Erik Satie's Letters Nigel Wilkins

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nicolas Horvath Erik Satie (1866-1925) Intégrale De La Musique Pour Piano • 2 Nouvelle Édition Salabert

SATIE INTÉGRALE DE LA MUSIQUE POUR PIANO • 2 NOUVELLE ÉDITION SALABERT LE FILS DES ÉTOILES NICOLAS HORVATH ERIK SATIE (1866-1925) INTÉGRALE DE LA MUSIQUE POUR PIANO • 2 NOUVELLE ÉDITION SALABERT LE FILS DES ÉTOILES NICOLAS HORVATH, Piano Numéro de catalogue : GP762 Date d’enregistrement : 10 décembre 2014 Lieu d’enregistrement : Villa Bossi, Bodio, Italie Publishers: Durand/Salabert/Eschig 2016 Edition Piano : Érard de Cosima Wagner, modèle 55613, année 1881 Producteur et Éditeur : Alexis Guerbas (Les Rouages) Ingénieur du son : Ermanno De Stefani Rédaction du livret : Robert Orledge Traduction française : Nicolas Horvath Photographies de l’artiste : Laszlo Horvath Portrait du compositeur : Paul Signac, (c. 1890, Crayon Conté on paper) © Musée d’Orsay, Paris Cover Art: Sigrid Osa L’artiste tient à remercier sincèrement Ornella Volta et la Fondation Erik Satie. 2 LE FILS DES ÉTOILES (?1891) * 73:56 1 Prélude de l’Acte 1 – La Vocation 03:53 2 Autre musique pour le Premier Acte 21:28 3 Prélude de l’Acte 2 – L’Initiation 03:25 4 Autre musique pour le Deuxième Acte 20:59 5 Prélude de l’Acte 3 – L’Incantation 05:10 6 Autre musique pour le Troisième Acte 18:38 7 FÊTE DONNÉE PAR DES CHEVALIERS NORMANDS EN L’HONNEUR D’UNE JEUNE DEMOISELLE (XIe SIÈCLE) (1892) 03:08 * PREMIER ENREGISTREMENT MONDIAL DURÉE TOTALE: 77:10 DE LA VERSION RÉVISÉE PAR ROBERT ORLEDGE 3 ERIK SATIE (1866-1925) INTÉGRALE DE LA MUSIQUE POUR PIANO • NOUVELLE ÉDITION SALABERT À PROPOS DE NICOLAS HORVATH ET DE LA NOUVELLE ÉDITION SALABERT DES « ŒUVRES POUR PIANO » DE SATIE. En 2014, j’ai été contacté (en tant que professeur de musicologie spécialiste de Satie) par Nicolas Horvath, un jeune pianiste français de renommée internationale, à propos d’un projet d’enregistrement des œuvres complètes pour piano. -

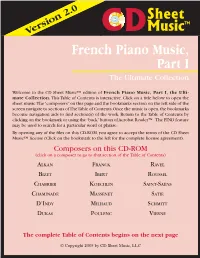

Table of Contents Is Interactive

Sheet TM Version 2.0 CDMusic 1 French Piano Music, Part I The Ultimate Collection Welcome to the CD Sheet Music™ edition of French Piano Music, Part I, the Ulti- mate Collection. This Table of Contents is interactive. Click on a title below to open the sheet music. The “composers” on this page and the bookmarks section on the left side of the screen navigate to sections of The Table of Contents.Once the music is open, the bookmarks become navigation aids to find section(s) of the work. Return to the Table of Contents by clicking on the bookmark or using the “back” button of Acrobat Reader™. The FIND feature may be used to search for a particular word or phrase. By opening any of the files on this CD-ROM, you agree to accept the terms of the CD Sheet Music™ license (Click on the bookmark to the left for the complete license agreement). Composers on this CD-ROM (click on a composer to go to that section of the Table of Contents) ALKAN FRANCK RAVEL BIZET IBERT ROUSSEL CHABRIER KOECHLIN SAINT-SAËNS CHAMINADE MASSENET SATIE D’INDY MILHAUD SCHMITT DUKAS POULENC VIERNE The complete Table of Contents begins on the next page © Copyright 2005 by CD Sheet Music, LLC Sheet TM Version 2.0 CDMusic 2 VALENTIN ALKAN IV. La Bohémienne Saltarelle, Op. 23 V. Les Confidences Prélude in B Major, from 25 Préludes, VI. Le Retour Op. 31, No. 3 Variations Chromatiques de concert Symphony, from 12 Études Nocturne in D Major I. Allegro, Op. 39, No. -

