The Stairs Fleet of Halifax: 1788-1926 James D. Frost

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Saami and Scandinavians in the Viking

Jurij K. Kusmenko Sámi and Scandinavians in the Viking Age Introduction Though we do not know exactly when Scandinavians and Sámi contact started, it is clear that in the time of the formation of the Scandinavian heathen culture and of the Scandinavian languages the Scandinavians and the Sámi were neighbors. Archeologists and historians continue to argue about the place of the original southern boarder of the Sámi on the Scandinavian peninsula and about the place of the most narrow cultural contact, but nobody doubts that the cultural contact between the Sámi and the Scandinavians before and during the Viking Age was very close. Such close contact could not but have left traces in the Sámi culture and in the Sámi languages. This influence concerned not only material culture but even folklore and religion, especially in the area of the Southern Sámi. We find here even names of gods borrowed from the Scandinavian tradition. Swedish and Norwegian missionaries mentioned such Southern Sámi gods such as Radien (cf. norw., sw. rå, rådare) , Veralden Olmai (<Veraldar goð, Frey), Ruona (Rana) (< Rán), Horagalles (< Þórkarl), Ruotta (Rota). In Lule Sámi we find no Scandinavian gods but Scandinavian names of gods such as Storjunkare (big ruler) and Lilljunkare (small ruler). In the Sámi languages we find about three thousand loan words from the Scandinavian languages and many of them were borrowed in the common Scandinavian period (550-1050), that is before and during the Viking Age (Qvigstad 1893; Sammallahti 1998, 128-129). The known Swedish Lapponist Wiklund said in 1898 »[...] Lapska innehåller nämligen en mycket stor mängd låneord från de nordiska språken, av vilka låneord de äldsta ovillkorligen måste vara lånade redan i urnordisk tid, dvs under tiden före ca 700 år efter Kristus. -

18Th Viking Congress Denmark, 6–12 August 2017

18th Viking Congress Denmark, 6–12 August 2017 Abstracts – Papers and Posters 18 TH VIKING CONGRESS, DENMARK 6–12 AUGUST 2017 2 ABSTRACTS – PAPERS AND POSTERS Sponsors KrKrogagerFondenoagerFonden Dronning Margrethe II’s Arkæologiske Fond Farumgaard-Fonden 18TH VIKING CONGRESS, DENMARK 6–12 AUGUST 2017 ABSTRACTS – PAPERS AND POSTERS 3 Welcome to the 18th Viking Congress In 2017, Denmark is host to the 18th Viking Congress. The history of the Viking Congresses goes back to 1946. Since this early beginning, the objective has been to create a common forum for the most current research and theories within Viking-age studies and to enhance communication and collaboration within the field, crossing disciplinary and geographical borders. Thus, it has become a multinational, interdisciplinary meeting for leading scholars of Viking studies in the fields of Archaeology, History, Philology, Place-name studies, Numismatics, Runology and other disciplines, including the natural sciences, relevant to the study of the Viking Age. The 18th Viking Congress opens with a two-day session at the National Museum in Copenhagen and continues, after a cross-country excursion to Roskilde, Trelleborg and Jelling, in the town of Ribe in Jylland. A half-day excursion will take the delegates to Hedeby and the Danevirke. The themes of the 18th Viking Congress are: 1. Catalysts and change in the Viking Age As a historical period, the Viking Age is marked out as a watershed for profound cultural and social changes in northern societies: from the spread of Christianity to urbanisation and political centralisation. Exploring the causes for these changes is a core theme of Viking Studies. -

