Greater Short-nosed Fruit Bat MI/MS/P0 Y Fulvous Fruit Bat MI/SS/P0 Y Dusky Roundleaf Bat MI/SS/P0 Y Schneider’s Leaf-nosed Bat MI/MS/P2 Y Lesser Large-footed Myotis MI/SS/P0 Y Kelaart’s Pipistrelle MI/SS/P0 Y Pygmy Pipistrelle MI/SS/P0 Y Red Slender Loris SI/SS/P0 Endemic Y Toque Macaque MS/MI/P3 Endemic Y Tufted Grey Langur MS/MI/P3 N Purple-faced Leaf-monkey MS/MI/P3 Endemic Y Sri Lankan (White-striped) Chevrotain MS/MI/P1 Endemic Y Eurasian Wild Boar MS/MI/P2 N Sambar MS/MI/P3 N Chital MS/MI/P3 N Indian Muntjac SS/SI/P0 N Wild Buffalo MS/MI/P3 But were they????? Y Feral Water Buffalo MS/MI/P3 Y Asian Elephant MS/MI/P3 N Blue Whale MS/MI/P2 N John Van Niel ([email protected]) My wife, adult daughter and I arranged a bird and mammal tour through the highly recommended Bird and Wildlife Team. -

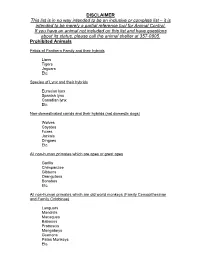

Prohibited and Regulated Animals List

DISCLAIMER This list is in no way intended to be an inclusive or complete list – it is intended to be merely a partial reference tool for Animal Control. If you have an animal not included on this list and have questions about its status, please call the animal shelter at 357-0805. Prohibited Animals Felids of Panthera Family and their hybrids Lions Tigers Jaguars Etc. Species of Lynx and their hybrids Eurasian lynx Spanish lynx Canadian lynx Etc. Non-domesticated canids and their hybrids (not domestic dogs) Wolves Coyotes Foxes Jackals Dingoes Etc. All non-human primates which are apes or great apes Gorilla Chimpanzee Gibbons Orangutans Bonobos Etc. All non-human primates which are old world monkeys (Family Cercopithecinae and Family Colobinae) Languars Mandrills Macaques Baboons Proboscis Mangabeys Guenons Patas Monkeys Etc. Prohibited Animals Continued: Other included animals Polar Bears Grizzly Bears Elephants Rhinoceroses Hippopotamuses Komodo Dragons Water Monitors Crocodile Monitors Members of the Crocodile Family African Rock Pythons Burmese Pythons Reticulated Pythons Anacondas All Venomous Reptiles – see attached list Venomous Reptiles Family Viperidae Family Elapidae mountain bush viper death adders Barbour’s short headed viper shieldnose cobras bush vipers collared adders jumping pit vipers water cobras Fea’s vipers Indian kraits adders and puff adders dwarf crowned snakes palm pit vipers Oriental coral snakes forest pit vipers venomous whip snakes lanceheads mambas Malayan pit vipers ornamental snakes Night adders Australian -

Spring 2018 Vol

International Bear News Tri-Annual Newsletter of the International Association for Bear Research and Management (IBA) and the IUCN/SSC Bear Specialist Group Spring 2018 Vol. 27 no. 1 Attendees of the 25th International Conference on Bear Research & Management in Quito, Ecuador. Read the conference summary on pages 18-29. IBA website: www.bearbiology.org Table of Contents INTERNATIONAL BEAR NEWS 3 International Bear News, ISSN #1064-1564 IBA PRESIDENT/IUCN BSG CO-CHAIRS 4 President’s Column 5 Is Conservation Advancing? It Depends How You Ask the Question IBA GRANTS PROGRAM NEWS CONFERENCE REPORT: 25th Conference on Bear 7 Bear Conservation Fund Report Research and Management 18 Session Summaries REFLECTIONS 27 Human-Bear Conflicts Workshop 7 Laurie Craig, Naturalist, US Forest Service 29 Student Activities CONFERENCE ANNOUNCEMENTS CONSERVATION 8 First Sight 30 26th International Conference on Bear Research & Management Illegal Trade 9 Understanding Use of Bear Parts in WORKSHOP ANNOUNCEMENTS Southeast Asia to Diminish Demand 2 24th Eastern Black Bear Workshop HUMAN BEAR CONFLICTS STUDENT FORUM 11 How Locals Characterize the Causes of 31 To Intern, or Not to Intern Sloth Bear Attacks in Jawai, Rajasthan 32 Truman Listserv and Facebook Page BIOLOGIcaL RESEARCH PUBLIcaTIONS 13 A Double-Edged Sword: American Black 33 Recent Bear Literature Bears Rely on Hunters’ Baits in the Face of Declining Natural Foods IBA OFFICERS & COUNCIL 15 Ecological Modeling of the Genus Ursus: 38 Executive Council Members and Ex-Officio What Does the Niche Tell Us? Members REVIEWS BSG EXPERT TEAM CHAIRS 16 Yellowstone Grizzly Bears - Ecology and 39 Bear Specialist Group Team Chairs Conservation of an Icon of Wildness 17 Press Release: Fifty Miles Outside Rome Live the Rarest Bears on Earth 2 International Bear News Spring 2018, vol. -