Open Boerner Thesis.Pdf

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School School of Music INTERMEDIAL AND AESTHETIC INFLUENCES ON ERIK SATIE’S LATE COMPOSITIONAL PRACTICES A Thesis in Music Theory by Michael S. Boerner © 2013 Michael S. Boerner Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts May 2013 The thesis of Michael S. Boerner was reviewed and approved* by the following: Taylor A. Greer Associate Professor of Music Thesis Advisor Maureen A. Carr Distinguished Professor of Music Marica S. Tacconi Professor of Musicology Assistant Director for Research and Graduate Studies *Signatures are on file in the Graduate School. ii ABSTRACT Artistic works involving a variety of mediums tend to be approached and analyzed from a single artistic viewpoint, failing to consider the interactions of the different mediums that define the work as a whole. The creative process is influenced by the types of mediums involved, individuals participating in the collaboration, and the overall aesthetic climate of the period. Erik Satie (1866-1925) created numerous intermedial works in the last decade of his life where the medium impacted the compositional practices contained within his music. Satie was also tangentially involved in a number of artistic and aesthetic movements, such as Cubism, Dadaism, and early Surrealism, which influenced his integration. His personal relations and collaborations with prominent artists of these movements, such as Francis Picabia, André Breton, and Pablo Picasso. The works investigated in this thesis highlight Satie’s consideration of extramusical influences and include Sports et divertissements (1923), Parade (1917), Relâche (1924), and Cinéma: Entr’acte (1924). Two additional pieces composed by the Dada artist Georges Ribemont-Dessaignes (1884-1974) will also be examined as a point of comparison with Satie’s works. -

SUMMERGARDEN Program Is Dedicated to the Music of Erik Satie (1866-1925) in Celebration of the 125Th Anniversary of His Birth

PROGRAM Summergarden For 1991, The Museum of Modern Art's SUMMERGARDEN program is dedicated to the music of Erik Satie (1866-1925) in celebration of the 125th anniversary of his birth. Under the artistic direction of Paul Zukofsky, the 1991 concert series marks the fifth collaboration between the Museum and The Juilliard School. SUMMERGARDEN, free weekend evenings from July 6 to September 1, 6:00 - 10:00 p.m., is made possible in part by NYNEX Corporation. Concerts, beginning at 7:30 p.m., are performed by young artists and recent graduates of The Juilliard School. The schedule is as follows: July 5 and 6 Complete incidental music to Les Fils des Etoiles (1891) and Three Sarabandes (1887) Emily George, piano July 12 and 13 Music by Bach, Mozart, Rameau, Byrd, Couperin, D. Scarlatti, Clementi, and Satie Emily George, piano July 19 and 20 Veritables Preludes flasques (pour un chien) (1912), Descriptions automatiques (1913), Embryons desseches (1913), Croquis et agaceries d'un gros bonhomme en bois (1913), Chapitres tournes en tous sens (1913), Vieux sequins et vielles cuirasses (1913), Enfantines (1913), Heures secuTaires et instantanees (1914), Les Trois Valses distinguees du precieux degoute (1914), and Avant-dernieres pensees (1915) Michael Torre, piano Friday and Saturday evenings in the Sculpture Garden of The Museum of Modern Art are made possible in part by NYNEX West 53 Street, New York, NY. 10019-5498 Tel: 212-708-9850 C :RNART Telex: 62370 Mi 2 July 26 and 27 Les Heures Persanes (1916-19) Charles Koechlin Karen Becker, piano August -

