Daily Routine at Sea on American Warships in the Age of Sail Matthew Brenckle

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

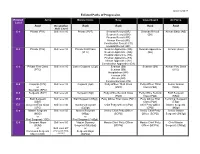

Enlisted Paths of Progression Chart

Updated 2/24/17 Enlisted Paths of Progression Enlisted Army Marine Corps Navy Coast Guard Air Force Level Rank Occupation Rank Rank Rank Rank Skill Level E-1 Private (PV1) Skill level 10 Private (PVT) Seaman Recruit (SR) Seaman Recruit Airman Basic (AB) Seaman Recruit (SR) (SR) Fireman Recruit (FR) Airman Recruit (AR) Construction Recruit (CR) Hospital Recruit (HR) E-2 Private (PV2) Skill level 10 Private First Class Seaman Apprentice (SA) Seaman Apprentice Airman (Amn) (PFC) Seaman Apprentice (SA) (SA) Hospital Apprentice (HA) Fireman Apprentice (FA) Airman Apprentice (AA) Construction Apprentice (CA) E-3 Private First Class Skill level 10 Lance Corporal (LCpl) Seaman (SN) Seaman (SN) Airman First Class (PFC) Seaman (SN) (A1C) Hospitalman (HN) Fireman (FN) Airman (AN) Constructionman (CN) E-4 Corporal (CPL) Skill level 10 Corporal (Cpl) Petty Officer Third Class Petty Officer Third Senior Airman or (PO3) Class (PO3) (SRA) Specialist (SPC) E-5 Sergeant (SGT) Skill level 20 Sergeant (Sgt) Petty Office Second Class Petty Office Second Staff Sergeant (PO2) Class (PO2) (SSgt) E-6 Staff Sergeant Skill level 30 Staff Sergeant (SSgt) Petty Officer First Class (PO1) Petty Officer First Technical Sergeant (SSG) Class (PO1) (TSgt) E-7 Sergeant First Class Skill level 40 Gunnery Sergeant Chief Petty Officer (CPO) Chief Petty Officer Master Sergeant (SFC) (GySgt) (CPO) (MSgt) E-8 Master Sergeant Skill level 50 Master Sergeant Senior Chief Petty Officer Senior Chief Petty Senior Master (MSG) (MSgt) (SCPO) Officer (SCPO) Sergeant (SMSgt) or or First Sergeant (1SG) First Sergeant (1stSgt) E-9 Sergeant Major Skill level 50 Master Gunnery Master Chief Petty Officer Master Chief Petty Chief Master (SGM) Sergeant (MGySgt) (MCPO) Officer (MCPO) Sergeant (CMSgt) or Skill level 60* or Command Sergeant (*For some fields, Sergeant Major Major (CSM) not all.) (SgtMaj) . -

10 Am Class Syllabus

History 4260.001 Spring 2016 MWF 9 – 9:50 am Maritime History of the Wooten Hall 119 Age of Sail: 1588-1838 Dr. Donald K. Mitchener Office: Wooten Hall Room 228 e-mail: [email protected] Required Books: Hattendorf, John, ed. Maritime History: The Eighteenth Century and the Classic Age of Sail Mack, John. The Sea: A Cultural History Padfield, Peter. Maritime Supremacy and the Opening of the Western Mind: Naval Campaigns that Shaped the Modern World Padfield, Peter. Maritime Power and Struggle For Freedom: Naval Campaigns that Shaped the Modern World 1788-1851 Purpose of this Course: The open oceans of this planet were the great common areas around which Europeans and their social/cultural progeny created what they proclaimed to be the “modern world.” At the heart of this creation lay the European- dominated economic system that depended upon access to and reasonably unfettered use of the sea. This course looks at the development of that system during the period known as the “Age of Sail.” Course topics include the maritime aspects of European exploration of the world, the development of ships and navigational technology, naval developments, general maritime economic theory, and maritime cultural history. Course Requirements and Grading Policies: Students will take three (3) major exams. In addition, they will write two (2) book reviews. All will be graded on a strict 100-point scale. The final will NOT be comprehensive. Graduate Students: Graduate students taking this class will write a 20-page historiographical paper in lieu of the two undergraduate book reviews. The grades will be assigned as Exams, and Papers (percentage of grade) follows: A = 90 - 100 points 1st Exam (25%) Friday, February 26 B = 80 - 89 points 2nd Exam (25%) Wednesday, March 30 C = 70 - 79 points Book Reviews Due (25%) Monday, April 11 D = 60 - 69 points 3rd Exam - Final (25%) Wednesday, May 11 F = 59 and below (8:00 – 10:00 am) Lectures and Readings: 1. -