Home Ranges and Habitat Use of Sloth Bears Melursus Ursinus Inornatus in Wasgomuwa National Park, Sri Lanka Author(S): Shyamala Ratnayeke, Frank T

Home Ranges and Habitat Use of Sloth Bears Melursus Ursinus Inornatus in Wasgomuwa National Park, Sri Lanka Author(s): Shyamala Ratnayeke, Frank T. van Manen, U. K. G. K. Padmalal Source: Wildlife Biology, 13(3):272-284. Published By: Nordic Board for Wildlife Research DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.2981/0909-6396(2007)13[272:HRAHUO]2.0.CO;2 URL: http://www.bioone.org/doi/ full/10.2981/0909-6396%282007%2913%5B272%3AHRAHUO%5D2.0.CO%3B2 BioOne (www.bioone.org) is a nonprofit, online aggregation of core research in the biological, ecological, and environmental sciences. BioOne provides a sustainable online platform for over 170 journals and books published by nonprofit societies, associations, museums, institutions, and presses. Your use of this PDF, the BioOne Web site, and all posted and associated content indicates your acceptance of BioOne’s Terms of Use, available at www.bioone.org/page/terms_of_use. Usage of BioOne content is strictly limited to personal, educational, and non-commercial use. Commercial inquiries or rights and permissions requests should be directed to the individual publisher as copyright holder. BioOne sees sustainable scholarly publishing as an inherently collaborative enterprise connecting authors, nonprofit publishers, academic institutions, research libraries, and research funders in the common goal of maximizing access to critical research. Home ranges and habitat use of sloth bears Melursus ursinus inornatus in Wasgomuwa National Park, Sri Lanka Shyamala Ratnayeke, Frank T. van Manen & U.K.G.K. Padmalal Ratnayeke, S., van Manen, F.T. & Padmalal, U.K.G.K. 2007: Home ranges and habitat use of sloth bears Melursus ursinus inornatus in Was- gomuwa National Park, Sri Lanka. -

74 85 Lippenbaer ENGLISH.Indd

Bushy fur and mighty CLAWS Long shaggy hair—covering even the ears— is one of the features that distinguishes the Sloth bear from the other seven species of big bears. It uses its long claws to dig Across some of India’s up termite hills. remotest interiors wanders an animal that science knows little about: the Sloth bear. Axel Gomille (text and photos) travelled to the hills of Karnataka to study the family life of this secretive creature at close quarters. The unknown SLOTH BEAR 8/09 g 75 774_85_Lippenbaer4_85_Lippenbaer EENGLISH.inddNGLISH.indd 774-754-75 77/20/09/20/09 77:27:09:27:09 PPMM Once the cubs leave the shelter of the cave with their mother, they enjoy exploring the world around them— preferably riding piggyback. Soon they will feed on ants and termites, sucking out the insects with their highly mobile lips. SAFE on mother’s back 76 g 8/09 8/09 g 77 774_85_Lippenbaer4_85_Lippenbaer EENGLISH.inddNGLISH.indd 776-776-77 77/20/09/20/09 77:38:46:38:46 PPMM A peacock strutting by arouses the interest of the young ones. Their mother is never very far away and, at the first sign of danger, the cubs quickly return to the safety of her back— a pattern of behaviour not observed in any other species of bear. Here, in India, the mother’s back has proved to be a safe refuge against tigers and leopards. Curiosity overcomes FEAR 78 g 8/09 8/09 g 79 774_85_Lippenbaer4_85_Lippenbaer EENGLISH.inddNGLISH.indd 778-798-79 77/20/09/20/09 77:41:02:41:02 PPMM The presence of a male bear appears to threaten the safety of the cubs and so the mother charges at him with a mighty roar. -

