Polaroid, Ansel Adams and Aperture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

February/March 2014

The PHOTO REVIEW NEWSLETTER February / March 2014 Robert Heinecken Cybill Shepherd/Phone Sex. 1992, dye bleach print on foamcore, 63"×17”. (The Robert Heinecken Trust, Chicago; courtesy Petzel Gallery, New York. © 2013 The Robert Heinecken Trust) At the Museum of Modern Art, New York Exhibitions PHILADELPHIA AREA Germán Gomez “Deconstructing Cities and Duos,” Bridgette Mayer Gallery, 709 Walnut St., Philadelphia, PA 19106, 215/413– Alien She Vox Populi, 319 N. 11th St., 3rd fl., Philadelphia, PA 8893, www.bridgettemayergallery.com, T–Sat 11–5:30 and by 19107, 215/23 8-1236, www.voxpopuligallery.org, T–Sun 12–6, appt., through February 22. March 7 – April 27. Includes photography. Graffiti, Murals, and Tattoos “Paired,” Bucks County Project Artists of a Certain Age Philadelphia Episcopal Cathedral, Gallery, 252 W. Ashland St., Doylestown, PA 18901, 267/247- 3723 Chestnut St., Philadelphia, PA 19104, 267/386-0234 x104, 6634, www.buckscountyprojectgallery.com, Th–F 12–4, F–Sat daily 10–4 and by appt., through February 28. Includes photogra- 1–5, March 8 – April 6. phy by William Brown and Arlene Love. David Graham “Thirty-Five Years / 35 Pictures,” Gallery 339, Donald E. Camp/Lydia Panas/Lori Waselchuk “Humankind,” 339 S. 21st St., Philadelphia, PA 19103, 215/731-1530, www.gal- Main Line Art Center, 746 Panmure Rd., Haverford, PA 19041, lery339.com, T–Sat 10–6, through March 15. 610/525-0272, www.mainlineart.org, M–Th 10–8, F–Sun 10–4, through March 20. Reception, Friday, February 21, 6–8 PM. Panel Jefferson Hayman Wexler Gallery, 201 N. 3rd St., Philadelphia, Discussion and Book Signing, Wednesday, March 19, 6–8 PM. -

P H O T O N E W S L E T T

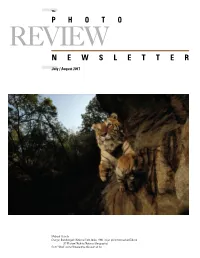

The PHOTO REVIEW NEWSLETTER July / August 2017 Michael Nichols Charger, Bandhavgarh National Park, India, 1996, inkjet print mounted on Dibond (© Michael Nichols/National Geographic) From “Wild” at the Philadelphia Museum of Art Exhibitions PHILADELPHIA AREA T. R. Ericsson The Print Center, 1614 Latimer St., Philadel- phia, PA 19103, 215/735-6090, www.printcenter.org, T–Sat 11–6, Annual Alumni Exhibition The Galleries at Moore, Moore through August 6. College of Art and Design, 20th St. & the Parkway, Philadelphia, PA 19103, 215/965-4027, www.moore.edu, M–Sat 11–5, through Judy Gelles “Fourth Grade Project in Yakima, Washington,” August 19. The Center for Emerging Visual Artists, Bebe Benoliel Gallery at the Barclay, 237 S. 18th St., Suite 3A, Philadelphia, PA 19103, Another Way of Telling: Women Photographers from the Col- 215/546-7775, www.cfeva.org, M–F 11–4, through July 28. lection The Philadelphia Museum of Art, Perelman Building, Julien Levy Gallery, 2525 Pennsylvania Ave., Philadelphia, PA Christopher Kennedy “Re-Imagined,” The Studio Gallery, 19130, 215/684-7695, www.philamuseum.org, T–Sun 10–5, W & 19 W. Mechanic St., New Hope, PA 18930, 215/738-1005, thestu- F 10–8:45, through July 16. dionewhope.com, W–Sun 11–6, through July 30. A Romantic Youth: Advanced Teen Photo Philadelphia Photo Arts Center, 1400 N. American St., Ste. 103, Philadelphia, PA 19122, 215/232-5678, www.philaphotoarts.org, T–Sat 10–6, through July 8. Christopher Kennedy: A Vision of Cubicity, from Impalpable Light at the Bazemore Gallery, Manayunk, PA Christopher Kennedy “Impalpable Light,” The Bazmore Gal- lery, 4339 Main St., Manayunk, PA 19127, 215/482-1119, www. -

