Open Boerner Thesis.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Against Expression?: Avant-Garde Aesthetics in Satie's" Parade"

Against Expression?: Avant-garde Aesthetics in Satie’s Parade A thesis submitted to the Division of Graduate Studies and Research of the University of Cincinnati In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC In the division of Composition, Musicology, and Theory of the College-Conservatory of Music 2020 By Carissa Pitkin Cox 1705 Manchester Street Richland, WA 99352 [email protected] B.A. Whitman College, 2005 M.M. The Boston Conservatory, 2007 Committee Chair: Dr. Jonathan Kregor, Ph.D. Abstract The 1918 ballet, Parade, and its music by Erik Satie is a fascinating, and historically significant example of the avant-garde, yet it has not received full attention in the field of musicology. This thesis will provide a study of Parade and the avant-garde, and specifically discuss the ways in which the avant-garde creates a dialectic between the expressiveness of the artwork and the listener’s emotional response. Because it explores the traditional boundaries of art, the avant-garde often resides outside the normal vein of aesthetic theoretical inquiry. However, expression theories can be effectively used to elucidate the aesthetics at play in Parade as well as the implications for expressability present in this avant-garde work. The expression theory of Jenefer Robinson allows for the distinction between expression and evocation (emotions evoked in the listener), and between the composer’s aesthetical goal and the listener’s reaction to an artwork. This has an ideal application in avant-garde works, because it is here that these two categories manifest themselves as so grossly disparate. -

Borderline Research

Borderline Research Histories of Art between Canada and the United States, c. 1965–1975 Adam Douglas Swinton Welch A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Art University of Toronto © Copyright by Adam Douglas Swinton Welch 2019 Borderline Research Histories of Art between Canada and the United States, c. 1965–1975 Adam Douglas Swinton Welch Doctor of Philosophy Department of Art University of Toronto 2019 Abstract Taking General Idea’s “Borderline Research” request, which appeared in the first issue of FILE Megazine (1972), as a model, this dissertation presents a composite set of histories. Through a comparative case approach, I present eight scenes which register and enact larger political, social, and aesthetic tendencies in art between Canada and the United States from 1965 to 1975. These cases include Jack Bush’s relationship with the critic Clement Greenberg; Brydon Smith’s first decade as curator at the National Gallery of Canada (1967–1975); the exhibition New York 13 (1969) at the Vancouver Art Gallery; Greg Curnoe’s debt to New York Neo-dada; Joyce Wieland living in New York and making work for exhibition in Toronto (1962–1972); Barry Lord and Gail Dexter’s involvement with the Canadian Liberation Movement (1970–1975); the use of surrogates and copies at the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design (1967–1972); and the Eternal Network performance event, Decca Dance, in Los Angeles (1974). Relying heavily on my work in institutional archives, artists’ fonds, and research interviews, I establish chronologies and describe events. By the close of my study, in the mid-1970s, the movement of art and ideas was eased between Canada and the United States, anticipating the advent of a globalized art world. -

Nicolas Horvath Erik Satie (1866-1925) Intégrale De La Musique Pour Piano • 2 Nouvelle Édition Salabert

SATIE INTÉGRALE DE LA MUSIQUE POUR PIANO • 2 NOUVELLE ÉDITION SALABERT LE FILS DES ÉTOILES NICOLAS HORVATH ERIK SATIE (1866-1925) INTÉGRALE DE LA MUSIQUE POUR PIANO • 2 NOUVELLE ÉDITION SALABERT LE FILS DES ÉTOILES NICOLAS HORVATH, Piano Numéro de catalogue : GP762 Date d’enregistrement : 10 décembre 2014 Lieu d’enregistrement : Villa Bossi, Bodio, Italie Publishers: Durand/Salabert/Eschig 2016 Edition Piano : Érard de Cosima Wagner, modèle 55613, année 1881 Producteur et Éditeur : Alexis Guerbas (Les Rouages) Ingénieur du son : Ermanno De Stefani Rédaction du livret : Robert Orledge Traduction française : Nicolas Horvath Photographies de l’artiste : Laszlo Horvath Portrait du compositeur : Paul Signac, (c. 1890, Crayon Conté on paper) © Musée d’Orsay, Paris Cover Art: Sigrid Osa L’artiste tient à remercier sincèrement Ornella Volta et la Fondation Erik Satie. 2 LE FILS DES ÉTOILES (?1891) * 73:56 1 Prélude de l’Acte 1 – La Vocation 03:53 2 Autre musique pour le Premier Acte 21:28 3 Prélude de l’Acte 2 – L’Initiation 03:25 4 Autre musique pour le Deuxième Acte 20:59 5 Prélude de l’Acte 3 – L’Incantation 05:10 6 Autre musique pour le Troisième Acte 18:38 7 FÊTE DONNÉE PAR DES CHEVALIERS NORMANDS EN L’HONNEUR D’UNE JEUNE DEMOISELLE (XIe SIÈCLE) (1892) 03:08 * PREMIER ENREGISTREMENT MONDIAL DURÉE TOTALE: 77:10 DE LA VERSION RÉVISÉE PAR ROBERT ORLEDGE 3 ERIK SATIE (1866-1925) INTÉGRALE DE LA MUSIQUE POUR PIANO • NOUVELLE ÉDITION SALABERT À PROPOS DE NICOLAS HORVATH ET DE LA NOUVELLE ÉDITION SALABERT DES « ŒUVRES POUR PIANO » DE SATIE. En 2014, j’ai été contacté (en tant que professeur de musicologie spécialiste de Satie) par Nicolas Horvath, un jeune pianiste français de renommée internationale, à propos d’un projet d’enregistrement des œuvres complètes pour piano. -