10 Am Class Syllabus

History 4260.001 Spring 2016 MWF 9 – 9:50 am Maritime History of the Wooten Hall 119 Age of Sail: 1588-1838 Dr. Donald K. Mitchener Office: Wooten Hall Room 228 e-mail: [email protected] Required Books: Hattendorf, John, ed. Maritime History: The Eighteenth Century and the Classic Age of Sail Mack, John. The Sea: A Cultural History Padfield, Peter. Maritime Supremacy and the Opening of the Western Mind: Naval Campaigns that Shaped the Modern World Padfield, Peter. Maritime Power and Struggle For Freedom: Naval Campaigns that Shaped the Modern World 1788-1851 Purpose of this Course: The open oceans of this planet were the great common areas around which Europeans and their social/cultural progeny created what they proclaimed to be the “modern world.” At the heart of this creation lay the European- dominated economic system that depended upon access to and reasonably unfettered use of the sea. This course looks at the development of that system during the period known as the “Age of Sail.” Course topics include the maritime aspects of European exploration of the world, the development of ships and navigational technology, naval developments, general maritime economic theory, and maritime cultural history. Course Requirements and Grading Policies: Students will take three (3) major exams. In addition, they will write two (2) book reviews. All will be graded on a strict 100-point scale. The final will NOT be comprehensive. Graduate Students: Graduate students taking this class will write a 20-page historiographical paper in lieu of the two undergraduate book reviews. The grades will be assigned as Exams, and Papers (percentage of grade) follows: A = 90 - 100 points 1st Exam (25%) Friday, February 26 B = 80 - 89 points 2nd Exam (25%) Wednesday, March 30 C = 70 - 79 points Book Reviews Due (25%) Monday, April 11 D = 60 - 69 points 3rd Exam - Final (25%) Wednesday, May 11 F = 59 and below (8:00 – 10:00 am) Lectures and Readings: 1. -

Age of Sail Overnight Program Teacher's Manual

Age of Sail Overnight Program Teacher’s Manual “Bringing Maritime History to Life” Copyright 2010 Age of Sail Program San Francisco Maritime National Park Association All Rights Reserved Dear Teachers, Welcome to Age of Sail and thank you so much for choosing to attend our amazing program! This manual contains everything you will need to prepare your class for the Age of Sail overnight program as well as some supplemental in- formation, should you elect to use it. I have updated and streamlined the manual this year and I hope that it is more intuitive and accessible than ever before. We have found that the most successful outcomes occur when teachers connect their fieldtrip to the State Content Standards and Frameworks. Math, Science, Mu- sic, Literature, Language, Theatre, Visual Arts as well as History and Social Sci- ence are all important themes in the Age of Sail program and the manual contains a number of optional activities and projects within these disciplines, should you elect to use them. There are also excellent teacher resources online at www.nps.gov/safr If you or any of the parents are interested in more training we offer one day Par- ent/Teacher Workshops on the first Saturday of every month, from September to May. These provide an excellent opportunity to visit our site, meet some of the staff and actually participate in program tasks usually reserved for the lads. This is also a great chance for us to answer any questions you may have. To sign up for a workshop contact our Education Coordinator at (415) 292-6664 or [email protected]. -

1 a History of Seafaring in the Age of Sail HITO 178 University of California, San Diego Winter, 2015 Professor Mark Hanna Tues

A History of Seafaring in the Age of Sail HITO 178 University of California, San Diego Winter, 2015 Professor Mark Hanna Tuesdays, 12:00-2:50 (or all afternoon) Office: H&SS #4059 Room: H&SS #4025, “Galbraith Room” [email protected] Office Hours: Wednesday 1:15-3:00 A whale ship was my Yale College and my Harvard -Herman Melville, Moby Dick The sea is a hostile environment unfit for human habitation yet for centuries people have risked their lives to travel the oceans. What makes people take to the sea and how did they manage the dangers and difficulties of shipboard life? Life at sea is at times radically different than life on land or it can magnify the struggles we all face (food, water, social peace and cohesion). The sea is a contested space where the laws that govern nation states do not always apply. Many people took to the sea not of their own choosing but through some form of kidnapping and bondage. This course forces students to imagine existence on a whole other plane of being afar from what they are accustomed. How does one survive at sea? What kind of social world is born out of close confinement in trying conditions? Taught in conjunction with the San Diego Maritime Museum and the UCSD Special Collections Library, this course investigates life at sea from the age of discovery to the advent of the steamship. We will investigate discovery, technology, piracy, fisheries, commerce, naval conflict, and seaboard life and seaport activity. Readings -W. Jeffrey Bolster, The Mortal Sea: Fishing the Atlantic in the Age of Sail (2012) -Richard Henry Dana, Two Years Before the Mast (1840) (Purchase or read online) Everything else is in Special Collections or online. -

