Nerve and Knowledge Book Excerpt

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Evolution of Sherlock Holmes: Adapting Character Across Time

The Evolution of Sherlock Holmes: Adapting Character Across Time and Text Ashley D. Polasek Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY awarded by De Montfort University December 2014 Faculty of Art, Design, and Humanities De Montfort University Table of Contents Abstract ........................................................................................................................... iv Acknowledgements .......................................................................................................... v INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................... 1 Theorising Character and Modern Mythology ............................................................ 1 ‘The Scarlet Thread’: Unraveling a Tangled Character ...........................................................1 ‘You Know My Methods’: Focus and Justification ..................................................................24 ‘Good Old Index’: A Review of Relevant Scholarship .............................................................29 ‘Such Individuals Exist Outside of Stories’: Constructing Modern Mythology .......................45 CHAPTER ONE: MECHANISMS OF EVOLUTION ............................................. 62 Performing Inheritance, Environment, and Mutation .............................................. 62 Introduction..............................................................................................................................62 -

William S. Baring-Gould Was a Time Executive Whose Contributions to the Literary World (And Especially to Sherlockians) Are Manifest

Honorary Member, Emeritus photo courtesy of Bill Vande Water William Stuart Baring-Gould 1913-1967 William S. Baring-Gould was a Time executive whose contributions to the literary world (and especially to Sherlockians) are manifest. Mr. Baring-Gould was a descendent of the well-known author and archivist Reverend Sabine Baring-Gould (1834-1924) who was a featured character in Laurie King's book The Moor. He was the author of numerous important Sherlockian works including, Sherlock Holmes of Baker Street, The Chronological Holmes and the famous The Annotated Sherlock Holmes. The Annotated Sherlock Holmes is considered by many Sherlockians as his crowning achievement and is a must in every Sherlock Holmes Collection. He authored other works, including The Lure of the Limerick: An Uninhibited History, Nero Wolfe of West Thirty-fifth Street (a work about the detective whom some speculate is the "son" of Sherlock Holmes) and collaborated with his wife, Ceil, onThe Annotated Mother Goose, Nursery Rhymes Old and New. All of these works are important volumes in their respective literary worlds. Mr. Baring-Gould was BSI and invested as "The Gloria Scott". Julian Wolfe said at his passing: "In the true Irregular tradition, and in accordance with the precepts of Christopher Morley, he was always ready to encourage young Sherlockians, many of whom owe much to his valuable asistance." Sherlockian.Net: William S. Baring-Gould Bill Baring-Gould, 1913-1967 W. S. Baring-Gould was an executive of Time Inc. and a distinguished though modest Sherlockian (invested in the Baker Street Irregulars as "The Gloria Scott", 1952). -

Roger Johnson, Mole End, 41 Sandford Road, Chelmsford CM2 6DE E-Mail: [email protected] No

THE NEWSLETTER OF THE SHERLOCK HOLMES SOCIETY OF LONDON Roger Johnson, Mole End, 41 Sandford Road, Chelmsford CM2 6DE e-mail: [email protected] no. 300 2nd February 2010 Welcome to the 300th issue! Thanks to Nicholas Briggs and his he did throw himself into local affairs as well, quickly becoming active colleagues at Big Finish (PO Box 3787, Maidenhead, Berkshire, SL6 in the Upper Norwood Literary & Scientific Society and Norwood 3TF; http://www.bigfinish.com/ranges/sherlock-holmes ) we can mark Cricket Club. He also, no less significantly, joined the Society for this anniversary with yet another prize competition. Two of you can win Psychical Research. Alistair Duncan is one of a distinguished little a copy of the third Big Finish Sherlock Holmes CD set, Holmes and the group whose work takes us just a little closer towards a complete Ripper by Brian Clemens, with Mr Briggs himself as the great portrait of the man who created Sherlock Holmes. He writes well, too. detective. (He had a very successful run in the same play a year ago at I’m delighted to recommend his book. the Theatre Royal, Nottingham.) Just name two films in which Sherlock MX Publishing has two special offers for members of the Sherlock Holmes investigates the Ripper murders. Send answers to me by 1 Holmes Society of London. You can buy all three of Alistair Duncan’s March, and the two correct answers drawn from the hat will win the books ( Eliminate the Impossible , Close to Holmes and The Norwood CDs. Holmes and the Ripper will be released in March, at £14.99. -