Sloth Bear Attacks on Humans in Central India: Implications for Species Conservation

Human–Wildlife Interactions 12(3):338–347, Winter 2018 • digitalcommons.usu.edu/hwi Sloth bear attacks on humans in central India: implications for species conservation Nisha Singh, Wildlife & Conservation Biology Research Lab, HNG University, Patan, Gujarat, India -384265 [email protected] Swapnil Sonone, Youth for Nature Conservation Organization, Amravati, Maharashtra, India - 444606 Nishith Dharaiya, Wildlife & Conservation Biology Research Lab, HNG University, Patan Gujarat, India -384265 Abstract: Conflicts with wild animals are increasing as human populations grow and related anthropogenic activities encroach into wildlife habitats. A good example of this situation is the increase in conflicts between humans and sloth bears (Melursus ursinus) in India. Sloth bears are known for their aggressive and unpredictable behavior. More human fatalities and injuries have been attributed to sloth bear attacks than all recorded incidences of wildlife attacks in Buldhana Forest Division of Maharashtra, India. We interviewed 51 victims that were attacked by sloth bears between 2009-2017 to better understand the reasons for the attacks. Thirty- four of the attacks (66.7%) resulted in serious injuries, and there were 7 human mortalities (13.7%) reported. Most attacks occurred close to agricultural fields (66.7%) and during mid- day (1100–1400 hours). More attacks (64.7%) occurred when a person was working or resting in the field, or retrieving water for the field followed by attacks while watching over grazing livestock (13.7%). Individuals aged 31 to 40 years (35.3%) were the most common victims of sloth bear attacks. Half of the attacks were during monsoon season (July to October, 51%) followed by summer (March to June, 35%) and winter (November to February, 14%). -

Fishing Cat Prionailurus Viverrinus Bennett, 1833

Journal of Threatened Taxa | www.threatenedtaxa.org | 26 October 2018 | 10(11): xxxxx–xxxxx Fishing Cat Prionailurus viverrinus Bennett, 1833 (Carnivora: Felidae) distribution and habitat characteristics Communication in Chitwan National Park, Nepal ISSN 0974-7907 (Online) ISSN 0974-7893 (Print) Rama Mishra 1 , Khadga Basnet 2 , Rajan Amin 3 & Babu Ram Lamichhane 4 OPEN ACCESS 1,2 Central Department of Zoology, Tribhuvan University, Kirtipur, Kathmandu, Nepal 3 Conservation Programmes, Zoological Society of London, Regent’s Park, London, NW1 4RY, UK 4 National Trust for Nature Conservation - Biodiversity Conservation Center, Ratnanagar-6, Sauraha, Chitwan, Nepal 1 [email protected] (corresponding author), 2 [email protected], 3 [email protected], 4 [email protected] Abstract: The Fishing Cat is a highly specialized and threatened felid, and its status is poorly known in the Terai region of Nepal. Systematic camera-trap surveys, comprising 868 camera-trap days in four survey blocks of 40km2 in Rapti, Reu and Narayani river floodplains of Chitwan National Park, were used to determine the distribution and habitat characteristics of this species. A total of 19 photographs of five individual cats were recorded at three locations in six independent events. Eleven camera-trap records obtained during surveys in 2010, 2012 and 2013 were used to map the species distribution inside Chitwan National Park and its buffer zone. Habitat characteristics were described at six locations where cats were photographed. The majority of records were obtained in tall grassland surrounding oxbow lakes and riverbanks. Wetland shrinkage, prey (fish) depletion in natural wetlands and persecution threaten species persistence. Wetland restoration, reducing human pressure and increasing fish densities in the wetlands, provision of compensation for loss from Fishing Cats and awareness programs should be conducted to ensure their survival. -