Full Issue Vol. 2 No. 4

Swedish American Genealogist Volume 2 | Number 4 Article 1 12-1-1982 Full Issue Vol. 2 No. 4 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.augustana.edu/swensonsag Part of the Genealogy Commons, and the Scandinavian Studies Commons Recommended Citation (1982) "Full Issue Vol. 2 No. 4," Swedish American Genealogist: Vol. 2 : No. 4 , Article 1. Available at: https://digitalcommons.augustana.edu/swensonsag/vol2/iss4/1 This Full Issue is brought to you for free and open access by Augustana Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Swedish American Genealogist by an authorized editor of Augustana Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Swedish American Genea o ist A journal devoted to Swedish American biography, genealogy and personal history CONTENTS The Emigrant Register of Karlstad 145 Swedish American Directories 150 Norwegian Sailor Last Survivor 160 Norwegian and Swedish Local Histories 161 An Early Rockford Swede 171 Swedish American By-names 173 Literature 177 Ancestor Tables 180 Genealogical Queries 183 Index of Personal Names 187 Index of Place Names 205 Index of Ships' Names 212 Vol. II December 1982 No. 4 I . Swedish Americanij Genealogist ~ Copyright © I 982 S1tiedish Amerh·an Geneal,,gtst P. 0 . Box 2186 Winte r Park. FL 32790 !I SSN 0275-9314 ) Editor and P ub lisher Nils Will ia m Olsson. Ph.D .. F.A.S.G. Contributing Editors Glen E. Brolardcr. Augustana Coll ege . Rock Island. IL: Sten Carls,on. Ph.D .. Uppsala Uni versit y. Uppsala . Sweden: Carl-Erik Johans,on. Brigham Young Univ ersity.J>rovo. UT: He nn e Sol Ib e . -

A History of German-Scandinavian Relations

A History of German – Scandinavian Relations A History of German-Scandinavian Relations By Raimund Wolfert A History of German – Scandinavian Relations Raimund Wolfert 2 A History of German – Scandinavian Relations Table of contents 1. The Rise and Fall of the Hanseatic League.............................................................5 2. The Thirty Years’ War............................................................................................11 3. Prussia en route to becoming a Great Power........................................................15 4. After the Napoleonic Wars.....................................................................................18 5. The German Empire..............................................................................................23 6. The Interwar Period...............................................................................................29 7. The Aftermath of War............................................................................................33 First version 12/2006 2 A History of German – Scandinavian Relations This essay contemplates the history of German-Scandinavian relations from the Hanseatic period through to the present day, focussing upon the Berlin- Brandenburg region and the northeastern part of Germany that lies to the south of the Baltic Sea. A geographic area whose topography has been shaped by the great Scandinavian glacier of the Vistula ice age from 20000 BC to 13 000 BC will thus be reflected upon. According to the linguistic usage of the term -

Team Effort at IPP • Working on the Largest Building in NB • • Alt Hotel • Shipping Steel to Texas (Then Peru) • Recognition Dinner • Pg.6 Pg.19 Pg.31

