Read a Complete Transcript of the Interview

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Music 80C History and Literature of Electronic Music Tuesday/Thursday, 1-4PM Music Center 131

Music 80C History and Literature of Electronic Music Tuesday/Thursday, 1-4PM Music Center 131 Instructor: Madison Heying Email: [email protected] Office Hours: By Appointment Course Description: This course is a survey of the history and literature of electronic music. In each class we will learn about a music-making technique, composer, aesthetic movement, and the associated repertoire. Tests and Quizzes: There will be one test for this course. Students will be tested on the required listening and materials covered in lectures. To be prepared students must spend time outside class listening to required listening, and should keep track of the content of the lectures to study. Assignments and Participation: A portion of each class will be spent learning the techniques of electronic and computer music-making. Your attendance and participation in this portion of the class is imperative, since you will not necessarily be tested on the material that you learn. However, participation in the assignments and workshops will help you on the test and will provide you with some of the skills and context for your final projects. Assignment 1: Listening Assignment (Due June 30th) Assignment 2: Field Recording (Due July 12th) Final Project: The final project is the most important aspect of this course. The following descriptions are intentionally open-ended so that you can pursue a project that is of interest to you; however, it is imperative that your project must be connected to the materials discussed in class. You must do a 10-20 minute in class presentation of your project. You must meet with me at least once to discuss your paper and submit a ½ page proposal for your project. -

Robert Ashley the Old Man Lives in Concrete

Joan La Barbara – composer / performer / sound artist – explores the human voice as a multi-faceted instrument, expanding traditional boundaries in composition, using a unique vocabulary of experimental and extended vocal techniques – multiphonics, circular singing, ululation and glottal clicks – that have become her “signature sounds.” Awards include a 2008 American Music Center Letter of Distinction, a Guggenheim Fellowship in Music Composition, DAAD Artist-in- Residency in Berlin, seven NEA grants and numerous commissions for concert, theater and radio works. La Barbara has created sound scores for film, video and dance and produced twelve recordings of her own works, including Voice Is the Original Instrument, a double CD of her historical compositions for Lovely Music. 73 Poems, her collaboration with text-artist Kenneth Goldsmith, was included in “The American ROBERT ASHLEY Century Part II: SoundWorks” at the Whitney Museum of American Art. Messa di Voce, an interactive media performance work created in THE OLD MAN LIVES IN CONCRETE collaboration with Jaap Blonk, Golan Levin and Zachary Lieberman, premiered to acclaim at Ars Electronica 2003. La Barbara teaches Music and libretto composition at NYU and is working on a new opera. ROBERT ASHLEY Singers David Moodey has designed for and toured with Molissa Fenley and Dancers since 1986. His design for Fenley’s State of Darkness earned SAM ASHLEY, THOMAS BUCKNER, JACQUELINE HUMBERT, him a Bessie award for lighting design. He has also designed and JOAN LA BARBARA AND ROBERT ASHLEY toured numerous shows for Paul Lazar and Annie-B Parsons and their Electronic orchestra composed by company, Big Dance Theater, and for David Neumann’s feedforward at DTW. -

PROGRAM NOTES the Expanded Sonic Potential of the Voice

ABOUT THE ARTISTS Joan La Barbara La Barbara is a composer, performer, sound artist and actor renowned for developing a unique vocabulary of experimental and extended vocal techniques (multiphonics, circular singing, ululation and glottal clicks; her “signature sounds”), influencing generations of other composers and singers. Awards, prizes and fellowships include The Foundation for Contemporary Arts John Cage Award (2016); Premio Internazionale Demetrio Stratos; DAAD-Berlin and Civitella Ranieri Artist-in-Residencies; Guggenheim Fellowship in Music Composition; seven National Endowment for the Arts awards (Music Composition, Opera/Music Theater, Inter-Arts, Recording, Solo Recital, Visual Arts), and numerous commissions for multiple voices, chamber ensembles, theatre, orchestra, interactive technology, and soundscores for dance, video and film. Her multi-layered textural compositions were presented at Brisbane Biennial, Festival d’Automne à Paris, Warsaw Autumn, MaerzMusik Berlin and Lincoln Center, among other international venues. She has collaborated with visual artists Matthew Barney, Judy Chicago, Ed Emshwiller, Kenneth Goldsmith, Bruce Nauman, Steina, Woody Vasulka and Lawrence Weiner, and has premiered landmark compositions composed for her, including Morton Feldman’s Three Voices; Morton Subotnick’s chamber opera Jacob’s Room and his Hungers and Intimate Immensity; the title role in Robert Ashley’s opera Now Eleanor’s Idea and his Dust; Philip Glass and Robert Wilson’s Einstein on the Beach; Steve Reich’s Drumming; and John Cage’s Eight Whiskus and Solo for Voice 45 from Song Books. Recordings of her works include ShamanSong (New World), Sound Ellen Rietbrock Paintings and her seminal works from Voice is the Original Instrument (1970, Lovely Music). In addition to her internationally acclaimed discs of Feldman and Cage, she has recorded for A&M Horizon, Centaur, Deutsche Grammophon, Nonesuch, Mode, Music & Arts, MusicMasters, Musical Heritage, Newport Classic, Sony, Virgin, Voyager and Wergo. -