Brian Eno • • • His Music and the Vertical Color of Sound

BRIAN ENO • • • HIS MUSIC AND THE VERTICAL COLOR OF SOUND by Eric Tamm Copyright © 1988 by Eric Tamm DEDICATION This book is dedicated to my parents, Igor Tamm and Olive Pitkin Tamm. In my childhood, my father sang bass and strummed guitar, my mother played piano and violin and sang in choirs. Together they gave me a love and respect for music that will be with me always. i TABLE OF CONTENTS DEDICATION ............................................................................................ i TABLE OF CONTENTS........................................................................... ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ....................................................................... iv CHAPTER ONE: ENO’S WORK IN PERSPECTIVE ............................... 1 CHAPTER TWO: BACKGROUND AND INFLUENCES ........................ 12 CHAPTER THREE: ON OTHER MUSIC: ENO AS CRITIC................... 24 CHAPTER FOUR: THE EAR OF THE NON-MUSICIAN........................ 39 Art School and Experimental Works, Process and Product ................ 39 On Listening........................................................................................ 41 Craft and the Non-Musician ................................................................ 44 CHAPTER FIVE: LISTENERS AND AIMS ............................................ 51 Eno’s Audience................................................................................... 51 Eno’s Artistic Intent ............................................................................. 55 “Generating and Organizing Variety in -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 48,1928-1929, Trip

CARNEGIE HALL .... NEW YORK Thursday Evening, January 31, at 8.30 Saturday Afternoon, February 2, at 2.30 %; BOSTON SYAPHONY 0RO1ESTRS INC. ORTY-EIGHTH SEASON Wfc) J928-J929 Np • ' it PR5GR7W1E 5 P^L. IMS CHOOSE YOUR PIANO AS THE ARTISTS DO PIANO One of the beautiful New Baldwin Models An Announcement of Js[ew Models Distinctive triumphs of piano Baldwin yourself, will you craftsmanship, pianos which fully appreciate what Baldwin attain the perfection sought by craftsmen have accomplished. world famous pianists. ((Spon' C[ Come to our store today and sored by the ideals by which make the acquaintance of this these artists have raised them' new achievement in piano selves to the very pinnacle of making. (( Grands at $1450 recognition. (( Only when and up, in mahogany. you hear and play the new palbtom pano Company 20 EAST 54th STREET NEW YORK CITY CARNEGIE HALL NEW YORK Forty-third Season in New York FORTY-EIGHTH SEASON 1928-1929 INC. SERGE KOUSSEVITZKY, Conductor THURSDAY EVENING, JANUARY 31, at 8.30 AND THE SATURDAY AFTERNOON, FEBRUARY 2, at 2.30 WITH HISTORICAL AND DESCRIPTIVE NOTES BY PHILIP HALE COPYRIGHT, 1929, BY BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA, INC. THE OFFICERS AND TRUSTEES OF THE BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA, Inc. FREDERICK P. CABOT President BENTLEY W. WARREN Vice-President ERNEST B. DANE Treasurer FREDERICK P. CABOT FREDERICK E. LOWELL ERNEST B. DANE ARTHUR LYMAN N. PENROSE HALLOWELL EDWARD M. PICKMAN M. A. DE WOLFE HOWE HENRY B. SAWYER JOHN ELLERTON LODGE BENTLEY W WARREN W. H. BRENNAN, Manager G. E. JUDD, Assistant Manager NT OF THE IMMOR.TALS 'THE MAGIC FIRE SPELL," painted /or the STEINWAY COLLECTION hy "N. -

