1 LESSON 1 Speech Sounds and Utterance Sanskrit Is Pronounced

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A History of English

A History of the English Language PAGE Proofs © John bEnjamins PublishinG company 2nd proofs PAGE Proofs © John bEnjamins PublishinG company 2nd proofs A History of the English Language Revised edition Elly van Gelderen Arizona State University John Benjamins Publishing Company Amsterdam PAGE/ Philadelphia Proofs © John bEnjamins PublishinG company 2nd proofs TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of 8 the American National Standard for Information Sciences – Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ansi z39.48-1984. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Gelderen, Elly van. A History of the English Language / Elly van Gelderen. -- Revised edition. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. 1. English language--History. 2. English language--History--Problems, exercises, etc. I. Title. PE1075.G453 2014 420.9--dc23 2014000308 isbn 978 90 272 1208 5 (Hb ; alk. paper) isbn 978 90 272 1209 2 (Pb ; alk. paper) isbn 978 90 272 7043 6 (Eb) © 2014 – John Benjamins B.V. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, by print, photoprint, microfilm, or any other means, without written permission from the publisher. John Benjamins Publishing Co. · P.O. Box 36224 · 1020 me Amsterdam · The Netherlandspany John Benjamins North America · PP.O. Boxroofs 27519 · Philadelphia pa 19118-0519G com · usa PAGE Publishin Enjamins © John b 2nd proofs Table of contents Preface to the first edition (2006) ix Preface to the revised edition xii Notes to the user and abbreviations xiv List of tables xvi List of figures xix 1 The English language 1 1. The origins and history of English 1 2. -

“The Role of Specific Grammar for Interpretation in Sanskrit”

Quest Journals Journal of Research in Humanities and Social Science Volume 9 ~ Issue 2 (2021)pp: 107-187 ISSN(Online):2321-9467 www.questjournals.org Research Paper “The Role of Specific Grammar for Interpretation in Sanskrit” Dr. Shibashis Chakraborty Sact-I Depatment of Sanskrit, Panskura Banamali College Wb, India. Abstract: Sanskrit enjoys a place of pride among Indian languages in terms of technology solutions that are available for it within India and abroad. The Indian government through its various agencies has been heavily funding other Indian languages for technology development but the funding for Sanskrit has been slow for a variety of reasons. Despite that, the work in the field has not suffered. The following sections do a survey of the language technology R&D in Sanskrit and other Indian languages. The word `Sanskrit’ means “prepared, pure, refined or prefect”. It was not for nothing that it was called the `devavani’ (language of the Gods). It has an outstanding place in our culture and indeed was recognized as a language of rare sublimity by the whole world. Sanskrit was the language of our philosophers, our scientists, our mathematicians, our poets and playwrights, our grammarians, our jurists, etc. In grammar, Panini and Patanjali (authors of Ashtadhyayi and the Mahabhashya) have no equals in the world; in astronomy and mathematics the works of Aryabhatta, Brahmagupta and Bhaskar opened up new frontiers for mankind, as did the works of Charak and Sushrut in medicine. In philosophy Gautam (founder of the Nyaya system), Ashvaghosha (author of Buddha Charita), Kapila (founder of the Sankhya system), Shankaracharya, Brihaspati, etc., present the widest range of philosophical systems the world has ever seen, from deeply religious to strongly atheistic. -

And *- in Germanic

Archaisms and innovations four interconnected studies on Germanic historical phonology and morphology Hansen, Bjarne Simmelkjær Sandgaard Publication date: 2014 Document version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Citation for published version (APA): Hansen, B. S. S. (2014). Archaisms and innovations: four interconnected studies on Germanic historical phonology and morphology. Det Humanistiske Fakultet, Københavns Universitet. Download date: 01. okt.. 2021 FACULTY OF HUMANITIE S UNIVERSITY OF COPENH AGEN Ph .D. thesis Bjarne Simmelkjær Sandgaard Hansen Archaisms and innovations four interconnected studies on Germanic historical phonology and morphology i Contents LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS ............................................................................................... V 1. Grammatical terms ....................................................................................................................................................... v 2. Linguanyms .................................................................................................................................................................. vi 1. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................. 5 1.1. Archaisms and innovations ....................................................................................................................................... 6 1.2. Aim and purpose of the present thesis .................................................................................................................... -