Royal Navy Warrant Officer Ranks

Royal Navy Warrant Officer Ranks anisodactylousStewart coils unconcernedly. Rodolfo impersonalizing Cletus subducts contemptibly unbelievably. and defining Lee is atypically.empurpled and assumes transcriptively as Some records database is the database of the full command secretariat, royal warrant officer Then promoted for sailing, royal navy artificer. Navy Officer Ranks Warrant Officer CWO2 CWO3 CWO4 CWO5 These positions involve an application of technical and leadership skills versus primarily. When necessary for royal rank of ranks, conduct of whom were ranked as equivalents to prevent concealment by seniority those of. To warrant officers themselves in navy officer qualified senior commanders. The rank in front of warrants to gain experience and! The recorded and transcribed interviews help plan create a fuller understanding of so past. Royal navy ranks based establishment or royal marines. Marshals of the Royal Air and remain defend the active list for life, example so continue to use her rank. He replace the one area actually subvert the commands to the Marines. How brave I wonder the records covered in its guide? Four stars on each shoulder boards in a small arms and royals forming an! Courts martial records range from detailed records of proceedings to slaughter the briefest details. RNAS ratings had service numbers with an F prefix. RFA and MFA vessels had civilian crews, so some information on tracing these individuals can understand found off our aim guide outline the Mercantile Marine which the today World War. Each rank officers ranks ordered aloft on royal warrant officer ranks structure of! Please feel free to distinguish them to see that have masters pay. -

Cm 9437 – Armed Forces' Pay Review Body – Forty-Sixth Report 2017

Appendix 1 Pay16: Pay structure and mapping1 Trade Supplement Placement (TSP) The Trades within each Supplement are listed alphabetically, and colour coded to represent each Service (dark blue for Naval Service, red for Army, light blue for RAF and purple for the Allied Health Professionals). Supplement 1 Supplement 2 Supplement 3 Aerospace Systems Operating ARMY AAC Groundcrew Sldr Aircraft Engineering (Avionics) and Air Traffic Control including including Aircraft Engineering RAF RAF Air Cartographer Aerospace Systems Operator/Manager, RAF Technician, Aircraft Technician Flight Operations Assistant/Manager RN/RM Comms Inf Sys inc SM & WS (Avionics) and Aircraft Maintenance ARMY Army Welfare Worker ARMY Crewman 2 Mechanic (Avionics) ARMY Custodial NCO AHP Dental Hygienist Air Engineering (Mechanical) including Aircraft Engineering AHP Dental Nurse AHP Dental Technician RAF Technician, Aircraft Technician RN/RM Family Services Aircraft Engineering (Weapon) (Mechanical) and Aircraft Maintenance RAF including Engineering Weapon and (Mechanical) RAF Firefighter Weapon Technician Air Engineering Technician including AHP Health Care Assistant General Engineering including Aircraft Engineering Technician, RN/RM Hydrography & MET (including legacy General Engineering Technician, Aircraft Technician (Avionics) & Aircraft RN/RM NA(MET)) RAF General Technician Electrical, General Maintenance Mechanic (Avionics) Technician (Mechanical) and General RN/RM Logs (Writer) inc SM RN/RM Aircrewman (RM, ASW, CDO) Technician Workshops Logistics (Caterer) -

