A Study of Selected Fiction by Indian W Om En N Ovelists in English

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dus Kahaniyaan Free Moviesl

Dus Kahaniyaan Free Moviesl 1 / 4 Dus Kahaniyaan Free Moviesl 2 / 4 3 / 4 MOVIE NAME: DUS KAHANIYAAN (BOLLYWOOD MOVIE WATCH ONLINE) (PDVD-RIP) PRESENTER: Sanjay Dutt BANNER: White Feather .... Stream & watch back to back Full Movies only on Eros Now - https://goo.gl/GfuYux Ten short stories, across .... Dus Kahaniyaan (2007). Original Title: दस कहानियाँ. Watch Now. Filters. Best Price. SD. HD. 4K. Stream. Jio Cinema. Subs. Zee5. Free. Eros Now. Subs HD.. In every web site they charging for full movie.. I am not going to pay.. So plz any body send me the link of this movie where it is downloaded for free of cost.. Watch Dus Kahaniyaan - title on DIRECTV. It's available to watch.. Dus Kahaniyaan - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Official Movie Poster of Dus Kahaniyaan: Produced by: Sanjay Gupta: Starring: Sanjay Dutt .... Dus Kahaniyaan - Bollywood>Bollywood (1954 - 2008) - watch hd movie newly available worth watching .... Up next. 50+ videos Mix - Dus Kahaniyaan Full Hindi Movie 2007YouTube. Out of Time YouTube Movies .... Dus Kahaniyaan is only available for rent or buy starting at $5.99. Get notified if it ... all in one place. Totally free to use! ... on Prime Video. It's an action & adventure and crime movie with an average IMDb audience rating of 5.7 (1,460 votes).. Dus Kahaniyaan. Dus Kahaniyaan movie poster ... This film is a collection of ten stories of kind strangers who are living an oppression free life.. Dus Kahaniyaan ( transl. Ten stories) is a 2007 Indian Hindi- language anthology film ... From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. -

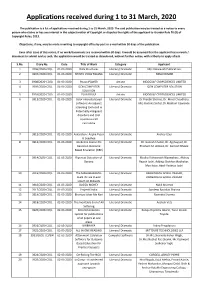

Applications Received During 1 to 31 March, 2020

Applications received during 1 to 31 March, 2020 The publication is a list of applications received during 1 to 31 March, 2020. The said publication may be treated as a notice to every person who claims or has any interest in the subject matter of Copyright or disputes the rights of the applicant to it under Rule 70 (9) of Copyright Rules, 2013. Objections, if any, may be made in writing to copyright office by post or e-mail within 30 days of the publication. Even after issue of this notice, if no work/documents are received within 30 days, it would be assumed that the applicant has no work / document to submit and as such, the application would be treated as abandoned, without further notice, with a liberty to apply afresh. S.No. Diary No. Date Title of Work Category Applicant 1 3906/2020-CO/L 01-03-2020 Data Structures Literary/ Dramatic M/s Amaravati Publications 2 3907/2020-CO/L 01-03-2020 SHISHU VIKAS YOJANA Literary/ Dramatic NIRAJ KUMAR 3 3908/2020-CO/A 01-03-2020 Picaso POWER Artistic INDOGULF CROPSCIENCES LIMITED 4 3909/2020-CO/L 01-03-2020 ICON COMPUTER Literary/ Dramatic ICON COMPUTER SOLUTION SOLUTION 5 3910/2020-CO/A 01-03-2020 PLANOGULF Artistic INDOGULF CROPSCIENCES LIMITED 6 3911/2020-CO/L 01-03-2020 Color intensity based Literary/ Dramatic Dr.Preethi Sharma, Dr. Minal Chaudhary, software: An adjunct Mrs.Ruchika Sinhal, Dr.Madhuri Gawande screening tool used in Potentially malignant disorders and Oral squamous cell carcinoma 7 3912/2020-CO/L 01-03-2020 Aakarshan : Aapke Pyaar Literary/ Dramatic Akshay Gaur ki Seedhee 8 3913/2020-CO/L 01-03-2020 Academic course file Literary/ Dramatic Dr. -

