Sex Education in the Age of Vlogging

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Identity and Representation on the Neoliberal Platform of Youtube

Identity and Representation on the Neoliberal Platform of YouTube Andra Teodora Pacuraru Student Number: 11693436 30/08/2018 Supervisor: Alberto Cossu Second Reader: Bernhard Rieder MA New Media and Digital Culture University of Amsterdam Table of Contents Introduction ............................................................................................................................................ 2 Chapter 1: Theoretical Framework ........................................................................................................ 4 Neoliberalism & Personal Branding ............................................................................................ 4 Mass Self-Communication & Identity ......................................................................................... 8 YouTube & Micro-Celebrities .................................................................................................... 10 Chapter 2: Case Studies ........................................................................................................................ 21 Methodology ............................................................................................................................. 21 Who They Are ........................................................................................................................... 21 Video Evolution ......................................................................................................................... 22 Audience Statistics ................................................................................................................... -

Snowschool Offered to Local Students Environment

6 TUESDAY, JANUARY 28, 2020 The Inyo Register SnowSchool offered to local students environment. The second with water. The food color- journey is unique. This Bishop, session allows students to ing and glitter represent game shows students how Mammoth review the first lesson and different, pollutants that water moves through the learn how to calculate snow might enter the watershed, earth, oceans, and atmo- Lakes fifth- water equivalent. The final and students can observe sphere, and gives them a grade students session takes students how the pollutants move better understanding of from the classroom to the and collect in different the water cycle. participate in mountains for a SnowSchool bodies of water. For the final in-class field day. Once firmly in For the second in-class activity, students learn SnowSchool snowshoes, the students activity, students focus on about winter ecology and learn about snow science the water cycle by taking how animals adapt for the By John Kelly hands-on and get a chance on the role of a water mol- winter. Using Play-Doh, Education Manager, ESIA to play in the snow. ecule and experiencing its they create fictional ani- During the in-class ses- journey firsthand. Students mals that have their own For the last five years, sion, students participate break up into different sta- winter adaptations. Some the Eastern Sierra in three activities relating tions. Each station repre- creations in past Interpretive Association to watersheds, the water sents a destination a water SnowSchools had skis for (ESIA) and Friends of the cycle, and winter ecology. molecule might end up, feet to move more easily Inyo have provided instruc- In the first activity, stu- such as a lake, river, cloud, on the snow and shovels tors who deliver the Winter dents create their own glacier, ocean, in the for hands for better bur- Wildlands Alliance’s watershed, using tables groundwater, on the soil rowing ability. -

Selected Resources for Understanding Racism

Selected Resources for Understanding Racism The 21st century has witnessed an explosion of efforts – in literature, art, movies, television, and other forms of communication—to explore and understand racism in all of its many forms, as well as a new appreciation of similar works from the 20th century. For those interested in updating and deepening their understanding of racism in America today, the Anti-Racism Group of Western Presbyterian Church has collaborated with the NCP MCC Race and Reconciliation Team to put together an annotated sampling of these works as a guide for individual efforts at self-development. The list is not definitive or all-inclusive. Rather, it is intended to serve as a convenient reference for those who wish to begin or continue their journey towards a greater comprehension of American racism. February 2020 Contemporary Alexander, Michelle. 2010. The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness. Written by a civil rights litigator, this book discusses race-related issues specific to African-American males and mass incarceration in the United States. The central premise is that "mass incarceration is, metaphorically, the New Jim Crow". Anderson, Carol. 2017. White Rage. From the Civil War to our combustible present, White Rage reframes our continuing conversation about race, chronicling the powerful forces opposed to black progress in America. Asch, Chris Myers and Musgrove, George Derek. 2017. Chocolate City: A History of Race and Democracy in the Nation's Capital. A richly researched and clearly written analysis of the history of racism in Washington, DC, from the 18th century to the present, and the efforts of people of color to claim a voice in local government decisionmaking. -

