Charles Maurras and His Influence on Right-Wing Political

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CRITICAL THEORY and AUTHORITARIAN POPULISM Critical Theory and Authoritarian Populism

CDSMS EDITED BY JEREMIAH MORELOCK CRITICAL THEORY AND AUTHORITARIAN POPULISM Critical Theory and Authoritarian Populism edited by Jeremiah Morelock Critical, Digital and Social Media Studies Series Editor: Christian Fuchs The peer-reviewed book series edited by Christian Fuchs publishes books that critically study the role of the internet and digital and social media in society. Titles analyse how power structures, digital capitalism, ideology and social struggles shape and are shaped by digital and social media. They use and develop critical theory discussing the political relevance and implications of studied topics. The series is a theoretical forum for in- ternet and social media research for books using methods and theories that challenge digital positivism; it also seeks to explore digital media ethics grounded in critical social theories and philosophy. Editorial Board Thomas Allmer, Mark Andrejevic, Miriyam Aouragh, Charles Brown, Eran Fisher, Peter Goodwin, Jonathan Hardy, Kylie Jarrett, Anastasia Kavada, Maria Michalis, Stefania Milan, Vincent Mosco, Jack Qiu, Jernej Amon Prodnik, Marisol Sandoval, Se- bastian Sevignani, Pieter Verdegem Published Critical Theory of Communication: New Readings of Lukács, Adorno, Marcuse, Honneth and Habermas in the Age of the Internet Christian Fuchs https://doi.org/10.16997/book1 Knowledge in the Age of Digital Capitalism: An Introduction to Cognitive Materialism Mariano Zukerfeld https://doi.org/10.16997/book3 Politicizing Digital Space: Theory, the Internet, and Renewing Democracy Trevor Garrison Smith https://doi.org/10.16997/book5 Capital, State, Empire: The New American Way of Digital Warfare Scott Timcke https://doi.org/10.16997/book6 The Spectacle 2.0: Reading Debord in the Context of Digital Capitalism Edited by Marco Briziarelli and Emiliana Armano https://doi.org/10.16997/book11 The Big Data Agenda: Data Ethics and Critical Data Studies Annika Richterich https://doi.org/10.16997/book14 Social Capital Online: Alienation and Accumulation Kane X. -

Download the Classification Decision for the Great

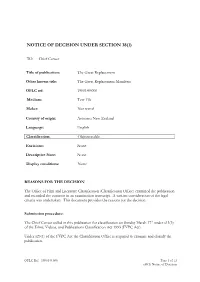

NOTICE OF DECISION UNDER SECTION 38(1) TO: Chief Censor Title of publication: The Great Replacement Other known title: The Great Replacement Manifesto OFLC ref: 1900149.000 Medium: Text File Maker: Not stated Country of origin: Aotearoa New Zealand Language: English Classification: Objectionable. Excisions: None Descriptive Note: None Display conditions: None REASONS FOR THE DECISION The Office of Film and Literature Classification (Classification Office) examined the publication and recorded the contents in an examination transcript. A written consideration of the legal criteria was undertaken. This document provides the reasons for the decision. Submission procedure: The Chief Censor called in this publication for classification on Sunday March 17th under s13(3) of the Films, Videos, and Publications Classification Act 1993 (FVPC Act). Under s23(1) of the FVPC Act the Classification Office is required to examine and classify the publication. OFLC Ref: 1900149.000 Page 1 of 13 s38(1) Notice of Decision Under s23(2) of the FVPC Act the Classification Office must determine whether the publication is to be classified as unrestricted, objectionable, or objectionable except in particular circumstances. Section 23(3) permits the Classification Office to restrict a publication that would otherwise be classified as objectionable so that it can be made available to particular persons or classes of persons for educational, professional, scientific, literary, artistic, or technical purposes. Synopsis of written submission(s): No submissions were required or sought in relation to the classification of the text. Submissions are not required in cases where the Chief Censor has exercised his authority to call in a publication for examination under section 13(3) of the FVPC Act. -