The History of Photography: the Research Library of the Mack Lee

THE HISTORY OF PHOTOGRAPHY The Research Library of the Mack Lee Gallery 2,633 titles in circa 3,140 volumes Lee Gallery Photography Research Library Comprising over 3,100 volumes of monographs, exhibition catalogues and periodicals, the Lee Gallery Photography Research Library provides an overview of the history of photography, with a focus on the nineteenth century, in particular on the first three decades after the invention photography. Strengths of the Lee Library include American, British, and French photography and photographers. The publications on French 19th- century material (numbering well over 100), include many uncommon specialized catalogues from French regional museums and galleries, on the major photographers of the time, such as Eugène Atget, Daguerre, Gustave Le Gray, Charles Marville, Félix Nadar, Charles Nègre, and others. In addition, it is noteworthy that the library includes many small exhibition catalogues, which are often the only publication on specific photographers’ work, providing invaluable research material. The major developments and evolutions in the history of photography are covered, including numerous titles on the pioneers of photography and photographic processes such as daguerreotypes, calotypes, and the invention of negative-positive photography. The Lee Gallery Library has great depth in the Pictorialist Photography aesthetic movement, the Photo- Secession and the circle of Alfred Stieglitz, as evidenced by the numerous titles on American photography of the early 20th-century. This is supplemented by concentrations of books on the photography of the American Civil War and the exploration of the American West. Photojournalism is also well represented, from war documentary to Farm Security Administration and LIFE photography. -

For Immediate Release Arrangements by Marie Cosindas January 16Th

For Immediate Release Arrangements by Marie Cosindas January 16th – March 8, 2014 Almost fifty years after her first museum exhibition, Bruce Silverstein Gallery is honored to present Arrangements by Marie Cosindas, featuring thirty-five of the artist’s photographs from the 1960s-80s. In addition to images that have never been exhibited, this show includes works from the historic Museum of Modern Art exhibition of her color photographs in 1966. Arrangements is Cosindas' term for her richly layered assemblages created primarily in her Boston studio, and in later years, around the world, from found or borrowed objects—fabrics, flowers, figurines, jewelry, perfume bottles, tarot cards and other such treasures which came to define her signature style. Often pyramidal in structure, the artist's baroque compositions are filled with an old world style of excess delightfully bordering on kitsch. Cosindas prefers the term Arrangement to “still life” for this body of work, as she wishes to highlight the very active role she played in the construction of these images as well as the intense engagement required from the viewer in order to absorb their varied textures, patterns, colors and minute details. For Cosindas, the resulting image and viewing experience is anything but still. Now reemerging as a cult figure in this medium, Cosindas was one of America’s best-known photographers in the 1960s-80s following her exhibitions at MoMA (her first solo show, and a pioneering feat for a woman artist in this period), the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, 1966; the Chicago Art Institute, 1967; the International Center of Photography, 1978; and John Szarkowski’s landmark exhibition, Mirrors and Windows, 1978. -

Facts About the Polaroid Collections

Contact: Barbara Hitchcock Tel: (617) 429-8600 [email protected] [email protected] FACTS ABOUT THE POLAROID COLLECTIONS What are the Polaroid Collections? The Polaroid Collections consist of more than 16,000 fine art photographs accrued over the lifetime of the Polaroid Corporation, which was founded in 1947. The late Edwin H. Land, inventor, scientist, educator and founder of Polaroid, said when his revolutionary instant sepia film was announced to the world, “The purpose of inventing instant photography was essentially aesthetic – to make available a new medium of expression to numerous individuals who have an artistic interest in the world around them.” This private and priceless corporate treasury of photographs is protected in environmentally controlled archives at a Polaroid facility located near the company’s headquarters in Massachusetts. The Polaroid Collections serve to chronicle the heritage and scientific innovations of Polaroid photography and allow the general public to view world-class art, while providing technical awareness and inspiration for artists and photographers. The Polaroid Collections are a corporate legacy of culture. Exhibits curated from the constantly expanding Polaroid Collections traveled the globe as well as circulate within the United States. In museums, Polaroid fine art photography is included in the permanent collections of London’s Victoria and Albert Museum, the Centre Georges Pompidou in Paris, Amsterdam’s Stedelijk Museum, and the Museum of Modern Art in New York. Why did Polaroid start collecting? Dr. Land’s recognition that artistic vision might test the true limits of Polaroid film led him to integrate the aesthetic dimension of photography into his company’s scientific research. -