NPR ISSUES/PROGRAMS (IP REPORT) - September 1, 2016 Through September 30, 2016 Subject Key No

NPR ISSUES/PROGRAMS (IP REPORT) - September 1, 2016 through September 30, 2016 Subject Key No. of Stories per Subject AGING AND RETIREMENT 14 AGRICULTURE AND ENVIRONMENT 103 ARTS AND ENTERTAINMENT 187 includes Sports BUSINESS, ECONOMICS AND FINANCE 97 CRIME AND LAW ENFORCEMENT 153 EDUCATION 27 includes College IMMIGRATION AND REFUGEES 33 MEDICINE AND HEALTH 67 includes Health Care & Health Insurance MILITARY, WAR AND VETERANS 37 POLITICS AND GOVERNMENT 346 RACE, IDENTITY AND CULTURE 133 RELIGION 12 SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY 68 Total Story Count 1277 Total duration (hhh:mm:ss) 102:40:34 Program Codes (Pro) Code No. of Stories per Show All Things Considered AT 604 Fresh Air FA 35 Morning Edition ME 451 TED Radio Hour TED 8 Weekend Edition WE 179 Total Story Count 1277 Total duration (hhh:mm:ss) 102:40:34 AT, ME, WE: newsmagazine featuring news headlines, interviews, produced pieces, and analysis FA: interviews with newsmakers, authors, journalists, and people in the arts and entertainment industry TED: excerpts and interviews with TED Talk speakers centered around a common theme Key Pro Date Duration Segment Title Aging and Retirement ALL THINGS CONSIDERED 09/01/2016 0:03:53 Dallas Police Chief David Brown Announces Retirement Aging and Retirement MORNING EDITION 09/01/2016 0:02:35 In Visit With Seniors, This Boy Learned Lessons That Go Beyond The Classroom Aging and Retirement WEEKEND EDITION SATURDAY 09/03/2016 0:05:26 After Almost 30 Years As Covering American Politics, Ron Fournier Heads Home Aging and Retirement WEEKEND EDITION SATURDAY -

NPR ISSUES/PROGRAMS (IP REPORT) - March 1, 2021 Through March 31, 2021 Subject Key No

NPR ISSUES/PROGRAMS (IP REPORT) - March 1, 2021 through March 31, 2021 Subject Key No. of Stories per Subject AGING AND RETIREMENT 5 AGRICULTURE AND ENVIRONMENT 76 ARTS AND ENTERTAINMENT 149 includes Sports BUSINESS, ECONOMICS AND FINANCE 103 CRIME AND LAW ENFORCEMENT 168 EDUCATION 42 includes College IMMIGRATION AND REFUGEES 51 MEDICINE AND HEALTH 171 includes Health Care & Health Insurance MILITARY, WAR AND VETERANS 26 POLITICS AND GOVERNMENT 425 RACE, IDENTITY AND CULTURE 85 RELIGION 19 SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY 79 Total Story Count 1399 Total duration (hhh:mm:ss) 125:02:10 Program Codes (Pro) Code No. of Stories per Show All Things Considered AT 645 Fresh Air FA 41 Morning Edition ME 513 TED Radio Hour TED 9 Weekend Edition WE 191 Total Story Count 1399 Total duration (hhh:mm:ss) 125:02:10 AT, ME, WE: newsmagazine featuring news headlines, interviews, produced pieces, and analysis FA: interviews with newsmakers, authors, journalists, and people in the arts and entertainment industry TED: excerpts and interviews with TED Talk speakers centered around a common theme Key Pro Date Duration Segment Title Aging and Retirement ALL THINGS CONSIDERED 03/23/2021 0:04:22 Hit Hard By The Virus, Nursing Homes Are In An Even More Dire Staffing Situation Aging and Retirement WEEKEND EDITION SATURDAY 03/20/2021 0:03:18 Nursing Home Residents Have Mostly Received COVID-19 Vaccines, But What's Next? Aging and Retirement MORNING EDITION 03/15/2021 0:02:30 New Orleans Saints Quarterback Drew Brees Retires Aging and Retirement MORNING EDITION 03/12/2021 0:05:15 -