How White Supremacy Returned to Mainstream Politics

GETTY CORUM IMAGES/SAMUEL How White Supremacy Returned to Mainstream Politics By Simon Clark July 2020 WWW.AMERICANPROGRESS.ORG How White Supremacy Returned to Mainstream Politics By Simon Clark July 2020 Contents 1 Introduction and summary 4 Tracing the origins of white supremacist ideas 13 How did this start, and how can it end? 16 Conclusion 17 About the author and acknowledgments 18 Endnotes Introduction and summary The United States is living through a moment of profound and positive change in attitudes toward race, with a large majority of citizens1 coming to grips with the deeply embedded historical legacy of racist structures and ideas. The recent protests and public reaction to George Floyd’s murder are a testament to many individu- als’ deep commitment to renewing the founding ideals of the republic. But there is another, more dangerous, side to this debate—one that seeks to rehabilitate toxic political notions of racial superiority, stokes fear of immigrants and minorities to inflame grievances for political ends, and attempts to build a notion of an embat- tled white majority which has to defend its power by any means necessary. These notions, once the preserve of fringe white nationalist groups, have increasingly infiltrated the mainstream of American political and cultural discussion, with poi- sonous results. For a starting point, one must look no further than President Donald Trump’s senior adviser for policy and chief speechwriter, Stephen Miller. In December 2019, the Southern Poverty Law Center’s Hatewatch published a cache of more than 900 emails2 Miller wrote to his contacts at Breitbart News before the 2016 presidential election. -

Reflections on Russell Kirk Lee Trepanier Saginaw Valley State University

Russell Kirk: A Centennial Symposium Reflections on Russell Kirk Lee Trepanier Saginaw Valley State University A century has passed since the birth of Russell Kirk (1918-94), one of the principal founders of the post-World War II conservative revival in the United States.1 This symposium examines Kirk’s legacy with a view to his understanding of constitutional law and the American Founding. But before we examine these essays, it is worth a moment to review Kirk’s life, thought, and place in American conservatism. Russell Kirk was born and raised in Michigan and obtained his B.A. in history at Michigan State University and his M.A. at Duke Univer- sity, where he studied John Randolph of Roanoke and discovered the writings of Edmund Burke.2 His book Randolph of Roanoke: A Study in Conservative Thought (1951) would endure as one of his most important LEE TREPANIER is Professor of Political Science at Saginaw Valley State University. He is also the editor of Lexington Books’ series “Politics, Literature, and Film” and of the aca- demic website VoegelinView. 1 I would like to thank the McConnell Center at the University of Louisville for sponsoring a panel related to this symposium at the 2018 American Political Science Conference and Zachary German for his constructive comments on these papers. I also would like to thank Richard Avramenko of the Center for the Study of Liberal Democracy at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, and Saginaw Valley State University for supporting my sabbatical, which enabled me to write this article and organize this symposium for Humanitas. -