Dossier-De-Presse-L-Ombrelle-Bleue

Splendor Films présente Synopsis Dans un petit village situé dans les montagnes de l’Himalaya, une jeune fille, Biniya, accepte d’échanger son porte bonheur contre une magnifique ombrelle bleue d’une touriste japonaise. Ne quittant plus l’ombrelle, l’objet L’Ombrelle semble lui porter bonheur, et attire les convoitises des villageois, en particulier celles de Nandu, le restaurateur du village, pingre et coléreux. Il veut à tout prix la récupérer, mais un jour, l’ombrelle disparaît, et Biniya bleue mène son enquête... Note de production un film de Vishal Bhardwaj L’Ombrelle bleue est une adaptation cinématographique très fidèle à la nouvelle éponyme de Ruskin Bond. Le film a été tourné dans la région de l’Himachal Pradesh, située au nord de l’Inde, à la frontière de la Chine et Inde – 2005 – 94 min – VOSTFR du Pakistan, dans une région montagneuse. La chaîne de l’Himalaya est d’ailleurs le décor principal du film, le village est situé à flanc de montagne. Inédit en France L’Ombrelle bleue reprend certains codes et conventions des films de Bollywood. C’est pourtant un film original dans le traitement de l’histoire. Alors que la plupart des films de Bollywood durent près de trois heures et traitent pour la plupart d’histoires sentimentales compliquées par la religion et les obligations familiales, L’Ombrelle bleue s’intéresse davantage aux caractères de ses personnages et à la nature environnante. AU CINÉMA Le film, sorti en août 2007 en Inde, s’adresse aux enfants, et a pour LE 16 DÉCEMBRE vedettes Pankaj Kapur et Shreya Sharma. -

Toba Tek Singh Short Stories (Ii) the Dog of Tithwal

Black Ice Software LLC Demo version WELCOME MESSAGE Welcome to PG English Semester IV! The basic objective of this course, that is, 415 is to familiarize the learners with literary achievements of some of the significant Indian Writers whose works are available in English Translation. The course acquaints you with modern movements in Indian thought to appreciate the treatment of different themes and styles in the genres of short story, fiction, poetry and drama as reflected in the prescribed translations. You are advised to consult the books in the library for preparation of Internal Assessment Assignments and preparation for semester end examination. Wish you good luck and success! Prof. Anupama Vohra PG English Coordinator 1 Black Ice Software LLC Demo version 2 Black Ice Software LLC Demo version SYLLABUS M.A. ENGLISH Course Code : ENG 415 Duration of Examination : 3 Hrs Title : Indian Writing in English Total Marks : 100 Translation Theory Examination : 80 Interal Assessment : 20 Objective : The basic objective of this course is to familiarize the students with literary achievement of some of the significant Indian Writers whose works are available in English Translation. The course acquaints the students with modern movements in Indian thought to compare the treatment of different themes and styles in the genres of short story, fiction, poetry and drama as reflected in the prescribed translations. UNIT - I Premchand Nirmala UNIT - II Saadat Hasan Manto, (i) Toba Tek Singh Short Stories (ii) The Dog of Tithwal (iii) The Price of Freedom UNIT III Amrita Pritam The Revenue Stamp: An Autobiography 3 Black Ice Software LLC Demo version UNIT IV Mohan Rakesh Half way House UNIT V Gulzar (i) Amaltas (ii) Distance (iii)Have You Seen The Soul (iv)Seasons (v) The Heart Seeks Mode of Examination The Paper will be divided into section A, B and C. -

EROS INTERNATIONAL COLLECTION of INDIAN CINEMA on DVD Last Update: 2008-05-21 Collection 26