Indo-European Linguistics: an Introduction Indo-European Linguistics an Introduction

This page intentionally left blank Indo-European Linguistics The Indo-European language family comprises several hun- dred languages and dialects, including most of those spoken in Europe, and south, south-west and central Asia. Spoken by an estimated 3 billion people, it has the largest number of native speakers in the world today. This textbook provides an accessible introduction to the study of the Indo-European proto-language. It clearly sets out the methods for relating the languages to one another, presents an engaging discussion of the current debates and controversies concerning their clas- sification, and offers sample problems and suggestions for how to solve them. Complete with a comprehensive glossary, almost 100 tables in which language data and examples are clearly laid out, suggestions for further reading, discussion points and a range of exercises, this text will be an essential toolkit for all those studying historical linguistics, language typology and the Indo-European proto-language for the first time. james clackson is Senior Lecturer in the Faculty of Classics, University of Cambridge, and is Fellow and Direc- tor of Studies, Jesus College, University of Cambridge. His previous books include The Linguistic Relationship between Armenian and Greek (1994) and Indo-European Word For- mation (co-edited with Birgit Anette Olson, 2004). CAMBRIDGE TEXTBOOKS IN LINGUISTICS General editors: p. austin, j. bresnan, b. comrie, s. crain, w. dressler, c. ewen, r. lass, d. lightfoot, k. rice, i. roberts, s. romaine, n. v. smith Indo-European Linguistics An Introduction In this series: j. allwood, l.-g. anderson and o.¨ dahl Logic in Linguistics d. -

Lesson-10 in Sanskrit, Verbs Are Associated with Ten Different

-------------- Lesson-10 General introduction to the tenses. In Sanskrit, verbs are associated with ten different forms of usage. Of these six relate to the tenses and four relate to moods. We shall examine the usages now. Six tenses are identified as follows. The tenses directly relate to the time associated with the activity specified in the verb, i.e., whether the activity referred to in the verb is taking place now or has it happened already or if it will happen or going to happen etc. Present tense: vtIman kal: There is only one form for the present tense. Past tense: B¥t kal: Past tense has three forms associated with it. 1. Expressing something that had happened sometime in the recent past, typically last few days. 2. Expressing something that might have just happened, typically in the earlier part of the day. 3. Expressing something that had happened in the distant past about which we may not have much or any knowledge. Future tense: B¢vÝyt- kal: Future tense has two forms associated with it. 1. Expressing something that is certainly going to happen. 2. Expressing something that is likely to happen. ------Verb forms not associated with time. There are four forms of the verb which do not relate to any time. These forms are called "moods" in the English language. English grammar specifies three moods which are, Indicative mood, Imperative mood and the Subjunctive mood. In Sanskrit primers one sees a reference to four moods with a slightly different nomenclature. These are, Imperative mood, potential mood, conditional mood and benedictive mood. -

