Sloth Bear Attacks on Humans in Central India: Implications for Species Conservation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sloth Bear Zoo Experiences 3000

SLOTH BEAR ZOO EXPERIENCES 3000 Behind the Scenes With the Tigers for Four (BEHIND THE SCENES) Head behind the scenes for a face-to-face visit with Woodland Park Zoo’s new Malayan tigers. This intimate encounter will give you exclusive access to these incredible animals. Meet our expert keepers and find out what it’s like to care for this critically endangered species. You’ll learn about Woodland Park Zoo and Panthera’s work with on-the-ground partners in Malaysia to conserve tigers and the forests which these iconic big cats call home, and what you can do to help before it’s too late. Restrictions: Expires July 10, 2016. Please make mutually agreeable arrangements at least eight weeks in advance. Participants must be 12 years of age and older. THANK YOU: WOODLAND PARK ZOO EAST TEAM VALUE: $760 3001 Behind the Scenes Giraffe Feeding for Five (BEHIND THE SCENES) You and four guests are invited to meet the tallest family in town with this rare, behind-the-scenes encounter. Explore where Woodland Park Zoo’s giraffe spend their time off exhibit and ask our knowledgeable keepers everything you’ve ever wanted to know about giraffe and their care. You’ll even have the opportunity to help the keepers feed the giraffe a snack! This is a tall experience you won’t forget, and to make sure you don’t, we’ll send you home with giraffe plushes! Restrictions: Expires April 30, 2016. Please make mutually agreeable arrangements at least eight weeks in advance from 9:30 a.m.–2:00 p.m. -

Wildlife SOS SAVING INDIA’S WILDLIFE

Wildlife SOS SAVING INDIA’S WILDLIFE WILDLIFE SOS wildlifesos.org 1 www.wildlifesos.org WHO WE ARE Wildlife SOS was established in 1995 to protect India’s wildlife and wilderness from human exploitation. We are focused on threatened and endangered species like the Asian elephant and sloth bear, but also operate a leopard rescue center and run a 24-hour animal rescue service that provides aid to all creatures great and small — from injured turtles and birds to monkeys, tigers, and deer. Our mission involves three main branches: Welfare, Conservation, and Research. 1. WELFARE Wildlife SOS’s efforts to protect wildlife involve lifetime, high-quality care for animals who cannot return to the wild, medical treatment for animals that can, rescue services for captive animals in abusive settings, and advocacy to prevent animals from being exploited for entertainment. Wildlife SOS eradicated the cruel “dancing bear” practice in India, and we have been actively rescuing captive elephants from terrible situations (see below). Success Stories: Laxmi and Raj Bear Laxmi once begged on noisy and crowded city streets, morbidly obese from a diet of tourist junk food. Today, our good-natured girl is pampered at our sanctuary, feasting on a variety of healthier options, including her favorite: apples. Another success story: Raj, aka India’s last “dancing bear.” Back in 2009, we rescued and united Raj with hundreds of other bears we have saved from the cruel “dancing” trade. We still care for Raj as well more than 600 other bears. And we also provide training to their former owners to ensure that they can feed their families without ever exploiting an animal again. -

The Rhinolophus Affinis Bat ACE2 and Multiple Animal Orthologs Are Functional 2 Receptors for Bat Coronavirus Ratg13 and SARS-Cov-2 3

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.11.16.385849; this version posted November 17, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC 4.0 International license. 1 The Rhinolophus affinis bat ACE2 and multiple animal orthologs are functional 2 receptors for bat coronavirus RaTG13 and SARS-CoV-2 3 4 Pei Li1#, Ruixuan Guo1#, Yan Liu1#, Yintgtao Zhang2#, Jiaxin Hu1, Xiuyuan Ou1, Dan 5 Mi1, Ting Chen1, Zhixia Mu1, Yelin Han1, Zhewei Cui1, Leiliang Zhang3, Xinquan 6 Wang4, Zhiqiang Wu1*, Jianwei Wang1*, Qi Jin1*,, Zhaohui Qian1* 7 NHC Key Laboratory of Systems Biology of Pathogens, Institute of Pathogen 8 Biology, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Peking Union Medical College1, 9 Beijing, 100176, China; School of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Peking University2, 10 Beijing, China; .Institute of Basic Medicine3, Shandong First Medical University & 11 Shandong Academy of Medical Sciences, Jinan 250062, Shandong, China; The 12 Ministry of Education Key Laboratory of Protein Science, Beijing Advanced 13 Innovation Center for Structural Biology, Beijing Frontier Research Center for 14 Biological Structure, Collaborative Innovation Center for Biotherapy, School of Life 15 Sciences, Tsinghua University4, Beijing, China; 16 17 Keywords: SARS-CoV-2, bat coronavirus RaTG13, spike protein, Rhinolophus affinis 18 bat ACE2, host susceptibility, coronavirus entry 19 20 #These authors contributed equally to this work. 21 *To whom correspondence should be addressed: [email protected], 22 [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] 23 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.11.16.385849; this version posted November 17, 2020. -