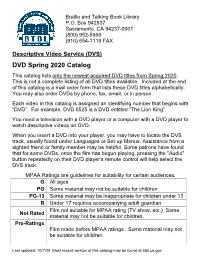

DVD Spring 2020 Catalog This Catalog Lists Only the Newest Acquired DVD Titles from Spring 2020

Braille and Talking Book Library P.O. Box 942837 Sacramento, CA 94237-0001 (800) 952-5666 (916) 654-1119 FAX Descriptive Video Service (DVS) DVD Spring 2020 Catalog This catalog lists only the newest acquired DVD titles from Spring 2020. This is not a complete listing of all DVD titles available. Included at the end of this catalog is a mail order form that lists these DVD titles alphabetically. You may also order DVDs by phone, fax, email, or in person. Each video in this catalog is assigned an identifying number that begins with “DVD”. For example, DVD 0525 is a DVD entitled “The Lion King”. You need a television with a DVD player or a computer with a DVD player to watch descriptive videos on DVD. When you insert a DVD into your player, you may have to locate the DVS track, usually found under Languages or Set-up Menus. Assistance from a sighted friend or family member may be helpful. Some patrons have found that for some DVDs, once the film has begun playing, pressing the "Audio" button repeatedly on their DVD player's remote control will help select the DVS track. MPAA Ratings are guidelines for suitability for certain audiences. G All ages PG Some material may not be suitable for children PG-13 Some material may be inappropriate for children under 13 R Under 17 requires accompanying adult guardian Film not suitable for MPAA rating (TV show, etc.) Some Not Rated material may not be suitable for children. Pre-Ratings Film made before MPAA ratings. Some material may not be suitable for children. -

Studio Movie Grill Supports the Education Community As the Hate U Give #Dayofdialogue Ambassador

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Press inquiries to BazanPR: Jackie Bazan/[email protected] Evelyn Santana/[email protected] STUDIO MOVIE GRILL SUPPORTS THE EDUCATION COMMUNITY AS THE HATE U GIVE #DAYOFDIALOGUE AMBASSADOR Hosts Free In-Theater Events for Teachers and Students at Locations Around the Country Dallas, Texas – October 25, 2018 –Studio Movie Grill (SMG) the leader of the in-theater dining concept operating 314 screens in 30 locations nationwide, today announced it will welcome more than 3,500 teachers and students from school districts in and around the communities they serve for an SMG Movies + Meals #DAYOFDIALOGUE with THE HATE U GIVE, the acclaimed motion picture based on Angie Thomas’ best-selling novel. SMG’s #DAYOFDIALOGUE will take place on October 29th at 11:00 AM in each respective participating city. All participating schools will receive free tickets to see the film and free lunch provided to all attendees. Hosted in partnership with educational outreach firm BazanED, and supported by BazanED’s full free companion curriculum for in-school use, the collaboration is designed to enhance students’ knowledge of race relations, empower student voice and strengthen communities. The joint effort highlights one of many ways the business community at large can support teachers and students in their communities. “What better way for our SMG teams to live our mission, to open hearts and minds, one story at a time, than to make an impact by wholeheartedly supporting this important film and offering our theaters for a continuing conversation between educators and students as part of our ongoing outreach and Movies + Meals program?” says Brian Schultz Founder/CEO, Studio Movie Grill. -