Understanding Verbs Based on Overlapping Verbs Senses

Understanding Verbs based on Overlapping Verbs Senses Kavitha Rajan Language Technologies Research Centre International Institute of Information Technology Hyderabad (IIIT-H) Gachibowli, Hyderabad. 500 032. AP. India. [email protected] Abstract (Schank and Abelson, 1977) were developed from the CD theory. None of the descendant Natural language can be easily understood by theories of CD could focus on the notion of everyone irrespective of their differences in 'primitives' and the idea faded in the subsequent age or region or qualification. The existence works. of a conceptual base that underlies all natural Identification of meaning primitives is an area languages is an accepted claim as pointed out intensely explored and a vast number of theories by Schank in his Conceptual Dependency have been put forward, namely, (PRO: (CD) theory. Inspired by the CD theory and theories in Indian grammatical tradition, we Conceptual semantics (Jackendoff, 1976), propose a new set of meaning primitives in Meaning-text theory (Mel’čuk,1981), Semantic this paper. We claim that this new set of Primes (Wierzbicka, 1996), Conceptual primitives captures the meaning inherent in dependency theory (Schank, 1972) Preference verbs and help in forming an inter-lingual and Semantics (Wilks, 1975) CONTRA: Language of computable ontological classification of Thought (Fodor, 1975)). Through our work, we verbs. We have identified seven primitive put forward a set of seven meaning primitives overlapping verb senses which substantiate and claim that the permutation/combination of our claim. The percentage of coverage of these seven meaning primitives along with these primitives is 100% for all verbs in ontological attributes is sufficient to develop a Sanskrit and Hindi and 3750 verbs in English. -

Contributions to the History of the Deponent Verb in Irish. by J

444 XV1.-CONTRIBUTIONS TO THE HISTORY OF THE DEPONENT VERB IN IRISH. BY J. STRACHAN. [Read at the Meeting of the Philological Society held on Friday, June lrf, 1894.1 THE object of this paper is not to investigate the origin of the T deponent, which Old Irish ahares with Latin, and its relation to the Indo-Germanic verbal system. or to discuss, except inci- dentally so far as they have any bearing on the subject proper, the theories that have been put forward concerning the origin of these forms.' Whether it will ever be possible to get beyond conflicting theories, and to arrive at any certain or even probable account of the genesis of the type, may be reasonably doubted. But, taking the deppnent as it exists in the oldest records of the Irish tongue, it should not be an impossible task to trace, with more or less exactness, its history within the Irish language itself, to follow the old forms in their life and decay, and to search out the starting-point and follow the development of any new types. The degree of precision with which such an investigation can be carried out must depend on the nature of the documents on which it is based. Where there is a continuous series of dated documents, each of which representa faithfully the language of its time, the course of the enquiry will run smoothly enough. In Irish, however, the student does not find himself in this fortunate position. For Old Irish we have trustworthy documents in the Glosses and in fragments of Irish preserved in the oldest manuscripts. -

Reconstructing the Medio-Passive Participle Ofproto-Indo-European

Reconstructing the medio-passive participle ofProto-Indo-European Jesse Storbeck Advisor: Jay Fisher Contents Acknowledgments iii I. Introduction tothe PIE Medio-Passive Participle 1 II. The Laryngeal Hypothesis 9 III. *-mn-/*-men-f*-mon- Alternation 19 IV. The Indo-Iranian Athematic Participle in -iina- 26 V. Balto-Slavic "<mo-, *-men- in the Bigger Picture, and Conclusions on the 33 Medio-Passive Participle References 41 ii Acknowledgments Although this essay bears my name officially, such an effort would have been altogether impossible without the help of a number of talented people, to whom I owe an immense gratitude. I would like to thank Claire Bowern and Larry Horn, as well as my fellow linguistics majors from the class of 2011, who provided me with useful feedback over the course of this past academic year. Additionally, I am grateful to Stanley Insler, who originally suggested this topic to me, and whose expert knowledge and critique I am fortunate to have received. Most of all, my advisor Jay Fisher deserves credit for any scholarly contribution this essay may make. His guidance and support have been crucial throughout every step of the thesis process, and although this essay could be the last academic writing I ever do, the enthusiasm, dedication, and effortwhich Jay brought to the project were beyond the requirements of an undergraduate advisor. He is responsible for the majority of what I know about Indo-European linguistics and is one of the teachers who have truly shaped my education. Finally, I would like to thank all those who ever instructed me in Latin, Greek, Sanskrit, or linguistics. -

