Bob Campbell MW

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New Zealand Wine Fair Sa N Francisco 2013 New Zealand Wine Fair Sa N Francisco / May 16 2013

New Zealand Wine Fair SA N FRANCISCO 2013 New Zealand Wine Fair SA N FRANCISCO / MAY 16 2013 CONTENTS 2 New Zealand Wine Regions New Zealand Winegrowers is delighted to welcome you to 3 New Zealand Wine – A Land Like No Other the New Zealand Wine Fair: San Francisco 2013. 4 What Does ‘Sustainable’ Mean For New Zealand Wine? 5 Production & Export Overview The annual program of marketing and events is conducted 6 Key Varieties by New Zealand Winegrowers in New Zealand and export 7 Varietal & Regional Guide markets. PARTICIPATING WINERIES When you choose New Zealand wine, you can be confident 10 Allan Scott Family Winemakers you have selected a premium, quality product from a 11 Babich Wines beautiful, sophisticated, environmentally conscious land, 12 Coopers Creek Vineyard where the temperate maritime climate, regional diversity 13 Hunter’s Wines and innovative industry techniques encourage highly 14 Jules Taylor Wines distinctive wine styles, appropriate for any occasion. 15 Man O’ War Vineyards 16 Marisco Vineyards For further information on New Zealand wine and to find 17 Matahiwi Estate SEEKING DISTRIBUTION out about the latest developments in the New Zealand wine 18 Matua Valley Wines industry contact: 18 Mondillo Vineyards SEEKING DISTRIBUTION 19 Mt Beautiful Wines 20 Mt Difficulty Wines David Strada 20 Selaks Marketing Manager – USA 21 Mud House Wines Based in San Francisco 22 Nautilus Estate E: [email protected] 23 Pacific Prime Wines – USA (Carrick Wines, Forrest Wines, Lake Chalice Wines, Maimai Vineyards, Seifried Estate) Ranit Librach 24 Pernod Ricard New Zealand (Brancott Estate, Stoneleigh) Promotions Manager – USA 25 Rockburn Wines Based in New York 26 Runnymede Estate E: [email protected] 27 Sacred Hill Vineyards Ltd. -

Total Entries 2006 Competition

Page 1 TOTAL ENTRIES 2006 COMPETITION WINERY PARTICULAR NAME VINT MAIN GRAPE & % OTHERS & % STATE 3 BRIDGES CABERNET SAUVIGNON - WESTEND ESTATE 2002 CABERNET SAUVIGNON 90 PETIT VERDOT 10 A/NSW 3 BRIDGES CABERNET SAUVIGNON - WESTEND ESTATE SHOW RESERVE2003 CABERNET SAUVIGNON 90 PETIT VERDOT 10 A/NSW 3 BRIDGES CHARDONNAY - WESTEND ESTATE 2003 CHARDONNAY 100 A/NSW 3 BRIDGES DURIF- WESTEND ESTATE 2003 DURIF 100 A/NSW 3 BRIDGES RESERVE DURIF - WESTEND ESTATE 2003 DURIF 100 A/NSW 3 BRIDGES MERLOT - WESTEND ESTATE 2003 MERLOT 85 PETIT VERDOT 15 A/NSW 3 BRIDGES RESERVE BOTRYTIS - WESTEND ESTATE 2003 SEMILLON 60 PEDRO XIMENEZ 40 A/NSW 3 BRIDGES BOTRYTIS SEMILLON - WESTEND ESTATE GOLDEN MIST2003 SEMILLON 85 PEDRO XIMENEZ 15 A/NSW 3 BRIDGES BOTRYTIS SEMILLON - WESTEND ESTATE 2004 SEMILLON 85 PEDRO XIMENEZ 15 A/NSW 3 BRIDGES SHIRAZ - WESTEND ESTATE 2002 SHIRAZ 100 A/NSW 3 BRIDGES SHIRAZ - WESTEND ESTATE SHOW RESERVE 2003 SHIRAZ 100 A/NSW 3 BRIDGES SHIRAZ - WESTEND ESTATE LIMITED RELEASE RESERVE2003 SHIRAZ 100 A/NSW 3 BROTHERS WINERY GISBORNE CHARDONNAY 2004 CHARDONNAY 100 NZ 3 BROTHERS WINERY WAIRARAPA PINOT NOIR 2004 PINOT NOIR 90 MALBEC 10 NZ 3 BROTHERS WINERY MARLBOROUGH SAUVIGNON BLANC 2005 SAUVIGNON BLANC 100 NZ ABERCORN A RESERVE' VINTAGE PORT 2004 CABERNET 100 A/NSW ABERCORN A RESERVE' SHIRAZ 2003 SHIRAZ 100 A/NSW ABERCORN NJILLA 2004 SHIRAZ 100 A/NSW ABERCORN GROWERS REVENGE 2002 SHIRAZ 40 CABERNET SAUVIGNON 40A/NSW ADINFERN ESTATE SHIRAZ 2004 SHIRAZ 100 A/WA ALCIRA VINEYARD NUGAN ESTATE 2002 CABERNET SAUVIGNON 100 A/SA ALLAN SCOTT WINES -