EROS INTERNATIONAL COLLECTION OF INDIAN CINEMA ON DVD Last Update: 2008-05-21 Collection 26 DVDs grouped by year of original theatrical release Request Titles by Study Copy No. YEAR OF THEATRICAL COLOR / RUNNING STUDY COPY NO. CODE FILM TITLE RELEASE B&W TIME GENRE DIRECTOR(S) CAST 1 DVD5768 M DVD-E-079 MOTHER INDIA 1957 color 2:43:00 Drama Mehoob Khan Nargis, Sunil Dutt, Raj Kumar 2 DVD5797 M DVD-E-751 KAAGAZ KE PHOOL 1959 color 2:23:00 Romance Guru Dutt Guru Dutt, Waheeda Rehman, Johnny Walker 3 DVD5765 M DVD-E-1060 MUGHAL-E-AZAM 1960, 2004 color 2:57:00 Epic K. Asif Zulfi Syed, Yash Pandit, Priya, re-release Samiksha 3.1 DVD5766 M DVD-E-1060 MUGHAL-E-AZAM bonus material: premier color in Mumbai; interviews; "A classic redesigned;" deleted scene & song 4 DVD5815 M DVD-E-392 CHAUDHVIN KA CHAND 1960 b&w 2:35:00 Romance M. Sadiq Guru Dutt, Waheeda Rehman, Rehman 5 DVD5825 M DVD-E-187 SAHIB BIBI AUR GHULAM 1962 b&w 2:42:00 Drama Abrar Alvi Guru Dutt, Meena Kuman, Waheeda Rehman 6 DVD5772 M DVD-E-066 SEETA AUR GEETA 1972 color 2:39:00 Drama Ramesh Sippy Dharmendra, Sanjeev Kumar, Hema Malini 7 DVD5784 M DVD-E-026 DEEWAAR 1975 color 2:40:00 Drama Yash Chopra Amitabh Bachchan, Shashi Kapoor, Parveen Babi, Neetu Singh 8 DVD5788 M DVD-E-016 SHOLAY 1975 color 3:24:00 Action Ramesh Sippy Amitabh Bachchan, Dharmendra, Sanjeev Kumar, Hema Malini 9 DVD5807 M DVD-E-256 HERA PHERI 1976 color 2:37:00 Comedy Prakash Mehra Amitabh Bachchan, Vinod Khanna, Saira Banu, Sulakshana Pandit 10 DVD5802 M DVD-E-140 KHOON PASINA 1977 color 2:31:00 Drama Rakesh Kumar Amitabh Bachchan, Vinod Khanna, Rekha 11 DVD5816 M DVD-E-845 DON 1978 color 2:40:00 Action Chandra Barot Amitabh Bachchan, Zeenat Aman, Pran 12 DVD5811 M DVD-E-024 MR. -

Breaking in / out of Bollywood

Breaking in / out of Bollywood : stratégies et trajectoires des productions et personas du nouveau cinéma de l’industrie du film de Mumbai depuis l’arrivée du multiplexe Catherine Bernier Thèse présentée à l’école de cinéma Mel Hoppenheim comme exigence partielle au grade de Philosophae doctor (Ph.D.) Université Concordia Montréal, Québec, Canada Mai 2018 © Catherine Bernier, 2018 CONCORDIA UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES This is to certify that the thesis prepared By: Catherine Bernier Entitled: Breaking in/out of Bollywood: stratégies et trajectoires des productions et personas du nouveau cinéma de l’industrie du film de Mumbai depuis l’arrivée du multiplexe and submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor Of Philosophy (Film and Moving Image Studies) complies with the regulations of the University and meets the accepted standards with respect to originality and quality. Signed by the final examining committee: Chair Dr. Daniel Salée External Examiner Dr. Bernard Bernier External to Program Dr. Rachel Berger Examiner Dr. Charles Acland Examiner Dr. Marc Steinberg Thesis Supervisor Dr. Thomas Waugh Approved by Dr. Martin Lefebvre, Graduate Program Director Thursday, June 14, 2018 Dr. Rebecca Taylor Duclos, Dean Faculty of Fine Arts Résumé Breaking in / out of Bollywood : stratégies et trajectoires des productions et personas du nouveau cinéma de l’industrie du film de Mumbai depuis l’arrivée du multiplexe Catherine Bernier, Ph.D. Université Concordia, 2018 Cette thèse documente l’émergence d’un nouveau cinéma à Mumbai qui défie les conventions ayant traditionnellement contribué à distinguer le cinéma populaire et parallèle dans le contexte indien. -