We'll Keep You Rolling Along

4B The herald-News wedNesday, JuNe 17, 2020 TV Guide Listings June 17 - June 23 Ky. Campuses, Education Groups A-DirecTV;B-Dish;C-Brandenburg JUNE 17, 2020 SUNDAYWEEKDAY EVENING AFTERNOONS A-DirecTV;B-Dish;C-Brandenburg JUNE 21, 2020 A B C 12:00 12:30 1:00 1:30 2:00 2:30 3:00 3:30 4:00 4:30 5:00 A B C 6:00 6:30 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 Kick Off FAFSA Fridays Campaign 3/WAVE 3 3 3 Days of our Lives Caught Live PD WAVE 3 News WAVE 3 News News News News 3/WAVE 3 3 3 Game Night The Titan Games America’s Got Talent “Auditions 4” WAVE 3 News Greta 7/WTVW News Andy G. Hot Hot Varied Jerry Jerry Springer People’s Court Judge 7/WTVW News Andy G. DC’s Stargirl (S) Supergirl News Theory Family Family FRANKFORT– Kentucky colleges and for college, and ultimately, a successful ca- 9/WNIN Sesame Varied Programs Go Luna Nature ÅWild Molly Xavier Odd Arthur Splash 9/WNIN Prehistoric-Trip Royal Myths Grantchester Beecham House Across the Pacifi c Royal universities along with key leaders in edu- reer. Stakeholders will drive that message 11/WHAS 11 11 11 Pandemic-You General Hospital Blast Blast WHAS11 News News News News 11/WHAS 11 11 11 Celebrity Fam John Legend Press Your Luck Match Game (S) News Osteen NCIS 23/WKZT 4 Varied Programs Pink Dino Cat in Nature Odd Arthur Varied cation launched a new public awareness home every week through the campaign, he 23/WKZT 4 Shakespeare Royal Myths Grantchester Beecham House Modus (S) Wine 32/WLKY 32 32 5 25 Bold The Talk Tamron Hall Young & Restless News NewsÅ News campaign – called FAFSA Fridays – to re- said. -

(LACMA) Hosted Its Ninth Annual Art+Film Gala on Saturday, November 2, 2019, Honoring Artist Betye Saar and Filmmaker Alfonso Cuarón

(Los Angeles, November 3, 2019)—The Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) hosted its ninth annual Art+Film Gala on Saturday, November 2, 2019, honoring artist Betye Saar and filmmaker Alfonso Cuarón. Co-chaired by LACMA trustee Eva Chow and actor Leonardo DiCaprio, the evening brought together more than 800 distinguished guests from the art, film, fashion, and entertainment industries, among others. This year’s gala raised more than $4.6 million, with proceeds supporting LACMA’s film initiatives and future exhibitions, acquisitions, and programming. The 2019 Art+Film Gala was made possible through Gucci’s longstanding and generous partnership. Additional support for the gala was provided by Audi. Eva Chow, co-chair of the Art+Film Gala, said, “I’m so happy that we have outdone ourselves again with the most successful Art+Film Gala yet. It was such a joy to celebrate Betye Saar and Alfonso Cuarón’s incredible creativity and passion, while supporting LACMA’s art and film initiatives. I couldn’t be more grateful to Alessandro Michele, Marco Bizzarri, and everyone at Gucci—our invaluable partner since the first Art+Film Gala—and to Anderson .Paak and The Free Nationals for making this evening one to remember.” “I’m deeply grateful to our returning co-chairs Eva Chow and Leonardo DiCaprio for helping us set another Art+Film Gala record,” said Michael Govan, LACMA CEO and Wallis Annenberg Director. “We honored two incredibly powerful artistic voices this year. Betye Saar has helped define the genre of Assemblage art for nearly seven decades, and recognition of her as one of the most important and influential artists working today is long overdue. -