New World Wine Awards 2015 Medal Results WINES ARE LISTED ALPHABETICALLY by MEDAL

New World Wine Awards 2015 Medal Results WINES ARE LISTED ALPHABETICALLY BY MEDAL Medal Wine Name & Vintage Medal Wine Name & Vintage Gold 36 bottles Chardonnay Central Otago 2013 Gold Taylors Eighty Acres Shiraz 2013 Gold 36 bottles Riesling Central Otago 2013 Gold Te Kairanga Pinot Noir 2013 Gold Abbey Cellars Medium Dry Riesling 2013 Gold Te Mata Estate Syrah Estate Vineyards 2013 Gold Anvers Razorback Road Shiraz Cabernet 2012 Gold The King's Bastard Chardonnay 2013 Gold Ara Single Estate Pinot Noir 2012 Gold The Ned Noble Sauvignon Blanc 2013 Gold Arrogant Frog Croak Baronne Syrah 2012 Gold The People's Sauvignon Blanc 2013 Gold Auntsfield Single Vineyard Sauvignon Blanc 2014 Gold The Sisters Sauvignon Blanc 2013 Gold Brancott Estate Living Land Chardonnay 2013 Gold Thistle Ridge Pinot Noir 2013 Gold Brancott Estate Sauvignon Gris 2014 Gold Tohu Marlborough Sauvignon Blanc 2014 Gold Brown Brothers Sparkling Moscato NV Gold Trinity Hill Hawkes Bay Merlot 2013 Gold Estampa Estate Syrah Cabernet Sauvignon 2011 Gold Trinity Hill Hawkes Bay Syrah 2013 Gold Forrest Pinot Gris 2013 Gold Two Rivers of Marlborough 'L'Ile de Beaute' Rosé 2014 Gold Framingham Classic Riesling 2012 Gold Vidal Hawkes Bay Chardonnay 2013 Gold Giesen Riesling 2013 Gold Vidal Reserve Hawkes Bay Chardonnay 2013 Gold Huntaway Reserve Pinot Noir 2013 Gold Villa Maria Cellar Selection Gold Kahurangi Estate Nelson Riesling 2011 Hawkes Bay Merlot Cabernet Sauvignon 2012 Gold Villa Maria Gold kate radburnd berry blush hawkes bay rosé 2014 Cellar Selection Marlborough Chardonnay -

1000 Best Wine Secrets Contains All the Information Novice and Experienced Wine Drinkers Need to Feel at Home Best in Any Restaurant, Home Or Vineyard

1000bestwine_fullcover 9/5/06 3:11 PM Page 1 1000 THE ESSENTIAL 1000 GUIDE FOR WINE LOVERS 10001000 Are you unsure about the appropriate way to taste wine at a restaurant? Or confused about which wine to order with best catfish? 1000 Best Wine Secrets contains all the information novice and experienced wine drinkers need to feel at home best in any restaurant, home or vineyard. wine An essential addition to any wine lover’s shelf! wine SECRETS INCLUDE: * Buying the perfect bottle of wine * Serving wine like a pro secrets * Wine tips from around the globe Become a Wine Connoisseur * Choosing the right bottle of wine for any occasion * Secrets to buying great wine secrets * Detecting faulty wine and sending it back * Insider secrets about * Understanding wine labels wines from around the world If you are tired of not know- * Serve and taste wine is a wine writer Carolyn Hammond ing the proper wine etiquette, like a pro and founder of the Wine Tribune. 1000 Best Wine Secrets is the She holds a diploma in Wine and * Pairing food and wine Spirits from the internationally rec- only book you will need to ognized Wine and Spirit Education become a wine connoisseur. Trust. As well as her expertise as a wine professional, Ms. Hammond is a seasoned journalist who has written for a number of major daily Cookbooks/ newspapers. She has contributed Bartending $12.95 U.S. UPC to Decanter, Decanter.com and $16.95 CAN Wine & Spirit International. hammond ISBN-13: 978-1-4022-0808-9 ISBN-10: 1-4022-0808-1 Carolyn EAN www.sourcebooks.com Hammond 1000WineFINAL_INT 8/24/06 2:21 PM Page i 1000 Best Wine Secrets 1000WineFINAL_INT 8/24/06 2:21 PM Page ii 1000WineFINAL_INT 8/24/06 2:21 PM Page iii 1000 Best Wine Secrets CAROLYN HAMMOND 1000WineFINAL_INT 8/24/06 2:21 PM Page iv Copyright © 2006 by Carolyn Hammond Cover and internal design © 2006 by Sourcebooks, Inc. -