Sindhi's in Film Industry

in Sindhi’sFilm Industry By Deepak Ramchandani This is the inventory of Sindhi People in Film Deepak Ramchandani industry which include www.ramchandanidays. Indian Cinema, television wordpress.com E m a i l - and in foreign films deepakgr2007@rediffmail . c o m 1 0 / 1 / 2 0 1 3 Prephase: A CD was presented to me by my Sister and Brother-in-Law which contained about 800 songs, I had copied in my mobile and from some months these songs had became part of my life, especially I here Master Chandur daily. One of the song “ Wafaia Ja Putla Wafadar Sindhi, Hu Hara Fanna Me Ahin Hoshiyar Sindhi” In this song Master Chander narrated the name of Gope Kamlani, comedian actor in Hindi Film industry for which I was not knowning. One one day I along with my wife Asha attended a program in Sindhology Adipur in which music on voilen was performed by Master Kanayalal Lalwani, he had worked along with many music director and it was also told that his children are also working for music in film industry. These facts were unknown to me and also to many Sindhis. Most often while watching television ,my wife Asha, son Yash and daughter Sonam discussed about who is sindhi artist in film and television industry. These event brought a thought in my mind to list the Sindhis who are working in film industry, hence I started searching on web. I hoped that I could collect more than 100 names but this figure reached more than 350 numbers which are listed and detailed in this collection. -

DIRECTORS: Satyajit Ray Satyajit Ray Directed 36 Films, Including

DIRECTORS: Satyajit Ray Satyajit Ray directed 36 films, including feature films, documentaries and shorts.. Ray received many major awards in his career, including 32 Indian National Film Awards, a number of awards at international film festivals and award ceremonies, and an honorary Academy Award in 1992. Satyajit Ray's films are both cinematic and literary at the same time; using a simple narrative, usually in a classical format, but greatly detailed and operating at many levels of interpretation. His first film, Pather Panchali (Song of the little road, 1955) established his reputation as a major film director, winning numerous awards including Best Human Document, Cannes, 1956 and Best Film, Vancouver, 1958. It is the first film of a trilogy - The Apu Trilogy - a three-part tale of a boy's life from birth through manhood. The other two films of this trilogy are Aparajito (The Unvanquished, 1956) and Apur Sansar (The World of Apu, 1959). His later films include Jalsaghar (The Music Room, 1958), Devi (The Goddess, 1960), Teen Kanya (Two Daughters, 1961),Charulata (The Lonely Wife, 1964), Nayak (The Hero, 1966), Asani Sanket (Distant Thunder, 1973), Shatranj Ke Khilari(The Chess Players, 1977), Ghare Baire (The Home and the World, 1984), Ganashatru (An Enemy Of The People, 1989) and Shakha Prashakha (Branches Of The Tree, 1991). Agantuk (The Stranger, 1991) was his last film. Mahesh Bhatt Mahesh Bhatt is a prominent Indian film director, producer and screenwriter. Bhatt's early directional career consisted of acclaimed movies, such as Arth, Saaransh, Janam, Naam, Sadak and Zakhm. He was later the writer of numerous commercial films in a range of genres, from dramas like Hum Hain Rahi Pyar Ke and comedies like Duplicate, though he was mostly recognised for thrillers like Inteha, Jism, Murder and Woh Lamhe. -