Sloth Bear Melursus Ursinus

Sloth Bear Melursus ursinus Class: Mammalia Order: Carnivora Family: Ursidae Characteristics: Sloth bears are unique looking bears. These are mostly black bears with a V or Y whitish cream marking on the chest. The fur is long and shaggy. The long muzzle is also pale in color, mostly due to lack of fur in the area. Sloth bears have very long, flexible lips that are adapted for their diet of insects. They have very long claws for digging. Sloth bears are sometimes also called honey bears or lip bears. (Arkive) This species has the ability to close its nostrils so ant, termites, dirt, or bees do not get into the nose. These are medium size bears at about 5-6 feet long, 2-3 feet high at the shoulder, and weigh 120-310 pounds. (National Zoo) Behavior: Sloth bears are solitary creatures, living alone except during Range & Habitat: breeding season. They are generally nocturnal, especially when living in Most common in lowland forests an area near humans. These bears have been seen climbing high up trees of India and Sri Lanka. Some bears to knock down a honeycomb. (National Geographic) Sloth bears will stand in Nepal, and Bhutan on their hind legs and vocalize if threatened. They are not afraid to defend themselves against tigers, leopards, or humans. (Animal Diversity) These bears use their long claws to tear into termite mounds, then suck in to vacuum up all the insects within. (Arkive) Reproduction: Sloth bears only come together during breeding season. The female uses delayed implantation to decide the best time for her pregnancy and birthing. -

Report of the Presence of Wild Animals

Report of the Presence of Wild Animals The information recorded here is essential to emergency services personnel so that they may protect themselves and your neighbors, provide for the safety of your animals, ensure the maximum protection and preservation of your property, and provide you with emergency services without unnecessary delay. Every person in New York State, who owns, possesses, or harbors a wild animal, as set forth in General Municipal Law §209-cc, must file this Report annually, on or before April 1, of each year, with the clerk of the city, village or town (if outside a village) where the animal is kept. A list of the common names of animals to be reported is enclosed with this form. Failure to file as required will subject you to penalties under law. A separate Report is required to be filed annually for each address where a wild animal is harbored. Exemptions: Pet dealers, as defined in section 752-a of the General Business Law, zoological facilities and other exhibitors licensed pursuant to U.S. Code Title 7 Chapter 54 Sections 2132, 2133 and 2134, and licensed veterinarians in temporary possession of dangerous dogs, are not required to file this report. Instructions for completing this form: 1. Please print or type all information, using blue or black ink. 2. Fill in the information requested on this page. 3. On the continuation sheets, fill in the information requested for each type of animal that you possess. 4. Return the completed forms to the city, town, or village clerk of each municipality where the animal or animals are owned, possessed or harbored. -

Human–Sloth Bear Conflict in a Human-Dominated Landscape Of

Human–sloth bear conflict in a human-dominated landscape of northern Odisha, India Authors: Subrat Debata, Kedar Kumar Swain, Hemanta Kumar Sahu, and Himanshu Shekhar Palei Source: Ursus, 27(2) : 90-98 Published By: International Association for Bear Research and Management URL: https://doi.org/10.2192/URSUS-D-16-00007.1 BioOne Complete (complete.BioOne.org) is a full-text database of 200 subscribed and open-access titles in the biological, ecological, and environmental sciences published by nonprofit societies, associations, museums, institutions, and presses. Your use of this PDF, the BioOne Complete website, and all posted and associated content indicates your acceptance of BioOne’s Terms of Use, available at www.bioone.org/terms-of-use. Usage of BioOne Complete content is strictly limited to personal, educational, and non-commercial use. Commercial inquiries or rights and permissions requests should be directed to the individual publisher as copyright holder. BioOne sees sustainable scholarly publishing as an inherently collaborative enterprise connecting authors, nonprofit publishers, academic institutions, research libraries, and research funders in the common goal of maximizing access to critical research. Downloaded From: https://www.bioone.org/journals/Ursus on 1/2/2019 Terms of Use: https://www.bioone.org/terms-of-use Access provided by Norwegian University Library of Life Sciences Human–sloth bear conflict in a human-dominated landscape of northern Odisha, India Subrat Debata1 , Kedar Kumar Swain2 , Hemanta Kumar Sahu3 , and Himanshu Shekhar Palei3,4 1Department of Biodiversity and Conservation of Natural Resources, Central University of Orissa, Koraput-764020, Odisha, India 2Office of the Principal Chief Conservator of Forests (Wildlife) and Chief Wildlife Warden, Prakruti Bhawan, Nilakantha Nagar, Bhubaneswar - 751012, Odisha, India 3P.G.