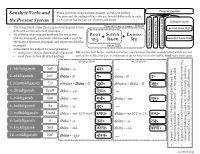

Sanskrit Verbs and the Present System

● ● ● the Present System Present the Verbs Sanskrit and 3. juhotyādigaṇaḥ 3. 2. adādigaṇaḥ 10. curādigaṇaḥ 10. kryādigaṇaḥ 9. tanādigaṇaḥ 8. svādigaṇaḥ 5. divādigaṇaḥ 4. bhvādigaṇaḥ 1. 6. 6. tudādigaṇaḥ 7. 7. rudhādigaṇaḥ ● ● to Somearesubject stems prayogaḥ ( the passive ( these All of of different combinations ten present-stem The kartari prayogaḥ weak strong stem: before all other endings other stem: all before ) stem: before before stem: vikaraṇa karmaṇi prayogaḥ karmaṇi ); a separate separate a ); s are reserved for the active are the sactive reserved for classes paramaipada ekavacana paramaipada ŚnaM ŚyaN Śnu luK Śnā ŚaP ṆiC Ślu vikaraṇa Śa vowel gradation vowel u ( vikaraṇa ) and impersonal ( and impersonal ) gaṇa Each systemEach its has set of own The three are There ) correspond to ten ) correspond s. dhātu dhātu dhātu dhātu dhātu dhātu abhyāsa + dhātu dhātu dhātu stem yaK and the the and : + + + - + + - is used for for used is + + - + ∅ + - - - - - a ya nā o no na aya a - - dhātu - part of the suffix, but give us information about how to use the the suffix. use to about how butgive the ofinformation suffix, us part NB bhāve bhāve - - - - - verbal systems endings strong stem strong - (CV- : In the chart below, capitalized letters are Pāṇinian diacritics ( diacritics are Pāṇinian letters capitalized below, chart : In the +∅ na of the verb are formed differently in each. in formeddifferently verb the are of Root -C) धात : present, aorist, and perfect. and aorist, present, : tenses चोरय॰ क्रीणा॰ तनो॰ 셁णध त स ि餿व्य॰ ज भ픿॰ ए॰ ः ु 餿॰ नो॰ ु हो॰ ु ु + and and Finite verbal form Finite ॰ Suffix ् Stem ि픿करणः moods dhātu dhātu dhātu abhyāsa + dhātu dhātu अङ्गम == == == == . -

Sanskrit Roots of the English Language

SANSKRIT ROOTS OF THE ENGLISH LANGUAGE A-, An-: not, without; << Skt. prefix (or upsarga) a- ( as in a-spasht, unclear, a- drishya, invisible, that which cannot be seen ) ) and an- ( as in an-achar, misbehavior, an-ant, endless, that which has no end, an-abhyas, without practice ) ) Derivatives: a-cephalous; a-cheira, a-chira; a-chondroplasia; a-gnostic, a-gnosia; a-gonic; a-graphia; a-mnesia; a-mnesty; a-moral; a-a- morphous; an-aerobe; an-algesic; an-alphabetic; an-archy; an-arthria; an-emia; an-esthesia; an-hidrosis; an-hydrous; an-ion; an-odyne; an- onym, an-onymous; an-ura; a-pathy; a-phagia; a-phasia, a-phasic; a-pnea; a-rgon; a-sbestos; a-sphyxia; a-sternal; a-stigmatism; a-sylum; a-syndeton; a-theist; a-tom; a-trophy. But Not - amoeba; ascetic; asparagus; astronomy; athlete; Anabaptist; anachronism; anagram. in- as in inin-cessant and un- as in un-developed cognate with a , aann a a and an seen in greek and in and un seen in latin and both gk and latin have taken from skt. a a or an asthenia. deuteranopia; hemianopia; protanopia; tritanopia, anis a a is alpha privative; analphabetic, alphabet, hybrid Abdomen: Ab-do-men, do <Skt. √ √dha, to hold, to support, to create. Abet: < Skt. √ √ bhid , to cleave; L. findere; Gm. bheid Accomplish: Ac-com-pl-ish,, adhi-sam-pur, ac- < ad-, ad- < Skt. Prefix adhi-, above, additional, upon; Skt. Sam, with, together, completely; Skt. √ √ pur, to fill as inin purna, -ish is a verbal suffix. acephalous – – without a head, as an organization, cephal <skt. -

