Erotic Transgression in Carlos Saura's Tango

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2018 Upland CA

10/9/2018 Control Panel Upland, CA Results Advanced ~ Solo ~ 8 & Under PLACE ROUTINE STUDIO NAME CATEGORY SOLOIST NAME 1ST WHAT'S MY NAME? The Dance Spot Jazz HAYDEN YU 2ND GIMMIE GIMMIE The Dance Spot Character LEAH SANTOS 3RD MY DESTINY The Dance Spot Lyrical LEAH HUTT 4TH BABY MINE The Dance Spot Lyrical LAURYN BAKH 5TH I GOT LOVE Mather Dance Company Open BELLA BLANDING 6TH FIELDS OF GOLD Mather Dance Company Lyrical MYLIE MURILLO Advanced ~ Solo ~ 911 PLACE ROUTINE STUDIO NAME CATEGORY SOLOIST NAME 1ST NICEST THINGS Mather Dance Company Lyrical PEYTON LESSARD 2ND KITRI'S VARIATION The Dance Spot Ballet ALANA ALVARADO 3RD ON MY OWN The Dance Spot Lyrical AVA KO 4TH I'M A LADY Mather Dance Company Jazz ZOEY GARCIA 5TH PAPER SKIN The Dance Spot Lyrical HANNAH NATONIEWSKI 6TH PRAYING The Dance Spot Open ELIANA SWINDLE 7TH EXPENSIVE The Dance Spot Jazz SAMANTHA CHIN 8TH DREAM A LITTLE DREAM The Dance Spot Character SOFIA BORROMEO 9TH FEEL IT STILL Mather Dance Company Jazz ASHLIE MURILLO file:///Users/owner/Downloads/Believe%202018%20Upland%20.htm 1/19 10/9/2018 Control Panel Advanced ~ Solo ~ 1214 PLACE ROUTINE STUDIO NAME CATEGORY SOLOIST NAME 1ST BROTSJO'R The Dance Spot Ballet MALLORY MCKENNA 2ND YOURS The Dance Spot Lyrical BREANNA MEZA 3RD BROWN EYED GIRL The Dance Spot Lyrical HAILEY GUTIERREZ 4TH LOVE SO SOFT The Dance Spot Jazz MARIAH ALVARADO 5TH GIVE IT TO ME RIGHT The Dance Spot Open KRYSTAL SMALL 6TH KEEP BREATHING The Dance Spot Lyrical LEIA ALVARADO 7TH MADNESS Mather Dance Company Contemporary KATIE MURILLO 8TH GOOD TO -

Mow!,'Mum INN Nn

mow!,'mum INN nn %AUNE 20, 1981 $2.75 R1-047-8, a.cec-s_ Q.41.001, 414 i47,>0Z tet`44S;I:47q <r, 4.. SINGLES SLEEPERS ALBUMS COMMODORES.. -LADY (YOU BRING TUBES, -DON'T WANT TO WAIT ANY- POINTER SISTERS, "BLACK & ME UP)" (prod. by Carmichael - eMORE" (prod. by Foster) (writers: WHITE." Once again,thesisters group) (writers: King -Hudson - Tubes -Foster) .Pseudo/ rving multiple lead vocals combine witt- King)(Jobete/Commodores, Foster F-ees/Boone's Tunes, Richard Perry's extra -sensory sonc ASCAP) (3:54). Shimmering BMI) (3 50Fee Waybill and the selection and snappy production :c strings and a drying rhythm sec- ganc harness their craziness long create an LP that's several singles tionbackLionelRichie,Jr.'s enoughtocreate epic drama. deep for many formats. An instant vocal soul. From the upcoming An attrEcti.e piece for AOR-pop. favoriteforsummer'31. Plane' "In the Pocket" LP. Motown 1514. Capitol 5007. P-18 (E!A) (8.98). RONNIE MILSAI3, "(There's) NO GETTIN' SPLIT ENZ, "ONE STEP AHEAD" (prod. YOKO ONO, "SEASON OF GLASS." OVER ME"(prod.byMilsap- byTickle) \rvriter:Finn)(Enz. Released to radio on tape prior to Collins)(writers:Brasfield -Ald- BMI) (2 52. Thick keyboard tex- appearing on disc, Cno's extremel ridge) {Rick Hall, ASCAP) (3:15). turesbuttressNeilFinn'slight persona and specific references tc Milsap is in a pop groove with this tenor or tit's melodic track from her late husband John Lennon have 0irresistible uptempo ballad from the new "Vlaiata- LP. An air of alreadysparkedcontroversyanci hisforthcoming LP.Hissexy, mystery acids to the appeal for discussion that's bound to escaate confident vocal steals the show. -