2019 March, Review Sheet

Recent Reviews Dec/Jan 2019 100/100 from 100 Top By Bob Campbell MW New Release Wines Nov 28, 2018 HHHHH 99 Felton Road Wines Block 5 Pinot Noir 2017 2017 Felton Road Block 3 Pinot Noir, Central Otago, Bannockburn, Central Otago, NZD $109 A$135/NZ$109 This is an extraordinary wine. It boasts great purity and power with layer Extraordinarily complex. Layers of floral, herb, berry and savoury upon layer of subtle flavours that include violets, red rose petal, dark cherry characters are so multifaceted as to defy description. A seductively and mixed spices – a kaleidoscope of ever-changing characters most keenly silken texture adds to the appeal. I agonised over whether to give this displayed on the finish. It’s delicate, fragrant and has enormous length. wine 100 points; in hindsight I feel I may have been too conservative. Wonderful now – I look forward to charting its progress with bottle age. HHHHH Ageing: 2018-2027 97 2017 Felton Road Block Cornish Point Pinot Noir, FELTON ROAD Named in Central Otago, A$92/NZ$80 Wine Spectator’s Clearly a very successful vintage for Felton Road. Supple, elegant pinot noir with a sumptuous texture and floral, plum, dark cherry and Top 100 Wines of 2018 oriental spice flavours. The wine has an extraordinarily lengthy finish Wine Spectator, the world’s leading authority on wine, has – a sign of a real power. Accessible and appealing wine. announced Felton Road has been named the #12 wine in HHHHH this year’s list of the Top 100 Wines. The full list of the Top 100 Wines can be found online at 96 http://top100.winespectator.com. -

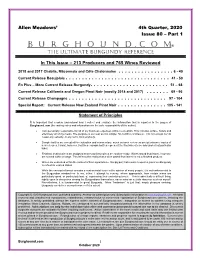

B U R G H O U N D . C O

Allen Meadows’ 4th Quarter, 2020 Issue 80 – Part 1 B U R G H O U N D . C O M® THE ULTIMATE BURGUNDY REFERENCE In This Issue – 213 Producers and 765 Wines Reviewed 2018 and 2017 Chablis, Mâconnais and Côte Chalonnaise . 6 - 40 Current Release Beaujolais . 41 - 50 En Plus – More Current Release Burgundy. 51 – 68 Current Release CaliFornia and Oregon Pinot Noir (mostly 2018 and 2017) . 69 - 96 Current Release Champagne . 97 - 104 Special Report: Current Release New Zealand Pinot Noir 105 - 141 . Statement of Principles It is important that readers understand how I collect and evaluate the information that is reported in the pages of Burghound.com (the tasting notes and information are the sole responsibility of the author). • I am personally responsible for all of my business expenses without exception. This includes airfare, hotels and effectively all of my meals. The purpose is as clear as it is simple: No conflicts of interest. I do not accept nor do I seek any subsidy, in any form, from anybody. • Sample bottles are accepted for evaluation and commentary, much as book reviewers accept advance copies of new releases. I insist, however, that these sample bottles represent the final wines to be sold under that particular label. • Finished, bottled wines are assigned scores as these wines are market-ready. Wines tasted from barrel, however, are scored within a range. This reflects the reality that a wine tasted from barrel is not a finished product. • Wines are evaluated within the context of their appellations. Simply put, that means I expect a grand cru Burgundy to reflect its exalted status. -

Addendum Regarding: the 2021 Certified Specialist of Wine Study Guide, As Published by the Society of Wine Educators