Underwater Music: Tuning Composition to the Sounds of Science

Underwater Music: Tuning Composition to the Sounds of Science The MIT Faculty has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters. Citation Helmreich, Stefan. “Underwater Music: Tuning Composition to the Sounds of Science.” Oxford Handbooks Online (December 2, 2011). As Published http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195388947.013.0044 Publisher Oxford University Press Version Original manuscript Citable link http://hdl.handle.net/1721.1/114601 Terms of Use Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike Detailed Terms http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/ OUP UNCORRECTED FIRST-PROOF 7/6/11 CENVEO chapter 6 UNDERWATER MUSIC: TUNING COMPOSITION TO THE SOUNDS OF SCIENCE stefan helmreich Introduction How should we apprehend sounds subaqueous and submarine? As humans, our access to underwater sonic realms is modulated by means fl eshy and technological. Bones, endolymph fl uid, cilia, hydrophones, and sonar equipment are just a few apparatuses that bring watery sounds into human audio worlds. As this list sug- gests, the media through which humans hear sound under water can reach from the scale of the singular biological body up through the socially distributed and techno- logically tuned-in community. For the social scale, which is peopled by submari- ners, physical oceanographers, marine biologists, and others, the underwater world —and the undersea world in particular — often emerge as a “fi eld” (a wildish, distributed space for investigation) and occasionally as a “lab” (a contained place for controlled experiments). In this chapter I investigate the ways the underwater realm manifests as such a scientifi cally, technologically, and epistemologically apprehensible zone. -

Downloads/9215D25f931f4d419461a88825f3f33f20160622021223/Cb7be6

JOAN LA BARBARA’S EARLY EXPLORATIONS OF THE VOICE by Samara Ripley B.Mus., Mount Allison University, 2014 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in The Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies (Music) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) August 2016 © Samara Ripley, 2016 Abstract Experimental composer and performer Joan La Barbara treats the voice as a musical instrument. Through improvisation, she has developed an array of signature sounds, or extended vocal techniques, that extend the voice beyond traditional conceptions of Western classical singing. At times, her signature sounds are primal and unfamiliar, drawing upon extreme vocal registers and multiple simultaneous pitches. In 2003, La Barbara released Voice is the Original Instrument, a two-part album that comprises a selection of her earliest works from 1974 – 1980. The compositions on this album reveal La Barbara’s experimental approach to using the voice. Voice Piece: One-Note Internal Resonance Investigation explores the timbral palette within a single pitch. Circular Song plays with the necessity of a singer’s breath by vocalizing, and therefore removing, all audible inhalations and exhalations. Hear What I Feel brings the sense of touch into an improvisatory composition and performance experience. In October Music: Star Showers and Extraterrestrials, La Barbara moves past experimentation and layers her different sounds into a cohesive piece of music. This thesis is a study of La Barbara’s treatment of the voice in these four early works. I will frame my discussion with theories of the acousmatic by Mladen Dolar and Brian Kane and will also draw comparisons with Helmut Lachnemann’s musique concrète instrumentale works. -