Finding Aid for The

1 FINDING AID FOR THE ANSEL ADAMS ARCHIVE AG31 Center for Creative Photography The University of Arizona Tucson, AZ 85721-0103 For further information about the archives at the Center for Creative Photography, please contact the Archivist: phone 520-621-6273; fax 520-621-9444 TABLE OF CONTENTS page number Description, Provenance, Restrictions 2 Scope and Content 2-3 Organization of the Collection 3-4 Correspondence 5-25 Correspondence Index 25-30 Biographical materials 30-33 Music related materials 34-36 Activity Files 36-97 Clippings 97 Publications 97-101 Audio-visual Materials 101-106 Memorabilia 106-107 Photographic Materials 107-118 Photographic Equipment 118-122 Appendix A: Periodicals and miscellaneous, by and about Adams Appendix B: Monographs by and about Adams Appendix C: Personal library: monographs by others Appendix D: Index to photographs in the Ansel Adams Archive Ansel Adams Archive, Center for Creative Photography, The University of Arizona 1 2 DESCRIPTION Papers, photographic materials, and memorabilia, 1920s -1984, of Ansel Adams (1902 - 1984), photographer, author, teacher and conservationist. Includes correspondence (1906 - 1984) between Adams and his family, friends, business associates, and other artists; activity files documenting his commercial projects (1930s - 1977); exhibitions (1936 - 1983); his associations with the Sierra Club (1937 - 1984), Friends of Photography (1967 - 1984), and Images and Words Workshop (1967 - 1972); writings, lectures, and interviews (1931 - 1982); publications with Morgan and Morgan (1950 - 1975), 5 Associates (1952 - 1979), and New York Graphic Society (1973 - 1983); photographic materials including work, reproduction, and exhibition prints; printed materials including reproductions of his work in periodicals and a portion of his personal library; audio and visual materials relating to interviews with him; and memorabilia including awards, certificates, equipment, and clothing. -

Tina Fey Hosts the Golden Globes Down to The

S o C V ΓΡΑΦΕΙ ΤΗΝ ΙΣΤΟΡΙΑ Bringing the news W ΤΟΥ ΕΛΛΗΝΙΣΜΟΥ to generations of E ΑΠΟ ΤΟ 1915 The National Herald Greek- Americans N c v A weekly Greek-AMericAn PublicAtion www.thenationalherald.com VOL. 18, ISSUE 901 January 17-23, 2015 $1.50 Tina Fey Down to the Wire: New Democracy Cuts into SYRIZA’s Lead Hosts the Samaras Hopeful that Momentum Will Be Golden Enough for Reelection on January 25th ATHENS – With polls showing while elevating the anti-austerity the gap between the front-run - SYRIZA. Globes ning major opposition Coalition The latest opinion showed of the Radical Left (SYRIZA) and that New Democracy had closed his ruling New Democracy Con - the gap, that had been as high With Comic Pal servatives closing ahead of the as 3.2 percent, to 1.9 percent as Jan. 25 critical elections, Prime Samaras pounded home warn - Amy Poehler, Minister Antonis Samaras is still ings that a SYRIZA administra - hoping he can overtake his ri - tion –which has promised to Steals the Show vals. redo the Troika terms or walk At stake, he said, is the future away from the debt – could un - By Constantinos E. Scaros of the country. Samaras said the ravel the recovery, push Greece austerity measures he imposed out of the Eurozone and bring Elizabeth Stamatina Fey, bet - on orders of international financial catastrophe. ter known as Tina, whose Greek lenders – which he initially op - According to a nationwide ancestors include a survivor of posed – have worked and opinion poll conducted by Inter - the Chios Massacre of 1822, brought the country to the edge view on behalf of northern stood alongside her lifelong of a recovery from a crushing Greece's Vergina TV on a sample friend and fellow Saturday economic crisis even while cre - of 1,000 people, SYRIZA led with Night Live alumna Amy Poehler ating record unemployment and 28.3 percent but with New as the two comediennes hosted deep poverty while letting tax Democracy right behind at 26.4 the 2015 Golden Globe Awards cheats, politicians, and the rich percent. -