Addendum regarding: The 2021 Certified Specialist of Wine Study Guide, as published by the Society of Wine Educators This document outlines the substantive changes to the 2021 Study Guide as compared to the 2020 version of the CSW Study Guide. All page numbers reference the 2020 version. Note: Many of our regional wine maps have been updated. The new maps are available on SWE’s blog, Wine, Wit, and Wisdom, at the following address: http://winewitandwisdomswe.com/wine-spirits- maps/swe-wine-maps-2021/ Page 15: The third paragraph under the heading “TCA” has been updated to read as follows: TCA is highly persistent. If it saturates any part of a winery’s environment (barrels, cardboard boxes, or even the winery’s walls), it can even be transferred into wines that are sealed with screw caps or artificial corks. Thankfully, recent technological breakthroughs have shown promise, and some cork producers are predicting the eradication of cork taint in the next few years. In the meantime, while most industry experts agree that the incidence of cork taint has fallen in recent years, an exact figure has not been agreed upon. Current reports of cork taint vary widely, from a low of 1% to a high of 8% of the bottles produced each year. Page 16: the entry for Geranium fault was updated to read as follows: Geranium fault: An odor resembling crushed geranium leaves (which can be overwhelming); normally caused by the metabolism of sorbic acid (derived from potassium sorbate, a preservative) via lactic acid bacteria (as used for malolactic fermentation) Page 22: the entry under the heading “clone” was updated to read as follows: In commercial viticulture, virtually all grape varieties are reproduced via vegetative propagation. -

2020 Portfolio Summervolume 3

R&R Wine Marketing, Inc. Elegant Small Production Wines 2020 Portfolio SummerVolume 3 Also Proudly Representing: Specialty Cellars Vinthology Wines & CENTR CBD Brand www.rrwinemarketing.com 3585 Hancock Street Suite 100-A San Diego CA 92110 Phone: 619 221-8024 Fax: 619 221-8020 R&R WINE MARKETING PORTFOLIO Our Mission Statement We offer high quality, hand selected products while providing uncompromised personalized wine service. R&R shares our expert knowledge of wine and our passion for wine making, benefiting both on and off sale accounts. We service our accounts as friends and allies, providing them with the loyalty of a business partner. We are committed to standing apart and rising above others in the wine industry. Shipping Requirements Please contact your Sales Rep with orders by 2 pm for next day delivery. ,, *Minimum 2 case orders, or $300 per shipping company for free shipping. We are a proud partner with: ABX Delivery Service – San Diego Tues, Wed, Friday ABX Delivery Service - Orange County Tues- Friday ABX Delivery Service - Los Angeles Tues - Friday ABX Delivery Service – Palm Desert Thursday ONLY & Customs Wines Service- Delivery days are Tuesday Thru Friday For a fee to our client we offer: Golden State Overnight (GSO) for “wine-mergencies”: Monday – Saturday Orders must be in by noon for next day delivery. R&R WINE MARKETING INC. Our Sales Team Rob Rubin San Diego County 619-818-5444 [email protected] April Linn San Diego County 619-992-8661 [email protected] Cyndie McQueen San Diego County 619-933-7317 [email protected] Wendy Melford Los Angeles County 818-398-2110 [email protected] Johnny Walker Los Angeles County 714-232-2491 [email protected] Mark Abkin Specialty Cellars 858-223-5486 [email protected] R&R WINE MARKETING INC. -

The Buyer's New Zealand Wine Debate

The Buyer’s New Zealand Wine Debate In association with: The Buyer’s New Zealand Debate Setting The Scene Arguably New Zealand’s most successful exports over the last 10 years have been its rugby players and the growing reputation of its wine. Whilst the former have gone on to be World Champions in both 2011 and 2015, the country’s wines have enjoyed similar global success with export sales up 236% since 2006. A jump from 57.8 million litres in 2006 to 213m litres this year. The total tonnage of grapes crushed is also up 136% to 436,000 from 185,000 in 2006 (New Zealand Winegrowers). Such has been the popularity of New Zealand wine that anyone who invested in the sector over the last year 10 years would have seen their earnings double with an average yearly growth of 8.5%. But that does not necessarily mean all is fine and dandy in the land of the long white cloud. Whilst its wine sales have boomed in the UK over the last 10 years it has done so in two very distinct and different markets. On the one hand there is big box office New Zealand. The market buyers and consumers flock to every year for the latest mass volume, easy drinking, well-loved wines that fly off supermarket shelves and mainstream casual dining and pub wine lists. Then there are the more independent cinema, art house releases from New Zealand. These are rather less well known, and rely on a small, but loyal audience. It is arguably this second market which truly reflects the unique style and diversity of wines being made in New Zealand, in both its north and south islands. -