Vindicating Karma: Jazz and the Black Arts Movement

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 1-1-2007 Vindicating karma: jazz and the Black Arts movement/ W. S. Tkweme University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1 Recommended Citation Tkweme, W. S., "Vindicating karma: jazz and the Black Arts movement/" (2007). Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014. 924. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1/924 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. University of Massachusetts Amherst Library Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2014 https://archive.org/details/vindicatingkarmaOOtkwe This is an authorized facsimile, made from the microfilm master copy of the original dissertation or master thesis published by UMI. The bibliographic information for this thesis is contained in UMTs Dissertation Abstracts database, the only central source for accessing almost every doctoral dissertation accepted in North America since 1861. Dissertation UMI Services From:Pro£vuest COMPANY 300 North Zeeb Road P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106-1346 USA 800.521.0600 734.761.4700 web www.il.proquest.com Printed in 2007 by digital xerographic process on acid-free paper V INDICATING KARMA: JAZZ AND THE BLACK ARTS MOVEMENT A Dissertation Presented by W.S. TKWEME Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2007 W.E.B. -

Stand up Participate Program Year I Evaluation Report

STAND UP PARTICIPATE PROGRAM YEAR I ASIAN MEDIA ACCESS EVALUATION REPORT Prepared by: Rodolfo Gutierrez Eric Armacanqui Yue Zhang November 2015 STAND UP PARTICIPATE (SUP) PROGRAM Year I (09.2014-08.2015) Evaluation Report a Prepared by: HACER with collaboration with Ange Hwang (AMA) HACER HACER’s mission is to provide the Minnesota This report is not copyright protected. Latino community the ability to create and However, HACER must grant permission for the control information about itself in order to affect reproduction of all or part of the enclosed critical institutional decision-making and public material, upon request, information reprinted policy. General support for HACER is provided with permission from other sources, would not by the Center for Urban and Regional Affairs be reproduced. HACER would appreciate (CURA) and Minnesota-based philanthropic acknowledgement, however, as well as two organizations. copies of any material thus reproduced. The content of this report is solely the responsibility of HACER and does not necessarily represent the views of our Executive Director: Rodolfo Gutierrez partners. We are grateful to all who contributed to the making of this report: HACER Thank you to all of those who offered support and 2314 University Ave SE, Apt. 101 expertise for this project, especially Asian Media St. Paul, Minnesota 55114 Access and all SUP program partners (651) 288-1141 www.hacer-mn.org 1 Table of Contents Table of Contents 1 Executive Summary 2 Overview of SUP Program 4 Context Analysis 4 Goal and Objectivities -

The Symbolic Role of Animals in the Plains Indian Sun Dance Elizabeth

17 The Symbolic Role of Animals in the Plains Indian Sun Dance 1 Elizabeth Atwood Lawrence TUFTS UNIVERSITY For many tribes of Plains Indians whose bison-hunting culture flourished during the 18th and 19th centuries, the sun dance was the major communal religious ceremony. Generally held in late spring or early summer, the rite celebrates renewal-the spiritual rebirth of participants and their relatives as well as the regeneration of the living earth with all its components. The sun dance reflects relationships with nature that are characteristic of the Plains ethos, and includes symbolic representations of various animal species, particularly the eagle and the buffalo, that once played vital roles in the lives of the people and are still endowed with sacredness and special powers. The ritual, involving sacrifice and supplication to insure harmony between all living beings, continues to be practiced by many contemporary native Americans. For many tribes of Plains Indians whose buffalo-hunting culture flowered during the 18th and 19th centuries, the sun dance was the major communal religious ceremony. Although details of the event differed in various groups, certain elements were common to most tribal traditions. Generally, the annual ceremony was held in late spring or early summer when people from different bands gathered together again following the dispersal that customarily took place in winter. The sun dance, a ritual of sacrifice performed by virtually all of the High Plains peoples, has been described among the Arapaho, Arikara, Assiniboin, Bannock, Blackfeet, Blood, Cheyenne, Plains Cree, Crow, Gros Ventre, Hidatsa, Kiowa, Mandans, Ojibway, Omaha, Ponca, Sarsi, Shoshone, Sioux (Dakota), and Ute (Spier, 1921, p. -