Ebsj-Sample.Pdf

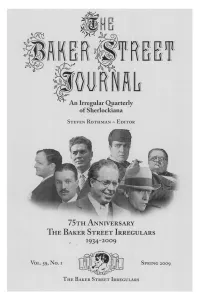

G E P4 \ e # An Irregular Quarterly of Sherlockiana STEVEN ROTHMAN EDITOR 75TH ANNIVERSARY THE BAKER STREET IRREGULARS 1934-2009 - "I's- ti 0 VOL. 59, No I SPRING 2009 ;a. THE BAKER STREET IRREGULARS Cover Illustration Key In honor of the 75th Anniversary of The Baker Street Irregulars our cover illustration features a montage of personalities who attended the very first dinner in 1934. 1. Christopher Morley; 2. H.W. Bell; 3. Vincent Starrett; 4. Basil Davenport; 5. Gene Tunney; 6. William Gillette; 7. Alexander Woollcott Volume 59 Number 1 Spring 2009 An Irregular Quarterly of Sherlockiana Founded by EDGAR W. SMITH Continued by JULIAN WOLFF, M.D. "Si monumentum quaeris, circumspice" Editor: STEVEN ROTHMAN Published by THE BAKER STREET IRREGULARS Copyright 2009 by THE BAKER STREET IRREGULARS All rights reserved LC 49-17066 ISSN 0005-4070 The appearance of the code following this statement indicates the copyright owner's consent that copies of articles in this journal may be made for personal or internal use, or for the personal internal use of specific clients. The consent is given on the condition, however, that the copier pay the stated per-copy fee to the Copyright Clearance Center, Inc., 21 Congress Street, Salem, MA 01970, for copying beyond that permitted by law including sections 107 and 109 of the United States Copyright Act. This consent does not extend to other kinds of copying, such as copying for general distribution, for advertising or promotional purposes, for creating new collective works, or for resale. Users should employ the following code when reporting copying from this issue to the Copyright Clearance Center: 0005 4070/91/$1.00 Articles in the JOURNAL are regularly indexed in Humanities International Complete (HIC). -

The Shaw One Hundred

The Basic Holmesian Library A Catalog by Timothy J. Johnson In conjunction with an exhibit based on John Bennett Shaw's list of One Hundred and a conference sponsored by The Norwegian Explorers of Minnesota Elmer L. Andersen Library Special Collections & Rare Books University of Minnesota Libraries June — July 2001 Minneapolis 2001 Introduction to the Exhibit “Some years ago I staged an exhibition of what I then considered to be the One Hundred Basic Books, pamphlets and periodicals relating to Sherlock Holmes.” So wrote John Bennett Shaw in a short introduction to his first official compilation of these books, pamphlets and periodicals, which he titled “The Basic Holmesian Library”. His goal was to give “an in-depth view of the entire Holmesian culture,” and while he admitted the difficulty encountered in choosing what to include out of so many fine writings, he approached this daunting task with the enthusiasm of one who truly understood the meaning of Collecting Sherlockiana. His own library, which he defined in his essay “Collecting Sherlockiana” as “…a number of books and other printed material on one subject, or on several,” focused on Sherlock Holmes. An avid bibliophile, he narrowed his collecting to this one subject after donating his other collections to such universities as Notre Dame, Tulsa, and the University of New Mexico. It is perhaps ironic to use the term narrowed for such a collection, which grew to over 15, 000 items. As his own library expanded with acquisitions of previously printed as well as newly published items, he revised his list of the Basic Holmesian Library. -