Worldnewmusic Magazine

WORLDNEWMUSIC MAGAZINE ISCM During a Year of Pandemic Contents Editor’s Note………………………………………………………………………………5 An ISCM Timeline for 2020 (with a note from ISCM President Glenda Keam)……………………………..……….…6 Anna Veismane: Music life in Latvia 2020 March – December………………………………………….…10 Álvaro Gallegos: Pandemic-Pandemonium – New music in Chile during a perfect storm……………….....14 Anni Heino: Tucked away, locked away – Australia under Covid-19……………..……………….….18 Frank J. Oteri: Music During Quarantine in the United States….………………….………………….…22 Javier Hagen: The corona crisis from the perspective of a freelance musician in Switzerland………....29 In Memoriam (2019-2020)……………………………………….……………………....34 Paco Yáñez: Rethinking Composing in the Time of Coronavirus……………………………………..42 Hong Kong Contemporary Music Festival 2020: Asian Delights………………………..45 Glenda Keam: John Davis Leaves the Australian Music Centre after 32 years………………………….52 Irina Hasnaş: Introducing the ISCM Virtual Collaborative Series …………..………………………….54 World New Music Magazine, edition 2020 Vol. No. 30 “ISCM During a Year of Pandemic” Publisher: International Society for Contemporary Music Internationale Gesellschaft für Neue Musik / Société internationale pour la musique contemporaine / 国际现代音乐协会 / Sociedad Internacional de Música Contemporánea / الجمعية الدولية للموسيقى المعاصرة / Международное общество современной музыки Mailing address: Stiftgasse 29 1070 Wien Austria Email: [email protected] www.iscm.org ISCM Executive Committee: Glenda Keam, President Frank J Oteri, Vice-President Ol’ga Smetanová, -

Miller Theatre Presents a Composer Portrait of ANNEA LOCKWOOD, 11/14 10/16/19, 2�45 PM

Miller Theatre presents a Composer Portrait of ANNEA LOCKWOOD, 11/14 10/16/19, 245 PM VIEW THIS EMAIL IN YOUR BROWSER FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE PRESS CONTACTS October 15, 2019 Aleba Gartner, 212/206-1450 Tickets & Information: 212/854-7799 [email protected] millertheatre.com Lauren Bailey Cognetti, 212/854-1633 [email protected] "Miller’s utterly indispensable Composer Portraits series reaches its 20th season this year, two decades in which these concerts have made or cemented the reputations of dozens of composers.“ — The New York Times 9/20/19 Miller Theatre at Columbia University School of the Arts continues its 20th season of Composer Portraits with Annea Lockwood featuring Estelí Gomez, voice Nate Wooley, trumpet Yarn/Wire https://mailchi.mp/alebaco/miller-theatre-presents-annea-lockwood-portrait?e=076444d635 Page 1 of 10 Miller Theatre presents a Composer Portrait of ANNEA LOCKWOOD, 11/14 10/16/19, 245 PM Program includes a world premiere co-commissioned by New York State Council on the Arts and Miller Theatre Thursday, November 14, 2019, 8:00 P.M. Miller Theatre (2960 Broadway at 116th Street) Tickets: starting at $20; Students with valid ID: starting at $7 https://mailchi.mp/alebaco/miller-theatre-presents-annea-lockwood-portrait?e=076444d635 Page 2 of 10 Miller Theatre presents a Composer Portrait of ANNEA LOCKWOOD, 11/14 10/16/19, 245 PM Photo by Kyle Dorosz for Miller Theatre. From Miller Theatre Executive Director Melissa Smey: “One of my programming goals for Composer Portraits is to show the breadth of creative practice used by composers today. -