First Record of Hose's Civet Diplogale Hosei from Indonesia

First record of Hose’s Civet Diplogale hosei from Indonesia, and records of other carnivores in the Schwaner Mountains, Central Kalimantan, Indonesia Hiromitsu SAMEJIMA1 and Gono SEMIADI2 Abstract One of the least-recorded carnivores in Borneo, Hose’s Civet Diplogale hosei , was filmed twice in a logging concession, the Katingan–Seruyan Block of Sari Bumi Kusuma Corporation, in the Schwaner Mountains, upper Seruyan River catchment, Central Kalimantan. This, the first record of this species in Indonesia, is about 500 km southwest of its previously known distribution (northern Borneo: Sarawak, Sabah and Brunei). Filmed at 325The m a.s.l., IUCN these Red List records of Threatened are below Species the previously known altitudinal range (450–1,800Prionailurus m). This preliminary planiceps survey forPardofelis medium badia and large and Otter mammals, Civet Cynogalerunning 100bennettii camera-traps in 10 plots for one (Bandedyear, identified Civet Hemigalus in this concession derbyanus 17 carnivores, Arctictis including, binturong on Neofelis diardi, three Endangered Pardofe species- lis(Flat-headed marmorata Cat and Sun Bear Helarctos malayanus, Bay Cat . ) and six Vulnerable species , Binturong , Sunda Clouded Leopard , Marbled Cat Keywords Cynogale bennettii, as well, Pardofelis as Hose’s badia Civet), Prionailurus planiceps Catatan: PertamaBorneo, camera-trapping, mengenai Musang Gunung Diplogale hosei di Indonesia, serta, sustainable karnivora forest management lainnya di daerah Pegunungan Schwaner, Kalimantan Tengah Abstrak Diplogale hosei Salah satu jenis karnivora yang jarang dijumpai di Borneo, Musang Gunung, , telah terekam dua kali di daerah- konsesi hutan Blok Katingan–Seruyan- PT. Sari Bumi Kusuma, Pegunungan Schwaner, di sekitar hulu Sungai Seruya, Kalimantan Tengah. Ini merupakan catatan pertama spesies tersebut terdapat di Indonesia, sekitar 500 km dari batas sebaran yang diketa hui saat ini (Sarawak, Sabah, Brunei). -

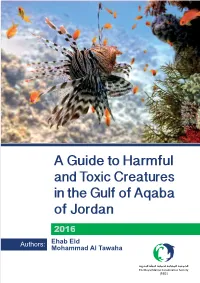

A Guide to Harmful and Toxic Creatures in the Goa of Jordan

Published by the Royal Marine Conservation Society of Jordan. P. O. Box 831051, Abdel Aziz El Thaalbi St., Shmesani 11183. Amman Copyright: © The Royal Marine Conservation Society of Jordan Reproduction of this publication for educational and other non- commercial purposes is authorized without prior written approval from the copyright holder provided the source is fully acknowledged. ISBN: 978-9957-8740-1-8 Deposit Number at the National Library: 2619/6/2016 Citation: Eid, E and Al Tawaha, M. (2016). A Guide to Harmful and Toxic Creature in the Gulf of Aqaba of Jordan. The Royal Marine Conservation Society of Jordan. ISBN: 978-9957-8740-1-8. Pp 84. Material was reviewed by Dr Nidal Al Oran, International Research Center for Water, Environment and Energy\ Al Balqa’ Applied University,and Dr. Omar Attum from Indiana University Southeast at the United State of America. Cover page: Vlad61; Shutterstock Library All photographs used in this publication remain the property of the original copyright holder, and it should not be reproduced or used in other contexts without permission. 1 Content Index of Creatures Described in this Guide ......................................................... 5 Preface ................................................................................................................ 6 Part One: Introduction ......................................................................................... 8 1.1 The Gulf of Aqaba; Jordan ......................................................................... 8 1.2 Aqaba; -