Reggie Workman Working Man

APRIL 2018—ISSUE 192 YOUR FREE GUIDE TO THE NYC JAZZ SCENE NYCJAZZRECORD.COM REGGIE WORKMAN WORKING MAN JIM JONNY RICHARD EDDIE McNEELY KING WYANDS JEFFERSON Managing Editor: Laurence Donohue-Greene Editorial Director & Production Manager: Andrey Henkin To Contact: The New York City Jazz Record 66 Mt. Airy Road East APRIL 2018—ISSUE 192 Croton-on-Hudson, NY 10520 United States Phone/Fax: 212-568-9628 New York@Night 4 Laurence Donohue-Greene: Interview : JIM Mcneely 6 by ken dryden [email protected] Andrey Henkin: [email protected] Artist Feature : JONNY KING 7 by donald elfman General Inquiries: [email protected] ON The COver : REGGIE WORKMAN 8 by john pietaro Advertising: [email protected] Encore : RICHARD WYANDS by marilyn lester Calendar: 10 [email protected] VOXNews: Lest WE Forget : EDDIE JEFFERSON 10 by ori dagan [email protected] LAbel Spotlight : MINUS ZERO by george grella US Subscription rates: 12 issues, $40 11 Canada Subscription rates: 12 issues, $45 International Subscription rates: 12 issues, $50 For subscription assistance, send check, cash or vOXNEWS 11 by suzanne lorge money order to the address above or email [email protected] Obituaries by andrey henkin Staff Writers 12 David R. Adler, Clifford Allen, Duck Baker, Stuart Broomer, FESTIvAL REPORT Robert Bush, Thomas Conrad, 13 Ken Dryden, Donald Elfman, Phil Freeman, Kurt Gottschalk, Tom Greenland, Anders Griffen, CD REviews 14 Tyran Grillo, Alex Henderson, Robert Iannapollo, Matthew Kassel, Marilyn Lester, Suzanne -

Considering Fraud in a Financial Statement Audit : Practical Guidance for Applying SAS No

University of Mississippi eGrove American Institute of Certified Public Accountants Guides, Handbooks and Manuals (AICPA) Historical Collection 1997 Considering fraud in a financial statement audit : practical guidance for applying SAS no. 82; Michael J. Ramos Anita M. Lyons American Institute of Certified Public Accountants Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/aicpa_guides Part of the Accounting Commons, and the Taxation Commons Recommended Citation Ramos, Michael J.; Lyons, Anita M.; and American Institute of Certified Public Accountants, "Considering fraud in a financial statement audit : practical guidance for applying SAS no. 82;" (1997). Guides, Handbooks and Manuals. 33. https://egrove.olemiss.edu/aicpa_guides/33 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the American Institute of Certified Public Accountants (AICPA) Historical Collection at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Guides, Handbooks and Manuals by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Considering Fraud in a Financial Statement Audit; Practical Guidance lor Applying SAS No. 82 No. SAS Applying lor Guidance Practical Audit; Statement Financial a in Fraud Considering Considering Fraud in a Financial Statement Audit: Practical Guidance for Applying SAS No. 82 AICPA NOTICE TO READERS Considering Fraud in a Financial Statement Audit: Practical Guidance for Applying SAS No. 82 presents the views of the author and others who helped in its development. This publication has not been approved, disapproved, or otherwise acted upon by any senior technical committees of the American Institute of Certified Public Accountants. Therefore, the contents of this publication, including recommendations and suggestions, have no official or authoritative status. -

