Lethal Power How Burning Coal Is Killing People in Australia Dr

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

State Electricity Commission of Victoria Fifty-Seventh Annual Report

1976 VICTORIA STATE ELECTRICITY COMMISSION OF VICTORIA FIFTY-SEVENTH ANNUAL REPORT FOR THE FINANCIAL YEAR ENDED 30TH JUNE, 1976 TOGETHER WITH APPENDICES PRESENTED TO PARLIAMENT PURSUANT TO SECTION 82 (b) OF STATE ELECTRICITY COMMISSION ACT No. 6377. By Authon/y: C. H. RlXON, GOVERNMENT PRINTER, ~lELBOURNE. No. 44.-1l818f76.-PRICE $1·20 ,~ ~~~~ SEC STATE ELECTRICITY COMMISSION OF VICTORIA FIFTY SEVENTH REPORT 1975-1976 CONTENTS Page Page The State Electricity Commission of Victoria 5 Brown Coal Development 18 Statement of Commission Objectives 5 Brown Coal Production 18 Summary of Activities 6 Morwell Open Cut 18 Annual Report 7 Yallourn Open Cut 18 Business Result~ 9 Lay Yang Open Cut 18 Major Capital Works 14 Review of Major Activities 19 Newport Power Station 14 Marketing and Distribution 19 Development Program 15 Yallourn Township 22 Yallourn W Power Station 15 New Legislation 22 - Lay Yang Project 15 Scientific Research 22 Dartmouth Hydro-electric Project 15 Publi c Safety and Other Regulatory Responsibilities 22 Transmission & Distribution System 16 Commissioners 23 Electricity Production 17 Personnel and Organisa tion 23 North The Loy Yang project will be the Commission·s largest development yet undertaken. Legislation to authorise the project is now before Parliament. In its Progress Report . the Parliamentary Public Works Committee which conducted a public enquiry has recommended that the Government authorise the Commission to proceed with plann ing. The project will involve the development of an open cut on the Loy Yang Brown Coal field and the construction of a 4000 MW power generating station adjacent to and south of the open cut. together with ancillary works. -

Victorian Transfer Limit Advice – Multiple Outages 3

November 2018 For the National Electricity Market PURPOSE AEMO has prepared this document to provide information about voltage and transient stability limits for flows to and from Victoria, as at the date of publication. DISCLAIMER This document or the information in it may be subsequently updated or amended. This document does not constitute legal or business advice, and should not be relied on as a substitute for obtaining detailed advice about the National Electricity Law, the National Electricity Rules, or any other applicable laws, procedures or policies. AEMO has made every effort to ensure the quality of the information in this document but cannot guarantee its accuracy or completeness. Accordingly, to the maximum extent permitted by law, AEMO and its officers, employees and consultants involved in the preparation of this document: • make no representation or warranty, express or implied, as to the currency, accuracy, reliability or completeness of the information in this document; and • are not liable (whether by reason of negligence or otherwise) for any statements or representations in this document, or any omissions from it, or for any use or reliance on the information in it. © 2018 Australian Energy Market Operator Limited. The material in this publication may be used in accordance with the copyright permissions on AEMO’s website. VERSION CONTROL Version Release date Changes 3 23/11/2018 New Template Applied 2 23/07/2018 Updated voltage stability import limits 1 01/08/2017 Initial version © AEMO 2018 | Victorian Transfer Limit Advice – Multiple Outages 3 1. Introduction 7 1.1 Other AEMO publications 7 1.2 Calculating transient and voltage stability limits 7 1.3 Methodology 7 1.4 Conversion to constraint equations 8 2. -

Newport Power Station Cattle Grazing at the Metropolitan Sewage

PUBLIC UTILITIES Newport Power Station Cattle grazing at the Metropolitan Sewage Far m A catchment area for Melbourne's water supply 118 E1ECTR1C1T> whole system will ha\e to be undertaken in the near future. stations in the north-eastern part of the State, and two The Board has considered various proposals for amplifi regional diesel-electric stations at Shepparton and Warr cation and has approved of detailed investigations, which nambool. are now being carried out, for a scheme which provides for Operating exclusively on brown coal of high moisture a new outfall sower to discharge into Bass Strait near Cape content from the Yallourn open cut in the Latrobe Valley, Schanck and which will divert from the Werribee system the steam-electric power station at Yallourn is the most the sewage from the eastern suburbs. The construction of important station in the inter-connected system. Electricity ihis sewer will enable sewerage facilities to be extended to generated there in 1951-52 was approximately 46% of the those southern portions of the metropolitan area for which total amount generated. This power station is designed to no provision has yet been made. carry the sustained base load, while the purpose of the met When these amplification proposals are completed, there ropolitan and regional stations is mainly to generate the will be no physical ditficulty in extending sewerage facilities additional power needed during peak loading periods. Apart to an expanded urban area including the southern suburbs from local supplies in the Gippsland area, the power of Chelsea, Frankston, and portions of Dandenong. -