SRI LANKA Dec 24 – Jan 02, 2020

SRI LANKA Dec 24 – Jan 02, 2020 40 mammals, 213 birds, assorted reptiles and inverts! Tour operator: Bird and Wildlife Team (https://www.birdandwildlifeteam.com/) Species list key: SS = single sighting MS = multiple sightings SI = single individual MI = multiple individuals P0 = no photo opportunity P1 = poor photo opp P2 = average photo opp P3 = excellent photo opp Species Notes Lifer? Indian Hare MS/MI/P2 Mostly on night drives N Sri Lankan Giant Squirrel MI/MS/P1 Only 2 seen Y Three-striped Palm Squirrel MI/MS/P3 N Layard’s Palm Squirrel MI/MS/P2 Endemic Y Dusky Striped Squirrel MI/MS/P2 Endemic Y Asiatic Long-tailed Climbing Mouse MI/MS/P2 Night drives only Y Black Rat MI/SS/P1 Y Indian Gerbil MI/MS/P1 Night drives only Y Indian Crested Porcupine MI/MS/P1 Night hike Y Small Indian Civet SI/SS/P0 Night drive y Asian Palm Civet SI/SS/P1 Night drive N Jungle Cat SI/MS/P2 Daytime! Y Fishing Cat SI/SS/P0 Night drive Y Leopard MI/MS/P1 N Ruddy Mongoose MI/MS/P3 N Short-tailed Mongoose MI/MS/P3 Y Golden Jackal MI/MS/P1 Y Sloth Bear SI/SS/P0 N Asian House Shrew SI/SS/P0 Seen by LVN and DVN N/A Indian Flying Fox MI/MS/P3 N Greater Short-nosed Fruit Bat MI/MS/P0 Y Fulvous Fruit Bat MI/SS/P0 Y Dusky Roundleaf Bat MI/SS/P0 Y Schneider’s Leaf-nosed Bat MI/MS/P2 Y Lesser Large-footed Myotis MI/SS/P0 Y Kelaart’s Pipistrelle MI/SS/P0 Y Pygmy Pipistrelle MI/SS/P0 Y Red Slender Loris SI/SS/P0 Endemic Y Toque Macaque MS/MI/P3 Endemic Y Tufted Grey Langur MS/MI/P3 N Purple-faced Leaf-monkey MS/MI/P3 Endemic Y Sri Lankan (White-striped) Chevrotain MS/MI/P1 Endemic Y Eurasian Wild Boar MS/MI/P2 N Sambar MS/MI/P3 N Chital MS/MI/P3 N Indian Muntjac SS/SI/P0 N Wild Buffalo MS/MI/P3 But were they????? Y Feral Water Buffalo MS/MI/P3 Y Asian Elephant MS/MI/P3 N Blue Whale MS/MI/P2 N John Van Niel ([email protected]) My wife, adult daughter and I arranged a bird and mammal tour through the highly recommended Bird and Wildlife Team. -

Black Bear Attack Associations and Agency Risk Management

BLACK BEAR ATTACK ASSOCIATIONS AND AGENCY RISK MANAGEMENT By Janel Marie Scharhag A Thesis Submitted in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree MASTER OF SCIENCE IN NATURAL RESOURCES (WILDLIFE) College of Natural Resources UNIVERSITY OF WISCONSIN-STEVENS POINT Stevens Point, Wisconsin May 2019 APPROVED BY THE GRADUATE COMMITTEE OF: _____________________________________________________________ Dr. Cady Sartini, Graduate Advisor, Assistant Professor of Wildlife _____________________________________________________________ Dr. Shawn Crimmins, Assistant Professor of Wildlife _____________________________________________________________ Dr. Scott Hygnstrom, Professor of Wildlife ____________________________________________________________ Dr. Jeff Stetz, Research Coordinator, Region IV Alaska Fish and Game ii ABSTRACT Attacks by bears on humans have increased in the United States as both human and bear populations have risen. To mitigate the risk of future attacks, it is prudent to understand past attacks. Information and analyses are available regarding fatal attacks by both black (Ursus americanus) and brown bears (U. arctos), and non-fatal attacks by brown bears. No similar analyses on non-fatal black bear attacks are available. Our study addressed this information gap by analyzing all agency-confirmed, non-fatal attacks by black bears in the 48 conterminous United States from 2000-2017. Government agencies across the country are responsible for species conservation, population management, and conflict control. State, federal, and tribal agencies are required to make decisions that communicate and mitigate the risk of an attack to the public. Agencies have been held legally responsible for those decisions, consuming time and money in litigation. This had led to a call for a more refined way to assess the risk of a bear attack with the creation of a risk management model (RMM). -

