Gabriel Orozco by Benjamin H

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Art in the Twenty-First Century Screening Guide: Season

art:21 ART IN2 THE TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY SCREENING GUIDE: SEASON TWO SEASON TWO GETTING STARTED ABOUT THIS SCREENING GUIDE ABOUT ART21, INC. This screening guide is designed to help you plan an event Art21, Inc. is a non-profit contemporary art organization serving using Season Two of Art in the Twenty-First Century. This guide students, teachers, and the general public. Art21’s mission is to includes a detailed episode synopsis, artist biographies, discussion increase knowledge of contemporary art, ignite discussion, and inspire questions, group activities, and links to additional resources online. creative thinking by using diverse media to present contemporary artists at work and in their own words. ABOUT ART21 SCREENING EVENTS Public screenings of the Art:21 series engage new audiences and Art21 introduces broad public audiences to a diverse range of deepen their appreciation and understanding of contemporary art contemporary visual artists working in the United States today and and ideas. Organizations and individuals are welcome to host their to the art they are producing now. By making contemporary art more own Art21 events year-round. Some sites plan their programs for accessible, Art21 affords people the opportunity to discover their broad public audiences, while others tailor their events for particular own innate abilities to understand contemporary art and to explore groups such as teachers, museum docents, youth groups, or scholars. possibilities for new viewpoints and self-expression. Art21 strongly encourages partners to incorporate interactive or participatory components into their screenings, such as question- The ongoing goals of Art21 are to enlarge the definitions and and-answer sessions, panel discussions, brown bag lunches, guest comprehension of contemporary art, to offer the public a speakers, or hands-on art-making activities. -

Death and the Invisible Hand: Contemporary Mexican Art, 1988-Present,” in Progress

DEATH AND THE INVISIBLE HAND: CONTEMPORARY MEXICAN ART, 1988-PRESENT by Mónica Rocío Salazar APPROVED BY SUPERVISORY COMMITTEE: ___________________________________________ Charles Hatfield, Co-Chair ___________________________________________ Charissa N. Terranova, Co-Chair ___________________________________________ Mark Rosen ___________________________________________ Shilyh Warren ___________________________________________ Roberto Tejada Copyright 2016 Mónica Salazar All Rights Reserved A mi papá. DEATH AND THE INVISIBLE HAND: CONTEMPORARY MEXICAN ART, 1988-PRESENT by MÓNICA ROCÍO SALAZAR, BS, MA DISSERTATION Presented to the Faculty of The University of Texas at Dallas in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN HUMANITIES – AESTHETIC STUDIES THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT DALLAS December 2016 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Research and writing of this dissertation was undertaken with the support of the Edith O’Donnell Institute of Art History. I thank Mrs. O’Donnell for her generosity and Dr. Richard Brettell for his kind support. I am especially grateful to Dr. Charles Hatfield and Dr. Charissa Terranova, co- chairs of this dissertation, for their guidance and encouragement. I thank Dr. Mark Rosen, Dr. Shilyh Warren, and Dr. Roberto Tejada for their time and commitment to this project. I also want to thank Dr. Adam Herring for his helpful advice. I am grateful for the advice and stimulating conversations with other UT Dallas professors—Dr. Luis Martín, Dr. Dianne Goode, Dr. Fernando Rodríguez Miaja—as well as enriching discussions with fellow PhD students—Lori Gerard, Debbie Dewitte, Elpida Vouitis, and Mindy MacVay—that benefited this project. I also thank Dr. Shilyh Warren and Dr. Beatriz Balanta for creating the Affective Theory Cluster, which introduced me to affect theory and helped me shape my argument in chapter 4. -

November Artists of the Western Hemisphere: Precursors of Modernism 1860- 1930 Dr