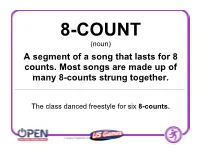

A Segment of a Song That Lasts for 8 Counts. Most Songs Are Made up of Many 8-Counts Strung Together

8-COUNT (noun) A segment of a song that lasts for 8 counts. Most songs are made up of many 8-counts strung together. The class danced freestyle for six 8-counts. BEAT (noun) The regular, rhythmic aspect of music that can be counted and felt in order to coordinate movement. Also, one of the single moments of emphasis in the music that, together, make up the overall beat. Anne moved side to side with the song’s beat as she danced. BOUNCE (verb) To move in a way that imitates an object bouncing (moving quickly back or away from a surface after hitting it). Chloe placed her hands on her knees and bounced them to the rhythm of the song. CALL (noun) A specific instruction to be performed immediately within a dance. The teacher spoke the calls of the dance so the class would know which movements to perform. CALLER (noun) A person who speaks specific instructions during a dance in order to provide guidance to the dancers. Bobby did a great job of being the caller for the dance because he had all the instructions memorized perfectly. CHARGE (verb) To rush forward forcefully. Anthony charged forward, acting like a football player trying to break through the defense. CHOREOGRAPHY (noun) The set and sequence of movements that make up a dance when they are performed. Tasfia remembered all the choreography and performed the dance perfectly. CLOCKWISE (adverb) Movement in the same direction as the way the hands of a clock move around. The class walked clockwise in a circle during the Fjaskern dance. -

Romeo and Juliet | Program Notes

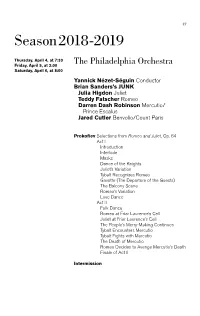

27 Season 2018-2019 Thursday, April 4, at 7:30 Friday, April 5, at 2:00 The Philadelphia Orchestra Saturday, April 6, at 8:00 Yannick Nézet-Séguin Conductor Brian Sanders’s JUNK Julia Higdon Juliet Teddy Fatscher Romeo Darren Dash Robinson Mercutio/ Prince Escalus Jared Cutler Benvolio/Count Paris ProkofievSelections from Romeo and Juliet, Op. 64 Act I Introduction Interlude Masks Dance of the Knights Juliet’s Variation Tybalt Recognizes Romeo Gavotte (The Departure of the Guests) The Balcony Scene Romeo’s Variation Love Dance Act II Folk Dance Romeo at Friar Laurence’s Cell Juliet at Friar Laurence’s Cell The People’s Merry-Making Continues Tybalt Encounters Mercutio Tybalt Fights with Mercutio The Death of Mercutio Romeo Decides to Avenge Mercutio’s Death Finale of Act II Intermission 28 Act III Introduction Farewell Before Parting Juliet Refuses to Marry Paris Juliet Alone Interlude At Friar Laurence’s Cell Interlude Juliet Alone Dance of the Girls with Lilies At Juliet’s Bedside Act IV Juliet’s Funeral The Death of Juliet Additional cast: Aaron Mitchell Frank Leone Kyle Yackoski Kelly Trevlyn Amelia Estrada Briannon Holstein Jess Adams This program runs approximately 2 hours, 5 minutes. These concerts are part of the Fred J. Cooper Memorial Organ Experience, supported through a generous grant from the Wyncote Foundation. These concerts are made possible, in part, through income from the Allison Vulgamore Legacy Endowment Fund. The April 4 concert is sponsored by Sandra and David Marshall. The April 5 concert is sponsored by Gail Ehrlich in memory of Dr. George E. -

Classic Case Studies in Accounting Fraud”

