Considering Fraud in a Financial Statement Audit : Practical Guidance for Applying SAS No

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2018 Upland CA

10/9/2018 Control Panel Upland, CA Results Advanced ~ Solo ~ 8 & Under PLACE ROUTINE STUDIO NAME CATEGORY SOLOIST NAME 1ST WHAT'S MY NAME? The Dance Spot Jazz HAYDEN YU 2ND GIMMIE GIMMIE The Dance Spot Character LEAH SANTOS 3RD MY DESTINY The Dance Spot Lyrical LEAH HUTT 4TH BABY MINE The Dance Spot Lyrical LAURYN BAKH 5TH I GOT LOVE Mather Dance Company Open BELLA BLANDING 6TH FIELDS OF GOLD Mather Dance Company Lyrical MYLIE MURILLO Advanced ~ Solo ~ 911 PLACE ROUTINE STUDIO NAME CATEGORY SOLOIST NAME 1ST NICEST THINGS Mather Dance Company Lyrical PEYTON LESSARD 2ND KITRI'S VARIATION The Dance Spot Ballet ALANA ALVARADO 3RD ON MY OWN The Dance Spot Lyrical AVA KO 4TH I'M A LADY Mather Dance Company Jazz ZOEY GARCIA 5TH PAPER SKIN The Dance Spot Lyrical HANNAH NATONIEWSKI 6TH PRAYING The Dance Spot Open ELIANA SWINDLE 7TH EXPENSIVE The Dance Spot Jazz SAMANTHA CHIN 8TH DREAM A LITTLE DREAM The Dance Spot Character SOFIA BORROMEO 9TH FEEL IT STILL Mather Dance Company Jazz ASHLIE MURILLO file:///Users/owner/Downloads/Believe%202018%20Upland%20.htm 1/19 10/9/2018 Control Panel Advanced ~ Solo ~ 1214 PLACE ROUTINE STUDIO NAME CATEGORY SOLOIST NAME 1ST BROTSJO'R The Dance Spot Ballet MALLORY MCKENNA 2ND YOURS The Dance Spot Lyrical BREANNA MEZA 3RD BROWN EYED GIRL The Dance Spot Lyrical HAILEY GUTIERREZ 4TH LOVE SO SOFT The Dance Spot Jazz MARIAH ALVARADO 5TH GIVE IT TO ME RIGHT The Dance Spot Open KRYSTAL SMALL 6TH KEEP BREATHING The Dance Spot Lyrical LEIA ALVARADO 7TH MADNESS Mather Dance Company Contemporary KATIE MURILLO 8TH GOOD TO -

Stand up Participate Program Year I Evaluation Report

STAND UP PARTICIPATE PROGRAM YEAR I ASIAN MEDIA ACCESS EVALUATION REPORT Prepared by: Rodolfo Gutierrez Eric Armacanqui Yue Zhang November 2015 STAND UP PARTICIPATE (SUP) PROGRAM Year I (09.2014-08.2015) Evaluation Report a Prepared by: HACER with collaboration with Ange Hwang (AMA) HACER HACER’s mission is to provide the Minnesota This report is not copyright protected. Latino community the ability to create and However, HACER must grant permission for the control information about itself in order to affect reproduction of all or part of the enclosed critical institutional decision-making and public material, upon request, information reprinted policy. General support for HACER is provided with permission from other sources, would not by the Center for Urban and Regional Affairs be reproduced. HACER would appreciate (CURA) and Minnesota-based philanthropic acknowledgement, however, as well as two organizations. copies of any material thus reproduced. The content of this report is solely the responsibility of HACER and does not necessarily represent the views of our Executive Director: Rodolfo Gutierrez partners. We are grateful to all who contributed to the making of this report: HACER Thank you to all of those who offered support and 2314 University Ave SE, Apt. 101 expertise for this project, especially Asian Media St. Paul, Minnesota 55114 Access and all SUP program partners (651) 288-1141 www.hacer-mn.org 1 Table of Contents Table of Contents 1 Executive Summary 2 Overview of SUP Program 4 Context Analysis 4 Goal and Objectivities -

