Effect of Consumption of the Nutrient-Dense, Freshwater Small fish

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(PSI) Project Name Mymensingh Kewatkhali Bridge Project Country

Project Number: 000163 Project Summary Information (PSI) Project Name Mymensingh Kewatkhali Bridge Project Country People’s Republic of Bangladesh Sector Transport Project No. 0000163 Borrower People’s Republic of Bangladesh Implementation Agency Ministry of Road Transport and Bridges Environmental and Social Category A Date of PSI prepared or updated Sep. 5, 2018 Date of Concept Decision Approved on Sep. 4, 2018 Estimated Date of Board Consideration Aug., 2019 I. Introduction Mymensingh Kewatkhali Bridge is part of the Dhaka-Mymensingh-India border corridor, which is strategically important for both regional and local connectivity. Three land ports have been developed along the Indian border in Mymensingh Division, namely Nakugaon Land port in Sherpur district, Gobrakura Land Port and Haluaghat Land Port in Mymensingh District. Traffic from the three land ports must cross Old Brahmaputra River at Mymensingh City in order to reach Dhaka and other parts of Bangladesh. As with other land ports on the northern border with India, the main import items are coal, lime stone, boulder, stone, glass sand, fruits and raw hides. Export items are food and beverage items, plastic goods and bricks. Given the proximity to the Indian border (around 60-80 km from Mymensingh to the three land ports), the road passing through Mymensingh serves international trade by carrying the major import/export items from/to India. The improved crossing at Mymensingh will help facilitate cross-border trade with northeast India. On the other hand, the Mymensingh Kewatkhali bridge will provide crossing over the Old Brahmaputra River to connect the landlocked north central and northeast Bangladesh with Dhaka. -

Do Political Economy Factors Influence Funding Allocations for Disaster Risk Reduction?

Journal of Risk and Financial Management Article Do Political Economy Factors Influence Funding Allocations for Disaster Risk Reduction? Shafiqul Islam 1,*, Khondker Mohammad Zobair 2, Cordia Chu 3, James C. R. Smart 1 and Md Samsul Alam 4 1 School of Environment and Science, Griffith University, Nathan, QLD 4111, Australia; j.smart@griffith.edu.au 2 Business School, Griffith University, Nathan, QLD 4111, Australia; k.zobair@griffith.edu.au 3 Centre for Environment and Population Health, School of Medicine, Griffith University, Nathan, QLD 4111, Australia; c.chu@griffith.edu.au 4 Leicester Castle Business School, De Montfort University, Leicester LE1 9BH, UK; [email protected] * Correspondence: shafiqul.islam@griffithuni.edu.au Abstract: Considering the importance of political economy in implementing Disaster Risk Reduction (DRR), this research investigates the significance of political economy in the distribution of DRR funding in Bangladesh. The study analysed data from self-reported surveys from 133 members of the sub-district level disaster management committee and government officials working with DRR. Employing the Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) method, we find that political economy factors explain 68% of the variance in funding allocations. We also show that four categories of political economy factors—power and authority, interest and incentives, institutions, and values and ideas—are significantly influential over the distribution of DRR funding across subdistricts of Bangladesh. Our findings offer important policy implications to reduce the potential risks surrounding political economy influences in fund allocation and advance climate Citation: Islam, Shafiqul, Khondker finance literature. Mohammad Zobair, Cordia Chu, James C. R. -