Alew1l'<Eleaje from the ART INSTITUTE of CHICAGO

Alew1l'<eleaJe FROM THE ART INSTITUTE OF CHICAGO ' MICHIGAN ,!\VENUE AT ADAMS STREET, CHICAGO, ILLINOIS, 60603, ..U. S. A. FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE An exhibition of eighty-five Polaroid color. photographs by Marie Cosindas, Boston artist-turned-photographer, opens in the Art Institute of Chicago on January 21 and continues through March 15. The photographs, made by the Polaroid-Land process, are unlike any color photographs made before, says Hugh Edwards, the museum's Curator of Photography. "Marie Cosindas has brought the Polacolor miracle to reflect a world of vision which ranges from poetic fantasies of small objects, flowers and por traits to large spaces of landscape." "Her photographs are as real and as unlikely as butterflies," says John Szarkowski, Museum of Modern Art, New York. "The deeply personal touch, the intimacy which frames her every statement is this poet's birth- right 11 says Perry T. Rathbone, Director, Museumoof Fine Arts, Boston - 'But the rigorous discipline of the trained painter underlies her remarkable articulation of subtle color and design. 11 Marie Cosindas was born in Boston in 1925 and lives there today. She studied design at the Modern School of Design and p�inting and graphics at the Boston Museum School. Her early career was devoted to the teaching of design and to commercial work as a designer and illustrator. On a tour of Greece in 1959 she photographed many subJects as studies for future paintings; however, on returning home, she felt the photographs could stand on their own. This led to her study the following year with the Boston photographer Paul Caponigro, and later with Ansel Adams. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE Eggleston

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE Eggleston, Christenberry, Divola: Color Photography Beyond the New York Reception A Thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Art History by Reva Leigh Main June 2016 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Susan Laxton, Chairperson Dr. Jason Weems Dr. Liz Kotz Copyright by Reva Leigh Main 2016 The Dissertation of Reva Main is approved: Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside Acknowledgments My deepest gratitude to all the U.C. Riverside Art History Department staff and faculty. Sincere thanks to Dr. Susan Laxton for advising and encouraging me throughout the many phases of this project. Your patience and support allowed me to complete this thesis while living 3,000 miles away and working full time—a true challenge. I would also like to thank Dr. Jason Weems and Dr. Liz Kotz for serving as members of my committee, pausing their own sabbaticals to provide me with incredibly helpful feedback; Leigh Gleason, Curator of Collections at the California Museum of Photography, for guiding me in my search to find balance between work and school; and Graduate Coordinator, Alesha Jaennette, for solving my many paperwork crises. I am forever grateful to all of you for your flexibility and understanding. Finally, thank you to my family, friends, and Princeton University Art Museum coworkers for sticking with me through the highs and many lows of this process. Your love and support helped me push through and see this project to completion. iv ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS Eggleston, Christenberry, Divola: Color Photography Beyond the New York Reception by Reva Leigh Main Master of Arts, Graduate Program in Art History University of California, Riverside, June 2016 Dr. -