Llyn Foulkes Between a Rock and a Hard Place

LLYN FOULKES BETWEEN A ROCK AND A HARD PLACE LLYN FQULKES BETWEEN A ROCK AND A HARD PLACE Initiated and Sponsored by Fellows ol Contemporary Art Los Angeles California Organized by Laguna Art Museum Laguna Beach California Guest Curator Marilu Knode LLYN FOULKES: BETWEEN A ROCK AND A HARD PLACE This book has been published in conjunction with the exhibition Llyn Foulkes: Between a Rock and a Hard Place, curated by Marilu Knode, organized by Laguna Art Museum, Laguna Beach, California, and sponsored by Fellows of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, California. The exhibition and book also were supported by a grant from the National Endowment for the Arts, Washington, D.C., a federal agency. TRAVEL SCHEDULE Laguna Art Museum, Laguna Beach, California 28 October 1995 - 21 January 1996 The Contemporary Art Center, Cincinnati, Ohio 3 February - 31 March 1996 The Oakland Museum, Oakland, California 19 November 1996 - 29 January 1997 Neuberger Museum, State University of New York, Purchase, New York 23 February - 20 April 1997 Palm Springs Desert Museum, Palm Springs, California 16 December 1997 - 1 March 1998 Copyright©1995, Fellows of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles All rights reserved. No part of the contents of this book may be reproduced, in whole or in part, without permission from the publisher, the Fellows of Contemporary Art. Editor: Sue Henger, Laguna Beach, California Designers: David Rose Design, Huntington Beach, California Printer: Typecraft, Inc., Pasadena, California COVER: That Old Black Magic, 1985 oil on wood 67 x 57 inches Private Collection Photo Credits (by page number): Casey Brown 55, 59; Tony Cunha 87; Sandy Darnley 17; Susan Einstein 63; William Erickson 18; M. -

Nationalism, Primitivism, & Neoclassicism

Nationalism, Primitivism, & Neoclassicism" Igor Stravinsky (1882-1971)! Biographical sketch:! §" Born in St. Petersburg, Russia.! §" Studied composition with “Mighty Russian Five” composer Nicolai Rimsky-Korsakov.! §" Emigrated to Switzerland (1910) and France (1920) before settling in the United States during WW II (1939). ! §" Along with Arnold Schönberg, generally considered the most important composer of the first half or the 20th century.! §" Works generally divided into three style periods:! •" “Russian” Period (c.1907-1918), including “primitivist” works! •" Neoclassical Period (c.1922-1952)! •" Serialist Period (c.1952-1971)! §" Died in New York City in 1971.! Pablo Picasso: Portrait of Igor Stravinsky (1920)! Ballets Russes" History:! §" Founded in 1909 by impresario Serge Diaghilev.! §" The original company was active until Diaghilev’s death in 1929.! §" In addition to choreographing works by established composers (Tschaikowsky, Rimsky- Korsakov, Borodin, Schumann), commissioned important new works by Debussy, Satie, Ravel, Prokofiev, Poulenc, and Stravinsky.! §" Stravinsky composed three of his most famous and important works for the Ballets Russes: L’Oiseau de Feu (Firebird, 1910), Petrouchka (1911), and Le Sacre du Printemps (The Rite of Spring, 1913).! §" Flamboyant dancer/choreographer Vaclav Nijinsky was an important collaborator during the early years of the troupe.! ! Serge Diaghilev (1872-1929) ! Ballets Russes" Serge Diaghilev and Igor Stravinsky.! Stravinsky with Vaclav Nijinsky as Petrouchka (Paris, 1911).! Ballets -