Give a Dog a Bone Some Investigations Into Erik Satie

Give a dog a bone Some investigations into Erik Satie An article by Ornella Volta. Original title: Le rideau se leve sur un os. From Revue International de la Musique Francaise, Vol. 8, No. 23. English translation by Todd Niquette. © 1987: Reprinted and translated with kind permission. Satie said one day to Cocteau: "I want to write a play for dogs, and I already have my set design: the curtain rises on a bone". It often happens with Satie that, amazed by the arresting image he suggests, we forget to dig for meaning beneath the proposal. Such a magic formula - we're happy just to mull it over, even pass it on, to transmit it intact. Why ask ourselves about the details of such a play? About its plot, its dialogue? Why did he go out of his way to describe the set? Unpublished drawing by Jean Sichler (1987) Simply to raise the question touches on the pedantic or superfluous. In a play "for dogs," the bone is at once the content, the set and the plot. The set is the play. It has often been asked why Satie wrote several of his works "for a dog". Some have seen an allusion to Chopin's Valse op. 64, no. 1 nicknamed "little dog's waltz" - or maybe a sly wink at the "Love Songs To My Dog" (Sins of Old Age) by Rossini. Others have seen, perhaps a bit more to the point, a tribute to Diogenes and other Cynics. For us, as we have written elsewhere, the dedication of the Flabby Preludes sends us back, automatically and inevitably, to the prologue of Gargantua, which begins by quoting the same portion of the "Banquet" which Satie would use in his "Portrait de Socrate". -

Yhtenäistetty Erik Satie

Suomen musiikkikirjastoyhdistyksen julkaisusarja 126 Yhtenäistetty Erik Satie Teosten yhtenäistettyjen nimekkeiden ohjeluettelo Heikki Poroila Suomen musiikkikirjastoyhdistys Helsinki 2012 Julkaisija Suomen musiikkikirjastoyhdistys Ulkoasu Heikki Poroila © Heikki Poroila 2012 Neljäs laitos, verkkoversio 2.0 Kannen kuva: Marcellin Desboutin (1823-1902) 01.4 Poroila, Heikki Yhtenäistetty Erik Satie : Yhtenäistettyjen nimekkeiden ohjeluettelo. – Helsinki : Suomen musiik- kikirjastoyhdistys, 2012. – Neljäs laitos, verkkoversio 2.0 – 28 s. – (Suomen musiikkikirjastoyhdis- tyksen julkaisusarja, ISSN 0784-0322 ; 126). – ISBN 952-5363-25-2 (PDF) ISBN 952-5363-25-2 (PDF) Yhtenäistetty Erik Satie 2 Luettelon käyttäjälle ERIK SATIE (Éric Alfred Leslie Satie, 17.5.1866 Honfleur – 1.7.1925 Pariisi) välttelee säveltäjänä lokerointia, vaikka esiintyykin usein yhdessä Debussyn ja Ravelin kaltaisten aikalaistensa seurassa. Satien musiikkia on toisaalta yritetty määritellä naiivin amatöörimäisyyden, toisaalta aikaansa edel- lä olleen rohkean kokeilun näkökulmasta. Satie itse olisi todennäköisesti hyväksynyt kaikki määri- telmät, häntä itseään kiinnosti enemmän vapaus kokeilla kaikenlaista. 1900-luvun toisella puoliskolla Satie nousi suureen suosioon sekä monien sävellystensä yksinker- taisen viehättävyyden että humorististen nimien ansiosta. Säveltäjän ns. taidemusiikkituotanto on levytetty melko kattavasti, pianomusiikki useampaan kertaankin. Vähemmälle huomiolle on jäänyt Satien rooli kabareelaulujen tekijänä, mikä rooli varsinkin elämän alkupuolella -

A L'occasion Du 150Ème Anniversaire De La Naissance D'erik Satie, Compositeur Et Pianiste Français Né En 1866 Et Mort En

