The Americans Unit 6

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter 29 Section 3 Conflicts at Home

Chapter 29 Section 3 Conflicts at Home One American’s Story A student journalist took Mary Ann Vecchio’s picture as she knelt by a dead student at Kent State University in Ohio. The dead youth was Jeffrey Glenn Miller, one of four students killed by the National Guard during an antiwar demonstration on May 4, 1970. Later, Vecchio said PRIMARY SOURCE “I couldn’t believe that people would kill . just because he demonstrated against the Vietnam War.” —Mary Ann Vecchio Gillum, conference at Emerson College, April 23, 1995 Mary Ann Vecchio was just 14 when she became a symbol of anguish over the Vietnam War. Growing opposition to the war led to deep divisions in American society. The Growing Antiwar Movement KEY QUESTION Why did so many Americans oppose the war? As the war escalated in the mid-1960s, antiwar feeling grew among Americans at home. Religious leaders, civil rights leaders, teachers, students, journalists, and others opposed the war for a variety of reasons. Protests Grow Some protestors believed that the United States had no business involving itself in another country’s civil war. Others believed that the methods of fighting the war were immoral. Still others thought that the costs to American society were too high. College students formed a large and vocal group of protesters. Many opposed the draft, which required young men to serve in the military. In protests nationwide, young men burned their draft cards. About 50,000 people staged such a protest in front of the Pentagon on October 21, 1967. Opponents of the draft pointed out its unfairness. -

May 4, 2014, Kent State Killings

KENT STATE KILLINGS MAY 4, 1970 Compiled by Dick Bennett for the OMNI Center for Peace, Justice, and Ecology, in Remembrance. Contents “Ohio” Google Search, May 4, 2014 44th Anniversary Google Search, May 4, 2014 “I Want to Remember” by Sidney Burris, May 4, 2013 2014, 44th Anniversary of Kent State Shootings Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young – “Ohio”, Google Search, May 4, 2014 • Ohio (Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young song) - Wikipedia, the ... en.wikipedia.org/.../Ohio_(Crosby,_Stills,_Nash_%26_Young... Wikipedia "Ohio" is a protest song and counterculture anthem written and composed by NeilYoung in reaction to the Kent State shootings of May 4, 1970, and performed ... Recording - Lyrics and reaction - Covers - Personnel • APUS Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young - Ohio (Lyric Video ... ► 2:59► 2:59 www.youtube.com/watch?v... YouTube Jun 4, 2013 - Uploaded by Grace Naef APUS Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young - Ohio (Lyric Video) - YouTube. Subscribe 19. All comments (49 ... • Crosby Stills Nash & Young - Ohio - (live audio 1970 ... ► 3:51► 3:51ww.youtube.com/watch?v=a6irfBMm48g YouTube Feb 22, 2010 - Uploaded by ElvinCole Wikipedia: Young wrote the lyrics to "Ohio" after seeing the photos of the incident in Life Magazine. On the ... • Neil Young Ohio Lyric Analysis - Thrasher's Wheat thrasherswheat.org/fot/ohio.htm Analysis of the lyrics of Crosby, Stills, Nash, and Young song "Ohio" ... Lasho interprets the meaning of the lyrics to Neil Young's song "Ohio" and offers an .. MAY 4, 1970 KENT STATE SHOOTINGS, Google Search, May 4, 2014 1. Kent State shootings - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kent_State_shootings Wikipedia The Kent State shootings (also known as the May 4 massacre or the Kent State massacre) occurred at Kent State University in the US city of Kent, Ohio, and .. -

The Historical and Cultural Meanings of American Music Lyrics from the Vietnam War

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 5-2013 The historical and cultural meanings of American music lyrics from the Vietnam War. Erin Ruth McCoy University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Recommended Citation McCoy, Erin Ruth, "The historical and cultural meanings of American music lyrics from the Vietnam War." (2013). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 940. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/940 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE HISTORICAL AND CULTURAL MEANINGS OF AMERICAN MUSIC LYRICS FROM THE VIETNAM WAR By Erin Ruth McCoy B.A., Wingate University, 2003 M.A., Clemson University, 2007 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of the University of Louisville In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Humanities University of Louisville Louisville, KY May 2013 Copyright 2013 by Erin R. McCoy All Rights Reserved THE HISTORICAL AND CULTURAL MEANINGS OF AMERICAN MUSIC LYRICS FROM THE VIENTAM WAR By Erin Ruth McCoy B.A., Wingate University, 2003 M.A., Clemson University, 2007 A Dissertation Approved on April 5, 2013 by the following Dissertation Committee: _______________________________________________________ Dr. -

