The Wicked Beginnings of a Baker Street Classic!

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gillette Case Intrigues Renovators Author

GILLETTE CASE INTRIGUES RENOVATORS Associated Press lated over the years as one of the nation's leading actors. The resulting moisture problems haunted Gillette Most of Gillette's success had come from his portrayal, on long after the castle's completion by the renowned EAST HADDAM — Over the past two years, David stage and screen, of the fictional detective Sherlock Hartford firm of Porteus & Walker. And they continue Barkin has found himself investigating a mortar mys- Holmes, from the novels by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. to this day, as workers feverishly rebuild stone walls tery perhaps only Sherlock Holmes could unravel. surrounding the castle and administrators prepare Barkin, a New Haven architect, has been lurking in a Gillette Castle — closed now for nearly three years as it and the surrounding 184 acres of state park grounds plans for a visitor's center, new exhibits and the re- damp and musty castle, muttering things like, "What introduction of Gillette's famed miniature railroad. did he mean here?" as he uncovers mustard, green, red, undergo a $10.1 million restoration and improvement program — had been intended by its eccentric first Most of the improvements will coincide with the cas- black and burgundy mortar — the gooey material that, tle's planned reopening on Memorial Day weekend once dry, holds stone walls together. owner to resemble a ruin on the Rhine River in Germa- ny. Part of the aesthetic, massive fieldstone walls un- "He had a leaking castle from the day he built it," PLEASE SEE GILLETTE, PAGE B5 Barkin says of William Gillette, the man who designed dulate unevenly, allowing water to pool in certain and paid nearly $1 million for the castle in 1919, using areas — especially around the windows, which display his ripe imagination and the money he had accumu- evidence of awnings once having been deployed. -

Sherlock Holmes: the Final Adventure the Articles in This Study Guide Are Not Meant to Mirror Or Interpret Any Productions at the Utah Shakespeare Festival

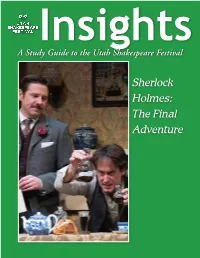

Insights A Study Guide to the Utah Shakespeare Festival Sherlock Holmes: The Final Adventure The articles in this study guide are not meant to mirror or interpret any productions at the Utah Shakespeare Festival. They are meant, instead, to be an educational jumping-off point to understanding and enjoying the plays (in any production at any theatre) a bit more thoroughly. Therefore the stories of the plays and the interpretative articles (and even characters, at times) may differ dramatically from what is ultimately produced on the Festival’s stages. The Study Guide is published by the Utah Shakespeare Festival, 351 West Center Street; Cedar City, UT 84720. Bruce C. Lee, communications director and editor; Phil Hermansen, art director. Copyright © 2014, Utah Shakespeare Festival. Please feel free to download and print The Study Guide, as long as you do not remove any identifying mark of the Utah Shakespeare Festival. For more information about Festival education programs: Utah Shakespeare Festival 351 West Center Street Cedar City, Utah 84720 435-586-7880 www.bard.org. Cover photo: Brian Vaughn (left) and J. Todd Adams in Sherlock Holmes: The Final Adventure, 2015. Contents Sherlock InformationHolmes: on the PlayThe Final Synopsis 4 Characters 5 About the AdventurePlaywright 6 Scholarly Articles on the Play The Final Adventures of Sherlock Holmes? 8 Utah Shakespeare Festival 3 351 West Center Street • Cedar City, Utah 84720 • 435-586-7880 Synopsis: Sherlock Holmes: The Final Adventure The play begins with the announcement of the death of Sherlock Holmes. It is 1891 London; and Dr. Watson, Holmes’s trusty colleague and loyal friend, tells the story of the famous detective’s last adventure. -

