Sustainable Finance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Delivering a Leading Bank for Customers and Investors

Delivering a leading bank for customers and investors Ewen Stevenson, Chief Financial Officer Barclays Global Financial Services Conference, New York 12th September 2016 Investment case Strong customer-centric core(1) bank, well progressed on legacy restructuring . Strong UK / Irish customer franchises capable of collectively generating risk adjusted returns above the cost of equity Core . Building value through a focus on improved customer service and product offering, and above market growth . But we recognise it is a tougher interest rate environment / macro outlook . Continue to run-down; down to 23% of total RWAs at end Legacy portfolios/ Q2 2016 businesses . On track to wind-up Capital Resolution by end 2017 . Making steady progress Legacy conduct . issues Seeking to materially address residual conduct and litigation overhang during H2 2016 / 2017 (1) ‘Core’ comprises the Personal and Business Banking, Commercial and Private Banking and Corporate and Institutional Banking divisions 2 Core – customer franchise strength Q2 2016 core key metrics (£bn) RWAs 190 Royal Bank of Scotland Deposits 310 #1 Business (1) (2) Loans 286 Joint #1 Commercial #2 Personal (3) Ulster NatWest (2) #1 Personal (4) Joint #1 Commercial (1) #1 Business (5) #2 Business #3 Commercial (6) #3 Personal (3) Ulster RoI RBSI Personal RBSI Business #3 Personal (4) (7) (10) #3 Business (5) #1 Isle of Man #1 Isle of Man (8) #3 Commercial (6) Top 2 Guernsey Top 2 Guernsey (11) Top 3 Jersey (9) Top 2 Jersey (12) (1) Royal Bank of Scotland and NatWest Business: Main current -

The Royal Bank of Scotland Group Pie File No

UNITED STATES SECURITI ES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION WASHINGTON, DC 20549 DIVISION OF TRADING AND MARKETS August 3, 20 15 Ms. Connie Milonakis Davis Polk & Wardwell London LLP 5 Aldermanbury Square London EC2V 7HR England Re: The Royal Bank of Scotland Group pie File No. TP 15-17 Dear Ms. Milonakis: In your letter dated August 3, 2015, as supplemented by conversations with the staff, you request on behalf ofThe Royal Bank of Scotland Group plc, a public limited company organized under the laws of the United Kingdom and registered in Scotland ("RBSG"), an exemption from Rule 102 of Regulation Munder the Securities Exchange Act of 1934, as amended ("Exchange Act") in connection with the distribution of the ordinary shares of RBSG ("RBSG Shares") and the American Depositary Shares each representing the right to receive two RBSG Shares ("RBSG ADSs") by way of a placement of RBSG Shares (the "Placing") to interested purchasers by United Kingdom Financial Investments, which manages the shareholding of the United Kingdom Treasury in RBSG. 1 You seek an exemption to permit RBSG and RBSG Affiliates to conduct specified transactions outside the United States in RBSG Ordinary Shares during the Placing. Specifically, you request that: (i) RBSG CIB be permitted to continue to engage in derivatives and investor product market-making and hedging activities as described in your letter; (ii) the RBSG Asset Manager and RBSG Investment Managers be permitted to continue to engage in investment management activities as described in your letter; (iii) the RBSG Trustees and Personal Representatives be permitted to continue to engage in trustee and personal representative-related activities as described in your letter; (iv) the RBSG Banking Units be permitted to continue to engage in banking-related activities as described in your letter; and (v) the RBSG Stock Borrowing and Lending Units be permitted to continue to engage in stock borrowing and lending activities as described in your letter. -