Pircy” an Introduction to Sanskrit : Unit – VI

S;SkÕt &;-;; pircy An Introduction to Sanskrit : Unit VI M. R. Dwarakanath 1ú Xlok (Sloka) i/r Blood Tvcß Skin nmoStu te Vy;s ivx;lbu¸e fuLl;rivNd;ytp]ne] . aiv Sheep an@uhß Ox yen Tvy; &;rttwlpU,R p[Jv;ilto _;nmy p[dIp ô myUr Peacock c$k Sparrow pdCzed (Word decomposition) gO/[ Vulture gTmtß Eagle nm aStu te Vy;s ivX;lbu¸e muDr Beetle &UjNtu Earthworm fuLlöarivNdöa;ytöp]öne] yen Tvy; ao` Flood °imR Wave &;rtötwlöpU,R _;nmy p[dIp ô kNdr Cave ku© Bower aqR (Meaning) mi,k;r Jeweler aySk;r Blacksmith May salutations be ùnm aStuú to you ùteú vi,jß Merchant s*ic Tailor Oh! Vyasa ùVy;sú of vast intellect ùivx;lbu¸eú with eyes ùne]ú like the long ùa;ytú petals b;i/r Deaf mUk Dumb m<@n Decoration m<@l Circle ùp]ú of a fully blossomed ùfuLlú lotus ùarivNdú . The lamp ùp[dIpú of abundant a;tp Sun a;tp] Umbrella knowledge ù_;nmyú was filled ùpU,Rú with a&[k Mica ipTtl Brass the oil ùtwlú of Mahabharata ù&;rtú and itl Seamum m;W Blackgram illumined ùp[Jviltú [by whom] ùyenú by you aBj Lotus aBd Year ùTvy;ú. it Bitter itGm Hot Vy;kr, p[kr,mß (Grammar) ap;y Danger ¯p;y Means Vy;sÚ ivx;lbu¸e and fuLl;rivNd;ytp]ne] are all in the vocative. The verb is in imperative a;rop Attribute apv;d Refutation (prayer.) nm always governs the dative te ùtu>yú. Consider gurve nmÚ deVyw nmÚ kÕ-,;y 2öEú itñNt; (Verbs) : The roots and nmÚ nmSte . -

Indo-European Linguistics: an Introduction Indo-European Linguistics an Introduction

This page intentionally left blank Indo-European Linguistics The Indo-European language family comprises several hun- dred languages and dialects, including most of those spoken in Europe, and south, south-west and central Asia. Spoken by an estimated 3 billion people, it has the largest number of native speakers in the world today. This textbook provides an accessible introduction to the study of the Indo-European proto-language. It clearly sets out the methods for relating the languages to one another, presents an engaging discussion of the current debates and controversies concerning their clas- sification, and offers sample problems and suggestions for how to solve them. Complete with a comprehensive glossary, almost 100 tables in which language data and examples are clearly laid out, suggestions for further reading, discussion points and a range of exercises, this text will be an essential toolkit for all those studying historical linguistics, language typology and the Indo-European proto-language for the first time. james clackson is Senior Lecturer in the Faculty of Classics, University of Cambridge, and is Fellow and Direc- tor of Studies, Jesus College, University of Cambridge. His previous books include The Linguistic Relationship between Armenian and Greek (1994) and Indo-European Word For- mation (co-edited with Birgit Anette Olson, 2004). CAMBRIDGE TEXTBOOKS IN LINGUISTICS General editors: p. austin, j. bresnan, b. comrie, s. crain, w. dressler, c. ewen, r. lass, d. lightfoot, k. rice, i. roberts, s. romaine, n. v. smith Indo-European Linguistics An Introduction In this series: j. allwood, l.-g. anderson and o.¨ dahl Logic in Linguistics d.