A l’occasion du 150ème anniversaire de la naissance d’Erik Satie, compositeur et pianiste français né en 1866 et mort en 1925, l’Espace musique de la Médiathèque de Vincennes vous propose un focus documentaire sur son œuvre. Erik Satie occupe une place particulière dans la création musicale française. Rattaché à la musique moderne du XXème siècle, cet excentrique et provocateur s’appliqua néanmoins toute sa vie à composer une musique en décalage avec le conformisme artistique du moment, que ce soit le romantisme, l’impressionnisme ou le wagnérisme. Connu pour son style particulier, caustique et personnel, il est qualifié de visionnaire et précurseur, notamment de la musique graphique (avec ses partitions calligraphiées et accompagnées de dessins et de poèmes) et de ce qu’il a appelé la « musique d’ameublement », qui se rapporte à ce qu’on appelle aujourd’hui la « musique d’ambiance ». Ses premières pièces pour son instrument de prédilection : le piano – emblématiques de son style minimaliste, dont ses fameuses Gymnopédies et Gnossiennes, mais surtout Vexations – servent par exemple de référence aux adeptes de la musique répétitive et conceptuelle. Cultivant avec finesse son goût pour l’autodérision, Erik Satie se distingue aussi par ses œuvres humoristiques et fantasques ; d’où sa quantité de pièces brèves aux titres incongrus (Morceaux en forme de poire, Véritables préludes flasques (pour un chien) ou Valses du précieux dégoûté) et parsemées d’annotations cocasses et souvent ironiques ; ce qui parallèlement, ne l’empêche pas de composer quelques chefs-d’œuvre de plus grande ambition comme son drame symphonique Socrate, son ballet « cubiste » Parade (en collaboration avec Cocteau et Picasso pour les Ballets russes) ou encore En habit de cheval, qui contient des fugues et du contrepoint. -

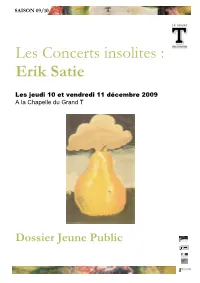

Dossier Erik Satie

SAISON 09/10 Les Concerts insolites : Erik Satie Les jeudi 10 et vendredi 11 décembre 2009 A la Chapelle du Grand T Dossier Jeune Public Sommaire Le s Concerts insolites p.4 Erik Satie, compositeur et pianiste p.5 L’Ensemble Skênê p.9 Catherine Verhelst et Hervé Tougeron, directeurs p.9 artistique de l’Ensemble Skênê Quelques dessins et écrits d’Erik Satie p.11 2 Les Concerts insolites : Erik Satie Par L’Ensemble Skênê Musique, texte et dessins Erik Satie Conception et création vidéo Hervé Tougeron et Catherine Verhelst Avec Akié Kakehi mezzo-soprano Catherine Verhelst piano Hervé Tougeron comédien Production Skênê Productions Coréalisation Le Grand T, Musique et Danse 44 (avec la complicité du C.R.R. de Nantes) Conventions avec La DRAC des Pays de Loire, la Région des Pays de la Loire, la Ville de Nantes, le Département de la Loire-Atlantique et la Sacem. En partenariat avec la Maïf Les jeudi 10 et vendredi 11 décembre 2009 à la Chapelle du Grand T à 20h Durée du spectacle : A préciser ultérieurement Tarif : 6€ par élève ou un pass-culture Attention ! Il n’y a pas de navette vers le centre-ville à l’issue des spectacles programmés à la Chapelle du Grand T 3 Les Concerts insolites et Erik Satie La musique est un moyen de transport rapide « Les Concerts insolites ont été imaginés par Catherine Verhelst et Hervé Tougeron comme une manière musicale, théâtrale et visuelle, propre à l’Ensemble Skênê, de faire découvrir les œuvres fortes et généreuses de compositeurs de notre temps. -