Change of Name Faqs

Change of name FAQs On 14 February 2020, The Royal Bank of Scotland Group plc (the Group) announced its intention to change the Group’s company name from ‘The Royal Bank of Scotland Group plc’ to ‘NatWest Group plc’. It’s anticipated that the name change will become effective later in 2020. 1. Why is the Group changing its name? Given the Group’s progress, the solid financial footing it is now on and the forward- looking customer focused strategy it is implementing, the Board considers this the right time for the Group name to reflect the brand under which the majority of its business is delivered: NatWest. 2. What will happen to the ordinary and/or preference shares I currently hold in the Group? The ordinary and/or preference shares you currently hold in the Group (‘RBS shares’) will continue to exist once the name is legally changed, but the RBS shares will become shares in NatWest Group plc. There will be no change to nominal value or structure of your shareholding as a result of the change of name. 3. What will happen to the share price? This is a legal name change. The share price is influenced by many factors and can go up as well as down. 4. Will I receive a new share certificate? If you hold your RBS shares in certificated form, you won’t receive a new share certificate in the new company name; your existing share certificate(s) will remain valid. Any share certificates issued following the legal change of name will be in the name of NatWest Group plc. -

Natwest Group United Kingdom

NatWest Group United Kingdom Active This profile is actively maintained Send feedback on this profile Created before Nov 2016 Last update: Feb 23 2021 About NatWest Group NatWest Group, founded in 1727, is a British banking and insurance holding company based in Edinburgh, Scotland. Its main subsidiary companies are The Royal Bank of Scotland, NatWest, Ulster Bank and Coutts. Prior to a name-change in July 2020, it was known as Royal Bank of Scotland (RBS) Group. After a massive bailout in 2008, a majority of RBS' shares were purchased by the UK Government. In 2014 the bank embarked on a restructuring process that saw it refocus on its business in the UK and Ireland. As part of this process it divested its ownership of Citizens Financial Group, the 13th largest bank in the United States, in 2015. As of 2020 it remains 61.93% UK Government owned, via UK Financial Investments (UKFI). Website https://www.natwestgroup.com/ Headquarters 36 St Andrew Square EH2 2YB Edinburgh Scotland United Kingdom CEO/chair Alison Rose CEO Supervisor Bank of England Annual report Annual report 2020 Ownership listed on London Stock Exchange Natwest Group is majority-owned by the UK government since 2008, which currently holds 61.93 % of the shares. Complaints NatWest Group does not operate a complaints channel for individuals and communities that may be adversely affected by and its finance. However, the bank can be contacted via the contact form here (e.g. using ‘General Service’ as account type). grievances Stakeholders may raise complaints via the OECD National Contact Points (see OECD Watch guidance). -

RBS Resolution Plan

Logo RBS Public Section RBS Group pic Resolution Plan Pursuant to 12 C.F.R. Parts 217 & 381 and RBS Citizens, N.A. Resolution Plan Pursuant to 12 C.F.R. 360 July 1, 2013 Table of Contents III IntroductionRBS Group pageand RBS 1 Americas page 2 II.CII.BII.A MaterialGlobalPrincipal Operations Supervisory Officers of of RBS AuthoritiesRBS Group Group plcpage page page 4 2 5 IIIII.EII.D RBSCNA SummaryResolution IDI of PlanningPlan Financial and Corporate RBS Information, Citizens Governance, CapitalResolution and Structure PlanMajor page Funding and 10 Processes Sources pagepage 67 III.CIII.BIII.A CoreMaterialSummary Business Entities of Financial Lines page page 11Information, 12 Capital and Major Funding Sources page 13 III.FIII.EIII.D ForeignMembershipDerivative Operations and in HedgingMaterial page Payment,Activities 17 pageClearing 16 and Settlement Systems page 17 III.IIII.HIII.G RBS PrincipalMaterial Citizens' SupervisoryOfficers Resolution page Authorities 17 Planning page Corporate 17 Governance, Structure and III.KIII.JProcesses MaterialHigh-Level page Management Description 18 Information of RBS Citizens' Systems Resolution page 19 Strategy page 20 IV.BIV.AIV Markets CoreMaterial Business & EntitiesInternational Lines page page Banking22 23 Americas page 22 IV.EIV.DIV.C MembershipsDerivativeSummary ofand Financial in Hedging Material Information, Activities Payment, page CapitalClearing 24 and and Major Settlement Funding Systems Sources page page 24 24 IV.HIV.GIV.F ForeignPrincipalMaterial Operations SupervisoryOfficers page page Authorities 25 25 page 25 IV.JIV.I M&IBA'sMaterial ManagementResolution Planning Information Corporate Systems Governance, page 26 Structure and Processes page 25 StrategyIV.K High-Level page 26 Description of Markets & International Banking Americas' Resolution Chapter 1. -