fall & winter 2013 The biannual newsmagazine of t he OSCO Construction Group OSCO construction group • Team Effort at IPP • Working on the Largest Building in NB • • Alt Hotel • Shipping Steel to Texas (then Peru) • Recognition Dinner • pg.6 pg.19 pg.31 What’s Inside... fall & winter 2013 3 Message from the President 30 Harbour Bridge Refurbishment, Saint John, NB priorities profiles 31 Group Safety News 21 Customer Profile: Erland Construction 32 OSCO Environmental Management System 24 Product Profile: Precast Infrastructure 33` Information Corner 33 Sackville Facility Renovations public & community 34 Touch a Truck projects 34 NSCC Foundation Bursary Award 4 Irving Pulp & Paper, Saint John, NB 35 Steel Day 6 Kent Distribution Centre, Moncton, NB 35 National Precast Day 8 Alt Hotel, Halifax, NS 36 Pte. David Greenslade Peace Park 9 Non-Reactive Stone at OSCO Aggregates 10 South Beach Psychiatric Center, Staten Island, NY people 11 Irving Big Stop, Enfield, NS 37 Event Planning Committees 12 Lake Utopia Paper, Lake Utopia, NB 37 OSCO Group Bursary Winners 14 Irving Oil Refinery, Saint John, NB 38 Employee Recognition Dinner 16 Jasper Wyman & Son Blueberries, Charlottetown, PE 40 OSCO Golf Challenge 17 Shipping Steel to Texas (& Peru) 40 Retirement Lane Gary Bogle, Gary Fillmore, Roland Froude, Raymond Goguen, Joyce 18 Rebar, misc. projects Murray, Raymond Price, Dale Smith, Brian Underwood, Alfred Ward 19 Pier 8 & Fairview Cove Caissons, Halifax, NS 42 National Safety Award for Strescon 20 3rd Avenue, Burlington, MA 42 Group Picnic 22 Miscellaneous Metals Division, update 43 Fresh Faces 22 Ravine Centre II, Halifax, NS 43 Wall of Fame 23 Hermanville Wind Farm, Hermanville, PE 43 Congratulations 29 Cape Breton University, Cape Breton, NS 44 Our Locations OSCO 29 Regent Street Redevelopment, Fredericton, NB construction 30 DND Explosive Storage Facility, Halifax, NS group CONNECTIONS is the biannual magazine of the OSCO on our cover.. -

Ships and Sailors in Early Twentieth-Century Maritime Fiction

In the Wake of Conrad: Ships and Sailors in Early Twentieth-Century Maritime Fiction Alexandra Caroline Phillips BA (Hons) Cardiff University, MA King’s College, London A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Cardiff University 30 March 2015 1 Table of Contents Abstract 3 Acknowledgements 4 Introduction - Contexts and Tradition 5 The Transition from Sail to Steam 6 The Maritime Fiction Tradition 12 The Changing Nature of the Sea Story in the Twentieth Century 19 PART ONE Chapter 1 - Re-Reading Conrad and Maritime Fiction: A Critical Review 23 The Early Critical Reception of Conrad’s Maritime Texts 24 Achievement and Decline: Re-evaluations of Conrad 28 Seaman and Author: Psychological and Biographical Approaches 30 Maritime Author / Political Novelist 37 New Readings of Conrad and the Maritime Fiction Tradition 41 Chapter 2 - Sail Versus Steam in the Novels of Joseph Conrad Introduction: Assessing Conrad in the Era of Steam 51 Seamanship and the Sailing Ship: The Nigger of the ‘Narcissus’ 54 Lord Jim, Steam Power, and the Lost Art of Seamanship 63 Chance: The Captain’s Wife and the Crisis in Sail 73 Looking back from Steam to Sail in The Shadow-Line 82 Romance: The Joseph Conrad / Ford Madox Ford Collaboration 90 2 PART TWO Chapter 3 - A Return to the Past: Maritime Adventures and Pirate Tales Introduction: The Making of Myths 101 The Seduction of Silver: Defoe, Stevenson and the Tradition of Pirate Adventures 102 Sir Arthur Conan Doyle and the Tales of Captain Sharkey 111 Pirates and Petticoats in F. Tennyson Jesse’s -