Charles Maurras Le Nationaliste Intégral Dans La Même Collection

Olivier Dard Charles Maurras Le nationaliste intégral Dans la même collection Brian Cox, Jeff Forshaw, L’univers quantique. Tout ce qui peut arriver arrive..., 2018 Marianne Freiberger, Rachel A. Thomas, Dans le secret des nombres, 2018 Xavier Mauduit, Corinne Ergasse, Flamboyant Second Empire. Et la France entra dans la modernité..., 2018 Natalie Petiteau, Napoléon Bonaparte. La nation incarnée, 2019 Jacques Portes, La véritable histoire de l’Ouest américain, 2018 Thomas Snégaroff, Kennedy. Une vie en clair-obscur, 2017 Thomas Snégaroff, Star Wars. Le côté obscur de l’Amérique, 2018 Max Tegmark, Notre univers mathématique. En quête de la nature ultime du réel, 2018 Maquette de couverture : Delphine Dupuy ©Armand Colin, Paris, 2013, Dunod, 2019 ISBN : 978-2-10-079376-1 Du même auteur Avec Ana Isabel Sardinha-Desvignes, Célébrer Salazar en France (1930-1974). Du philosalazarisme au salazarisme français, PIE-Peter Lang, coll. «Convergences», 2018. La synarchie : le mythe du complot permanent, Perrin, coll. « Tempus », 2012 [1998]. Voyage au cœur de l’OAS, Perrin, coll. « Synthèses historiques », 2011 [2005]. Bertrand de Jouvenel, Perrin, 2008. Le rendez-vous manqué des relèves des années trente, PUF, coll. « Le nœud gordien », 2002. La France contemporaine, vol. 5, Les années 30 : le choix impossible, LGF, coll. « Livre de poche, Références histoire », 1999. Jean Coutrot, de l’ingénieur au prophète, Presses universitaires franc-comtoises, coll. « Annales littéraires de l’Université de Franche-Comté », 1999. Remerciements Si, selon la formule consacrée, les propos de cet ouvrage n’engagent que leur auteur, ils sont aussi le fruit de nom- breux échanges individuels et de réflexions collectives. Mes premiers remerciements vont à deux collègues et amis, Michel Grunewald et Michel Leymarie, qui ont suivi la rédaction de ce manuscrit et été des relecteurs très précieux. -

The Educational Ideas of Irving Babbitt

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 1974 The ducE ational Ideas of Irving Babbitt: Critical Humanism and American Higher Education Joseph Aldo Barney Loyola University Chicago Recommended Citation Barney, Joseph Aldo, "The ducaE tional Ideas of Irving Babbitt: Critical Humanism and American Higher Education" (1974). Dissertations. Paper 1363. http://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss/1363 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 1974 Joseph Aldo Barney The Educational Ideas of Irving Babbitt: Critical Humanism and .American Higher Education by Joseph Aldo Barney A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Loyola University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy February 1974 VITA Joseph Aldo Barney was born January 11, 1940 in the city of Chicago. He attended Our Lady Help of Christians Grammar School, Sto Mel High School and, in 1967, received the degree of Bachelor of Science from Loyola University of Chicago. During the period 1967 to present, Mr. Barney continued his studies at Loyola University, earning the degree of Master of Education in 1970 and the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in 1974. Mr. Barney's occupational pursuits have centered about university administration and teachingo He was employed by Loyola University of Chicago from 1961 to 1973 in various administrative capacities. -

Unlversiv Micrijfilms Intemationéü 300 N

INFORMATION TO USERS This was produced from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or “target” for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is “Missing Page(s)”. If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the fîlm along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure you of complete continuity. 2. When an image on the Him is obliterated with a round black mark it is an indication that the film inspector noticed either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, or duplicate copy. Unless we meant to delete copyrighted materials that should not have been fîlmed, you will And a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., is part of the material being photo graphed the photographer has followed a defînite method in “sectioning” the material. It is customary to begin filming at the upper left hand comer of a large sheet and to continue from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. If necessary, sectioning is continued again—beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. For any illustrations that cannot be reproduced satisfactorily by xerography, photographic prints can be purchased at additional cost and tipped into your xerographic copy. -

Different Shades of Black. the Anatomy of the Far Right in the European Parliament