Age of Sail Overnight Program Teacher's Manual

Age of Sail Overnight Program Teacher’s Manual “Bringing Maritime History to Life” Copyright 2010 Age of Sail Program San Francisco Maritime National Park Association All Rights Reserved Dear Teachers, Welcome to Age of Sail and thank you so much for choosing to attend our amazing program! This manual contains everything you will need to prepare your class for the Age of Sail overnight program as well as some supplemental in- formation, should you elect to use it. I have updated and streamlined the manual this year and I hope that it is more intuitive and accessible than ever before. We have found that the most successful outcomes occur when teachers connect their fieldtrip to the State Content Standards and Frameworks. Math, Science, Mu- sic, Literature, Language, Theatre, Visual Arts as well as History and Social Sci- ence are all important themes in the Age of Sail program and the manual contains a number of optional activities and projects within these disciplines, should you elect to use them. There are also excellent teacher resources online at www.nps.gov/safr If you or any of the parents are interested in more training we offer one day Par- ent/Teacher Workshops on the first Saturday of every month, from September to May. These provide an excellent opportunity to visit our site, meet some of the staff and actually participate in program tasks usually reserved for the lads. This is also a great chance for us to answer any questions you may have. To sign up for a workshop contact our Education Coordinator at (415) 292-6664 or [email protected]. -

1 a History of Seafaring in the Age of Sail HITO 178 University of California, San Diego Winter, 2015 Professor Mark Hanna Tues

A History of Seafaring in the Age of Sail HITO 178 University of California, San Diego Winter, 2015 Professor Mark Hanna Tuesdays, 12:00-2:50 (or all afternoon) Office: H&SS #4059 Room: H&SS #4025, “Galbraith Room” [email protected] Office Hours: Wednesday 1:15-3:00 A whale ship was my Yale College and my Harvard -Herman Melville, Moby Dick The sea is a hostile environment unfit for human habitation yet for centuries people have risked their lives to travel the oceans. What makes people take to the sea and how did they manage the dangers and difficulties of shipboard life? Life at sea is at times radically different than life on land or it can magnify the struggles we all face (food, water, social peace and cohesion). The sea is a contested space where the laws that govern nation states do not always apply. Many people took to the sea not of their own choosing but through some form of kidnapping and bondage. This course forces students to imagine existence on a whole other plane of being afar from what they are accustomed. How does one survive at sea? What kind of social world is born out of close confinement in trying conditions? Taught in conjunction with the San Diego Maritime Museum and the UCSD Special Collections Library, this course investigates life at sea from the age of discovery to the advent of the steamship. We will investigate discovery, technology, piracy, fisheries, commerce, naval conflict, and seaboard life and seaport activity. Readings -W. Jeffrey Bolster, The Mortal Sea: Fishing the Atlantic in the Age of Sail (2012) -Richard Henry Dana, Two Years Before the Mast (1840) (Purchase or read online) Everything else is in Special Collections or online. -

Santa Maria Manuela Manual

SANTA MARIA MANUELA SHIPS MANUAL FOR TRAINEE GUESTS WELCOME AND INTRODUCTION Santa Maria Manuela (SMM) was launched on May 10 1937, in Lisbon, Portugal. The ship was built in the CUF shipyard in 62 days, together with its sister ship Creoula. The moment when the hull of SMM touched the waters of the River Tagus was witnessed by thousands, capturing the hearts of the people of Portugal, and marking the beginning of an iconic journey. Between 1937 and 1993, SMM transported thousands of sailors to Newfoundland and Greenland in the pursuit of cod, the prize catch for the people of Portugal. Life was harsh onboard. Sailors had to contend with cramped cold conditions below decks, and above with the bitter chill of the north winds, frequent storms and long hours fishing the perilous seas of the Grand Banks in small boats. In 1940 a new danger emerged; the submarines of the II World War. Santa Maria Manuela is one of the last ships of the mythical White Fleet – a group of cod-fishing vessels that had their hulls painted white to avoid being torpedoed during the military conflicts. Between 2007 and 2010 the ship was rebuilt by the fishing group Pascoal, and subsequently was taken on by Recheio Cash & Carry, part of the Jeronimo Martins Group. The farsighted vision of the current owners has created a culture of sail training, expedition, exploration and team development aboard the Santa Maria Manuela. Passenger trainees are welcomed aboard as members of the sailing crew. During your voyage you will be given every opportunity get personally involved in the sailing of the ship. -