Australian SF News 28

NUMBER 28 registered by AUSTRALIA post #vbg2791 95C Volume 4 Number 2 March 1982 COW & counts PUBLISH 3 H£W ttOVttS CORY § COLLINS have published three new novels in their VOID series. RYN by Jack Wodhams, LANCES OF NENGESDUL by Keith Taylor and SAPPHIRE IN THIS ISSUE: ROAD by Wynne Whiteford. The recommended retail price on each is $4.95 Distribution is again a dilemna for them and a^ter problems with some DITMAR AND NEBULA AWARD NOMINATIONS, FRANK HERBERT of the larger paperback distributors, it seems likely that these titles TO WRITE FIFTH DUNE BOOK, ROBERT SILVERBERG TO DO will be handled by ALLBOOKS. Carey Handfield has just opened an office in Melbourne for ALLBOOKS and will of course be handling all their THIRD MAJIPOOR BOOK, "FRIDAY" - A NEW ROBERT agencies along with NORSTRILIA PRESS publications. HEINLEIN NOVEL DUE OUT IN JUNE, AN APPRECIATION OF TSCHA1CON GOH JACK VANCE BY A.BERTRAM CHANDLER, GEORGE TURNER INTERVIEWED, Philip K. Dick Dies BUG JACK BARRON TO BE FILMED, PLUS MORE NEWS, REVIEWS, LISTS AND LETTERS. February 18th; he developed pneumonia and a collapsed lung, and had a second stroke on February 24th, which put him into a A. BERTRAM CHANDLER deep coma and he was placed on a respir COMPLETES NEW NOVEL ator. There was no brain activity and doctors finally turned off the life A.BERTRAM CHANDLER has completed his support system. alternative Australian history novel, titled KELLY COUNTRY. It is in the hands He had a tremendous influence on the sf of his agents and publishers. GRIMES field, with a cult following in and out of AND THE ODD GODS is a short sold to sf fandom, but with the making of the Cory and Collins and IASFM in the U.S.A. -

Mystery on Baker Street

MYSTERY ON BAKER STREET BRUTAL KAZAKH OFFICIAL LINKED TO £147M LONDON PROPERTY EMPIRE Big chunks of Baker Street are owned by a mysterious figure with close ties to a former Kazakh secret police chief accused of murder and money-laundering. JULY 2015 1 MYSTERY ON BAKER STREET Brutal Kazakh official linked to £147m London property empire EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The ability to hide and spend suspect cash overseas is a large part of what makes serious corruption and organised crime attractive. After all, it is difficult to stuff millions under a mattress. You need to be able to squirrel the money away in the international financial system, and then find somewhere nice to spend it. Increasingly, London’s high-end property market seems to be one of the go-to destinations to give questionable funds a veneer of respectability. It offers lawyers who sell secrecy for a living, banks who ask few questions, top private schools for your children and a glamorous lifestyle on your doorstep. Throw in easy access to anonymously-owned offshore companies to hide your identity and the source of your funds and it is easy to see why Rakhat Aliyev. (Credit: SHAMIL ZHUMATOV/X00499/Reuters/Corbis) London’s financial system is so attractive to those with something to hide. Global Witness’ investigations reveal numerous links This briefing uncovers a troubling example of how between Rakhat Aliyev, Nurali Aliyev, and high-end London can be used by anyone wanting to hide London property. The majority of this property their identity behind complex networks of companies surrounds one of the city’s most famous addresses, and properties. -

Li^^Ksehtarions

PAGE 4 THE INDIANAPOLIS TIMES JAN. 15, 1936 Louise Essex Proves Idea Coming ,Here Friday on Screens and Stage of Moving Picture Theaters Thrills and That Musicians of State Chills Make Rank With World's Finest Movie Short Cellist, Appearing With Indianapolis Symphony, Presents Graphic Newsreel Pictures Saint-Saens Concerto, Bringing to Authority, It Catch Tragedy as Depth of Feeling, Fluent Dexterity. It Stalks. BY JAMES THRASHER This week has brought us two exceptional performances bv Indian- When a newsreel cameraman goes apolis musicians. They should help to dispel the false, but still prevalent, after his story he usually geta it. notion that the soil of artistic growth Is confined to continental Europe. But he also gets more than the Louise Essex, cellist and soloist with the Indianapolis Symphony Orches- censors or editors will allow in the tra last night, reaffirmed the impression created by Bomar Cramer's piano final reel. recital Sunday—that one may ascend the slopes of Parnassus from the What is left over is saved, and prairies of Indiana. some of the most interesting of theae Miss Essex delayed her debut in excerpts from the world’s pictorial public recital until last night, history are to be shown as “Camera though she had gained an enviable Thrills,” at the Circle beginning reputation in Europe and our East- Blueprints Friday. ern cities. It seems a wise decision, Aid Charles E. Ford, head of Universal for she came to us as a well- Newsreel, sponsored in Indianapolis equipped and gifted musician with- by Tiie Times, has arranged these out deficiencies which local pride in Film-Making many scenes of action and real life might seek to excuse. -