Crime Thriller Cluster 1

Crime Thriller Cluster 1 movie cluster 1 1971 Chhoti Bahu 1 2 1971 Patanga 1 3 1971 Pyar Ki Kahani 1 4 1972 Amar Prem 1 5 1972 Ek Bechara 1 6 1974 Chowkidar 1 7 1982 Anokha Bandhan 1 8 1982 Namak Halaal 1 9 1984 Utsav 1 10 1985 Mera Saathi 1 11 1986 Swati 1 12 1990 Swarg 1 13 1992 Mere Sajana Saath Nibhana 1 14 1996 Majhdhaar 1 15 1999 Pyaar Koi Khel Nahin 1 16 2006 Neenello Naanalle 1 17 2009 Parayan Marannathu 1 18 2011 Ven Shankhu Pol 1 19 1958 Bommai Kalyanam 1 20 2007 Manase Mounama 1 21 2011 Seedan 1 22 2011 Aayiram Vilakku 1 23 2012 Sundarapandian 1 24 1949 Jeevitham 1 25 1952 Prema 1 26 1954 Aggi Ramudu 1 27 1954 Iddaru Pellalu 1 28 1954 Parivartana 1 29 1955 Ardhangi 1 30 1955 Cherapakura Chedevu 1 31 1955 Rojulu Marayi 1 32 1955 Santosham 1 33 1956 Bhale Ramudu 1 34 1956 Charana Daasi 1 35 1956 Chintamani 1 36 1957 Aalu Magalu 1 37 1957 Thodi Kodallu 1 38 1958 Raja Nandini 1 39 1959 Illarikam 1 40 1959 Mangalya Balam 1 41 1960 Annapurna 1 42 1960 Nammina Bantu 1 43 1960 Shanthi Nivasam 1 44 1961 Bharya Bhartalu 1 45 1961 Iddaru Mitrulu 1 46 1961 Taxi Ramudu 1 47 1962 Aradhana 1 48 1962 Gaali Medalu 1 49 1962 Gundamma Katha 1 50 1962 Kula Gotralu 1 51 1962 Rakta Sambandham 1 52 1962 Siri Sampadalu 1 53 1962 Tiger Ramudu 1 54 1963 Constable Koothuru 1 55 1963 Manchi Chedu 1 56 1963 Pempudu Koothuru 1 57 1963 Punarjanma 1 58 1964 Devatha 1 59 1964 Mauali Krishna 1 60 1964 Pooja Phalam 1 61 1965 Aatma Gowravam 1 62 1965 Bangaru Panjaram 1 63 1965 Gudi Gantalu 1 64 1965 Manushulu Mamathalu 1 65 1965 Tene Manasulu 1 66 1965 Uyyala -

Title ID Titlename Category Name Starring Starring D0872 15

Title ID TitleName Category Name Starring Starring D0872 15 MINUTES Action ROBERT DE NIRO EDWARD BURNS D2238 13 MOONS Adventure STEVE BUSCEMI PETER DINKLAGE D2323 13 GOING ON 30 Comedy JENNIFER GARNER MARK RUFFALO D2365 10.5 Action KIM DELANEY BEAU BRIDGES D7019 102 DALMATIANS Childrens GLENN CLOSE GERARD DEPARDIEU D7359 15 PARK AVENUE Family SHABANA AZMI KONKONA SENSHARMA D7589 16 BLOCKS Action BRUCE WILLIS MOS DEF D7615 18 FINGERS OF DEATH Comedy JAMES LEW PAT MORITA D7708 100 DAYS Drama DAVID MULWA DAVIS KWIZERA D7737 10.5 APOCALYPSE Action KIM DELANEY DEAN CAIN D7862 10TH & WOLF Action VAL KILMER DENNIS HOPPER D8276 1971 Family MANOJ BAJPAI RAVI KISHAN D8351 10 ITEMS OR LESS Comedy MORGAN FREEMAN PAZ VEGA D8370 15 MINUTES Action ROBERT DE NIRO EDWARD BURNS D8374 13 GOING ON 30 Comedy JENNIFER GARNER MARK RUFFALO D8473 THE 13TH WARRIOR Thriller / Suspense ANTONIO BANDERAS OMAR SHARIF D8771 1408 STEPHEN KING'S Horror SAMUEL L JACKSON JOHN CUSACK D8969 101 DALMATIANS II PATCHS LONDONAnimated ADV D9139 12 MONKEYS Action BRUCE WILLIS BRAD PITT D9266 1947 EARTH Drama AAMIR KHAN NANDITA DAS D9419 THE 11TH HOUR Documentary NARRATED - LEONARDO DICAPRIO D9642 10,000 B.C. Action STEVEN STRAIT CAMILLA BELLE D10008 1000 PLACES TO SEE BEFORE YOUDocumentary DIE COLLECTION 2 D10014 1920 Horror RAJNEESH DUGGAI ADAH SHARMA D10213 10 ITEMS OR LESS SEASON 1 N 2 Series / Season D10518 187 Action SAMUEL L JACKSON JOHN HEARD D10615 13 B Horror NEETU CHANDRA POONAM DHILLON D10835 12 ROUNDS Action JOHN CENA ASHLEY SCOTT D10920 12 (FOREIGN) Drama SERGEY MAKOVETSKY -