Telling Their Own Story: How Student Newspapers Reported Campus Unrest, 1962-1970 Kaylene Dial Armstrong University of Southern Mississippi

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Aquila Digital Community The University of Southern Mississippi The Aquila Digital Community Dissertations Summer 8-2013 Telling Their Own Story: How Student Newspapers Reported Campus Unrest, 1962-1970 Kaylene Dial Armstrong University of Southern Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations Part of the Civic and Community Engagement Commons, Other American Studies Commons, and the Peace and Conflict Studies Commons Recommended Citation Armstrong, Kaylene Dial, "Telling Their Own Story: How Student Newspapers Reported Campus Unrest, 1962-1970" (2013). Dissertations. 156. https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations/156 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by The Aquila Digital Community. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of The Aquila Digital Community. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The University of Southern Mississippi TELLING THEIR OWN STORY: HOW STUDENT NEWSPAPERS REPORTED CAMPUS UNREST, 1962-1970 by Kaylene Dial Armstrong Abstract of a Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School of The University of Southern Mississippi in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy August 2013 ABSTRACT TELLING THEIR OWN STORY: HOW STUDENT NEWSPAPERS REPORTED CAMPUS UNREST, 1962-1970 by Kaylene Dial Armstrong August 2013 The work of student journalists often appears as a source in the footnotes when researchers tell the story of perhaps the most significant period in the history of higher education in the United States – the student protest era throughout the 1960s and early 1970s. -

VVMF Education Guide

FOUNDERS OF THE WALL ECHOES FROM THE WALL Wars usually take place far from American soil in places that few Americans understand. Americans are thus dependent on others, such as the government, the news media, and the entertainment industry, to help them understand why the nation is at war, the progress of the war, and the outcomes and implications. IN THE CLASSROOM DISCUSSION GUIDE This lesson plan will involve a review of how information on war has been The Media and War reported over the course of the 20th Americans rely heavily on the news media for information about the How do Americans century. Students will analyze and nation’s wars. Begin by asking students what they believe to be the role of the media in society: Is it to keep citizens informed? Is it to tell the truth at any cost? Is it to influence Understand the Wars debate the validity of information change? Is it to confirm what we already believe? Can it play several roles at once? coming from different news sources, Across much of American history, the U.S. government exercised little control over the from Vietnam to today, and discuss ability of the news media to report on military operations. But during the First and Their Nation Fights? Second World Wars, the United States placed new restrictions on the flow of information. the role of a free press. During the Second World War, for example, the newly established Office of Censorship circulated a “Code of Wartime Practices for the American Press,” which prohibited journalists from reporting any information – everything from details about troop movements to weather reports to industrial production figures – that might have value to the enemy. -

Kent State in Context: the National Guard in Campus Disorders 1965 - 1970 Thomas M

Presented at the 2020 Virtual Meeting of the American Sociological Association August 10, 2020 Kent State in Context: The National Guard in Campus Disorders 1965 - 1970 Thomas M. Guterbock Department of Sociology University of Virginia “National Guard personnel walking toward crowd near Taylor Hall, tear gas has been fired,” 2 Kent State University Libraries. Special Collections and Archives, accessed July 21, 2020, https://omeka.library.kent.edu/special-collections/items/show/1426. Overview • Purpose • Methods, background of the paper • Types of protest and appropriate control strategies • About the U. S. National Guard • Importance of location (lack of local police) • History of NG involvement on college campuses, 1965-1970 – 44 incidents, 3 stages • Escalation, state political factors • Analyzing NG success and misapplication of force – As related to type of protest, enforcement code • Discussion and conclusions . – About the National Guard – About Kent State 3 4 Teenager Mary Ann Vecchio screams as she kneels over the body of Kent State University student Jeffrey Miller, May 4, 1970. Photo by John Filo. 5 Purpose • On May 4, 1970, Ohio National Guard troops shot their rifles at a crowd of protesting students, killing four and wounding seven. – A pivotal moment in the movement against the Vietnam War • The Scranton Commission (1970) called the shootings “unnecessary, unwarranted, and inexcusable.” – But the event was not inexplicable. • Analysis: every incident of campus unrest where NG was actively involved, 1965 - 70. • Purpose: Identify factors that contributed to: – NG effectiveness in restoring/maintaining order – Violence/misapplication force by NG • Analysis not meant to exonerate those who acted badly at Kent State 6 Background and methods • Author enlisted in DC National Guard in late 1969, under threat of draft – Applied to U. -