The District Messenger

THE DISTRICT MESSENGER The Newsletter of the Sherlock Holmes Society of London Roger Johnson, Mole End, 41 Sandford Road, Chelmsford CM2 6DE no. 158 4th March 1996 If your subscription is due for renewal, please send several stamped & self- addressed envelopes, or (overseas) send £5.00 or US$10.00 for 12 issues. Dollar checks should be payable to Jean Upton. The Metropolitan Toronto Reference Library (c/o George A. Vanderburgh, PO Box 204, 420 Owen Sound Street, Shelburne, Ontario L0N 1S0, Canada) has published an excellent collection of essays: FroFromm Baltimore to Baker Street; Thirteen Sherlockian Studies by William Hyder. The author cuts through the accretion of error and fantasy that has bogged down Holmesian scholarship since before the days of Vincent Starrett, and presents well-researched, well-reasoned and intensely readable papers on Holmes' musical ability, Watson's education and career, religious figures in the Canon, and more. His investigation of the Abernetty business and of what he calls "The Martha Myth" are models of their kind. There's really funny humour in "The Root of the Matter" and "The Detectives of Penzance", and the two short plays are so good that I want to see them performed ("The Impression of a Woman" is admittedly similar to David Stuart Davies' Sherlock Through the Magnifying GlassGlass, though neither could have influenced the other). Look, this one's really good, and every home should have a copy. It's a nice 216-page hardback, costing £15.00 + £2.00 postage. Cheques should be payable to George A. Vanderburgh. The Baker Street Irregulars have published IrregularIrregular Proceedings of the Mid 'Forties'Forties, edited by Jon L. -

The Wicked Beginnings of a Baker Street Classic!

The Wicked Beginnings of a Baker Street Classic! by Ray Betzner From The Baker Street Journal Vol. 57, No. 1 (Spring 2007), pp. 18 - 27. www.BakerStreetJournal.com The Baker Street Journal continues to be the leading Sherlockian publication since its founding in 1946 by Edgar W. Smith. With both serious scholarship and articles that “play the game,” the Journal is essential reading for anyone interested in Sherlock Holmes, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, and a world where it is always 1895. www.BakerStreetJournal.com THE WICKED BEGINNINGS OF A BAKER STREET CLASSIC! by RAY BETZNER In the early 1930s, when pulps were the guilty pleasures of the American maga- zine business, Real Detective was just another bedsheet promising sex, sin, and sensationalism for a mere two bits. With a color cover that featured a sultry moll, a gun-toting cop, or a sneering mobster, it assured the reader that when he got the magazine back to his garage or basement, he would be entertained by the kind of delights not found in The Bookman or The Atlantic Monthly. And yet, for a moment in December 1932, a single article featuring the world’s first consulting detective elevated the standards of Real Detective to something approaching respectability. Starting on page 50, between “Manhattan News Flash” (featuring the kidnapping of little John Arthur Russell) and “Rah! Rah! Rah! Rotgut and Rotters of the ’32 Campus” (by Densmore Dugan ’33) is a three-quarter-page illustration by Frederic Dorr Steele showing Sherlock Holmes in his dressing gown, standing beneath the headline: “Mr. Holmes of Baker Street: The Discovery of the Great Detective’s Home in London.” Com- pared with “I am a ‘Slave!’ The Tragic Confession of a Girl who ‘Went Wrong,’” the revelations behind an actual identification for 221B seems posi- tively quaint. -