The Symbolic Role of Animals in the Plains Indian Sun Dance Elizabeth

17 The Symbolic Role of Animals in the Plains Indian Sun Dance 1 Elizabeth Atwood Lawrence TUFTS UNIVERSITY For many tribes of Plains Indians whose bison-hunting culture flourished during the 18th and 19th centuries, the sun dance was the major communal religious ceremony. Generally held in late spring or early summer, the rite celebrates renewal-the spiritual rebirth of participants and their relatives as well as the regeneration of the living earth with all its components. The sun dance reflects relationships with nature that are characteristic of the Plains ethos, and includes symbolic representations of various animal species, particularly the eagle and the buffalo, that once played vital roles in the lives of the people and are still endowed with sacredness and special powers. The ritual, involving sacrifice and supplication to insure harmony between all living beings, continues to be practiced by many contemporary native Americans. For many tribes of Plains Indians whose buffalo-hunting culture flowered during the 18th and 19th centuries, the sun dance was the major communal religious ceremony. Although details of the event differed in various groups, certain elements were common to most tribal traditions. Generally, the annual ceremony was held in late spring or early summer when people from different bands gathered together again following the dispersal that customarily took place in winter. The sun dance, a ritual of sacrifice performed by virtually all of the High Plains peoples, has been described among the Arapaho, Arikara, Assiniboin, Bannock, Blackfeet, Blood, Cheyenne, Plains Cree, Crow, Gros Ventre, Hidatsa, Kiowa, Mandans, Ojibway, Omaha, Ponca, Sarsi, Shoshone, Sioux (Dakota), and Ute (Spier, 1921, p. -

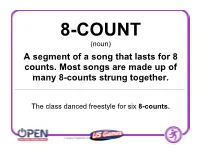

A Segment of a Song That Lasts for 8 Counts. Most Songs Are Made up of Many 8-Counts Strung Together

8-COUNT (noun) A segment of a song that lasts for 8 counts. Most songs are made up of many 8-counts strung together. The class danced freestyle for six 8-counts. BEAT (noun) The regular, rhythmic aspect of music that can be counted and felt in order to coordinate movement. Also, one of the single moments of emphasis in the music that, together, make up the overall beat. Anne moved side to side with the song’s beat as she danced. BOUNCE (verb) To move in a way that imitates an object bouncing (moving quickly back or away from a surface after hitting it). Chloe placed her hands on her knees and bounced them to the rhythm of the song. CALL (noun) A specific instruction to be performed immediately within a dance. The teacher spoke the calls of the dance so the class would know which movements to perform. CALLER (noun) A person who speaks specific instructions during a dance in order to provide guidance to the dancers. Bobby did a great job of being the caller for the dance because he had all the instructions memorized perfectly. CHARGE (verb) To rush forward forcefully. Anthony charged forward, acting like a football player trying to break through the defense. CHOREOGRAPHY (noun) The set and sequence of movements that make up a dance when they are performed. Tasfia remembered all the choreography and performed the dance perfectly. CLOCKWISE (adverb) Movement in the same direction as the way the hands of a clock move around. The class walked clockwise in a circle during the Fjaskern dance. -

Classic Case Studies in Accounting Fraud”

“Classic Case Studies in Accounting Fraud” A thesis submitted to the Miami University Honors Program in partial fulfillment of the requirements for University Honors. by Justin Matthew Mock May 2004 Oxford, Ohio ABSTRACT “Classic Case Studies in Accounting Fraud” by Justin Matthew Mock Over the past several years, accounting fraud has dominated the headlines of mainstream news. While these recent cases all involve sums of money far in excess of any before, accounting fraud is certainly not a new phenomenon. Since the early days on Wall Street, fraud has consistently fooled the markets, investors, and auditors alike. In this thesis, an analysis of several cases of accounting fraud is conducted with background information, fraud logistics, and accounting and auditing violations all subject to study. This paper discusses specific cases of fraud and presents the issues that have been and must continue to be addressed as companies push the envelope of acceptable accounting standards. The discussion and findings demonstrate the ever-present potential for fraud in a variety of accounts, companies, industries, and time periods, while also having a powerful influence on an auditor’s work and preconceptions going forward. iii iv “Classic Case Studies in Accounting Fraud” by Justin Matthew Mock Approved by: _________________________, Advisor Dr. Phil Cottell _________________________, Reader Dr. Larry Rankin _________________________, Reader Mr. Jeffrey Vorholt Accepted by: __________________________, Director, University Honors Program v vi ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS “Classic Case Studies in Accounting Fraud” was completed under the direction of the Miami University Honors Program. The Honors Program provided financial support essential to the project’s research and successful completion. -