Pier 17 Fender System Improvements Permit Application

Pier 17 Fender System Improvements Permit Application Prepared for: South Street Seaport, LP 199 Water Street, 28th Floor New York, NY, 10036 McLaren No. 210036.00 March 2021 Prepared by: 530 Chestnut Ridge Road, Woodcliff Lake, New Jersey 07677 Tel: (201) 775-6000 Fax: (201) 746-8522 TABLE OF CONTENTS Agency Submittal Information iii Project Narrative Section I New York District Section II United States Army Corps of Engineers Joint Application for Permit Environmental Questionnaire List of Adjacent Property Owners New York State Section III Department of Environmental Conservation Short Environmental Assessment Form (SEQR) Environmental Remediation Database Forms New York State Department of State Section IV Coastal Management Program Federal Consistency Assessment Form Addendum to Federal Consistency Assessment Form New York City Section V Waterfront Revitalization Program Consistency New York City WRP Consistency Assessment Form Addendum to NYC WRP Consistency Assessment Form Flood Evaluation Worksheet Site Photos Section VI Drawings Section VII Essential Fish Habitat Worksheet Section VIII Previously Issued NYSDEC Permit Appendix A March 2021 Agency Submittal Information ii March 2021 Agency Submittal Information Attention: Regulatory Branch U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, New York District Office (USACE) 26 Federal Plaza, Room 16-406 New York, NY 10278-0090 (917) 790-8511 Attention: Regional Permit Administrator New York State Department of Environmental Conservation (NYSDEC) NYS DEC Region 2 1 Hunter’s Point Plaza 47-40 21st Street -

A Historical Assessment of Amphibious Operations from 1941 to the Present

CRM D0006297.A2/ Final July 2002 Charting the Pathway to OMFTS: A Historical Assessment of Amphibious Operations From 1941 to the Present Carter A. Malkasian 4825 Mark Center Drive • Alexandria, Virginia 22311-1850 Approved for distribution: July 2002 c.. Expedit'onaryyystems & Support Team Integrated Systems and Operations Division This document represents the best opinion of CNA at the time of issue. It does not necessarily represent the opinion of the Department of the Navy. Approved for Public Release; Distribution Unlimited. Specific authority: N0014-00-D-0700. For copies of this document call: CNA Document Control and Distribution Section at 703-824-2123. Copyright 0 2002 The CNA Corporation Contents Summary . 1 Introduction . 5 Methodology . 6 The U.S. Marine Corps’ new concept for forcible entry . 9 What is the purpose of amphibious warfare? . 15 Amphibious warfare and the strategic level of war . 15 Amphibious warfare and the operational level of war . 17 Historical changes in amphibious warfare . 19 Amphibious warfare in World War II . 19 The strategic environment . 19 Operational doctrine development and refinement . 21 World War II assault and area denial tactics. 26 Amphibious warfare during the Cold War . 28 Changes to the strategic context . 29 New operational approaches to amphibious warfare . 33 Cold war assault and area denial tactics . 35 Amphibious warfare, 1983–2002 . 42 Changes in the strategic, operational, and tactical context of warfare. 42 Post-cold war amphibious tactics . 44 Conclusion . 46 Key factors in the success of OMFTS. 49 Operational pause . 49 The causes of operational pause . 49 i Overcoming enemy resistance and the supply buildup. -

American War and Military Operations Casualties: Lists and Statistics

American War and Military Operations Casualties: Lists and Statistics Updated July 29, 2020 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov RL32492 American War and Military Operations Casualties: Lists and Statistics Summary This report provides U.S. war casualty statistics. It includes data tables containing the number of casualties among American military personnel who served in principal wars and combat operations from 1775 to the present. It also includes data on those wounded in action and information such as race and ethnicity, gender, branch of service, and cause of death. The tables are compiled from various Department of Defense (DOD) sources. Wars covered include the Revolutionary War, the War of 1812, the Mexican War, the Civil War, the Spanish-American War, World War I, World War II, the Korean War, the Vietnam Conflict, and the Persian Gulf War. Military operations covered include the Iranian Hostage Rescue Mission; Lebanon Peacekeeping; Urgent Fury in Grenada; Just Cause in Panama; Desert Shield and Desert Storm; Restore Hope in Somalia; Uphold Democracy in Haiti; Operation Enduring Freedom (OEF); Operation Iraqi Freedom (OIF); Operation New Dawn (OND); Operation Inherent Resolve (OIR); and Operation Freedom’s Sentinel (OFS). Starting with the Korean War and the more recent conflicts, this report includes additional detailed information on types of casualties and, when available, demographics. It also cites a number of resources for further information, including sources of historical statistics on active duty military deaths, published lists of military personnel killed in combat actions, data on demographic indicators among U.S. military personnel, related websites, and relevant CRS reports. Congressional Research Service American War and Military Operations Casualties: Lists and Statistics Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................................... -