Interfaces & Partners

Interfaces & Partners Data Bloomberg B-Pipe ITG Logic Bloomberg Data License Markit Group Limited Bloomberg Desktop API Proquote Bloomberg Server API Quick Charles River Data Service – Reference Telemet Orion Charles River Data Service – Real-Time The Yield Book Inc. Charles River Data Service – Benchmarks Thomson Reuters DataScope Select AP Pre-Trade Analytics Barclays The Yield Book Inc. ITG Thomson Reuters Jefferies/Quantitative Execution Strategies (QES) UBS SJ Levinson & Sons Accounting Systems Advent APX Princeton ePAM Advent Axys Princeton Financial Systems/PAM, ePAM Advent Geneva Princeton PAM Citi Accounting Princeton PFI DST GPS SS&C Camra DST InfoQuest SS&C Pacer Eagle Investment Systems/Eagle STAR Thomson Reuters PORTIA IDS GIM 2 Wall Street Office Metavante Equity Algo Trading Abel/Noser (US) Credit Suisse (Global) Aqua Securities, L.P (US) Daiwa Capital Securities Markets Co. Ltd (APAC) Auerbach Grayson (Global) Dash Financial (US) Barclay’s Capital (Global) Deutsche Bank (Global) BestEx Pty Ltd DnB NOR Bank ASA (EU,UK) BMO Capital Markets Corp Drexel Hamilton LLC BMO Nesbitt Burns DZ BANK AG (EU) BNP Paribas (Global) Exane (US,EU,UK) BTIG, LLC (US) Execution Ltd (UK) Canaccord Capital (Global) Fidelity Capital Markets (US) CIBC World Markets (US, CAN) FOX River Execution (US) CIMB Securities (Singapore) Pte Ltd (Global) Goldman Sachs (Global) Citigroup (Global) Guggenheim Securities LLC (US) Clearpool, Group (US) HSBC (Global) CLSA Limited (Global) Instinet (Global) Commonwealth Securities, Ltd (Global) ISI Group (US) ConvergEx Execution Solutions (US) ITG Inc. (Global) Cowen & Company, LLC. (US) Jefferies & Company (US) 1 Interfaces & Partners Equity Algo Trading (cont’d) JP Morgan (Global) Quantitative Brokers, LLC (US) Knight Securities (US) Raymond James (US) Leerink Swann & Co. -