THE COLLECTED POEMS of HENRIK IBSEN Translated by John Northam

1 THE COLLECTED POEMS OF HENRIK IBSEN Translated by John Northam 2 PREFACE With the exception of a relatively small number of pieces, Ibsen’s copious output as a poet has been little regarded, even in Norway. The English-reading public has been denied access to the whole corpus. That is regrettable, because in it can be traced interesting developments, in style, material and ideas related to the later prose works, and there are several poems, witty, moving, thought provoking, that are attractive in their own right. The earliest poems, written in Grimstad, where Ibsen worked as an assistant to the local apothecary, are what one would expect of a novice. Resignation, Doubt and Hope, Moonlight Voyage on the Sea are, as their titles suggest, exercises in the conventional, introverted melancholy of the unrecognised young poet. Moonlight Mood, To the Star express a yearning for the typically ethereal, unattainable beloved. In The Giant Oak and To Hungary Ibsen exhorts Norway and Hungary to resist the actual and immediate threat of Prussian aggression, but does so in the entirely conventional imagery of the heroic Viking past. From early on, however, signs begin to appear of a more personal and immediate engagement with real life. There is, for instance, a telling juxtaposition of two poems, each of them inspired by a female visitation. It is Over is undeviatingly an exercise in romantic glamour: the poet, wandering by moonlight mid the ruins of a great palace, is visited by the wraith of the noble lady once its occupant; whereupon the ruins are restored to their old splendour. -

Erotic Transgression in Carlos Saura's Tango

EURAMERICA Vol. 50, No. 1 (March 2020), 79-135 DOI: 10.7015/JEAS.202003_50(1).0003 http://euramerica.org Erotic Transgression in Carlos Saura’s Tango* TP PT P P Yuh-Yi Tan Center for General Education, National Taipei University of Business No. 321, Sec. 1, Jinan Rd., Taipei 10051, Taiwan E-mail: [email protected] Abstract Carlos Saura’s musical film Tango, an audio-visual poem, is patterned upon the discourse of the Argentine tango in its pursuit of cultural otherness. The film elucidates the mid-life crisis of writer/director Mario reframed in an erotic site wherein his masculinity is challenged, distressed, and resurrected. With a playful metanarrative attached to love romance and dance spectacle, Tango crosses between the genres of melodrama and dark fantasy to conjure up the weakness of masculine hegemony threatened by murder and sexuality. A genealogy of the erotic via Georges Bataille’s taboo-transgression relation substantiates the perception that Mario’s self is being reconstituted in an erotic and sacrificial rite transpiring on the architectural terrain of tango dance and © Institute of European and American Studies, Academia Sinica Received March 14, 2019; accepted November 4, 2019; last revised December 2, 2019 Proofreaders: Wen-Chi Chang, Chih-Wei Wu, Chia-Chi Tseng * The authoress would like to show her gratitude for the three anonymous reviewers for their insightful suggestions. This article has been sponsored by Ministry of Science and Technology under the name of “Erotic Tango” project (NSC 101- 2410-H-141-011). 80 EURAMERICA musical scenes. In these mise-en-scènes, the subject separates his “other” self from a patriarchal figure with the help of revisionist femme fatales Elena and Laura, as well as with his competitors, Ernesto and Angelo, who challenge him to avoid a living death. -

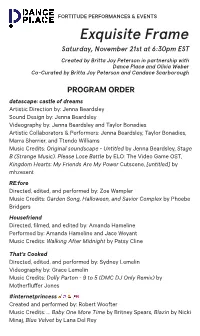

Exquisite Frame

FORTITUDE PERFORMANCES & EVENTS Exquisite Frame Saturday, November 21st at 6:30pm EST Created by Britta Joy Peterson in partnership with Dance Place and Olivia Weber Co-Curated by Britta Joy Peterson and Candace Scarborough PROGRAM ORDER datascape: castle of dreams Artistic Direction by: Jenna Beardsley Sound Design by: Jenna Beardsley Videography by: Jenna Beardsley and Taylor Bonadies Artistic Collaborators & Performers: Jenna Beardsley, Taylor Bonadies, Marra Sherrier, and Ttendo Williams Music Credits: Original soundscape - Untitled by Jenna Beardsley, Stage B (Strange Music). Please Lose Battle by ELO: The Video Game OST, Kingdom Hearts: My Friends Are My Power Cutscene, [untitled] by mhzesent RE:fore Directed, edited, and performed by: Zoe Wampler Music Credits: Garden Song, Halloween, and Savior Complex by Phoebe Bridgers Housefriend Directed, filmed, and edited by: Amanda Hameline Performed by: Amanda Hameline and Jace Weyant Music Credits: Walking After Midnight by Patsy Cline That’s Cooked Directed, edited, and performed by: Sydney Lemelin Videography by: Grace Lemelin Music Credits: Dolly Parton - 9 to 5 (DMC DJ Only Remix) by Motherfluffer Jones #internetprincess Created and performed by: Robert Woofter Music Credits: … Baby One More Time by Britney Spears, Blazin by Nicki Minaj, Blue Velvet by Lana Del Rey ARTIST BIOGRAPHIES Originally from the suburbs of Washington D.C., JENNA BEARDSLEY (they/ them), datascape: castle of dreams, is a movement and multimedia artist currently based in Richmond, Virginia. Jenna graduated with honors in May 2020, holding a Bachelors degree of Fine Arts from Virginia Commonwealth University (VCU). Jenna has studied from artists such as Scott Putman, Johnnie Cruise Mercer, Kristopher K.Q. -