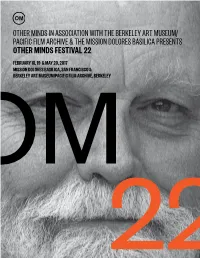

Other Minds in Association with the Berkeley Art

OTHER MINDS IN ASSOCIATION WITH THE BERKELEY ART MUSEUM/ PACIFIC FILM ARCHIVE & THE MISSION DOLORES BASILICA PRESENTS OTHER MINDS FESTIVAL 22 FEBRUARY 18, 19 & MAY 20, 2017 MISSION DOLORES BASILICA, SAN FRANCISCO & BERKELEY ART MUSEUM/PACIFIC FILM ARCHIVE, BERKELEY 2 O WELCOME FESTIVAL TO OTHER MINDS 22 OF NEW MUSIC The 22nd Other Minds Festival is present- 4 Message from the Artistic Director ed by Other Minds in association with the 8 Lou Harrison Berkeley Art Museum/Pacific Film Archive & the Mission Dolores Basilica 9 In the Composer’s Words 10 Isang Yun 11 Isang Yun on Composition 12 Concert 1 15 Featured Artists 23 Film Presentation 24 Concert 2 29 Featured Artists 35 Timeline of the Life of Lou Harrison 38 Other Minds Staff Bios 41 About the Festival 42 Festival Supporters: A Gathering of Other Minds 46 About Other Minds This booklet © 2017 Other Minds, All rights reserved 3 MESSAGE FROM THE EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR WELCOME TO A SPECIAL EDITION OF THE OTHER MINDS FESTIVAL— A TRIBUTE TO ONE OF THE MOST GIFTED AND INSPIRING FIGURES IN THE HISTORY OF AMERICAN CLASSICAL MUSIC, LOU HARRISON. This is Harrison’s centennial year—he was born May 14, 1917—and in addition to our own concerts of his music, we have launched a website detailing all the other Harrison fêtes scheduled in his hon- or. We’re pleased to say that there will be many opportunities to hear his music live this year, and you can find them all at otherminds.org/lou100/. Visit there also to find our curated compendium of Internet links to his work online, photographs, videos, films and recordings. -

![Leonardo Music Journal [1])](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7187/leonardo-music-journal-1-1967187.webp)

Leonardo Music Journal [1])

IntroductIon LMJ 23: Sound Art What’s in a name? That which we call “Music” is judged by the full weight of history and fashion; substitute “Sound Art” and most of these preconceptions fall away. As recently as a decade ago the reaction instead might have been bemusement. The term Sound Art was coined in the late 1960s to describe sonic activities taking place outside the concert hall: interactive installations, listening walks, environmental recordings, open duration sound events—even “happenings” and performance art were occasionally lumped under this rubric. For many years Sound Art remained an interstitial activity, falling between music and visual art, embraced fully by neither. Many composers viewed self-styled Sound Artists as failed mem- bers of their own club pursuing “a career move . a branding exercise” (as Chris Mann is quoted as saying in Ricardo Arias’s contribution to this volume of Leonardo Music Journal [1]). Most museums and galleries, in turn, shied away from an art form that was often stunningly unvisual even by the standards of Conceptual Art and for which there appeared to be no mar- ket. (Gallery assistants often found it very irritating to boot.) By 2013, however, Sound Art clearly has been accepted as an identifiable musical genre, an art world commodity, and a subject of critical study. Its newfound visibility can be traced to a number of aesthetic, technological and economic factors. First and foremost, I suspect, is the ubiquity of video in contemporary life: On the heels of the ever-declining price of camcord- ers, cellphone cameras have brought the world—from out-of-tune Van Halen concerts to the Arab Spring—to our laptops, and every video clip is invariably accompanied by sound. -

Annea Lockwood, a New Zealand–Born Composer Who Settled in The

Annea Lockwood, a New Zealand–born composer who settled in the United States in 1973, distinguishes herself with works ingeniously combining recorded found and processed sounds, live-performance and visual components, and exhibiting her acute sense of timbre. Lockwood first explored electro-acoustic music and mixed media in the mid-1960s in Europe. Initially tutored by Peter Racine Fricker and Gottfried Michael Koenig, she gained inspiration from such experimental American composers as John Cage, Morton Feldman, Pauline Oliveros, and Ruth Anderson. While perhaps best known for her 1960s “glass concerts” featuring manifold glass-based sounds and her notorious Piano Transplants—burning, burying, and drowning obsolete pianos—she was drawn to the complex beauty of sounds found in the natural environment, which she captured on tape. Lockwood was especially fascinated with the sonorities of moving water and water’s calming and healing properties and thus started an archive of recorded river sounds. This project led to various sound installations and, most important, to her now legendary and large-scale A Sound Map of the Hudson River (1982) and A Sound Map of the Danube (2005), soundscapes tracing these rivers from their sources to their deltas.1 Lockwood also incorporated recorded sounds of mating tigers, purring cats, tree frogs, volcanoes, earthquakes, and fire in such works as Tiger Balm (1970) and World Rhythms (1975). From the 1970s, she explored improvisation and alternative performance techniques and asked her performers to use natural sound sources and instruments including rocks, stones, and conch shells in Rokke (with Eva Karczag, 1987), Nautilus (1989), A Thousand Year Dreaming (1990), Ear-Walking Woman (1996), and Jitterbug (2007), among other compositions. -