The Cult of Socrates: the Philosopher and His Companions in Satie's Socrate

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU Undergraduate Honors Capstone Projects Honors Program Spring 2013 The Cult of Socrates: The Philosopher and His Companions in Satie's Socrate Andrea Decker Moreno Utah State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/honors Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Moreno, Andrea Decker, "The Cult of Socrates: The Philosopher and His Companions in Satie's Socrate" (2013). Undergraduate Honors Capstone Projects. 145. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/honors/145 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors Program at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Capstone Projects by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE CULT OF SOCRATES: THE PHILOSOPHER AND HIS COMPANIONS IN SATIE’S SOCRATE by Andrea Decker Moreno Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of HONORS IN UNIVERSITY STUDIES WITH DEPARTMENTAL HONORS in Music – Vocal Performance in the Department of Music Approved: Thesis/Project Advisor Departmental Honors Advisor Dr. Cindy Dewey Dr. Nicholas Morrison Director of Honors Program Dr. Nicholas Morrison UTAH STATE UNIVERSITY Logan, UT Spring 2013 The Cult of Socrates: The philosopher and his companions in Satie's Socrate Satie's Socrate is an enigma in the musical world, a piece that defies traditional forms and styles. Satie chose for his subject one of the most revered characters of history, the philosopher Socrates. Instead of evaluating his philosophy and ideas, Satie created a portrait of Socrates from the most intimate moments Socrates spent with his followers in Plato's dialogues. -

Surrealism and Music in France, 1924-1952: Interdisciplinary and International Contexts Friday 8 June 2018: Senate House, University of London

Surrealism and music in France, 1924-1952: interdisciplinary and international contexts Friday 8 June 2018: Senate House, University of London 9.30 Registration 9.45-10.00 Welcome and introductions 10.00-11.00 Session 1: Olivier Messiaen and surrealism (chair: Caroline Potter) Elizabeth Benjamin (Coventry University): ‘The Sound(s) of Surrealism: on the Musicality of Painting’ Robert Sholl (Royal Academy of Music/University of West London): ‘Messiaen and Surrealism: ethnography and the poetics of excess’ 11.00-11.30 Coffee break 11.30-13.00 Session 2: Surrealism, ethnomusicology and music (chair: Edward Campbell) Renée Altergott (Princeton University): ‘Towards Automatism: Ethnomusicology, Surrealism, and the Question of Technology’ Caroline Potter (IMLR, School of Advanced Study, University of London): ‘L’Art magique: the surreal incantations of Boulez, Jolivet and Messiaen’ Edmund Mendelssohn (University of California Berkeley): ‘Sonic Purity Between Breton and Varèse’ 13.00 Lunch (provided) 13.45 Keynote (chair: Caroline Potter) Sébastien Arfouilloux (Université Grenoble-Alpes) : ‘Présences du surréalisme dans la création musicale’ 14.45-15.45 Session 3: Surrealism and music analysis (chair: Caroline Rae) Henri Gonnard (Université de Tours): ‘L’Enfant et les sortilèges (1925) de Maurice Ravel et le surréalisme : l’exemple du préambule féerique de la 2e partie’ James Donaldson (McGill University): ‘Poulenc, Fifth Relations, and a Semiotic Approach to the Musical Surreal’ 15.45-16.15 Coffee break 16.15-17.15 Session 4: Surrealism and musical innovation (chair: Paul Archbold) Caroline Rae (Cardiff University): ‘André Jolivet, Antonin Artaud and Alejo Carpentier: Redefining the Surreal’ Edward Campbell (Aberdeen University): ‘Boulez’s Le Marteau as Assemblage of the Surreal’ 17.15 Concluding remarks 17.45-18.45 Concert: Alexander Soares, Chancellor’s Hall Programme André Jolivet: Piano Sonata no. -