Cropping Patterns in Mymensingh Region: Diversity, Constraint and Potential

Bangladesh Rice J. 21 (2) : 217-235, 2017 Cropping Patterns in Mymensingh Region: Diversity, Constraint and Potential A Khatun1*, N Parvin1, M M R Dewan2 and A Saha1 ABSTRACT A consistent and comprehensive database on cropping pattern, cropping intensity and crop diversity of a particular area is the prime importance for guiding policy makers, researchers, extentionists and development agencies for the future research and development planning. The study was carried out all the upazilas of Mymensingh region during 2015-16 using pre-designed and pre-tested semi- structured questionnaire with a view to document the existing cropping pattern, crop diversity and cropping intensity. The most dominant cropping pattern Boro−Fallow−T. Aman occupied about one- half of net cropped area (NCA) of the region distributed to 46 out of 47 upazilas. Single Boro cropping pattern ranked the second position which covered 23% of NCA distributed in 45 upazilas. A total of 129 cropping patterns were identified in the whole area of Mymensingh region under this investigation. The highest number of (30) cropping patterns were identified in Pakundia upazila of Kishoreganj and the lowest was (10) in Sreebardi of Sherpur. The lowest crop diversity index (CDI) was reported (0.111) in Mithamoin of Kishoreganj followed by 0.114 at Khaliajuri in Netrokona. The highest value of CDI was observed 0.933 at Dewanganj in Jamalpur followed by 0.920 at Bhairab in Kishoreganj. The range of cropping intensity values was recorded 101-249%. The maximum value was for Hossainpur and minimum for Itna and Mithamoin in Kishoreganj. At a glance the calculated CDI of Mymensingh region was 0.840 and the average cropping intensity was 187%. -

Class: 5 Answer the Following Questions in Own for Questions 1-8 Read the Text and Answer the Questions 1, 2, 3 and 4 My Home District Is Kishoreganj

Class: 5 Answer the following questions in own For Questions 1-8 Read the text and answer the questions 1, 2, 3 and 4 My home district is Kishoreganj. It is about 145 kilometres from Dhaka. It is a district headquarters. The district has 8 municipalities, 13 upazilas, 108 unions and 1745 villages. The name Kishoreganj comes from the name of an old landlord known as Brojakishore Pramanik or Nandakishore Pramanik. The area of Kishoreganj municipality is about 10 square kilometers. The river Narasunda flows through the town. Kishoreganj is a small town, but there are many important places in and around it. The largest Eid fairgrounds called Solakia Eid Ground and the well-known Government Gurudayal College are in the town. People from many districts come to this place to celebrate Eid. The Pagla Mosque is also in many home districts. Outside the town, you can visit the fort of Isah Khan at Jangal Bari. You can also see the Shah Muhammad Mosque at Egaroshidhur. Near the Fuleshwari River, you can see the Shiva Temple of Chandrabati.Kishoreganj is also the home district of some famous people. Chandrabati, the first woman poet of Bangla literature, was born here. Two writers of children's literature, Upendro Kishore Roy Chowdhury and Sukumar Roy are also from here. The great painter Zainul Abedin comes from Kishoreganj, too. Syed Nazrul Islam, the first acting President of Bangladesh, is also from here. I love my home district. 1. Match the words of Column A with their meaning that is mentioned in the text in Column B (there is two extra). -

Horizontal Learning for Strengthening Capacities of Local Government Institutions in Bangladesh

Horizontal Learning for Strengthening Capacities of Local Government Institutions in Bangladesh REPORT ON THE NATIONAL DISSEMINATION WORKSHOP Dhaka, October 30, 2008 Local Government Division Ministry of LGRD & Cooperatives, Government of Bangladesh and Water and Sanitation Program, World Bank, Dhaka Table of Content Page Glossary of abbreviations and terms iv Preface v 1. Introduction 7 2. Inaugural session 9 3. Display on top eight good practices 13 4. Thematic Session-I: Flashback on experiences of horizontal learning 18 Background of preparing the pata song 22 5. Thematic Session-II: Talk show 22 Summary of the talk show 23 6. Summing up and closing - Recommendations for the future 25 Annexures Annexure A: Background 27 Annexure B: Workshop program 31 Annexure C: Participants and resource persons 32 Annexure D: Presentation on thematic session-I 33 GLOSSARY OF ABBREVIATIONS AND TERMS AI Appreciative Inquiry ASEH Advancing Sustainable Environmental Health BDT Bangladesh Taka BUET Bangladesh University of Engineering and Technology CBO Community-based organization DASCOH Development Association for Self-Reliance, Communication and Health Danida Danish International Development Agency Dishari Decentralized Total Sanitation Project DPHE Department of Public Health Engineering Eco-friendly Environment-friendly Gambhira Style of traditional folk song and traditional communication technique ('Alkap',' jari', 'shari', and 'bhatiali' are also some examples of the same thing) Gan Translates as 'song' GoB Government of Bangladesh HL Horizontal -