The Book of New Zealand Wine NZWG

NEW ZEALAND WINE Resource Booklet nzwine.com 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS 100% COMMITTED TO EXCELLENCE Tucked away in a remote corner of the globe is a place of glorious unspoiled landscapes, exotic flora and fauna, and SECTION 1: OVERVIEW 1 a culture renowned for its spirit of youthful innovation. History of Winemaking 1 New Zealand is a world of pure discovery, and nothing History of Winemaking Timeline 2 distills its essence more perfectly than a glass of New Zealand wine. Wine Production & Exports 3 New Zealand’s wine producing history extends back to Sustainability Policy 4 the founding of the nation in the 1800’s. But it was the New Zealand Wine Labelling Laws introduction to Marlborough’s astonishing Sauvignon & Export Certification 5 Blanc in the 1980’s that saw New Zealand wine receive Wine Closures 5 high acclaim and international recognition. And while Marlborough retains its status as one of the SECTION 2: REGIONS 6 world’s foremost wine producing regions, the quality of Wine Regions of New Zealand Map 7 wines from elsewhere in the country has also achieved Auckland & Northland 8 international acclaim. Waikato/ Bay of Plenty 10 Our commitment to quality has won New Zealand its reputation for premium wine. Gisborne 12 Hawke’s Bay 14 Wairarapa 16 We hope you find the materials of value to your personal and professional development. Nelson 18 Marlborough 20 Canterbury & Waipara Valley 22 Central Otago 24 RESOURCES AVAILABLE SECTION 3: WINES 26 NEW ZEALAND WINE RESOURCES Sauvignon Blanc 28 New Zealand Wine DVD Riesling 30 New Zealand Wine -

Some Wine Tasting and Food Pairing Suggestions

WORSHIPFUL COMPANY OF MANAGEMENT CONSULTANTS Virtual Wine Tasting – 12th June 2020 New Zealand Sauvignon Blanc background notes and suggestions for food pairing with thanks to Patrick McHugh and Ann Chapman © June 2020 WCoMC Wine Club Page 1 A bit of background No history of New Zealand Sauvignon Blanc wines is complete without understanding the importance of Marlborough and the role of Montana Wines. Montana Wines remains New Zealand’s largest wine producer and is the brand under which the UK was introduced to New Zealand wine during the 1980s. The winery has been so significant throughout New Zealand’s wine history that the Montana name is still used on domestic labelling due to its strong brand recognition. Ivan Yukich (Jukić), a Croatian immigrant planted his first vines in 1934, in Titirangi, situated in the Waitākere Ranges west of Auckland. The first wine was sold in 1944; by 1960 ten hectares (25 acres) of vineyards were planted. Ivan's sons, Mate and Frank, had become involved and they set up the company Montana Wines in 1961. By the end of the 1960s, the company had expanded further, planting vines on land south of Auckland. In 1973, the company expanded into Gisborne and Marlborough and exported its first wines in 1980. Montana was listed on the New Zealand Stock Exchange, initially as ‘Corporate Investments Limited’, and then as Montana Wines. Marlborough is located in the northeast of the South Island. The climate has a strong contrast between hot sunny days and cool nights, which extends the ripening period of the vines. This results in more intense flavour and aroma characters in the wine. -

Wine List Sugar Mill House Wines Carefully Chosen Popular Wines We Serve by Both the Glass and Bottle All Are $35 Per Bottle and $8 Per Glass

Wine List Sugar Mill House Wines Carefully chosen popular wines we serve by both the glass and bottle All are $35 per bottle and $8 per glass White Two Oceans Sauvingon Blanc 2014 - a fruity and tasty medium wine from South Africa. Just to drink by itself or good with fish and chicken. B7 Beringer Chardonnay 2013 – from the Napa Valley of California, a lighter bright Chardonnay with a hint of apple. By itself or blends well with chicken and coconut flavours. B8 Santa Margahrita - The best pino grigio at anything like this price – crisp and refreshing. B9 Muscadet De Sevre et Maine 2013 - from the north west Loire Valley of France . Made from the unique Melon grapes of the region. Dry and crisp and what the everyday French drink with seafood, risotto , crab and lobsters. B10 Red Broquel Pino Noir 2013 – from Argentina. The grapes grown at very high altitude give it a lighter, sharper yet rounded flavour. Very pleasant with duck and pork as well as red meats. B40 Excelsior – 2011 Syrah grapes grown on the De Wet Estate in South Africa's Robertson Valley make this wine the rich medium bodied drinking pleasure it is. And a perfect compliment to our lamb or duck. B41 Merlot – 2012 From Casa Lapostelle in Chile founded by the French Marnier family famous for its liqueur Grand Marnier. Rich full bodied and eminently potable. Great with our steaks. B42 Blackstone Merlot – special purchase of the deep red fruity California Merlot. Smooth and quaffable. While it lasts. Cabernet – 2013 From Beringer. They produce attractive drinkable wines at good prices and this cabernet is no exception.