1967 ● September – November Artists of the Western Hemisphere: Precursors of Modernism 1860- 1930 Dr. Atl (Gerardo Murillo), Juan Manuel Blanes, Humberto Causa, Joaquín Clausell, Maurice Gallbraith Cullen, Stuart Davis, Thomas Eakins, Pedro Figari, Juan Francisco González, Childe Hassam, Saturnino Herrán, Winslow Homer, George Inness, Francisco Laso, Martín Malharro, John Marin, Vicente do Rego Monteiro, James Wilson Morrice, José Clemente Orozco, Amelia Peláez, Emilio Pettoruti, José Guadalupe Posada, Maurice Brazil Prendergast, Armando Reverón, Diego Rivera, Julio Ruelas, Albert P. Ryder , Andrés de Santa María, Eduardo Sivori , Joseph Stella, Tarsila do Amaral, Tom Thomson, Joaquín Torres-García, José María Velasco Elyseu d’Angelo Visconti Curator: Stanton Loomis Catlin ● December 1967 – January 1968 Five Latin American Artists at Work in New York Julio Alpuy , Carmen Herrera, Fernando Maza, Rudolfo Mishaan, Ricardo Yrarrázaval Curator: Stanton Loomis Catlin 1968 ● February – March Pissarro in Venezuela Fritz George Melbye, Camille Pissarro Curator: Alfredo Boulton ● March – May Beyond Geometry: An Extension of Visual-Artistic Language in Our Time Ary Brizzi, Oscar Bony, David Lamelas, Lía Maisonave, Eduardo Mac Entyre, Gabriel Messil, César Paternosto, Alejandro Puente , Rogelio Polesello, Eduardo Rodríguez, Carlos Silva, María Simón, Miguel Angel Vidal Curator: Jorge Romero Brest ● May – June Minucode 1 Marta Minujín ● September From Cézanne to Miró1 Balthus (Balthazar Klossowski de Rola), Max Beckmann, Umberto Boccioni, Pierre Bonnard, -

Compare Generic Viagra

FOUR SEASONS MAGAZINE BRIGHTBRIGHTGREAGREATT CITIESCITIES LIGHTSLIGHTS ATAT NIGHTNIGHT SHOP ISTANBUL MAKING THE CUT FASHION TAKES ON SAVILE ROW STYLE PULSE WHAT WORKS FOR FALL Move over, Miami. Mexico City, the very heart of Mexico and that other great gateway to all of Latin America, has become one of the art world’s most vibrant creative centres, with an ever-expanding art market and a solid base of superb museums, galleries, and year-round cultural attractions. Buoyed by the renaissance of architecturally rich dis- tricts like Condesa, an art deco jewel, and the bustling Centro Histórico, the city’s land- mark-filled downtown—proud symbols of local developers’, designers’, and artists’ entrepreneurial energy—the Mexican capital has launched an international art fair, too: México Arte Contemporáneo (MACO). As Mexico’s artistic, economic, and political nerve centre, Mexico City is a place of richly overlapping (some might say constantly colliding) cultures: ancient and modern; indigenous, European, and North American. For art- makers and art lovers alike, this potent mixture of energies and influences—of time rushing forward in la vida loca and history surging forth at every turn—has become the intriguing, irresistible essence of Mexico City’s 21st-century allure. Read on for an overview of Mexico City’s art scene. The time-pressed can focus on the short lists of artists and galleries. Mexican Art, ThenWith roots andin a figurative Now art Numerous artists in Mexico, tradition that stretched back aware of what their modernist to ancient Mesoamerican peers in Europe and North carvings, the great social- America were up to, chafed at realist muralists of the early government support of the 20th century—Diego Rivera, stylized mural painters. -