Legacy of the Pacific War: 75 Years Later August 2020

LEGACY OF THE PACIFIC WAR: 75 YEARS LATER August 2020 World War II in the Pacific and the Impact on the U.S. Navy By Rear Admiral Samuel J. Cox, U.S. Navy (Retired) uring World War II, the U.S. Navy fought the Pacific. World War II also saw significant social in every ocean of the world, but it was change within the U.S. Navy that carried forward the war in the Pacific against the Empire into the Navy of today. of Japan that would have the greatest impact on As it was at the end of World War II, the premier Dshaping the future of the U.S. Navy. The impact was type of ship in the U.S. Navy today is the aircraft so profound, that in many ways the U.S. Navy of carrier, protected by cruiser and destroyer escorts, today has more in common with the Navy in 1945 with the primary weapon system being the aircraft than the Navy at the end of World War II had with embarked on the carrier. (Command of the sea first the Navy in December 1941. With the exception and foremost requires command of the air over the of strategic ballistic missile submarines, virtually Asia sea, otherwise ships are very vulnerable to aircraft, every type of ship and command organization today Program as they were during World War II.) The carriers and is descended from those that were invented or escorts of today are bigger, more technologically matured in the crucible of World War II combat in sophisticated, and more capable than those of World Asia Program War II, although there are fewer of them. -

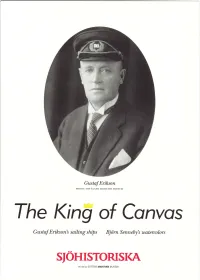

The Ki Ng of Conyos

The Ki ng of Conyos Gustaf Erikson's sai,ling shi,ps Bjtirn Senneby's watercolors sIoHrsToRrsKA en del av STATENS MARITIMA MUSEER ri#{ffi' r+f,**&:;]!$@$j! jr:+{ff 1*.; ff. Pamir Watercolor fu Bji;rn Senneby. GUSTAF ERIKSON The ship's owner, Gustaf Erikson, was born on Europe. The shipping company w:ls at its largest z4 October, r87z in Lemland, in southern Åland. in rg35, when Gustav was 58 years old. At the Both his father and grandfather had worked at time, the company had z9 vessels r5 of which sea. Gustafsson started his life at sea as a tG'year- were large sailing ships without alternative means old, when he served as a cabin boy on the bark of propulsion. GustafAdolf Mauritz Erikson died Neptun over the summer. When he reached r3, on August Lbn, rg47 in Mariehamn. he worked as a cook on the same vessel. He Gustaf Erikson was also part owner of advanced through the ranks and in r89r, at rg several steamers and motor vessels, but it was as years old, was the master's assistant on the barque the owner of the great sailing ships that he was Southern Bellc.In rgoo he took his captain's exlm best known. Four of his large sailing vessels, all and betr,veen 19o6 and r9r3 he was an executive four-masted steel barques, are preserved to this officer on different oceangoing voyages. day: Moshulu,whichwon the lastgrain race tggg, Over the years he had bought shares in is now a restaurant in Philadelphia, USA. -

The Hostages of the Northmen: from the Viking Age to the Middle Ages

Part IV: Legal Rights It has previously been mentioned how hostages as rituals during peace processes – which in the sources may be described with an ambivalence, or ambiguity – and how people could be used as social capital in different conflicts. It is therefore important to understand how the persons who became hostages were vauled and how their new collective – the new household – responded to its new members and what was crucial for his or her status and participation in the new setting. All this may be related to the legal rights and special privileges, such as the right to wear coat of arms, weapons, or other status symbols. Personal rights could be regu- lated by agreements: oral, written, or even implied. Rights could also be related to the nature of the agreement itself, what kind of peace process the hostage occurred in and the type of hostage. But being a hostage also meant that a person was subjected to restric- tions on freedom and mobility. What did such situations meant for the hostage-taking party? What were their privileges and obli- gations? To answer these questions, a point of departure will be Kosto’s definition of hostages in continental and Mediterranean cultures around during the period 400–1400, when hostages were a form of security for the behaviour of other people. Hostages and law The hostage had its special role in legal contexts that could be related to the discussion in the introduction of the relationship between religion and law. The views on this subject are divided How to cite this book chapter: Olsson, S.