Photography As Social Conscience Wc 3338

Photography as Social Conscience wc 3338 In almost 200 years since the invention of photography there have been many photographers who have used their camera to draw attention to aspects of society which are unjust, shameful, discriminatory or harmful to the health and happiness of certain groups of people. They have used their art to expose horrors prevalent in areas including, for example, child labour and child neglect, homelessness, degrading poverty, hazardous working conditions, environmental pollution, war crimes and other crimes against humanity… the list is a very long one. This kind of photography is part of documentary photography and is often ¾ but not always ¾ the mission of photojournalists. Whatever the subject of such photos, they were always shocking and appalling. For example, I can remember the horror I felt when I first saw the photo Tomoko Uemura in her Bath by the famous Magnum/Life Magazine photographer, W. Eugene Smith. First published in 1971, it shows Toko’s mother bathing her daughter who was born blind, deaf and deformed as were many others in the small fishing village of Minamata after a chemical company dumped mercury into the local water supply. W. Eugene Smith: "Tomoko Uemura in her Bath," 1971. Life Magazine and especially the Magnum photographers whose photos were published in it, brought to its readers images to prick the social conscience long before TV and programs like 4 Corners existed to expose the iniquities and injustices of our world. To take another, pre-TV example, here is a photo by the woman who was described by other photographers as “always in the right place at the right time”… Margaret Bourke-White. -

The Blue Marble Gregory a Petsko*

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by PubMed Central Petsko Genome Biology 2011, 12:112 http://genomebiology.com/2011/12/4/112 COMMENT The blue marble Gregory A Petsko* It is one of the most iconic images - not just of our time, but of all time. The picture of the earth as seen from 28,000 miles (45,000 km) out in space - often called ‘the blue marble’ because it resembles the spherical agates we used to play with as children - was taken on 7 December 1972 by the crew of the spacecraft Apollo 17 (it is reproduced here). The Arabian Peninsula is clearly visible at the top, with the east coast of Africa extending down towards Antarctica, the white mass at the bottom. (The original picture was actually upside down from this view, but the picture is usually presented rotated as it is here.) For those who care about such things, the photo was taken with a 70 mm Hasselblad camera with an 80 mm lens. Apollo 17 was the last manned lunar mission, so no human beings have since been far enough out into space to take another picture that shows the whole globe. Because of the National Aeronautics and Space Adminis- tration’s (NASA’s) insistence on de-emphasizing the role of any one crew member in space missions, the photo- graph is credited to the entire flight team: Eugene The blue marble. Photographed by Eugene Cernan, Ronald Evans Cernan, Ronald Evans and Jack Schmit. It is still not and Jack Schmit. -

South Main Street Building Is Sold

Tuesday September 26, 2017 Today Wednesday Thursday 89/66 84/67 71/56 Mostly Partly Partly WHEREA BIGGER NEWSPAPER MEANS MORE LOCAL NEWS | JOURNAL-NEWS.COM sunny cloudy cloudy Full Northern Cincinnati forecast: C4 $2.00 LOCAL& STATE, B1 LOCAL& STATE, B1 LOCAL& STATE, B1 MIDDLETOWN APPROVES MIAMIUNIVERSITYSEXUAL BUTLER MAKES$10M ADDITIONALPOLICEOFFICER ASSAULTSINVESTIGATED COMMUNICATIONS DEAL MIDDLETOWN FOCUS ON LOCAL ECONOMY Ohio, Ky. to compete for UPS jobs State tax credit OK’d for Monday approved a 1.5 percent, company as it considers 7-year tax credit to UPS for the creation of $5.5 million in new site in Butler County. annual payroll as a result of a new planned location project ByThomas Gnau in West Chester, the state said. Staff Writer The company does not list an address for the proposed West UPS Supply Chain Solutions Chester location. is considering the creation of As part of the tax credit agree- 130 new full-time jobs in But- ment, the authority requires UPS ler County’s West Chester Twp. to maintain operations at the by the year 2020, state officials proposed location for at least said Monday. a decade. The building that houses a homeless shelter and barber shop on South Main Street in Middletown has But the project could also go “UPS is considering placing been sold, according to Realtor Rachel Lewitt. CONTRIBUTED to a UPS location in Louisville, this expansion at its Louisville Ky., an Ohio development depart- hub where they can continue to ment warned. The Ohio Tax Credit Authority UPS jobs continued on A5 South Main Street FOCUS ON BUSINESS Cincy airport sets building is sold new traffic records Middletown homeless 32 and 34 S. -

Eclipse Over America Helping Our People Helping People It’S a Guiding Principle at Silver State Schools Credit Community Union