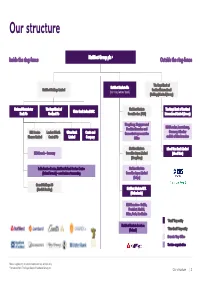

Our Structure

Our structure Inside the ring -fence NatWest Group plc 1 Outside the ring -fence The Royal Bank of NatWest Markets Plc NatWest Holdings Limited Scotland International (non ring-fenced bank) (Holdings) Limited (Jersey) National Westminster The Royal Bank of NatWest Markets The Royal Bank of Scotland Ulster Bank Ireland DAC Bank Plc Scotland Plc Securities Inc. (USA) International Limited (Jersey) Hong Kong, Singapore and Frankfurt Branches and RBSI London, Luxembourg, RBS Invoice Lombard North Ulster Bank Coutts and Connecticut representative Guernsey, Gibraltar Finance Limited Central Plc Limited Company Office and Isle of Man branches NatWest Markets Isle of Man Bank Limited EEA Branch – Germany Securities Japan Limited (Isle of Man) (Hong Kong) India Service Centre, NatWest Poland Service Centre NatWest Markets (Poland branch) – non -business transacting Securities Japan Limited (Tokyo) Strand Holdings AB (Nordisk Renting) NatWest Markets N.V. (Netherlands) EEA Branches – Dublin, Frankfurt, Madrid, Milan, Paris, Stockholm “Bank” key entity NatWest Markets Services (Poland) “Non -Bank” key entity Branch / Rep Office Service organisation Notes: Legal entity structure represents key entities only. 1 Renamed from The Royal Bank of Scotland Group plc. Our structure │ 1 This structure has been prepared for information purposes only and does not constitute a full Group structure chart or an analysis of all potentially material issues and is subject to change at any time without prior notice. NatWest Markets does not undertake to update you of such changes. NatWest Markets Plc is registered in Scotland No. 90312 with limited liability. Registered Office: 36 St Andrew Square, Edinburgh EH2 2YB. Authorised by the Prudential Regulation Authority and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority and the Prudential Regulation Authority. -

Royal Bank of Scotland PMI®

Embargoed until 0001, Monday 17th May 2021 Royal Bank of Scotland PMI® Scottish economy sees further growth in April • Further upturn in activity, with rate of growth quickening since March • New business rises for first time since August 2020 • Firms begin hiring amid growing capacity pressures The Scottish economy continued on its recovery path in April, according to the latest Royal Bank of Scotland PMI®. The seasonally adjusted headline Royal Bank of Scotland Business Activity Index - a measure of combined manufacturing and service sector output - rose from 54.3 March to 55.4 in April to signal a back-to-back upturn, with the rate of growth the quickest for eight months. Central to the expansion was a renewed rise in new work, with the rate of increase the fastest for nearly three years and solid. According to panellists, client demand had improved noticeably amid loser lockdown restrictions. Subsequently, capacity pressures built in April as backlogs of work rose for the first time in over two-and-a-half years. In response, firms took on additional staff for the first time since January 2020. April data highlighted the first increase in new business at Scottish private sector firms for eight months. Panellists linked the rise to improved client demand, driven in part by the easing of lockdown measures. Moreover, the upturn in new work was the strongest since August 2018, with both manufacturers and services firms registering an increase. Nonetheless, the rate of growth in Scotland lagged behind the UK average in April. Of the 12 monitored areas, only the North East of England saw a slower expansion of new business than Scotland. -

The Royal Bank of Scotland Group Plc 22 May 2020 Update Post 1Q Results

FINANCIAL INSTITUTIONS CREDIT OPINION The Royal Bank of Scotland Group plc 22 May 2020 Update post 1Q results Update Summary Rating Rationale The long-term senior unsecured debt rating of The Royal Bank of Scotland Group plc (RBSG) is Baa2 with a positive outlook. RBSG's baa2 Baseline Credit Assessment (BCA) is driven by: (1) its strong capital position, which is higher than that of its peers and above its own target; (2) strong retail and corporate RATINGS franchises which mitigate ongoing pressures on revenue and credit impairments due Domicile Edinburgh, United to Corponavirus-led weak economic environment; (3) its improved risk framework and Kingdom governance; and 4) its exposure to more volatile, complex and loss-making capital markets Long Term CRR Not Assigned activities. Long Term Debt Baa2 Type Senior Unsecured - Fgn RBSG is the ultimate parent and holding company of the ring-fenced operating company Curr Outlook Positive National Westminster Bank plc (NatWest Bank; baa1; A2 positive) and of the non-ring- Long Term Deposit Not Assigned fenced operating company NatWest Markets Plc (NatWest Markets, formerly RBS plc; ba2; Baa2 positive). Please see the ratings section at the end of this report for more information. The ratings and outlook shown Exhibit 1 reflect information as of the publication date. Rating Scorecard - Key Financial Ratios1 RBSG (BCA: baa2) Median baa2-rated banks 25% 45% Contacts 40% 20% 35% Alessandro Roccati +44.20.7772.1603 Factors Liquidity 30% Senior Vice President 15% 25% [email protected] -