Love of Life Orchestra Ceciltaylor

BAm BROOKLYN ACADEMY OF MUSIC LOVE OF LIFE ORCHESTRA CECIL TAYLOR / .WORLD SAXOPHONE OUARTET . ~ =~=~':i-=-. -- .~ ~ ~ @ FE S T I V A L • 8 5 'BROOKLYN ACADEMY OF MUSIC !!!!!!!!!!!!!!!! Harvey Lichtenstein, President and ChiefExecutive Officer !!!!!!!!!!!!!!! CAREY PLAYHOUSE November 29,19858:00 pm November 30, 1985 8:00 pm PETER GORDON'S LOVE OF LIFE ORCHESTRA Musical Direction: PETER GORDON AND DAVID VAN TIEGHEM Musicians: Peter Gordon Richard Landry "Blue" Gene Tyranl}Y . David Van Tieghem Lenny Pickett Linda Hudes RikAlbani Ned Sublette Tony Garnier Peter Zummo Randy Gun Rebecca Armstrong Larry Saltzman A concert of new music composed by: Peter Gordon David Van Tieghem Linda Hudes Randy Gun "Blue" Gene Tyranny Ned Sublette Sound mix: Eric'Liljestrand Lighting: Jan Kroeze NEXT WAVE FESTJVAL 1985 The NEXT WAVE Production and Touring Fund is supported by the National Endowment for the Arts, the National Endowment for the Humanities, the Rockefeller Foundation, the Ford Foundation, the Pew Memorial Trust, Remy Martin Amerique, AT&T, the William and Flora Hewlett Founda tion, WiIIiWear Ltd., Goethe House New York, the New York Council for the Humanities, the Educational Foundation of America, the Howard Gilman Foundation, the BestProducts Foundation, Mee~ the Composer, Inc., Abraham & Straus/Federated Department Stores Foundation, Inc., the CIGNA Corporation, Mary Boone,Gallery, and the BAM NEXT w.fVE Producers Council. Additional funds for the NEXT w.fVE FESJ'IVAL are proyided by ~.~.ew York State Council on the Ans~ the Mary Aagler Cary Charitable Trust, Philip Morris Incorporated, the New York Community Trust, ManufaCtu¥s Hanover, Lila Acheson Wallace, the National Institute for Music Theater, the William and Mary Greve Foundation, Inc., the Samuel I. -

A Festival of Unexpected New Music February 28March 1St, 2014 Sfjazz Center

SFJAZZ CENTER SFJAZZ MINDS OTHER OTHER 19 MARCH 1ST, 2014 1ST, MARCH A FESTIVAL FEBRUARY 28 FEBRUARY OF UNEXPECTED NEW MUSIC Find Left of the Dial in print or online at sfbg.com WELCOME A FESTIVAL OF UNEXPECTED TO OTHER MINDS 19 NEW MUSIC The 19th Other Minds Festival is 2 Message from the Executive & Artistic Director presented by Other Minds in association 4 Exhibition & Silent Auction with the Djerassi Resident Artists Program and SFJazz Center 11 Opening Night Gala 13 Concert 1 All festival concerts take place in Robert N. Miner Auditorium in the new SFJAZZ Center. 14 Concert 1 Program Notes Congratulations to Randall Kline and SFJAZZ 17 Concert 2 on the successful launch of their new home 19 Concert 2 Program Notes venue. This year, for the fi rst time, the Other Minds Festival focuses exclusively on compos- 20 Other Minds 18 Performers ers from Northern California. 26 Other Minds 18 Composers 35 About Other Minds 36 Festival Supporters 40 About The Festival This booklet © 2014 Other Minds. All rights reserved. Thanks to Adah Bakalinsky for underwriting the printing of our OM 19 program booklet. MESSAGE FROM THE ARTISTIC DIRECTOR WELCOME TO OTHER MINDS 19 Ever since the dawn of “modern music” in the U.S., the San Francisco Bay Area has been a leading force in exploring new territory. In 1914 it was Henry Cowell leading the way with his tone clusters and strumming directly on the strings of the concert grand, then his students Lou Harrison and John Cage in the 30s with their percussion revolution, and the protégés of Robert Erickson in the Fifties with their focus on graphic scores and improvisation, and the SF Tape Music Center’s live electronic pioneers Subotnick, Oliveros, Sender, and others in the Sixties, alongside Terry Riley, Steve Reich and La Monte Young and their new minimalism.