Different Shades of Black. The Anatomy of the Far Right in the European Parliament Ellen Rivera and Masha P. Davis IERES Occasional Papers, May 2019 Transnational History of the Far Right Series Cover Photo: Protesters of right-wing and far-right Flemish associations take part in a protest against Marra-kesh Migration Pact in Brussels, Belgium on Dec. 16, 2018. Editorial credit: Alexandros Michailidis / Shutter-stock.com @IERES2019 Different Shades of Black. The Anatomy of the Far Right in the European Parliament Ellen Rivera and Masha P. Davis IERES Occasional Papers, no. 2, May 15, 2019 Transnational History of the Far Right Series Transnational History of the Far Right Series A Collective Research Project led by Marlene Laruelle At a time when global political dynamics seem to be moving in favor of illiberal regimes around the world, this re- search project seeks to fill in some of the blank pages in the contemporary history of the far right, with a particular focus on the transnational dimensions of far-right movements in the broader Europe/Eurasia region. Of all European elections, the one scheduled for May 23-26, 2019, which will decide the composition of the 9th European Parliament, may be the most unpredictable, as well as the most important, in the history of the European Union. Far-right forces may gain unprecedented ground, with polls suggesting that they will win up to one-fifth of the 705 seats that will make up the European parliament after Brexit.1 The outcome of the election will have a profound impact not only on the political environment in Europe, but also on the trans- atlantic and Euro-Russian relationships. -

O Desenvolvimento Da Extrema Direita Na França E a Formação Do Front National

O desenvolvimento da extrema direita na França e a formação do Front National The development of the extreme right in France and the formation of the Front National Guilherme Ignácio Franco de Andrade1 Mestrando em História Universidade Estadual do Oeste do Paraná – Unioeste [email protected] Artigos Recebido em: 18/03/2014 Aprovado em: 28/08/2014 RESUMO: O artigo tem a intenção de investigar o crescimento dos movimentos de extrema direita na Europa e a radicalização do pensamento político, procurando desenvolver de forma sintética o processo histórico ocorrido na França. Podemos observar que a constituição da ideologia de extrema direita passa por diversas transformações ao longo dos últimos dois séculos, registrando avanços em popularidade em alguns momentos, mas também apresentando diversas vezes um retrocesso nos projetos elaborados pelos movimentos radicais, que o levaram ao próprio fracasso e destruição. O objetivo do artigo é fazer um levantamento historiográfico sobre o processo de formação e consolidação da extrema direita na França, visto que hoje o país apresenta um dos maiores partidos de extrema direita, o Front National, liderado por Marine Le Pen. PALAVRAS-CHAVE: Extrema direita, Fascismo, França. ABSTRACT: The following article intends to investigate the growth of far-right movements in Europe and the radicalization of political thought, trying to develop synthetic forms the historical process occurred in France. We can observe that the constitution of the ideology of the extreme right goes through several transformations over the past two centuries, logging advances in popularity in some moments, but also presenting several times a setback in projects prepared by radical movements that led to the failure itself and destruction. -

3:HIKLKJ=XUXUUU:?C@Q@J@K@A;

2 N° 2690 L’ACTION 0 58e année du 1er au 14 0 décembre 2005 Prix : 3s (20 F) FRANÇAISE 0 paraît provisoirement les premier et troisième jeudis de chaque mois 10, rue Croix-des-Petits-Champs, 75001 Paris – Téléphone : 01-40-39-92-06 – Fax : 01-40-26-31-63 – Site Internet : www.actionfrancaise.net Tout ce qui est national est nôtre Notre dossier APRES LES ÉMEUTES LA LOI DE 1905 : UN LOURD BILAN Par Michel FROMENTOUX Pierre PUJO Entretien avec Jean SEVILLIA Il va falloir (pages 7 à 9) L'ESSENTIEL Page 2 POLITIQUE FRANÇAISE – La face cachée de la crise des banlieues payer la facture par Ahmed RACHID CHEKROUN – Être français n'est pas un droit ! L’éditorial de Pierre PUJO (page 3) par Aristide LEUCATE – La république à court terme par Henri LETIGRE LE MASSACRE DES GARDES SUISSES AUX TUILERIES – L’Université du Club de l’Horloge par Pierre PUJO Quand la République a honte de ses origines Pages 4, 5 et 6 LE BANQUET e président de la Confé- s'est entretenu durant une heure abstenu de tout commentaire. voilé au Musée de l'Armée, à DU 13 NOVEMBRE dération helvétique et par avec Jacques Chirac. Le temps Sans doute était-il soucieux. Car l'hôtel des Invalides, une plaque – Présence Lailleurs ministre de la Dé- d'évoquer les relations bilaté- il lui restait à accomplir une mis- rappelant le sacrifice des gardes de l'Action française fense, Samuel Schmid, a effec- rales, notamment en matière de sion ingrate, un devoir de mé- suisses. La réalité est sensible- par Jacques CEPOY tué le 18 novembre dernier une coopération transfrontalière et moire qu'à sa grande déconve- ment différente. -