Elementary, My Dear Readers

NEW ORLEANS NOSTALGIA Remembering New Orleans History, Culture and Traditions By Ned Hémard Elementary, My Dear Readers NCIS (which stands for Naval Criminal Investigative Service) is an extremely popular “police procedural” television drama that has spun off as a New Orleans series. NCIS: New Orleans, which airs Tuesday nights on CBS, is set in the Crescent City and it would be highly unusual if you haven’t seen the show filming around town. It premiered on September 23, 2014. The episodes revolve around a fictional team of agents led by Special Agent Dwayne Cassius “King” Pride, Special Agent Christopher LaSalle, and Special Agent Meredith Brody. They handle criminal investigations involving the U.S. Navy and Marine Corps. If the NCIS team seems to be everywhere you look these days, allow yourself to travel back in literary time and imagine another famous detective team present all around you. Even if their bailiwick was late Victorian England, I seem to feel their presence all around this historic city. Perhaps you will, too. Arthur Conan Doyle penned his first Sherlock Holmes story, A Study in Scarlet, in novel form in 1886 at the age of 27. In it Holmes expounded: “Criminal cases are continually hinging upon that one point. A man is suspected of a crime months perhaps after it has been committed. His linen or clothes are examined and brownish stains discovered upon them. Are they blood stains, or mud stains, or rust stains, or fruit stains, or what are they? That is a question which has puzzled many an expert, and why? Because there was no reliable test. -

Convergence Culture Reconsidered

Reconsidering Transmedia(l) Worlds Nicole Gabriel, Bogna Kazur, and Kai Matuszkiewicz 1. Introduction “Any thoughtful study of contemporary transmedia must start with the vital caveat that transmedia is not a new phenomenon, born of the digital age.” (Jason Mittell 2014, 253; emphasis in the original) To begin with, we would like to agree with the general sentiment of Mittell’s statement: ‘transmedia,’ which Mittell seems to use as an abbreviation of the term ‘transmediality,’ is not a new phenomenon. But can it really be a mere coincidence that these two terms and other related concepts such as ‘transmedial worlds’ have been introduced and extensively discussed in academic discourses since the early 2000s, less than ten years after the introduction of home computers and the inter- net to numerous private households, and at about the same time as the Web 2.0 came into existence? We do not think so. Rather, we believe that the increasing research interest of media studies in these phenomena and the various concepts used in this research field are indicators of a fundamental change in (trans)media culture that is a result of the emergence of digital technologies as well as their mas- sive influence on our everyday lives. The aims of this paper are to take a closer look at the terminology used to de- scribe different phenomena in the field of transmedia studies, to differentiate be- tween these terms and concepts and render them more precise, and to put trans- media(l) worlds into a historical context through the analysis of three case studies: the transmedial universe of Sherlock Holmes, the Alien saga, and the transmedial world of The Legend of Zelda. -

The Evolution of Sherlock Holmes: Adapting Character Across Time

The Evolution of Sherlock Holmes: Adapting Character Across Time and Text Ashley D. Polasek Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY awarded by De Montfort University December 2014 Faculty of Art, Design, and Humanities De Montfort University Table of Contents Abstract ........................................................................................................................... iv Acknowledgements .......................................................................................................... v INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................... 1 Theorising Character and Modern Mythology ............................................................ 1 ‘The Scarlet Thread’: Unraveling a Tangled Character ...........................................................1 ‘You Know My Methods’: Focus and Justification ..................................................................24 ‘Good Old Index’: A Review of Relevant Scholarship .............................................................29 ‘Such Individuals Exist Outside of Stories’: Constructing Modern Mythology .......................45 CHAPTER ONE: MECHANISMS OF EVOLUTION ............................................. 62 Performing Inheritance, Environment, and Mutation .............................................. 62 Introduction..............................................................................................................................62 -