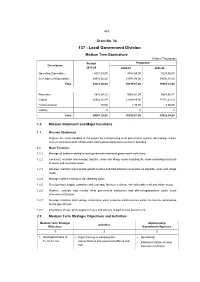

137 - Local Government Division

453 Grant No. 34 137 - Local Government Division Medium Term Expenditure (Taka in Thousands) Budget Projection Description 2019-20 2020-21 2021-22 Operating Expenditure 4321,54,00 4753,69,00 5229,06,00 Development Expenditure 29919,66,00 31541,98,00 34696,18,00 Total 34241,20,00 36295,67,00 39925,24,00 Recurrent 7815,04,16 9003,87,04 8807,80,41 Capital 26425,35,84 27289,84,96 31115,37,59 Financial Asset 80,00 1,95,00 2,06,00 Liability 0 0 0 Total 34241,20,00 36295,67,00 39925,24,00 1.0 Mission Statement and Major Functions 1.1 Mission Statement Improve the living standard of the people by strengthening local government system, developing climate resilient rural and urban infrastructure and implementing socio-economic activities. 1.2 Major Functions 1.2.1 Manage all matters relating to local government and local government institutions; 1.2.2 Construct, maintain and manage Upazilla, union and village roads including the roads and bridges/culverts of towns and municipal areas; 1.2.3 Develop, maintain and manage growth centres and hats-bazaars connected via Upazilla, union and village roads; 1.2.4 Manage matters relating to safe drinking water; 1.2.5 Develop water supply, sanitation and sewerage facilities in climate risk vulnerable rural and urban areas; 1.2.6 Finance, evaluate and monitor local government institutions and offices/organizations under Local Government Division; 1.2.7 Develop, maintain and manage small-scale water resource infrastructures within the timeline determined by the government. 1.2.8 Enactment of Law, promulgation of rules and policies related to local government. -

Is the Price Right? a Study of the Impact of School Fees in Rural

Is the Price Right? A Study of the Impact of School Fees in Rural Bangladesh 29 2 IS THE PRICE RIGHT? A STUDY OF THE IMpaCT OF SCHOOL FEES IN RURAL BANGLADESH Emily Grenzke The purpose of this article is to investigate the effect that user fees have on primary school enrollment and educational at- tainment in rural Bangladesh. There is growing international consensus that school user fees should be abolished in developing countries because they pose a barrier to universal enrollment. However, where school fees are the primary source of revenue for education, abolishing them significantly threatens the quality of education provided. Using data from three different regions in Bangladesh in 1996, this article employs a Heckman model to estimate the determinants of school enrollment. The results suggest that (i) fixed enrollment fees are a barrier to partici- pation in the education market, (ii) but annual fees are not, and (iii) that the cost of secondary education has a significant impact on primary school enrollment. Based on these results, and considering the need for revenue, current policies aimed at abolishing all varieties of school fees are not justified. The article concludes by recommending advocacy for lower fixed enrollment fees and lower fees for secondary schools. 1 INTRODUCTION A 2005 government report on education in Bangladesh given to the South Asian Society for Regional Cooperation recommended that all primary Emily Grenzke is a Master of Public Policy candidate at the Terry Sanford Institute of Public Policy, Duke University ([email protected]). 30 Emily Grenzke school user fees be abolished in the country (Ardt et al 2005, 18-19). -