Sherlock Holmes for Dummies

Index The Adventure of the Eleven Cuff-Buttons • Numerics • (Thierry), 249 221b Baker Street, 12, 159–162, 201–202, “The Adventure of the Empty House,” 301, 304–305 21, 48, 59, 213, 298 “The Adventure of the Engineer’s Thumb,” 20, 142 • A • “The Adventure of the Golden Pince-Nez,” 22, 301 “The Abbey Grange,” 22 “The Adventure of the Illustrious Client,” Abbey National, 162 24, 48, 194–195, 309 acting, Sherlock Holmes’s, 42. See also “The Adventure of the Lion’s Mane,” 24, 93 individual actors in roles “The Adventure of the Mazarin Stone,” Adler, Irene (character), 96, 280, 298 24, 159 “The Adventure of Black Peter,” 22 “The Adventure of the Missing Three- “The Adventure of Charles Augustus Quarter,” 22 Milverton,” 22, 137, 267 “The Adventure of the Noble Bachelor,” “The Adventure of Shoscombe Old 20, 308 Place,” 25 “The Adventure of the Norwood “The Adventure of the Abbey Grange,” 22 Builder,” 21 “The Adventure of the Beryl Coronet,” “The Adventure of the Priory School,” 22 20, 141 “The Adventure of the Red Circle,” “The Adventure of the Blanched 23, 141, 188 Soldier,” 24, 92, 298 “The Adventure of the Reigate Squire,” 20 “The Adventure of the Blue Carbuncle,” “The Adventure of the Retired 19, 141, 315 Colourman,” 25 “The Adventure of the Bruce-Partington “The Adventure of the Second Stain,” 22, 78 Plans,” 23 “The Adventure of the Six Napoleons,” “The Adventure of the Cardboard Box,” 22, 73 20, 97, 138, 189, 212 “The Adventure of the Solitary Cyclist,” “The Adventure of the Copper Beeches,” 21, 137, 140 20, 140 “The Adventure of the Speckled -

THE NEWSLETTER of the SHERLOCK HOLMES SOCIETY of LONDON Dr

THE NEWSLETTER OF THE SHERLOCK HOLMES SOCIETY OF LONDON http://www.sherlock-holmes.org.uk/ Dr. Carrie Parris e-mail: [email protected] Twitter: @SHSLondon Facebook: www.facebook.com/TheSherlockHolmesSocietyofLondon no. 358 21 February 2016 March is almost upon us, but you will have to control your Elaine also had the pleasure of awarding Honorary ardour for the Society’s first spring meeting this year as it will Membership to Philip Porter. Elaine said: ‘Philip has the take place a little later than usual on 6 April 2016. The focus distinction of having served as a Chairman of the Society for will be on ‘The Abbey Grange,’ and members will receive two terms, a feat only matched by our founding father Tony information on bookings in due course. See our website for Howlett. He also took on the truly onerous job of portraying more information: http://goo.gl/n8uFSS. Sherlock Holmes on four Swiss trips and one jaunt round the vineyards and cognac fields of France, a trip which he also The dates for our cricket matches this year have also been organised.’ He has also organised excursions and events - confirmed: 30 April 2016 v Eton College Strawberry XI notably the ‘Back to Baker Street Festival’ in 1994 - and (2pm) at Eton; and 2 July 2016 v PG Wodehouse Soc through his contacts he introduced the Society to the House of (11.30am) at West Wycombe Cricket Ground, Commons for the Annual Dinner. In his spare time he has Buckinghamshire. Members and guests are all welcome been a racing driver, balloon pilot and airship pilot. -

Sherlock Holmes C O L L E C T I O

September 2000 D S O F N Volume 4 Number 3 E T Remembrances I H R In supporting the Sherlock Holmes Collections, many donors have made contributions either in honor or in memory of special per- E sons. Due to the number of people who made donations in Mac McDiarmid’s memory, we will list them as one group. F IN HONOR OF FROM Anonymous Ted Friedman Nancy Beiman Laura Kuhn Dr. Howard Burchell Richard M. Caplan Bob Burr Laura Kuhn Sherlock Holmes Mark Conrad Laura Kuhn COLLECTIONS "The Insoluble Puzzles" Laura Kuhn Carole McCormick Laura Kuhn “Your merits should be publicly recognized” (STUD) Austin McLean Charles Press Bob Thomalen Paul Singleton 221Beach Alexian Gregory photo by Julie McKuras Peter Blau, Mac McDiarmid, Michael Whelan Contents Some Personal Recollections of the Early August 1998 Founders' Footprints Conference IN MEMORY OF FROM Some Personal Days of the Sherlock Holmes Collections Errett W. McDiarmid Cheryl Anderson, Thomas Arlander, Pauline Cartford, Mary Cermak, Recollections of the Early By Andrew Malec, B.S.I. Susan Davern, Wendell and Marjorie DeBoer, Frank and Genevieve Di Gangi, Days of the Sherlock Pj Doyle, Karen Ellery, Joan Fabian, Aurelio and Marana Floria, Paul and Ruth Holmes Collections am pleased to be afforded this undergraduate days. I attended my initial Fonstad, Lisl Gaal, Alma Gaona, Belen Gaona-Keithley, Thomas and Lynda Garnett, opportunity to draw together some Norwegian Explorers meeting in 1975 Dennis and Caroline Gebhard, David Hammer, Robert Holloway, Karen Hoyle, 1 of my earliest memories of the (on the occasion of John Bennett Shaw’s Margaret S. -