Arturo García Bustos Y Su Obra En La Caída Del Régimen Democrático En Guatemala

MEMORIA DEL V ENCUENTRO DE INVESTIGACIÓN Y DOCUMENTACIÓN DE ARTES VISUALES Director de arte Enrique Hernández Nava Coordinación editorial Virginia García Pérez Cuidado de la edición Amadís Ross, Carlos Martínez, Margarita González y Marta Hernández Diseño Yolanda Pérez Sandoval Formación José Luis Rojo Diseño de cubierta Yolanda Pérez Sandoval Inventar el futuro. Construcción política y acción cultural. Memoria del v Encuentro de Investigación y Documentación de Artes Visuales © Instituto Nacional de Bellas Artes y Literatura Primera edición: 2014 Reforma y Campo Marte s/n, Col. Chapultepec Polanco Del. Miguel Hidalgo, C. P. 11560, México, D. F. Todos los derechos reservados. Queda prohibida la reproducción parcial o total de esta obra por cualquier me- dio o procedimiento, comprendidos la reprografía o el tratamiento informático, la fotocopia o la grabación, sin la previa autorización por escrito del Instituto Nacional de Bellas Artes. Editor responsable: Instituto Nacional de Bellas Artes y Literatura. Reservas de Derechos al Uso Exclusivo No. 04-2010-052609561300-102, ISSN: En trámite. Impreso en México / Printed in Mexico ÍN DI CE PRESENTACIÓN 13 CONFERENCIA MAGISTRAL n Las matrices culturales andinas y mesoamericanas 17 de significar y simbolizar el futuro RICARDO MELGAR BAO CONSTRUCCIONES CRÍTICAS n ¿Es posible historiar lo inmediato? El Frente Gráfico 132, 49 paradojas de lucha CARLOS ARANDA MÁRQUEZ, EMERSON BALDERAS FERNÁNDEZ, EMILIA SOLÍS GONZÁLEZ n ¿Inventar el futuro o hacer realidad las utopías? 61 SILVIA FERNÁNDEZ H. n La teoría, compañeros, la teoría 73 ALBERTO HÍJAR SERRANO FUTUROS SOÑADOS n Blade Runner. El porvenir desencantado de Ridley Scott 83 MARÍA ELENA DURÁN PAYÁN n Apocalípticos y desintegrados. -

Featured Releases 2 Limited Editions 102 Journals 109

Lorenzo Vitturi, from Money Must Be Made, published by SPBH Editions. See page 125. Featured Releases 2 Limited Editions 102 Journals 109 CATALOG EDITOR Thomas Evans Fall Highlights 110 DESIGNER Photography 112 Martha Ormiston Art 134 IMAGE PRODUCTION Hayden Anderson Architecture 166 COPY WRITING Design 176 Janine DeFeo, Thomas Evans, Megan Ashley DiNoia PRINTING Sonic Media Solutions, Inc. Specialty Books 180 Art 182 FRONT COVER IMAGE Group Exhibitions 196 Fritz Lang, Woman in the Moon (film still), 1929. From The Moon, Photography 200 published by Louisiana Museum of Modern Art. See Page 5. BACK COVER IMAGE From Voyagers, published by The Ice Plant. See page 26. Backlist Highlights 206 Index 215 Hilma af Klint: Paintings for the Future Edited with text by Tracey Bashkoff. Text by Tessel M. Bauduin, Daniel Birnbaum, Briony Fer, Vivien Greene, David Max Horowitz, Andrea Kollnitz, Helen Molesworth, Julia Voss. When Swedish artist Hilma af Klint died in 1944 at the age of 81, she left behind more than 1,000 paintings and works on paper that she had kept largely private during her lifetime. Believing the world was not yet ready for her art, she stipulated that it should remain unseen for another 20 years. But only in recent decades has the public had a chance to reckon with af Klint’s radically abstract painting practice—one which predates the work of Vasily Kandinsky and other artists widely considered trailblazers of modernist abstraction. Her boldly colorful works, many of them large-scale, reflect an ambitious, spiritually informed attempt to chart an invisible, totalizing world order through a synthesis of natural and geometric forms, textual elements and esoteric symbolism. -