Small Carnivores of Karnataka: Distribution and Sight Records1

Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society, 104 (2), May-Aug 2007 155-162 SMALL CARNIVORES OF KARNATAKA SMALL CARNIVORES OF KARNATAKA: DISTRIBUTION AND SIGHT RECORDS1 H.N. KUMARA2,3 AND MEWA SINGH2,4 1Accepted November 2006 2 Biopsychology Laboratory, University of Mysore, Mysore 570 006, Karnataka, India. 3Email: [email protected] 4Email: [email protected] During a study from November 2001 to July 2004 on ecology and status of wild mammals in Karnataka, we sighted 143 animals belonging to 11 species of small carnivores of about 17 species that are expected to occur in the state of Karnataka. The sighted species included Leopard Cat, Rustyspotted Cat, Jungle Cat, Small Indian Civet, Asian Palm Civet, Brown Palm Civet, Common Mongoose, Ruddy Mongoose, Stripe-necked Mongoose and unidentified species of Otters. Malabar Civet, Fishing Cat, Brown Mongoose, Nilgiri Marten, and Ratel were not sighted during this study. The Western Ghats alone account for thirteen species of small carnivores of which six are endemic. The sighting of Rustyspotted Cat is the first report from Karnataka. Habitat loss and hunting are the major threats for the small carnivore survival in nature. The Small Indian Civet is exploited for commercial purpose. Hunting technique varies from guns to specially devised traps, and hunting of all the small carnivore species is common in the State. Key words: Felidae, Viverridae, Herpestidae, Mustelidae, Karnataka, threats INTRODUCTION (Mukherjee 1989; Mudappa 2001; Rajamani et al. 2003; Mukherjee et al. 2004). Other than these studies, most of the Mammals of the families Felidae, Viverridae, information on these animals comes from anecdotes or sight Herpestidae, Mustelidae and Procyonidae are generally records, which no doubt, have significantly contributed in called small carnivores. -

Forest Degradation and Governance in Central India: Evidence from Ecology, Remote Sensing and Political Ecology

Forest Degradation and Governance in Central India: Evidence from Ecology, Remote Sensing and Political Ecology Meghna Agarwala Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy In the Graduate School of the Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2015 © 2014 Meghna Agarwala All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT Forest Degradation and Governance in Central India: Evidence from Ecology, Remote Sensing and Political Ecology Meghna Agarwala There is no clear consensus on the impact of local communities on the resources they manage, primarily due to a shortage of studies with large sample sizes that incorporate multiple causal factors. As governments decentralize resource management to local communities, it is important to identify factors that prevent resource degradation, to inform more effective decentralization, and help the development of institutional characteristics that prevent resource degradation. This study used remote sensing techniques to quantify forest biomass in tropical deciduous forests in Kanha-Pench landscape of Central India, and used these metrics to identify factors associated with changes in forest biomass. Kanha-Pench landscape was chosen because of its variation in forest use, and because forests were transferred over a period where satellite imagery was available to track changes. To verify that remote- sensing measured changes indeed constitute degradation, I conducted ecological studies in six villages, to understand changes in biomass, understory, canopy, species diversity and long-term forest composition in intensively used forests. To understand the impact of institutional variables on changes in forest, I interviewed members of forest management committees in fifty villages in the landscape, and tested which institutional variables were associated with changes in forest canopy since 2002, when the forests were decentralized to local communities. -