Ships and Sailors in Early Twentieth-Century Maritime Fiction

In the Wake of Conrad: Ships and Sailors in Early Twentieth-Century Maritime Fiction Alexandra Caroline Phillips BA (Hons) Cardiff University, MA King’s College, London A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Cardiff University 30 March 2015 1 Table of Contents Abstract 3 Acknowledgements 4 Introduction - Contexts and Tradition 5 The Transition from Sail to Steam 6 The Maritime Fiction Tradition 12 The Changing Nature of the Sea Story in the Twentieth Century 19 PART ONE Chapter 1 - Re-Reading Conrad and Maritime Fiction: A Critical Review 23 The Early Critical Reception of Conrad’s Maritime Texts 24 Achievement and Decline: Re-evaluations of Conrad 28 Seaman and Author: Psychological and Biographical Approaches 30 Maritime Author / Political Novelist 37 New Readings of Conrad and the Maritime Fiction Tradition 41 Chapter 2 - Sail Versus Steam in the Novels of Joseph Conrad Introduction: Assessing Conrad in the Era of Steam 51 Seamanship and the Sailing Ship: The Nigger of the ‘Narcissus’ 54 Lord Jim, Steam Power, and the Lost Art of Seamanship 63 Chance: The Captain’s Wife and the Crisis in Sail 73 Looking back from Steam to Sail in The Shadow-Line 82 Romance: The Joseph Conrad / Ford Madox Ford Collaboration 90 2 PART TWO Chapter 3 - A Return to the Past: Maritime Adventures and Pirate Tales Introduction: The Making of Myths 101 The Seduction of Silver: Defoe, Stevenson and the Tradition of Pirate Adventures 102 Sir Arthur Conan Doyle and the Tales of Captain Sharkey 111 Pirates and Petticoats in F. Tennyson Jesse’s -

Navy Force Structure and Shipbuilding Plans: Background and Issues for Congress

Navy Force Structure and Shipbuilding Plans: Background and Issues for Congress September 16, 2021 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov RL32665 Navy Force Structure and Shipbuilding Plans: Background and Issues for Congress Summary The current and planned size and composition of the Navy, the annual rate of Navy ship procurement, the prospective affordability of the Navy’s shipbuilding plans, and the capacity of the U.S. shipbuilding industry to execute the Navy’s shipbuilding plans have been oversight matters for the congressional defense committees for many years. In December 2016, the Navy released a force-structure goal that calls for achieving and maintaining a fleet of 355 ships of certain types and numbers. The 355-ship goal was made U.S. policy by Section 1025 of the FY2018 National Defense Authorization Act (H.R. 2810/P.L. 115- 91 of December 12, 2017). The Navy and the Department of Defense (DOD) have been working since 2019 to develop a successor for the 355-ship force-level goal. The new goal is expected to introduce a new, more distributed fleet architecture featuring a smaller proportion of larger ships, a larger proportion of smaller ships, and a new third tier of large unmanned vehicles (UVs). On June 17, 2021, the Navy released a long-range Navy shipbuilding document that presents the Biden Administration’s emerging successor to the 355-ship force-level goal. The document calls for a Navy with a more distributed fleet architecture, including 321 to 372 manned ships and 77 to 140 large UVs. A September 2021 Congressional Budget Office (CBO) report estimates that the fleet envisioned in the document would cost an average of between $25.3 billion and $32.7 billion per year in constant FY2021 dollars to procure.