PRUEBA 13.Indd

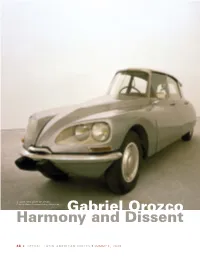

5 La DS, 1993. Citroën DS alterado. Cortesía Marian Goodman Gallery, Nueva York. Gabriel Orozco Harmony and Dissent 48 4 LITERAL. LATIN AMERICAN VOICES • SUMMER, 2008 5 Dark Wave, 2006. Vista de la instalacion en White Cube, Londres, UK. Photo: Stephen White. Cortesía del artista y Kurimanzutto, México. GALLERY The Poetry 3 By Evan J. Garza A master of diverse media and subject mat- of ters, Orozco has created a substantial body Forms of work that, at each stage of his career, leaves absolutely no detail with which to predict his impending projects. I MAGES COURTESY OF KURIMANZUTTO GAL- LERY, MEXICO. VERANO, 2008 • LITERAL. VOCES LATINOAMERICANAS 3 49 5 Grafi to sobre esqueleto de ballena gris, 2006. Vista de la instalación en la Biblioteca José Vasconcelos, México. Foto: Michel Zabé y Enrique Macías Cortesía del artista y Kurimanzutto, México. The phrase, “beauty is in the eye of the beholder”, sug- star Gabriel Kuri, who was active in Orozco’s studio for a gests that discovering splendor is an altogether subjec- large part of the late 80s and early 90s. Kuri’s attention tive experience. And if that’s the case, it’s not the thing to post-minimalism, conceptualism, and found objects that is beautiful, but instead the relationship to the were undoubtedly infl uenced during this period. While object is what remains gorgeous. This theory resounds Kuri’s work is more focused on man’s relationship to ma- through much of Mexican artist Gabriel Orozco’s work, terialism, the fundamental roots of this investigation lie in in each of his many mediums—as if dangling the fantas- the study of objects, a key element of Orozco’s work. -

Gabriel Orozco: New Photographs

M A R I A N G O O D M A N G A L L E R Y For Immediate Release. Gabriel Orozco: New Photographs November 14, 2002 - January 4, 2003 Opening reception: Thursday, November 14, 2002 Marian Goodman Gallery is delighted to announce the occasion of a special exhibition of new photographs by Gabriel Orozco. The exhibition will open on Thursday, November 14th and will be on view in the South Gallery through Saturday, January 4, 2003. In this new series of photographs taken in July on a trip to Mali, Orozco continues his concerns with sculpture and landscape, presenting the unexpected but mesmerizing side of the everyday. The works concentrate on objects, phenomena, erosion, materiality, and the organic. A well, a field, a stone path, a town, a mosque, a cemetery in legendary Timbuktu, the mysterious city on the trans- Saharan caravan route – spaces with a complex history but presented directly, with their surprising and contemporary aspect revealed. For over a decade Orozco’s work has addressed the possibilities inherent in the nexus of sculpture and photography. In his work, the ambiguity that exists between object and image is full of potential: the photograph can result from contingencies of the environment, from transient encounters between the artist and the materials of every day life, or from a series of sculptural strategies. Orozco’s photographs are vehicles of transport for the ephemeral—constituent of transit, movement, time, and space. In this exhibition, the choice of an enlarged format permits an attention to matter and scale and allows a focussed perception and a sense of wholeness in the artist’s working method. -