Grand Rapids, MI

Showbiz Grand Rapids 2021 Overalls Rank Routine Dancer Studio Sapphire Mini Small Group 1 Minie's Yoohoo Fusion Center for Dance Sapphire Petite Solo 1 Happy Boys Girls Fiona Soukup Kathy’s Dance Co 2 Me Too Everly Rose Dance Dimensions Sapphire Petite Duet/Trio 1 Come See About Me Kathy’s Dance Co 2 Something To Dance For Dance Dimensions 3 Some Days Studio Dance Sapphire Petite Small Group 1 Coast 2 Coast Kathy’s Dance Co 2 Rockin' Robin Studio Dance 3 Think Fusion Center for Dance 4 You Are My Sunshine Dance Dimensions 5 Sassy Divas Dance Dimensions 6 Walking On Sunshine Studio Dance 7 Just Sing Center Stage Dance Academy Sapphire Petite Large Group 1 Somewhere Over The Rainbow Kathy’s Dance Co 2 Move It Like This Kathy’s Dance Co 3 5678 Dance Dimensions 4 Friend Like Me Dance Dimensions 5 Rain On Me Dance Dimensions 6 Mean Girls Dance Dimensions Sapphire Pre-Junior Solo 1 Flashlight Sabrina Siegel Dance Dimensions 2 Tribe Mikayla Sandner Studio Dance 3 Girls Just Wanna Have Fun Keira Prokopy Dance Dimensions 4 I Wanna Dance With Somebody Sophia Jones Dance Dimensions 5 No Excuses Curdreaah Parker Dance Dimensions Showbiz Grand Rapids 2021 Overalls Rank Routine Dancer Studio 6 I Will Wait Lena Schillim Dance Dimensions 7 All I Want Lilly Anderson Dance Dimensions 8 The Wizards And I Braylon Magoon Dance Dimensions 9 The Climb Maylee Ewing Dance Dimensions Sapphire Junior Solo 1 Candlelight Carlie Bernhardt Dance Dimensions 2 Head Above Water Savannah Rose Dance Dimensions 3 The Greatest Sage Saunders Dance Dimensions 4 Nobody Lila Redder -

Accounting for Violence: How to Increase Safety and Break Our Failed Reliance on Mass Incarceration

Accounting for Violence: How to Increase Safety and Break Our Failed Reliance on Mass Incarceration Danielle Sered Accounting for Violence: How to Increase Safety and Break Our Failed Reliance on Mass Incarceration 1 About Common Justice Common Justice develops and advances solutions to violence that transform the lives of those harmed and foster racial equity without relying on incarceration. Locally, we operate the first alternative to incarceration and victim service program in the United States to focus on violent felonies in the adult courts. Nationally, we leverage the lessons from our direct service to transform the justice system through partnerships, advocacy, and elevating the experience and power of those most impacted. Rigorous and hopeful, we build practical strategies to hold people accountable for harm, break cycles of violence, and secure safety, healing, and justice for survivors and their communities. Suggested Citation Danielle Sered. Accounting for Violence: How to Increase Safety and Break Our Failed Reliance on Mass Incarceration. New York: Vera Institute of Justice, 2017. Accounting for Violence: How to Increase Safety and Break Our Failed Reliance on Mass Incarceration 2 a Contents 4 Confronting the question of violence 7 A new vision for justice 9 Principle 1: Responses should be survivor-centered 17 Principle 2: Responses should be accountability-based 22 Principle 3: Responses should be safety-driven 26 Principle 4: Responses should be racially equitable 29 The vision in practice 30 Conclusion 31 Endnotes Accounting for Violence: How to Increase Safety and Break Our Failed Reliance on Mass Incarceration 3 Confronting the question of violence he United States faces two distinct but interconnected challenges: violence and mass incarceration. -