Trusted. Valued. Essential. AUGUST 2017 NOVA: Eclipse Over America Helping Our People Helping People It’s a guiding principle at Silver State Schools Credit Community Union. Since 1951, we have been fully-vested in the Southern Nevada community we serve. Whether it’s setting up your child’s first savings account, finding a Through Life’s great rate on a loan, buying your first home or finding the best investment, our employees are available to Financial Journey put your best interests first. Become a member today and experience the SSSCU difference. 800.357.9654 silverstatecu.com Vegas PBS A Message from the Management Team General Manager General Manager Tom Axtell, Vegas PBS Educational Media Services Director Niki Bates Production Services Director Kareem Hatcher Communications and Brand Management Director Shauna Lemieux Business Manager Brandon Merrill Engineering, IT & Emergency Response Director George Molnar From Sputnik to the Solar Eclipse Content Director ixty years ago, the Soviet Union launched the world's first artificial satel- Cyndy Robbins lite, ushering in a new era of scientific discovery. Sputnik I was an impres- Workforce Training & Economic Development Director Debra Solt sive technological advancement that also triggered anxiety and fear over a Corporate Partnerships Director perceived technology gap between the United States and the Soviet Union. Bruce Spotleson SIn response, President Eisenhower convinced Congress to pass the National Defense Southern Nevada Public Television Board of Directors Education Act (NDEA) less than one year later, providing the funding that fueled the Executive Director space race and eventually landed the first human on the moon.The NDEA also includ- Tom Axtell, Vegas PBS ed funding to increase science and technology education, foreign language, and world President Bill Curran, Ballard Spahr, LLP history and culture courses as a vital component of our national security and econom- Vice President ic competitiveness. -

When Abbie Met Jerry”)

I Adult Ed January 23rd, 2011 Jewish Radicalism of the Sixties (Or “When Abbie Met Jerry”) Welcome to the JCS Adult Education, our first class of the 2011 – 2012 year. Our discussion today will focus on Jewish radicalism in general and in particular as a force for social change during the decade of the 1960s. I usually begin these discussions by explaining the relevance of the topic to be discussed or what I like to call the “Why you should care” portion. Jewish radicalism is a part of our cultural legacy. I often liken Jewish culture to a tapestry. If you start removing threads, the whole thing is diminished. No one is born a radical. You become one when you are confronted with a situation or circumstance that offends your moral values. That depends on what each person values. Moreover, the individual‟s response has to be so great as to overcome their obedience to authority. Let me illustrate this with the stories of two men, each of whom would become famous. Our first story is about a young man, not Jewish, whose life-changing moment occurred at Forward Base Hammer in Iraq in 2009. While he works in the military intelligence section, his job is hardly exciting. In fact it is really boring. He describes it as follows: “You had people working fourteen hours a day, every single day, no weekends, no recreation. Everyone just sat at their workstation watching music videos, car chases, buildings exploding and writing more stuff to CD/DVD.”1 Then one day this young man comes across a video, filmed from the camera in the nose of an Apache helicopter, showing the events that took place on the morning of July 12th, 2007. -

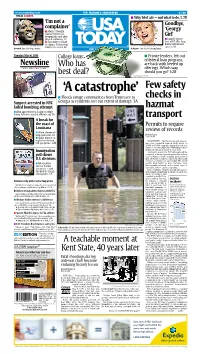

'A Catastrophe'

www.usatoday.com THE NATION’S NEWSPAPER $1.00 FINAL. SCORES mWhy ‘Idol’ ails — and what to do, 1, 7D ‘I’m not a Goodbye, complainer’ mMagic’s Dwight ‘Georgy Howard works on keeping his cool after Girl’ playoff outbursts, 1C mLynn Redgrave mSuns take 1- 0 lead dies at 67 after long battle with breast By Nell Redmond, AP vs. Spurs; Celtics rout 1999 photo by Bob Riha Jr., USA TODAY Cavs to tie series, 6C cancer, 3D Howard: Fined for blog remarks. NO. 1INTHE USA Redgrave: Part of noted acting family. Tuesday, May4, 2010 c mPrivate lenders, left out College loans: of federal loan program, Newsline Who has are back with beefed up n News n Money n Sports n Life offerings. Which way best deal? should you go? 1-2B By Sam Ward, USA TODAY ‘A catastrophe’ Few safety Surveillance video image; NYPD via AP mFloods ravage communities from Tennessee to checks in Suspect arrested in NYC Georgia as residents sort out extent of damage, 3A failed bombing attempt hazmat mMan apprehended at airport while trying to leave country, officials say, 5A transport AbreaK for the coast of Permits to require Louisiana review of records mWind, chemicals help rein in oil, 3A By Peter Eisler mSpill’s impact on USA TODAY region’s economy, WASHINGTON — The Department of Transporta- U.S. gas prices, 1-2B tion never conducted required safety checks on By Eric Gay, AP 20,000 to 30,000 companies that got special per- mits to move risky shipments of hazardous materi- als by road, rail, water and air, records show.