Die Action Française

ERNST NOLTE DIE ACTION FRANCAISE 1899-1944 Die Action francaise ist aus der Dreyfus-Affäre entstanden, wie die Regierungs beteiligung der Sozialisten, die Trennung von Staat und Kirche, die reelle Unter stellung der militärischen Gewalt unter die zivile aus dieser unblutigsten aller Revolutionen1 hervorgegangen sind. Aber auch die Differenzierung von Sozialismus und Kommunismus, die Entstehung des Zionismus und die Ausbildung der letzten gedanklichen Konsequenzen des Antisemitismus2 sind mit der Affäre mehr oder minder deutlich verknüpft. Mit ihr beginnt in Frankreich das XX. Jahrhundert, das im übrigen Europa erst mit dem Weltkrieg seinen Anfang nimmt3. Die Action francaise kann in diesem Zusammenhang nur dann von bedeutendem Interesse sein, wenn in ihr bereits wesentliche Züge der späteren, zu Recht oder zu Unrecht „faschistisch" genannten politischen Phänomene präformiert sind, wenn sie also in gewisser Hinsicht selbst schon ein Faschismus ist: der erste von allen. Eben diese Vermutung aber stößt auf die ernsthaftesten Bedenken4. Bleibt der Rationalismus der Action francaise nicht weit entfernt von jenem ungestümen Irrationalismus, der später in Italien und in Deutschland das Handeln so gut wie das Denken zu beherrschen scheint? Ist sie als kleine, für die parlamentarische Kräfteverteilung bedeutungslose Gruppe von Intellektuellen nicht ganz anderer Natur als die gewaltigen Massenbewegungen des italienischen Faschismus und des deutschen Nationalsozialismus? Ist ihr Monarchismus, ihre konservative und gegen revolutionäre Tendenz nicht geradezu das Gegenteil des revolutionären Verände rungswillens, der Hitler und Mussolini in einen gnadenlosen Kampf mit den kon servativen Kräften ihrer Länder führte? Diese Fragen sind ohne eine umfassende Analyse der Ideologien, der Organisa tionsformen und Aktionstendenzen nicht zu klären; sie dürfte zur Ausbildung von begrifflichen Unterscheidungen führen, die sich ebenso entfernt zu halten 1 Vgl. -

Reading Houellebecq and His Fictions

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2018 Reading Houellebecq And His Fictions Sterling Kouri University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Recommended Citation Kouri, Sterling, "Reading Houellebecq And His Fictions" (2018). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 3140. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/3140 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/3140 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Reading Houellebecq And His Fictions Abstract This dissertation explores the role of the author in literary criticism through the polarizing protagonist of contemporary French literature, Michel Houellebecq, whose novels have been both consecrated by France’s most prestigious literary prizes and mired in controversies. The polemics defining Houellebecq’s literary career fundamentally concern the blurring of lines between the author’s provocative public persona and his work. Amateur and professional readers alike often assimilate the public author, the implied author and his characters, disregarding the inherent heteroglossia of the novel and reducing Houellebecq’s works to thesis novels necessarily expressing the private opinions and prejudices of the author. This thesis explores an alternative approach to Houellebecq and his novels. Rather than employing the author’s public figure to read his novels, I proceed in precisely the opposite