Magazine for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual , Trans and Questioning Young People

g - Zine Magazine for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual , Trans and Questioning young people. Celebrating Providing 40 years of support for LGBTQ+ Young People in Liverpool! Produced by the young people of GYRO & T.A.Y 1 About The g-Zine In this Issue G-Zine has been created and produced by young people from GYRO and The Action Youth. It’s by LGBTQ+ young people for LGBTQ+ What is the G - Zine.............................................................. Page 3 young people, it’s full of advice, stories, reviews, guides and useful stuff. LGBT+ History ...................................................................... Page 4 We hope you like it! Coming Out - My Story.......................................................... Page 6 Coming Out Tips and Advice................................................ Page 7 Getting to Know Gyro - Chris................................................ Page 9 Let’s Talk About Sexuality.................................................... Page 10 Pronouns - What’s in a word?................................................. Page 12 #TDOV - Transgender Day of Visibility................................. Page 13 Agony Fam - Advice............................................................... Page 14 Image Credit - Kai LGBT+ Bookshelf................................................................... Page 16 Sexual Health........................................................................ Page 18 Image Credit - Lois Tierney Illustration Movie Reviews - Watercolours............................................. -

Being Black and Being Beautiful. Der Einfluss Von Haar Und Frisur Auf

Being Black and being beautiful: Der Einfluss von Haar und Frisur auf das Leben Schwarzer Frauen Joy Amaka Onyemaechi 8b GRG 10 Ettenreichgasse Betreuerin: Mag. Christina Gerger 3. Februar 2021 Abstract Seit Jahrhunderten wird das Leben Schwarzer Menschen von vorherrschenden europäischen Schönheitsidealen und rassistischem Denken negativ beeinträchtigt. Besonders davon betroffen sind Schwarze Frauen, welche auch aufgrund Ihrer Haare von klein auf diskriminiert werden. Diese Arbeit zeigt einerseits, wie es zu dieser Unterdrückung kam und welche Auswirkungen das Aufwachsen als Angehörige bzw. Angehöriger der Schwarzen Minderheit in der Weißen Mehrheitsgesellschaft hat. Andererseits stellt sie dar, welche Bewegungen gegen diese rassistische Diskriminierung entstanden sind. Besonders wird dabei auf die Bedeutung der Natural Hair Bewegung eingegangen. Inhaltsverzeichnis 1 Einleitung ...................................................................................................................... 1 2 Haar und Frisur im kulturgeschichtlichen Kontext .......................................................... 2 2.1 Das europäische Schönheitsideal ............................................................................. 2 2.2 Haar und Frisur im geschichtlichen Kontext in afrikanischen Kulturen .................... 4 3 Eurozentrismus und Rassismus ...................................................................................... 6 3.1 Von der Aufklärung zur Rassenlehre ...................................................................... -

"Get in Formation:" a Black Feminist Analysis of Beyonce's Visual Album, Lemonade Sina H

Eastern Michigan University DigitalCommons@EMU Senior Honors Theses Honors College 2018 When Life Gives You Lemons, "Get In Formation:" A Black Feminist Analysis of Beyonce's Visual Album, Lemonade Sina H. Webster Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.emich.edu/honors Part of the Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons Recommended Citation Webster, Sina H., "When Life Gives You Lemons, "Get In Formation:" A Black Feminist Analysis of Beyonce's Visual Album, Lemonade" (2018). Senior Honors Theses. 568. https://commons.emich.edu/honors/568 This Open Access Senior Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors College at DigitalCommons@EMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@EMU. For more information, please contact lib- [email protected]. When Life Gives You Lemons, "Get In Formation:" A Black Feminist Analysis of Beyonce's Visual Album, Lemonade Abstract Beyonce's visual album, Lemonade, has been considered a Black feminist piece of work because of the ways in which it centralizes the experiences of Black women, including their love relationships with Black men, their relationships with their mothers and daughters, and their relationships with other Black women. The album shows consistent themes of motherhood, the "love and trouble tradition," and Afrocentrism. Because of its hint of Afrocentrism, however, Lemonade can be argued as an anti Black feminist work because Afrocentrism holds many sexist beliefs of Black women. This essay will discuss the ways in which Lemonade's inextricable influences of Black feminism and Afrocentrism, along with other anti Black feminist notions, can be used as a consciousness-raising tool.