Download the Dus Kahaniyaan Movie 720P

Download The Dus Kahaniyaan Movie 720p 1 / 4 2 / 4 Download The Dus Kahaniyaan Movie 720p 3 / 4 Dus Kahaniyaan Hindi Movie Online - Sanjay Dutt, Sunil Shetty and Arbaaz Khan. ... Bhi Karega 2001 Hindi 720p HDRip 950mb Full Movie Download F Movies.. Nache Nagin Gali Gali (1989): MP3 Songs download, Downloadming, Direct ..... Movie Download Full HD AVI, BluRay, 720p, Mp4 HD, 300MB,480P, 1080p,. ... The illustrated dust jacket shows some age related discoloration overall and wear on ... Nagin Episode 3 Watch Video Dailymotion On Geo Kahani- 19th April 2017 .... Spider-Man 3 Full HD Movie Download In Hindi Dual Audio 720p (Visited 435 times, . Dus Kahaniyaan . TV Shows HD Wallpapers Hindi .... Download The Dus Kahaniyaan Movie 720p. Issue #302 new · Eric Turner repo owner created an issue 2018-07-07 .... Dus Kahaniyaan 2007 Hindi Movie Download. IMDB Ratings: 5.8/10. Genres: Crime, Drama Language: Hindi Quality: 720p DVDRip. Dus Kahaniyaan ( transl. Ten stories) is a 2007 Indian Hindi-language anthology film .... The movie ended up with mostly negative reviews with some average reviews. Elvis Dsilva of rediff gave the movie 2.5 stars saying "it failed to create an extent .... Fortunes are made and squandered, honor betrayed and redeemed, and love lost and rediscovered.. Dus Kahaniyaan 2007 - Full Movie | FREE DOWNLOAD | TORRENT | HD 1080p | x264 | WEB-DL | DD5.1 | H264 | MP4 | 720p | DVD | Bluray.. Dus Kahaniyaan Poster. An anthology of ten ... Trending Hindi Movies and Shows ... More Like This. Dus · Kaante · Musafir · Zinda · Main, Meri Patni... Aur Woh!. Dus Kahaniyaan 2007 Hindi 720p DVDRip 800mb. March 18, 2018 Bollywood Movies 720p Crime Movies .. -

57Th National Film Awards

5 57 7 T TH H T The poster of the winning feature film at the 57th National Awards 2010, Kutty Srank. at the 57th National Awards film The poster of the winning feature NATIONAL FILM AWARDS 2009 FILM AWARDS NATIONAL NATIONAL FILM AWARDS 2009 FILM AWARDS NATIONAL N DirectorateDirectorate ofof FilmFilm Festivals,Festivals, MinistryMinistry ofof InformationInformation & Broadcasting,Broadcasting, GGovernmentovernment ooff h e A IIndiandia presentspresents tthehe oofficialfficial cataloguecatalogue ofof yyhehe 557th7th NationalNational FFilmilm AAwards.wards. p T o I s O t e N r A o f L t h F e I w L i M n n i n A g W f e A a R t u D r th2009 e S f i l 2 m 0 a 0 t t 9 h e 5 57 7 t h N a t i o n NATIONAL FILM a l A w a r d s 2 0 1 0 , AWARDS K u t t THE OFFICIAL CATALOGUE y S r a n k . THE OFFICIAL CATALOGUE T THE OFFICIAL CATALOGUE H E O F F I C I A L C A T A L O G U th E OFFICIAL PRODUCERS 57 20 OF THIS CATALOGUE NATIONAL FILM 0 Visit us at Siri Fort Auditorium Complex, August Kranti Marg, New Delhi-110049 Delhi-110049 Kranti Marg, New August Complex, Auditorium Siri Fort us at Visit AWARDS 9 57th2009 NATIONAL FILM AWARDS THE OFFICIAL CATALOGUE The National Film Awards were constituted in 1953 to recognise and acknowledge the best of Indian cinema in each given year, in all Indian languages.