Satie Intégrale De La Musique Pour Piano • 1 Nouvelle Édition Salabert

comprenant DES PREMIERS ENREGISTREMENTS MONDIAUX SATIE INTÉGRALE DE LA MUSIQUE POUR PIANO • 1 NOUVELLE ÉDITION SALABERT NICOLAS HORVATH ERIK SATIE (1866-1925) INTÉGRALE DE LA MUSIQUE POUR PIANO • 1 NOUVELLE ÉDITION SALABERT NICOLAS HORVATH, Piano Numéro de catalogue : GP761 Date d’enregistrement : 9-11 décembre 2014 Lieu d’enregistrement : Villa Bossi, Bodio, Italie Éditeur : Editions Salabert (2016) Piano : Érard de Cosima Wagner, modèle 55613, année 1881 Producteur et Éditeur : Alexis Guerbas (Les Rouages) Ingénieur du son : Ermanno De Stefani Rédaction du livret : Robert Orledge Traduction française : Nicolas Horvath Photographies de l’artiste : Laszlo Horvath Portrait du compositeur : Satie dans une ogive © Archives Erik Satie Coll. Priv. Couverture : Sigrid Osa L’artiste tient à remercier sincèrement Ornella Volta et la Fondation Erik Satie. 2 1 ALLEGRO (1884) ** 00:29 2 VALSE-BALLET (1885) 01:59 3 FANTAISIE-VALSE (?1885-87) 02:17 4 1er QUATUOR (?1886) * 01:04 5 2ème QUATUOR (?1886) * 00:33 OGIVES (?1886) 07:27 6 Ogive I 01:42 7 Ogive II ** 02:22 8 Ogive III 01:39 9 Ogive IV 01:44 TROIS SARABANDES (1887) ** 14:23 0 Sarabande 1 04:35 ! Sarabande 2 04:04 @ Sarabande 3 05:44 TROIS GYMNOPÉDIES (1888) 11:04 # 1er Gymnopédie 04:17 $ 2ème Gymnopédie 03:32 % 3ème Gymnopédie 03:15 ^ GNOSSIENNE [N° 5] (1889) ** 03:28 & CHANSON HONGROISE (1889) ** 00:35 * PREMIER ENREGISTREMENT MONDIAL ** PREMIER ENREGISTREMENT MONDIAL DE LA VERSION RÉVISÉE PAR ROBERT ORLEDGE 3 TROIS GNOSSIENNES (?1890-1893) 10:09 * 1ère Gnossienne 04:55 ( 2ème Gnossienne 02:19 -

The Uses and Aesthetics of Musical Borrowing in Erik Satie's Humoristic

Copyright by Belva Jean Hare 2005 The Dissertation Committee for Belva Jean Hare certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: The Uses and Aesthetics of Musical Borrowing in Erik Satie’s Humoristic Piano Suites, 1913-1917 Committee: ______________________________ Marianne Wheeldon, Supervisor ______________________________ Byron Almén ______________________________ James Buhler ______________________________ Jean-Pierre Cauvin ______________________________ David Neumeyer The Uses and Aesthetics of Musical Borrowing in Erik Satie’s Humoristic Piano Suites, 1913-1917 by Belva Jean Hare, B.M., M.M. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin December 2005 To Chris, for supporting me in every way possible, and for loving me. Acknowledgements First and foremost, I would like to thank Marianne Wheeldon for challenging me, for guiding me, and most of all for sharing with me a love of Satie’s music. I am also deeply indebted to my committee, Byron Almén, Jim Buhler, Jean-Pierre Cauvin, and David Neumeyer, as well as to Stephen Wray, for their helpfulness and patience as I wrote this dissertation from a distance. I thank Jann Pasler for encouraging me to pursue study of Satie’s music and Steven Moore Whiting for providing me with a hard-to-find source. I also owe so much to my family for their encouragement through the years, which helped keep me on track more than they realize. I couldn’t begin to thank you all enough.