Download Issue

THE DISTRICT MESSENGER The Newsletter of the Sherlock Holmes Society of London Roger Johnson, Mole End, 41 Sandford Road, Chelmsford CM2 6DE no. 159 15th April 1996 To renew your subscription, send 12 stamped, self-addressed envelopes, or (overseas) send 12 International Reply Coupons or £5.00 or US$10.00 for 12 issues. Dollar checks should be payable to Jean Upton. (Warning: British postal rates are due to rise sometime shortly.) Kathryn White ("The Musgrave Ritual" BSI) and David Stuart Davies ("Sir Ralph Musgrave" BSI) were married at Haworth on Saturday the 6th April, in the presence of many Sherlockian friends. Congratulations! Patricia E. Moran ("Patience Moran" BSI) died on 12th March, after a long period of illness, necessitating several operations. A founder of the Adventuresses of Sherlock Holmes, and editor of the ASH journal, The Serpentine MuseMuse, Pat was also good company and a good friend. The BSI History Project is undoubtedly Jon L. Lellenberg's magnum opusopus. Now we have the fourth volume, Irregular Proceedings of the Mid 'Forties (The Baker Street Irregulars, The Baker Street Journal, P.O. Box 465, Hanover, PA 17331, USA). It's engrossing reading for anyone interested in the world of Sherlockians and their activities, drawing on an apparently immense archive of correspondence and other documents. Smith, Morley, Starrett, Steele, Stout, Davenport, Wolff etetet alalal.al - these are the people who founded our Great Game, finding out as they went along what could be done (sometimes at great financial cost, as in Ben Abramson's case). This period from 1944 to 1947 saw the publication of seminal books (by Edgar W. -

Bibliography

BIBLIOGRAPHY Aaron, Michele, Death and the Moving Image: Ideology, Iconography and I. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2015. Ebook. Agane, Ayaan. “Confations of ‘Queerness’ in 21st Century Adaptations.” In Gender and the Modern Sherlock Holmes: Essays on Film and Television Adaptations since 2009, edited by Nadine Farghaly, 160–173. Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2015. Alberto, Maria. “‘Of dubious and questionable memory’: The Collision of Gender and Canon in Creating Sherlock’s Postfeminist Femme Fatale.” In Gender and the Modern Sherlock Holmes: Essays on Film and Television Adaptations since 2009, edited by Nadine Farghaly, 66–84. Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2015. Ali, Dhanil. The Curse of Sherlock Holmes. London: MX Publishing, 2013. Altschuler, Eric L. “Asperger’s in the Holmes Family.” Journal of Autism and Developmental Discord 43 (2013): 2238–2239. Andrews, Hannah. Television and British Cinema: Convergence and Divergence since 1990. Basingstoke: Palgrave, 2014. Apple History Channel. “Steve Jobs Stanford Commencement Speech,” Apple History Channel. YouTube. 2006. Accessed Sept 16, 2016. https://www. youtube.com/watch?v D1R-jKKp3NA. = Archer, William. “Masks or Faces?” In Actors on Acting, edited by Toby Cole and Helen Krich Chinoy, 74–86. New York: Crown, 1976. Asghar, Rob. “Five Reasons to Ignore the Advice to Do What You Love,” Forbes.com. 2013. Accessed Sept 16 2016. http://www.forbes.com/sites/ robasghar/2013/04/12/fve-reasons-to-ignore-the-advice-to-do-what-you- love/#cb38d9d36351. © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2017 235 B. Poore, Sherlock Holmes from Screen to Stage, Adaptation in Theatre and Performance, DOI 10.1057/978-1-137-46963-2 236 BIBLIOGRAPHY Associated Press.