Gabriel Orozco 1962 Born in Veracruz, Mexico 1986-87 Circulo De Bellas

Gabriel Orozco 1962 Born in Veracruz, Mexico 1986-87 Circulo de Bellas Artes, Madrid, Spain 1981-84 Ecole Nationale des Arts Plastiques, U.N.A.M., Mexico, Mexico Residencies 2014-2015 Domaine de Chaumont-sur-Loire. Artist Residency. Loire, France 1995 Deutscher Akademischer Austausch Dienst DA. Artist Residency. Berlin, Germany Select Solo Exhibitions 2020 Gabriel Orozco, Marian Goodman Gallery, New York, NY 2019 Rotating Objects. The Noguchi Museum, New York. Gabriel Orozco: veladoras arte universal. Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes Cuba, La Habana. Gabriel Orozco. Rat Hole Gallery, Tokio. 2018 Gabriel Orozco, Marian Goodman Gallery, New York 2017 Gabriel Orozco, Chantal Crousel Gallery, Paris Gabriel Orozco, Kurimanzutto, Mexico City, Mexico 2016 Gabriel Orozco, White Cube, Hong Kong Gabriel Orozco, Aspen Art Museum, Colorado Orozco Garden, South London Gallery, London 2015 Visible Labor. Rat Hole Gallery, Tokyo. Gabriel Orozco. Marian Goodman Gallery, London. Inner Cycles. Museum of Contemporary Art Tokyo. Fleurs fantômes. Chaumont-sur-Loire, France. 2014 Natural Motion. Moderna Museet, Stockholm. Gabriel Orozco. Marian Goodman Gallery, New York. 2013 Natural Motion. Kunstahaus Bregenz, Austria. Chicotes. Faurschou Foundation Beijing. Spanish Lessons. Marian Goodman Gallery, New York. Thinking in Circles. Fruitmarket Gallery, Edinburgh. Gabriel Orozco. kurimanzutto, Mexico City. 2012 Asterisms. Deutsche-Guggenheim, Berlin; Guggenheim New York. Gabriel Orozco. Galerie Chantal Crousel, Paris. Gabriel Orozco. Galerie Marian Goodman, Paris. 2011 Gabriel Orozco. Tate Modern, London. Gabriel Orozco. Galerie Chantal Crousel, Paris. 2010 Gabriel Orozco. Kunstmuseum Basel, Switzerland; Musée National d’Art Moderne, Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris. 2009 Gabriel Orozco. Middlesbrough Institute of Modern Art, Middlesbrough, United Kingdom. Gabriel Orozco. Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), New York. -

Neevia Docconverter

Capítulo 1 Caminos de las artes visuales en México La práctica de las artes visuales en México en los últimos años del siglo XX y los primeros del siglo XXI es fuente de una amplia variedad de nombres, posturas intelectuales y artísticas, recursos materiales, y formas de expresión. Apelar a la obra de los creadores que gozan de un reconocimiento internacional resulta insuficiente en la aproximación a la producción plástica mexicana más reciente: Diego Rivera, José Clemente Orozco, David Alfaro Siqueiros, Frida Kahlo, Rufino Tamayo, José Luis Cuevas, Enrique Carbajal Sebastián , Francisco Toledo, Gabriel Orozco, constituyen referencias en las que se asienta una parte del registro de la vida cultural del país en su tránsito a lo largo del siglo, mas el carácter de figuras ‘emblemáticas’ del que gozan, distrae la atención de los diversos eventos, ya sociales, políticos, artísticos, o culturales, que han interactuado en el camino de las artes visuales mexicanas. A la par de la presencia, de dimensiones monumentales, de la obra mural de la Escuela Mexicana de Pintura (representada, de primera mano, por Rivera, Orozco y Siqueiros, y continuada por la labor, no menos importante, de José Chávez Morado, Francisco Eppens); de la insistencia en la figura de Kahlo como referencia preponderante del arte mexicano realizado por mujeres; de la Neevia docConverter 5.1 2 amalgama estilística entre lo ‘nacional’ y lo ‘internacional’ atribuida a Tamayo; del carácter ‘internacional’ y ‘polémico’ con que frecuentemente se identifica a Cuevas; de la puesta en boga de la escultura pública monumental a manos de Sebastián; del carácter ‘mágico’ con que se encasilla la labor de Toledo; y de la ‘prueba’ de la inserción de México en el panorama artístico internacional con la labor de Gabriel Orozco, coexiste un conjunto amplio de obras y actividades que, en algunos casos, han gozado de apoyo institucional público y/o privado, y en otros, se han desarrollado en círculos reducidos. -