SF&F Newsletter Miller 1977-01

THE S F & F NEWSLETTER News/Info/Advertising Supplement to THE SF&F JOURNAL — (Vol. -2, #1; Whole y/16) Incorporating WASHINGTON S.F. NEWSLETTER '& part of THE JOURNAL SUPPLEMENT/SOTWJ Editor & Publisher: Don Miller - - - 300 ea., U/Sl.OO in U.S. -■-» - 3 Jan. *77 In This Issue — <| IN THIS ISSUE; IN BRIEF (Misc, notes/news/announcements); COLOPHON pg 1 ESFA REPORT: Minutes of ESFA Meetings of 11 & 12/76, by Allan Howard . pg 2 THE LCCAL SCENE: Misc. events coming up locally in January ........... pg 2 S.F. PARADE: Book Reviews, by David Bates, Stan Burns,- Jim Goldfrank, < I x Steve Lewis, Don Miller ................................................................................. 3-5 THE CON GAME: January, 1977 (incl. PRSFS meeting) .................. pg 5 ODDS & ENDS: More from Martin Wooster; The Local Scene (revisited); Miscellany (notes from Jon Coopersmith & T.L. Bohman) ............ pg 6 THE STEADY STREAM....: Of Books and Prozines Rec'd Thru 31/12/76 ..... pp 7-10 In Brief — Several changes taking place in the new year, with a year's experience under our belt with the new 'zines: (1) We have partially solved our publishing problem, with THE MYSTERY NOOK at least temporarily farmed out (anyone want to publish TSJ and/or TG?) and someone to do electrostencilling for us cheaply, but we still urgently need some way of getting our offset work with heavy blacks done cheaply, for covers & folios; (2) Including fanzine "reviews" in SFN and TSJ hasn't worked out; the for mer is too crowded, and the latter is too slow. So—THE JOURNAL SUPPLEMENT will come out bi-monthly, max. -

Exsherlockholmesthebakerstre

WRITTEN BY ERIC COBLE ADAPTED FROM THE GRAPHIC NOVELS BY TONY LEE AND DAN BOULTWOOD © Dramatic Publishing Company Drama/Comedy. Adapted by Eric Coble. From the graphic novels by Tony Lee and Dan Boultwood. Cast: 5 to 10m., 5 to 10w., up to 10 either gender. Sherlock Holmes is missing, and the streets of London are awash with crime. Who will save the day? The Baker Street Irregulars—a gang of street kids hired by Sherlock himself to help solve cases. Now they must band together to prove not only that Sherlock is not dead but also to find the mayor’s missing daughter, untangle a murder mystery from their own past, and face the masked criminal mastermind behind it all—a bandit who just may be the brilliant evil Moriarty, the man who killed Sherlock himself! Can a group of orphans, pickpockets, inventors and artists rescue the people of London? The game is afoot! Unit set. Approximate running time: 80 minutes. Code: S2E. “A reminder anyone can rise above their backgrounds and past, especially when someone else respectable also respects and trusts them.” —www.broadwayworld.com “A classic detective story with villains, cops, mistaken identities, subterfuge, heroic acts, dangerous situations, budding love stories and twists and turns galore.” —www.onmilwaukee.com Cover design: Cristian Pacheco. ISBN: 978-1-61959-056-4 Dramatic Publishing Your Source for Plays and Musicals Since 1885 311 Washington Street Woodstock, IL 60098 www.dramaticpublishing.com 800-448-7469 © Dramatic Publishing Company Sherlock Holmes: The Baker Street Irregulars By ERIC COBLE Based on the graphic novel series by TONY LEE and DAN BOULTWOOD Dramatic Publishing Company Woodstock, Illinois • Australia • New Zealand • South Africa © Dramatic Publishing Company *** NOTICE *** The amateur and stock acting rights to this work are controlled exclusively by THE DRAMATIC PUBLISHING COMPANY, INC., without whose permission in writing no performance of it may be given. -