Land Resource Appraisal of Bangladesh for Agricultural

BGD/81/035 Technical Report 3 Volume II LAND RESOURCES APPRAISAL OF BANGLADESH FOR AGRICULTURAL DEVELOPMENT REPORT 3 LAND RESOURCES DATA BASE VOLUME II SOIL, LANDFORM AND HYDROLOGICAL DATA BASE A /UNITED NATIONS DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMME FAo FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION vJ OF THE UNITED NATIONS BGD/81/035 Technical Report 3 Volume II LAND RESOURCES APPRAISAL OF BANGLADESH FOR AGRICULTURALDEVELOPMENT REPORT 3 LAND RESOURCES DATA BASE VOLUME II SOIL, LANDFORM AND HYDROLOGICAL DATA BASE Report prepared for the Government of the People's Republic of Bangladesh by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations acting as executing agency for the United Nations Development Programme based on the work of H. Brammer Agricultural Development Adviser J. Antoine Data Base Management Expert and A.H. Kassam and H.T. van Velthuizen Land Resources and Agricultural Consultants UNITED NATIONS DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMME FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION OF THE UNITED NATIONS Rome, 1988 The designations employed and the presentation of material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and AgricultureOrganization of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored ina retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopyingor otherwise, without the prior perrnission of (he copyright owner. Applications for such permission,with a statement of the purpose and extent of the reproduction, should be addressedto the Director, Publications Division, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Viadelle Terme di Caracarla, 00100 Home, Italy. -

Livelihood Profiles of Fish Farmers in Kishoreganj, Bangladesh

35 CASE STUDY 3: LIVELIHOOD PROFILES OF FISH FARMERS IN KISHOREGANJ, BANGLADESH A. Background 1. Scope and Purpose 1. This case study was prepared as part of an Asian Development Bank (ADB) special evaluation study on small-scale freshwater rural aquaculture development. The study used primary and secondary data and published information to document the human, social, natural, physical, and financial capital available to the poor involved in the production and consumption of freshwater farmed fish, and to identify various channels through which the poor can benefit, such as through access to livelihood assets, markets and prices, and services and facilities. This case study was designed to highlight the operating environment of small-scale fish farmers in rural Bangladesh and their livelihood profiles.1 2. Relevance 2. Freshwater aquaculture plays an important role in rural livelihoods in Bangladesh. Fish account for 60–80% of the animal protein consumed by the population and also provide essential vitamins, minerals, and fatty acids. Freshwater aquaculture, primarily the farming of carps, provides more than one third of the total fisheries production in Bangladesh. Traditionally, much farmed fish came from ponds constructed as borrow pits, dug to raise the level of land for village homesteads and roads. Most of the country is deltaic and a large portion of the land is inundated in the monsoon season. There has been a dramatic increase in freshwater aquaculture production from 123,800 metric tons (t) in 1986 to 850,000 t in 2002. Of present production, 80% come from the polyculture of Indian, Chinese, common, and other carps in ponds.2 The population of Bangladesh is rapidly increasing and domestic demand for fish is continuing to rise. -

In Recent Years, the Importance of Smallholder Agriculture Has Been

the interventions were not randomized, the potential for selection bias contaminating the results still exists. Using panel data does not completely resolve this issue, but allows us to control for unobserved time–invariant effects. Third, we take advantage of the treatment–comparison design of the original evaluation to undertake three types of comparisons using nearest neighbor matching, comparing (1) early and late adopters of the technology; (2) NGO members with access to the technology and those without access to the technology; and (3) NGO members vs. non–NGO members. Heckman, Ichimura, and Todd (1997, 1998) and Abadie and Imbens (2002) show that under certain conditions on the data, all of which are satisfied in this study, matching estimators provide reliable estimates of program impact. Finally, we use insights drawn from the qualitative work conducted as part of the panel study and earlier work conducted in the study sites to obtain additional perspectives on the role of implementation modalities and collective action. 3. DATA AND SAMPLING 3.1 The initial evaluation sample: an overview of the agricultural technology interventions The initial survey for this study was conducted in 1996–97 by the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI) and Data Analysis and Technical Assistance, Ltd. (DATA) to examine the impacts of improved vegetable and polyculture fish management technologies on household resource allocation, incomes, and nutrition. The initial study also aimed to uncover intrahousehold and gender–differentiated impacts of the new technologies, so extremely detailed information was collected on individuals within households. As mentioned above, households were surveyed in three sites where NGOs and extension programs disseminated the new technologies. -