“Pago En Especie”. Colección Del Museo De Arte De La Secretaría De Hacienda Y Crédito Público, Un Estudio De Caso

COLEGIO DE HUMANIDADES Y CIENCIAS SOCIALES LICENCIATURA EN ARTE Y PATRIMONIO CULTURAL Gestión y control de colecciones patrimoniales: “Pago en especie”. Colección del Museo de Arte de la Secretaría de Hacienda y Crédito Público, un estudio de caso. TRABAJO RECEPCIONAL PARA OBTENER EL GRADO DE LICENCIADA EN ARTE Y PATRIMONIO CULTURAL P R E S E N T A: Maribel Cabrera García Directora del trabajo recepcional Doctora Ana Bertha de Jesús Hernández Villarreal Ciudad de México, marzo 2016. SISTEMA BIBLIOTECARIO DE INFORMACIÓN Y DOCUMENTACIÓN UNIVERSIDAD AUTÓNOMA DE LA CIUDAD DE MÉXICO COORDINACIÓN ACADÉMICA RESTRICCIONES DE USO PARA LAS TESIS DIGITALES DERECHOS RESERVADOS© La presente obra y cada uno de sus elementos está protegido por la Ley Federal del Derecho de Autor; por la Ley de la Universidad Autónoma de la Ciudad de México, así como lo dispuesto por el Estatuto General Orgánico de la Universidad Autónoma de la Ciudad de México; del mismo modo por lo establecido en el Acuerdo por el cual se aprueba la Norma mediante la que se Modifican, Adicionan y Derogan Diversas Disposiciones del Estatuto Orgánico de la Universidad de la Ciudad de México, aprobado por el Consejo de Gobierno el 29 de enero de 2002, con el objeto de definir las atribuciones de las diferentes unidades que forman la estructura de la Universidad Autónoma de la Ciudad de México como organismo público autónomo y lo establecido en el Reglamento de Titulación de la Universidad Autónoma de la Ciudad de México. Por lo que el uso de su contenido, así como cada una de las partes que lo integran y que están bajo la tutela de la Ley Federal de Derecho de Autor, obliga a quien haga uso de la presente obra a considerar que solo lo realizará si es para fines educativos, académicos, de investigación o informativos y se compromete a citar esta fuente, así como a su autor ó autores. -

Landings Okwui Enwezor in Conversation With

LANDINGS OKWUI ENWEZOR Massimiliano Gioni When did you frst see Nari’s work? Okwui Enwezor I can’t remember exactly when I met Nari, but I believe it was in the late 1980s. He was IN CONVERSATION WITH still a student at Hunter College, before going to do his MFA at Brooklyn College. It must have been around 1989 or ’90 when we frst met. He wasn’t a sculptor then. MASSIMILIANO GIONI He was a painter, but his repertoire soon expanded and he became an artist not burdened by any specifc medium. We were connected through many other people and friends. We must have met through a photographer by the name of Gregory Christopher, who at the time worked as an assistant to the legendary photographer Roy DeCarava, and Iké Udé, who was an old friend from our boarding school days in Nigeria. I wasn’t an artist or an art critic or a curator. I was a writer, or an aspiring writer, and a poet, you could say, doing the rounds of poetry readings, art galleries, and museums. We haunted SoHo galleries and Lower East Side dives. We were intensely writing, reading, looking, and—in the jargon of the era—interrogating rela- tions of power and domination. Those were halcyon days, but important ones for my formation thirty years ago. MG What were your shared interests? OE For me, it was a very meaningful context to be in; it allowed me to be in touch with a group of engaged black practitioners in their twenties with a certain commitment to the production of ideas and to challenging the exclusionary context of the artis- tic milieu in New York—that is to say, white power structures.