Photographic Periodicals A-D ART CAHAN LITERATURE BOOKSELLER, LTD AMERICANA

ANDREW Elist 34: Photographic PeriodicalsPHOTOGRAPHY A-D 1 Elist 34: Photographic Periodicals A-D ART CAHAN LITERATURE BOOKSELLER, LTD AMERICANA Terms: All items are offered subject to prior sale. A phone call, email or fax insures availability. Shipping and insurance charges are additional. Returns are accepted for any reason within ten days of receipt; we request notification in advance. All items must be returned in the exact condition in which they were received. Library and Institutional billing requirements will be accommodated. Customers new to us are requested to send payment in advance or provide references. For your convenience we also accept payment by Visa, MasterCard, American Express, and PayPal. Ohio customers will be charged the applicable sale tax. Overseas customers please note: all items will be shipped via insured priority airmail unless otherwise requested. A statement will be sent under separate cover and we request payment in full upon receipt. We accept payment by bank transfer, a check drawn upon a U.S. bank in dollars, or via credit card. This list represents just a small portion of our stock. If there are specific items you are seeking, we would be pleased to receive your desiderata. We hope you will keep in mind that we are always pleased to consider fine individual items or entire collections for purchase. To receive our future E-Lists and other notifications, please send us your email address so we can let you know when a new list is available at our website, cahanbooks.com. PO Box 5403 • Akron, OH 44334 • 330.252.0100 Tel/Fax [email protected] • www.cahanbooks.com 1. -

Jun 1 4 2007

An Eye for Vulgarity: How MoMA Saw Color Through Wild Bill's Lens by Anna K.arrer I<ivlan B.A. Art History University of San Diego SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF l\RCHITECTURE IN Pl\RTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIRE1\IENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF 1\1ASTEROF SCIENCE IN .ARCHITECTURE STUDIES ~\TTHE MASSACHUSETfS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY JUNE 2007 @2007 lvlassachusetts Institute of Technology. All rights reserved. Signature of Author: ( /- Department of Architecture l\Iay 24, 2007 1\ Certified by: \.._ A"---.. 't - \. Erika N aginski Associate Professor of the History of Art Thesis supervisor Accepted by: \I ~ ~ Julian Bein~rt Professor of i\rchitecture Chairman, Departn1ent Committee on Graduate Students MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY JUN 1 4 2007 i LIBRARIES .-----.--- - -__ -l Thesis Readers: Caroline A. Jones Associate Professor of the History of Art History, Theory, and Criticism of Architecture and Art program Department of Architecture ~fassachusetts Institute of Technology ~Iark Jarzombek Professor of the History of Architecture Director of the History, Theory, and Criticism of Architecture and Art program Department of Architecture ~Iassachusetts Institute of Technology 2 An Eye for Vulgarity: How MaMA Saw Color Through Wild Bill's Lens by Anna I(arrer I<ivlan Submitted to the Department of Architecture on May 25, 2007 in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Architecture Studies at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology ABSTRACT This thesis is an examination of the 1976 Museum of Modern Art exhibition of color photographs by William Eggleston-the second one-man show of color photography in the museum's history- with particular attention to the exhibition monograph, lf7illiam Egglestol1:r Guide. -

Criticizing Photographs: an Introduction to Understanding Images

PPStijj^ • as ••"• <•'. " ..•.••. '••••.:: V; . Criticizing Photographs /\n iiiLiuu-ULLion LU unutisianQing linages Third Edition Terry Barrett Criticizing Photographs An Introduction to Understanding Images THIRD EDITION Terry Barrett The Ohio State University Boston Burr Ridge, IL Dubuque, IA Madison, Wl New York San Francisco St. Louis Bangkok Bogota Caracas Kuala Lumpur Lisbon London Madrid Mexico City Milan Montreal New Delhi Santiago Seoul Singapore Sydney Taipei Toronto McGraw-Hill Higher Education eg A Division of The McGraw-Hill Companies Criticizing Photographs: An Introduction to Understanding Images Published by McGraw-Hill, an imprint of The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. 1221 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY, 10020. Copyright © 2000, 1996, 1990 by The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or distributed in any form or by any means, or stored in a database or retrieval system, without the prior written consent of The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc., including, but not limited to, in any network or other electronic storage or transmission, or broadcast for distance learning. Some ancillaries, including electronic and print components, may not be available to customers outside the United States. This book is printed on acid-free paper. 9 10 11 12 DOC/DOC 9 8 7 6 5 ISBN 0-7674-1186-2 Sponsoring editor, Janet M. Beatty; production editor, Melissa Williams Kreischer: manuscript editor, Joan Pendleton; design manager, Jean Mailander; text and cover designer, Amy Evans McClure; cover art, © William Wegman, Ocean View, 1997, 20" X 24" Polaroid; manu facturing manager, Randy Hurst. The text was set in 10/13 Berkeley Oldstyle Medium by TBH Typecast, Inc.