Florida State University Libraries

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2009 Gustav Mahler, Alfred Roller, and the Wagnerian Gesamtkunstwerk: Tristan and Affinities Between the Arts at the Vienna Court Opera Stephen Carlton Thursby Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC GUSTAV MAHLER, ALFRED ROLLER, AND THE WAGNERIAN GESAMTKUNSTWERK: TRISTAN AND AFFINITIES BETWEEN THE ARTS AT THE VIENNA COURT OPERA By STEPHEN CARLTON THURSBY A Dissertation submitted to the College of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2009 The members of the Committee approve the Dissertation of Stephen Carlton Thursby defended on April 3, 2009. _______________________________ Denise Von Glahn Professor Directing Dissertation _______________________________ Lauren Weingarden Outside Committee Member _______________________________ Douglass Seaton Committee Member Approved: ___________________________________ Douglass Seaton, Chair, Musicology ___________________________________ Don Gibson, Dean, College of Music The Graduate School has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii To my wonderful wife Joanna, for whose patience and love I am eternally grateful. In memory of my grandfather, James C. Thursby (1926-2008). iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The completion of this dissertation would not have been possible without the generous assistance and support of numerous people. My thanks go to the staff of the Austrian Theater Museum and Austrian National Library-Music Division, especially to Dr. Vana Greisenegger, curator of the visual materials in the Alfred Roller Archive of the Austrian Theater Museum. I would also like to thank the musicology faculty of the Florida State University College of Music for awarding me the Curtis Mayes Scholar Award, which funded my dissertation research in Vienna over two consecutive summers (2007- 2008). -

Erik Satie's Vexations—An Exercise in Immobility Christopher Dawson

Document généré le 23 sept. 2021 22:49 Canadian University Music Review Revue de musique des universités canadiennes Erik Satie's Vexations—An Exercise in Immobility Christopher Dawson Volume 21, numéro 2, 2001 Résumé de l'article La pièce pour piano Vexations d’Erik Satie comporte une « Note de l’auteur » URI : https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1014483ar où le compositeur demande apparemment aux interprètes de répéter le DOI : https://doi.org/10.7202/1014483ar morceau 840 fois. Les opinions des biographes de Satie divergent quant à savoir si Satie voulait ou non une exécution « complète » de la pièce. Dans cet Aller au sommaire du numéro article, l’auteur évalue comment une interprétation littéraire de la Note peut jeter un éclairage sur les intentions de Satie. Il conclut que Vexations n’est pas tant un morceau de bravoure qu’un exercice : un moment musical conçu pour Éditeur(s) dégager les interprètes des notions occidentales conventionnelles de développement linéaire et de réception cumulative, en faveur d’un style Canadian University Music Society / Société de musique des universités musical personnel d’où est absent le développement, et pour les préparer à canadiennes jouer d’autres pièces, telles une Gymnopédie ou une Gnossienne. ISSN 0710-0353 (imprimé) 2291-2436 (numérique) Découvrir la revue Citer cet article Dawson, C. (2001). Erik Satie's Vexations—An Exercise in Immobility. Canadian University Music Review / Revue de musique des universités canadiennes, 21(2), 29–40. https://doi.org/10.7202/1014483ar All Rights Reserved © Canadian University Music Society / Société de musique Ce document est protégé par la loi sur le droit d’auteur. -

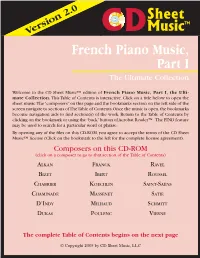

Table of Contents Is Interactive

Sheet TM Version 2.0 CDMusic 1 French Piano Music, Part I The Ultimate Collection Welcome to the CD Sheet Music™ edition of French Piano Music, Part I, the Ulti- mate Collection. This Table of Contents is interactive. Click on a title below to open the sheet music. The “composers” on this page and the bookmarks section on the left side of the screen navigate to sections of The Table of Contents.Once the music is open, the bookmarks become navigation aids to find section(s) of the work. Return to the Table of Contents by clicking on the bookmark or using the “back” button of Acrobat Reader™. The FIND feature may be used to search for a particular word or phrase. By opening any of the files on this CD-ROM, you agree to accept the terms of the CD Sheet Music™ license (Click on the bookmark to the left for the complete license agreement). Composers on this CD-ROM (click on a composer to go to that section of the Table of Contents) ALKAN FRANCK RAVEL BIZET IBERT ROUSSEL CHABRIER KOECHLIN SAINT-SAËNS CHAMINADE MASSENET SATIE D’INDY MILHAUD SCHMITT DUKAS POULENC VIERNE The complete Table of Contents begins on the next page © Copyright 2005 by CD Sheet Music, LLC Sheet TM Version 2.0 CDMusic 2 VALENTIN ALKAN IV. La Bohémienne Saltarelle, Op. 23 V. Les Confidences Prélude in B Major, from 25 Préludes, VI. Le Retour Op. 31, No. 3 Variations Chromatiques de concert Symphony, from 12 Études Nocturne in D Major I. Allegro, Op. 39, No. -