Scuttlebutt from the Spermaceti Press 2021

Jan 21 #1 Scuttlebutt from the Spermaceti Press Sherlockians (and Holmesians) did not gather in New York to celebrate the Great Detective’s 167th birthday this year, but the somewhat shorter long weekend offered plenty of events, thanks to Zoom and other modern technol- ogy. Detailed reports will be available soon at the web-site of The Baker Street Irregulars <www.bakerstreetirregulars.com>, but here are few brief paragraphs to tide you over: The BSI’s Distinguished Speaker on Thursday was Andrew Lycett, the author of two fine books about Conan Doyle; his topic was “Conan Doyle’s Questing World” (and close to 400 people were able to attend the virtual lecture); the event also included the announcement by Steve Rothman, editor of the Baker Street Journal, of the winner of the Morley-Montgomery Award for the best article the BSJ last year: Jessica Schilling (for her “Just His Type: An Analysis of the Découpé Warning in The Hound of the Baskervilles”). Irregulars and guests gathered on Friday for the BSI’s annual dinner, with Andrew Joffe offering the traditional first toast to Nina Singleton as The Woman, and the program continued with the usual toasts, rituals, and pap- ers; this year the toast to Mrs. Hudson was delivered by the lady herself, splendidly impersonated by Denny Dobry from his recreation of the sitting- room at 221B Baker Street. Mike Kean (the “Wiggins” of the BSI) presented the Birthday Honours (Irregular Shillings and Investitures) to Dan Andri- acco (St. Saviour’s Near King’s Cross), Deborah Clark (Mrs. Cecil Forres- ter), Carla Coupe (London Bridge), Ann Margaret Lewis (The Polyphonic Mo- tets of Lassus), Steve Mason (The Fortescue Scholarship), Ashley Polasek (Singlestick), Svend Ranild (A “Copenhagen” Label), Ray Riethmeier (Mor- rison, Morrison, and Dodd), Alan Rettig (The Red Lamp), and Tracy Revels (A Black Sequin-Covered Dinner-Dress). -

S67-00104-N218-1995-07 08.Pdf

Issue 1218, July/August 1995 IN THIS ISSUE: SFRA INTERNAL AFFAIRS: President's Message (Sanders) 3 Minutes of Meeting Between Members of SmA and IAFA at the Annual ICFA (Gordon) 3 Corrections/Additions 4 SmA Members & Friends 5 Editorial (Sisson) 5 NEWS AND INFORMATION 7 SPECIAL FEATURE: "The Worlds of David Lynch": Lavery, David (Ed). Full of Secrets: Critical Approaches to 7Win Peaks. (Davis) 11 Gifford, Barry. Hotel Room Trilogy; and Lynch, David. David Lynch's Hotel Room. (umland) 13 SPECIAL FEATURE: "Lovecraft the Man": Lovecraft, H.P. (S.T. Joshi, Ed). Miscellaneous Writings. (Anderson) 17 Squires, Richard D. Stern Fathers 'neath the Mould: The Lovecraft Family in Rochester. (Bousfield) 20 Barlow, Robert H. and H.P. Lovecraft (S.T. Joshi, Ed). The Hoard of the Wizard Beast and One Other; and Joshi, S.T. & David schultz (Eds). H.P. Lovecraft Letters 7b SaJIlJel Loveman & vincent Starrett (Kaveny) 21 REVIEWS: Nonfiction: Barron, Neil (Ed). Anato~ Of Wonder, 4th Edition. (Kaveny & Bogstad) 23 Heller, Steven and Seynour Chwast. Jackets Required: An Illustrated History of American Book Jacket Design, 1920-1950. (Barron) 27 Kessler, carol Farley. Charlotte Perkins Gilman: her progress toward utopia with selected writings. (Orth) 29 Korshak, Stephen D. (Ed). A Hannes Bok Showcase. (Albert) 34 McCarthy, Helen. AniIoo J : A Beginner's Guide to Japanese Animation. (Klossner) 35 SFRA Re\liew#218. July/August 1995 Scheick, william J. (Ed). The Critical Resp:Jnse to H.G •. ~lls. (Huntington) 36 Schlobin, Roger C. and Irene R. Harrison. Andre Norton: A primaIy and Secondary Bibliography (Bogstad) 38 silver, Alain and Janes Ursini.