Key Statistics December 2018 Official Capacity of Actual Population In

Improvement of the Real Situation of Overcrowding in Prisons in Bangladesh (IRSOP) [A joint project of Ministry of Home Affairs (MoHA) and GIZ] Key Statistics December 2018 Official capacity of Actual population in Prisoners in Bangladesh 36,714 Prisons 90,375 As of 30/11/2018 | Source: Prisons Directorate, Bangladesh Achievements by the Paralegal Advisory Services (PAS) from March’09 to December’18 Prisoners assisted Released on Bail, 1,22,175 - Discharged and Acquitted* 20,757 Achievements by the Paralegal Advisory Services (PAS) from December’13 to December’18 PAS Interventions Persons assisted in 6,30,333 Court and Police Station 2,70,124 Prisoners released through project interventions from January’09 to December’18 Released on Bail, Name of the Prison Official Capacity Actual Prisoners Under trial Convicted Discharged & Acquitted* Barishal Central Jail 633 1598 1197 75% 401 25% 815 Bogura District Jail 720 2342 2071 88% 271 12% 2447 Brahmanbaria District Jail 504 1652 1366 83% 286 17% 154 Chandpur District Jail 200 1146 1020 89% 126 11% 657 Chattogram Central Jail 1853 10984 10326 94% 658 6% 965 Cumilla Central Jail 1742 3143 2455 78% 688 22% 976 Dhaka Central Jail 4590 11786 10589 90% 1197 10% 5154 Dinajpur District Jail*** 2000 1546 1241 80% 305 20% 285 Faridpur District Jail 719 1219 1086 89% 133 11% 229 Gaibandha District Jail 200 1068 962 90% 106 10% 87 Gazipur District Jail 207 1398 1310 94% 88 6% 199 Gopalganj District Jail 348 380 316 83% 64 17% 620 Jhenaidah District Jail 200 795 667 84% 128 16% 190 Jashore Central Jail -

Bangladesh Page 1 of 30

2010 Human Rights Report: Bangladesh Page 1 of 30 Home » Under Secretary for Democracy and Global Affairs » Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor » Releases » Human Rights Reports » 2010 Country Reports on Human Rights Practices » South and Central Asia » Bangladesh 2010 Human Rights Report: Bangladesh BUREAU OF DEMOCRACY, HUMAN RIGHTS, AND LABOR 2010 Country Reports on Human Rights Practices April 8, 2011 Bangladesh is a parliamentary democracy of 155 million citizens. Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina Wazed leads the Awami League (AL) alliance, a 14-party coalition with a large majority of parliamentary seats. International and domestic observers considered the 2008 elections to be free and fair, with isolated irregularities and sporadic violence. There were instances in which elements of the security forces acted independently of civilian control. Security forces committed extrajudicial killings and were responsible for custodial deaths, torture, and arbitrary arrest and detention. The failure to investigate fully extrajudicial killings by security forces, including several deaths in custody of alleged criminals detained by the Rapid Action Battalion (RAB), remained a matter of serious concern. Some members of the security forces acted with impunity. Prison conditions at times were life-threatening, lengthy pretrial detention continued to be a problem, and authorities infringed on citizens' privacy rights. An increasingly politicized judiciary exacerbated problems in an already overwhelmed judicial system and constrained access to justice for members of opposition parties. The government limited freedom of speech and of the press, self-censorship continued, and security forces harassed journalists. The government curbed freedom of assembly, and politically motivated violence remained a problem. Official corruption and related impunity continued.