(Kopi Luwak) and Ethiopian Civet Coffee

Food Research International 37 (2004) 901–912 www.elsevier.com/locate/foodres Composition and properties of Indonesian palm civet coffee (Kopi Luwak) and Ethiopian civet coffee Massimo F. Marcone * Department of Food Science, Ontario Agricultural College, Guelph, Ont., Canada N1G 2W1 Received 19 May 2004; accepted 25 May 2004 Abstract This research paper reports on the findings of the first scientific investigation into the various physicochemical properties of the palm civet (Kopi Luwak coffee bean) from Indonesia and their comparison to the first African civet coffee beans collected in Ethiopia in eastern Africa. Examination of the palm civet (Kopi Luwak) and African civet coffee beans indicate that major physical differences exist between them especially with regards to their overall color. All civet coffee beans appear to possess a higher level of red color hue and being overall darker in color than their control counterparts. Scanning electron microscopy revealed that all civet coffee beans possessed surface micro-pitting (as viewed at 10,000Â magnification) caused by the action of gastric juices and digestive enzymes during digestion. Large deformation mechanical rheology testing revealed that civet coffee beans were in fact harder and more brittle in nature than their control counterparts indicating that gestive juices were entering into the beans and modifying the micro-structural properties of these beans. SDS–PAGE also supported this observation by revealing that proteolytic enzymes were penetrating into all the civet beans and causing substantial breakdown of storage proteins. Differences were noted in the types of subunits which were most susceptible to proteolysis between civet types and therefore lead to differences in maillard browning products and therefore flavor and aroma profiles. -

Prohibited and Regulated Animals List

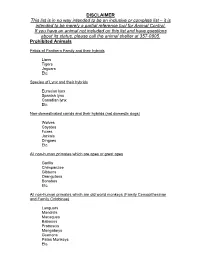

DISCLAIMER This list is in no way intended to be an inclusive or complete list – it is intended to be merely a partial reference tool for Animal Control. If you have an animal not included on this list and have questions about its status, please call the animal shelter at 357-0805. Prohibited Animals Felids of Panthera Family and their hybrids Lions Tigers Jaguars Etc. Species of Lynx and their hybrids Eurasian lynx Spanish lynx Canadian lynx Etc. Non-domesticated canids and their hybrids (not domestic dogs) Wolves Coyotes Foxes Jackals Dingoes Etc. All non-human primates which are apes or great apes Gorilla Chimpanzee Gibbons Orangutans Bonobos Etc. All non-human primates which are old world monkeys (Family Cercopithecinae and Family Colobinae) Languars Mandrills Macaques Baboons Proboscis Mangabeys Guenons Patas Monkeys Etc. Prohibited Animals Continued: Other included animals Polar Bears Grizzly Bears Elephants Rhinoceroses Hippopotamuses Komodo Dragons Water Monitors Crocodile Monitors Members of the Crocodile Family African Rock Pythons Burmese Pythons Reticulated Pythons Anacondas All Venomous Reptiles – see attached list Venomous Reptiles Family Viperidae Family Elapidae mountain bush viper death adders Barbour’s short headed viper shieldnose cobras bush vipers collared adders jumping pit vipers water cobras Fea’s vipers Indian kraits adders and puff adders dwarf crowned snakes palm pit vipers Oriental coral snakes forest pit vipers venomous whip snakes lanceheads mambas Malayan pit vipers ornamental snakes Night adders Australian -

Civettictis Civetta – African Civet

Civettictis civetta – African Civet continued to include it in Viverra. Although several subspecies have been recorded, their validity remains questionable (Rosevear 1974; Coetzee 1977; Meester et al. 1986). Assessment Rationale The African Civet is listed as Least Concern as it is fairly common within the assessment region, inhabits a variety of habitats and vegetation types, and is present in numerous protected areas (including Kruger National Park). Camera-trapping studies suggest that there are healthy populations in the mountainous parts of Alastair Kilpin Limpopo’s Waterberg, Soutpansberg, and Alldays areas, as well as the Greater Lydenburg area of Mpumalanga. However, the species may be undergoing some localised Regional Red List status (2016) Least Concern declines due to trophy hunting and accidental persecution National Red List status (2004) Least Concern (for example, poisoning that targets larger carnivores). Furthermore, the increased use of predator-proof fencing Reasons for change No change in the growing game farming industry in South Africa can Global Red List status (2015) Least Concern limit movement of African Civets. The expansion of informal settlements has also increased snaring incidents, TOPS listing (NEMBA) (2007) None since it seems that civets are highly prone to snares due CITES listing (1978) Appendix III to their regular use of footpaths. Elsewhere in Africa, this (Botswana) species is an important component in the bushmeat trade. Although the bushmeat trade is not as severe within the Endemic No assessment