“Classic Case Studies in Accounting Fraud” A thesis submitted to the Miami University Honors Program in partial fulfillment of the requirements for University Honors. by Justin Matthew Mock May 2004 Oxford, Ohio ABSTRACT “Classic Case Studies in Accounting Fraud” by Justin Matthew Mock Over the past several years, accounting fraud has dominated the headlines of mainstream news. While these recent cases all involve sums of money far in excess of any before, accounting fraud is certainly not a new phenomenon. Since the early days on Wall Street, fraud has consistently fooled the markets, investors, and auditors alike. In this thesis, an analysis of several cases of accounting fraud is conducted with background information, fraud logistics, and accounting and auditing violations all subject to study. This paper discusses specific cases of fraud and presents the issues that have been and must continue to be addressed as companies push the envelope of acceptable accounting standards. The discussion and findings demonstrate the ever-present potential for fraud in a variety of accounts, companies, industries, and time periods, while also having a powerful influence on an auditor’s work and preconceptions going forward. iii iv “Classic Case Studies in Accounting Fraud” by Justin Matthew Mock Approved by: _________________________, Advisor Dr. Phil Cottell _________________________, Reader Dr. Larry Rankin _________________________, Reader Mr. Jeffrey Vorholt Accepted by: __________________________, Director, University Honors Program v vi ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS “Classic Case Studies in Accounting Fraud” was completed under the direction of the Miami University Honors Program. The Honors Program provided financial support essential to the project’s research and successful completion. -

THE COLLECTED POEMS of HENRIK IBSEN Translated by John Northam

1 THE COLLECTED POEMS OF HENRIK IBSEN Translated by John Northam 2 PREFACE With the exception of a relatively small number of pieces, Ibsen’s copious output as a poet has been little regarded, even in Norway. The English-reading public has been denied access to the whole corpus. That is regrettable, because in it can be traced interesting developments, in style, material and ideas related to the later prose works, and there are several poems, witty, moving, thought provoking, that are attractive in their own right. The earliest poems, written in Grimstad, where Ibsen worked as an assistant to the local apothecary, are what one would expect of a novice. Resignation, Doubt and Hope, Moonlight Voyage on the Sea are, as their titles suggest, exercises in the conventional, introverted melancholy of the unrecognised young poet. Moonlight Mood, To the Star express a yearning for the typically ethereal, unattainable beloved. In The Giant Oak and To Hungary Ibsen exhorts Norway and Hungary to resist the actual and immediate threat of Prussian aggression, but does so in the entirely conventional imagery of the heroic Viking past. From early on, however, signs begin to appear of a more personal and immediate engagement with real life. There is, for instance, a telling juxtaposition of two poems, each of them inspired by a female visitation. It is Over is undeviatingly an exercise in romantic glamour: the poet, wandering by moonlight mid the ruins of a great palace, is visited by the wraith of the noble lady once its occupant; whereupon the ruins are restored to their old splendour. -

Wavelength Midlo Center for New Orleans Studies

University of New Orleans ScholarWorks@UNO Wavelength Midlo Center for New Orleans Studies 1-1981 Wavelength (January 1981) Connie Atkinson University of New Orleans Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uno.edu/wavelength Recommended Citation Wavelength (January 1981) 3 https://scholarworks.uno.edu/wavelength/3 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Midlo Center for New Orleans Studies at ScholarWorks@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Wavelength by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. fl\ 1 1.) -z/1 I What Makes THE COLD So Hot? JANUARY 1981 VOLUME 1 NUMBER 3 by The Editors of .Rolling Stone Magazine From The Wall Street Journal of Rock comes THE ROLLING STONE MAG- AZINE ROCK REVUE .. the idea behind the most exciti ng concepr in rock radio si nce the album-cut format. THE ROLLING STONE MAGAZINE ROCK REVUE is rock ·n roll news at its best-as onlv the bible of the Rock Music industry could bring to your listeners. Featuring behind-the-scene stories of concert tours. recording sessions. rock ·n roll parties. movies. benefits. record reviews. interviews. the latest album music ... everything happening in Rock today. and tomorrow. Listen for it Weeknights fm at 9:50p.m . B? 10:50p .m . Requests: 260-1100 100 Concert Info:260- WRNO JANUARY 1981 VOLUME 1 NUMBER 3 Features What Makes The Cold So Hot?______ ___,._ 6 Patrice Fisher _ 10 Cajun Bandstands 12 Salt Creek Band 14 Departments January_ 4 Jazz ____________________________19 Rare Records _20 Pop ___21 ~~ n Rock _ 3 Reviews _.25 Open 2 p.m.