The Royal Bank of Scotland Group Plc

The Royal Bank of Scotland Group plc Pre-close Trading Update The Royal Bank of Scotland Group (RBS) will be holding discussions with analysts and investors ahead of its close period for the year ending 31 December 2004. This statement sets out the information that will be covered in those discussions. RBS has continued to make good progress in 2004. Key features of its annual results, which will be released on 24 February 2005, are expected to include strong income growth (both organic and from acquisitions) across a broad mix of businesses, improved efficiency and continued improvements in credit metrics. Consequently, the Group is confident of meeting market expectations. Income and Margins RBS has maintained strong momentum in organic income growth in the second half of the year, supported by continued good growth in loans and deposits, stable interest margins and good growth in non-interest income. Strong growth in income has been achieved despite the impact of US dollar weakness. The Group has continued to achieve good growth in assets, including a sustained strong performance in small and mid-corporate loans, some recovery in demand for large corporate loans and continued growth in consumer lending, particularly mortgages. In UK consumer lending, there have been some signs of a modest easing in the rate of growth in unsecured lending and, more recently, in mortgages. UK consumer lending accounts for only 10% of Group income, so any slowdown would have minimal impact on our overall income. Deposit balances have continued to grow across the Group, with particularly good growth in corporate volumes. -

Scotland Analysis: Financial Services and Banking

Scotland analysis: financial services and banking Calculating the size of the Scottish banking sector relative to Scottish GDP The Treasury’s paper Scotland analysis: financial services and banking outlines that: • Banking sector assets for the whole UK at present are around 492 per cent of GDP. • The Scottish banking sector, by comparison, would be extremely large in the event of independence. It currently stands at around 1254 per cent of Scotland’s GDP. Data on total assets of the Scottish financial sector was provided to the Treasury by the Financial Services Authority (FSA), which was the regulator of all UK financial services firms up until 1 April 2013, when it was replaced by the Prudential Regulation Authority (PRA) and Financial Conduct Authority (FCA). As the paper sets out, the analysis proceeds on the basis that firms whose headquarters or principal place of business are in Scotland are to be considered ‘Scottish’ firms. Further information about where individual firms are located is available from the financial services register, which is available from www.fca.org.uk/register/ When considering groups, legal entities are treated on an individual basis, rather than the whole group being classified as either Scottish or ‘rest of the UK’. For example within RBS group, Royal Bank of Scotland PLC is treated as a Scottish firm, but National Westminster Bank PLC is treated as a ‘rest of the UK’ firm: although it is part of RBS group, it is separately authorised and headquartered in London. The regulator is not able to provide data for publication about the size of assets held by individual firms, as there are restrictions on the sharing of firm-specific regulatory data. -

Royal Bank of Scotland Settlement Agreement

CANADIAN FOREX CLASS ACTION NATIONAL SETTLEMENT AGREEMENT TABLE OF CONTENTS RECITALS .....................................................................................................................................1 SECTION 1 - DEFINITIONS .......................................................................................................4 SECTION 2 - SETTLEMENT APPROVAL ............................................................................10 2.1 Best Efforts ............................................................................................................10 2.2 Motions Seeking Approval of Notice and Certification or Authorization .............11 2.3 Motions Seeking Approval of the Settlement ........................................................11 2.4 Pre-Motion Confidentiality ....................................................................................12 SECTION 3 - SETTLEMENT BENEFITS ...............................................................................12 3.1 Payment of Settlement Amount .............................................................................12 3.2 Taxes and Interest ..................................................................................................13 3.3 Intervention in the U.S. Litigation .........................................................................13 SECTION 4 – COOPERATION ................................................................................................14 4.1 Extent of Cooperation ............................................................................................14