U.S. Attorneys' Bulletin Vol 50 No 02, Fraud in the Corporate Context

Fraud in the M arch 20 02 Corporate Context Volume 50 Num ber 2 In This Issue United States Department of Justice Executive Office for United States Attorneys The FBI Criminal Undercover Operations Review Committee ......... 1 Office of Legal Education Washingt on, DC By Joshua R. Hochberg 20535 Investigating Accounting Frauds ............................ 3 Kenneth L. Wainstein Director By Dav id L. A nderson and J oseph W . St . Denis Contributors’ opinions and Prime Bank/High Yield Investment Schemes ................... 10 statements should not be considered an endorsement By Joel E. Leising and Michael McGarry by EOUSA for any policy, program, or service Prosecuting Corporations: The Federal Principles and Corporate Compliance The United St ates At torney s’ Programs ........................................... 19 Bulletin is published pursuant to 28 CFR § 0.2 2(b) By Philip Urofsky The United St ates At torney s’ Ex Parte Contacts with Corporate Employees .................. 26 Bulletin is published bi- monthly by the Executive By Edw ard I. Hagen Off ice fo r Unit ed Stat es At torn eys, Of fic e of Legal Navigating the Evolving Landscape of M edical Record Privacy ....... 30 Education, 1620 Pendleton Street, Columbia, South By Ian C. Sm ith DeW aal Carolina 2 920 1. Perio dical postage paid at Washington, D.C. Postmaster: Send Primer for Using Sentencing Guidelines Enhancement for Identity Theft- address changes to Editor, Related Conduct ................................ 39 United St ates At torney s’ Bulleti n, Of fic e of Legal Education, 1620 Pendleton By Paula J. Desio and Donald A . Purdy, J r. Street, Columbia, South Carolina 29201 Managing Editor Jim Do novan Assistant Editor Nancy Bow man Law Clerk Ginny Nis sen Intern et A ddress ww w.usdoj.gov/usao/ eousa/foia/foiamanuals.html Send article submissions to Managin g Editor , Unit ed States Attorneys’ Bulletin, National Advocacy Center Office of Legal Education 162 0 Pendlet on Str eet Columbia, SC 29201 The FBI Criminal Undercover Operations Review Committee Joshua R. -

Sweet 16 Hot List

Sweet 16 Hot List Song Artist Happy Pharrell Best Day of My Life American Authors Run Run Run Talk Dirty to Me Jason Derulo Timber Pitbull Demons & Radioactive Imagine Dragons Dark Horse Katy Perry Find You Zedd Pumping Blood NoNoNo Animals Martin Garrix Empire State of Mind Jay Z The Monster Eminem Blurred Lines We found Love Rihanna/Calvin Love Me Again John Newman Dare You Hardwell Don't Say Goodnight Hot Chella Rae All Night Icona Pop Wild Heart The Vamps Tennis Court & Royals Lorde Songs by Coldplay Counting Stars One Republic Get Lucky Daft punk Sexy Back Justin Timberland Ain't it Fun Paramore City of Angels 30 Seconds Walking on a Dream Empire of the Sun If I loose Myself One Republic (w/Allesso mix) Every Teardrop is a Waterfall mix Coldplay & Swedish Mafia Hey Ho The Lumineers Turbulence Laidback Luke Steve Aoki Lil Jon Pursuit of Happiness Steve Aoki Heads will roll Yeah yeah yeah's A-trak remix Mercy Kanye West Crazy in love Beyonce and Jay-z Pop that Rick Ross, Lil Wayne, Drake Reason Nervo & Hook N Sling All night longer Sammy Adams Timber Ke$ha, Pitbull Alive Krewella Teach me how to dougie Cali Swag District Aye ladies Travis Porter #GETITRIGHT Miley Cyrus We can't stop Miley Cyrus Lip gloss Lil mama Turn down for what Laidback Luke Get low Lil Jon Shots LMFAO We found love Rihanna Hypnotize Biggie Smalls Scream and Shout Cupid Shuffle Wobble Hips Don’t Lie Sexy and I know it International Love Whistle Best Love Song Chris Brown Single Ladies Danza Kuduro Can’t Hold Us Kiss You One direction Don’t You worry Child Don’t