Nicolas Horvath Erik Satie (1866-1925) Intégrale De La Musique Pour Piano • 3 Nouvelle Édition Salabert

comprenant DES PREMIERS ENREGISTREMENTS MONDIAUX SATIE INTÉGRALE DE LA MUSIQUE POUR PIANO • 3 NOUVELLE ÉDITION SALABERT NICOLAS HORVATH ERIK SATIE (1866-1925) INTÉGRALE DE LA MUSIQUE POUR PIANO • 3 NOUVELLE ÉDITION SALABERT NICOLAS HORVATH, Piano Numéro de catalogue : GP763 Date d’enregistrement : 11 décembre 2014 Lieu d’enregistrement : Villa Bossi, Bodio, Italie Publishers: Durand/Salabert/Eschig 2016 Edition Piano : Érard de Cosima Wagner, modèle 55613, année 1881 Producteur et Éditeur : Alexis Guerbas (Les Rouages) Ingénieur du son : Ermanno De Stefani Rédaction du livret : Robert Orledge Traduction française : Nicolas Horvath Photographies de l’artiste : Laszlo Horvath Portrait du compositeur : Santiago Rusiñol Una romanza ©MNAC Couverture : Sigrid Osa L’artiste tient à remercier sincèrement Ornella Volta et la Fondation Erik Satie. 2 1 PRÉLUDE DU NAZARÉEN [EN DEUX PARTIES] ** 10:23 uspud – ballet chrétien en trois actes ** 23:53 2 Acte 1 09:33 3 Acte 2 06:20 4 Acte 3 07:53 5 EGINHARD. PRÉLUDE 02:04 6 DANSES GOTHIQUES ** 10:34 7 VEXATIONS 07:01 8 SANS TITRE, PEUT-ÊTRE POUR LA MESSE DES PAUVRES, [MODÉRÉ] 01:04 9 PRÉLUDE DE « LA PORTE HÉROÏQUE DU CIEL » ** 04:50 0 GNOSSIENNE [N° 6] 02:17 ! SANS TITRE, ?GNOSSIENNE [PETITE OUVERTURE À DANSER] ** 02:09 PIÈCES FROIDES : AIRS À FAIRE FUIR 10:00 @ D’une manière très particulière 04:30 # Modestement 01:09 $ S’inviter ** 04:19 % AIRS À FAIRE FUIR N° 2 (version plus chromatique) * 00:26 PIÈCES FROIDES : DANSES DE TRAVERS ** 06:25 ^ En y regardant à deux fois 02:02 & Passer 01:44 * Encore 02:37 ( DANSE DE TRAVERS II ** 03:12 * PREMIER ENREGISTREMENT MONDIAL DURÉE TOTALE: 85:03 ** PREMIER ENREGISTREMENT MONDIAL DE LA VERSION RÉVISÉE PAR ROBERT ORLEDGE 3 ERIK SATIE (1866-1925) INTÉGRALE DE LA MUSIQUE POUR PIANO • 3 NOUVELLE ÉDITION SALABERT À PROPOS DE NICOLAS HORVATH ET DE LA NOUVELLE ÉDITION SALABERT DES « ŒUVRES POUR PIANO » DE SATIE. -

Erik Satie's Letters Nigel Wilkins

Document généré le 1 oct. 2021 02:34 Canadian University Music Review Revue de musique des universités canadiennes Erik Satie's Letters Nigel Wilkins Numéro 2, 1981 URI : https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1013751ar DOI : https://doi.org/10.7202/1013751ar Aller au sommaire du numéro Éditeur(s) Canadian University Music Society / Société de musique des universités canadiennes ISSN 0710-0353 (imprimé) 2291-2436 (numérique) Découvrir la revue Citer cet article Wilkins, N. (1981). Erik Satie's Letters. Canadian University Music Review / Revue de musique des universités canadiennes, (2), 207–227. https://doi.org/10.7202/1013751ar All Rights Reserved © Canadian University Music Society / Société de musique Ce document est protégé par la loi sur le droit d’auteur. L’utilisation des des universités canadiennes, 1981 services d’Érudit (y compris la reproduction) est assujettie à sa politique d’utilisation que vous pouvez consulter en ligne. https://apropos.erudit.org/fr/usagers/politique-dutilisation/ Cet article est diffusé et préservé par Érudit. Érudit est un consortium interuniversitaire sans but lucratif composé de l’Université de Montréal, l’Université Laval et l’Université du Québec à Montréal. Il a pour mission la promotion et la valorisation de la recherche. https://www.erudit.org/fr/ ERIK SATIE'S LETTERS Nigel Wilkins Although a substantial collection of letters written by Erik Satie was gathered together several years ago, little of this has appeared in print, either in the original French or in transla• tion, for reasons which I indicated in a previous article dealing with letters concerning Satie's stage works, and those to Darius Milhaud (see Wilkins 1980a).