Yallourn Fact Sheet

Yallourn fact sheet The EnergyAustralia Yallourn power station and mine operate on the lands of the Braiakaulung people of the Gunaikurnai nation and we acknowledge them as Traditional Owners, as well as acknowledge their living culture and ~2M Powering strong connections to their Country. around 2 million Australian homes A century of support Powering Victoria For more than a century Victoria’s Latrobe • Yallourn operates 24 hours a day, 365 days a Valley has generated electricity to illuminate, year, with a generating capacity up to warm, cool and power millions of homes and 1480 MW ~20% businesses across the state and the country. Of Victoria’s • Yallourn provides about 20 per cent of electricity is Yallourn has been part of the region’s proud Victoria’s electricity, and about eight per cent powered by heritage since 1921, when the former State of Australia’s National Electricity Market (NEM) Yallourn Electricity Commission of Victoria built a power • Yallourn provides power to around two station fuelled by brown coal. million homes. That temporary pioneering project was a success and a permanent power station was Highly-skilled workforce ~8% built on the banks of the Latrobe River in 1924. • Yallourn employs around 500 permanent Of the NEM is workers on site powered by This was followed by the construction of other Yallourn power stations on the site through to the 1974 • For three to four months of some years, construction and operation of the power station our workforce increases to 1000 when we we know today. undertake major unit outages, along with four yearly integrity maintenance works adding an 500+ extra 150-200 workers Permanent • Each Yallourn worker is estimated to workers and up to 1000 during generate an additional four to five jobs in the maintenance Latrobe Valley • At any given time, Yallourn has at least 15 apprentices on site. -

Distribution Annual Planning Report 2021 – 2025

Distribution Annual Planning Report 2021 – 2025 Issue number 8 Status Approved Approver Tom Langstaff Date of approval 21 December 2020 AusNet Services Distribution Annual Planning Report 2021 - 2025 ISSUE/AMENDMENT STATUS Issue Date Description Author Approved by Number 1 20/12/2013 2014-2018 Issue (First Issue) M Wickramasuriya D Postlethwaite S Lees M Cavanagh 2 19/12/2014 2015-2019 Issue S Lees J Bridge M Cavanagh 3 24/12/2015 2016-2020 Issue M Wickramasuriya J Bridge S Lees M Cavanagh 4 23/12/2016 2017-2021 Issue M Wickramasuriya J Bridge S Sao M Cavanagh 5 22/12/2017 2018-2022 Issue M Wickramasuriya J Bridge T Langstaff 6 27/12/2018 2019-2023 Issue M Wickramasuriya T Langstaff J Pollock 6.1 30/04/2019 Revision to 2019-2023 Issue to include M Wickramasuriya T Langstaff geographic areas subject to a REFCL J Pollock condition, as per Electricity Distribution S Sao Code V.9A (amended August 2018). 7 20/12/2019 2020-2024 Issue J Pollock T Langstaff A Erceg S Sao 7.1 13/01/2020 Updated RIT timeframes (Section 8.2) and J Pollock T Langstaff other minor amendments including broken A Erceg links S Sao 8 18/12/2020 2021-2025 Issue J Pollock T Langstaff S Sao D Johnstone Disclaimer This document belongs to AusNet Services and may or may not contain all available information on the subject matter this document purports to address. The information contained in this document is subject to review and AusNet Services may amend this document at any time. -

Yallourn Coal Field Re-Alignment Project Environment Report

Yallourn Coal Field Re-alignment Project Environment Report Assessment Minister for Planning June 2010 Glossary AHD Australian Height Datum CHMP Cultural Heritage Management Plan, prepared under Aboriginal Heritage Act 2006 dBL Decibels DEWHA Commonwealth Department of the Environment, Water, Heritage and the Arts DPCD Victorian Department of Planning and Community Development DPI Victorian Department of Primary Industries DSE Victorian Department of Sustainability and Environment EES Environment Effects Statement EMP Environmental Management Plan EPA Victorian Environment Protection Authority EP Act Environment Protection Act 1970 EPBC Act Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 ERC Environmental Review Committee ESD ecologically sustainable development EVC Ecological Vegetation Class FFG Act Flora and Fauna Guarantee Act 1988 (Vic.) GHG Greenhouse Gases GL gigalitres ha hectares hha habitat hectares km kilometres LPPF Local Planning Policy Framework m, m3 metres, cubic metres MEA maximum extent achievable MRSD Act Mineral Resources (Sustainable Development) Act 1990 Mt Mega tonnes (million tonnes) NVMF Victoria’s Native Vegetation Management Framework P&E Act Planning and Environment Act 1987 PM10 particles or “particulate matter” with equivalent aerodynamic diameter of 10 micrometers or less SEPPs State Environment Protection Policies SPPF State Planning Policy Framework i Table of Contents 1 Introduction................................................................................................................ -

Stakeholder Submissions Consolidated

Stakeholder submissions consolidated We received 19 submissions on our draft decision ‘Building trust through new customer entitlements in the retail energy market’ which was released on 7 September 2018. Feedback was provided by 13 retailers (including one confidential submission), 5 consumer groups and the Energy and Water Ombudsman (Victoria). The parties who made non-confidential submissions can be found on the pages below: Submission provided by: Page number AGL 3 Alinta Energy 22 Australian Energy Council 28 Community Information & Support Victoria 36 (CISVic) Consumer Action Law Centre 39 Consumer Policy Research Centre 50 Energy and Water Ombudsman (Victoria) 54 EnergyAustralia 60 ERM Power 68 Momentum Energy 71 Onsite Energy Solutions 79 Origin Energy 85 1 Essential Services Commission Stakeholder submissions on draft decision 1 Powershop 96 Red Energy and Lumo Energy 104 Renew (Alternative Technology Association) 107 Simply Energy 114 Sumo Power 117 Victorian Council of Social Service 121 2 Essential Services Commission Stakeholder submissions on draft decision 1 AGL Enercv Limited ABN: 74 115 061375 t: 02 9921 2999 f: 02 9921 2552 agl agl.com.au Essential Services Commission Submitted electronically: [email protected] 5 October 2018 Essential services Commission - Building trust through new customer entitlements in the retail energy market AGL Energy (AGL) welcomes the opportunity to make a submission in response to the Essential Services Commission Victoria (Commission) draft decision on implementing recommendations 3F, 3G, 3H of the Independent Review of Electricity and Gas Retail Markets (Thwaites review). We recognise the complexities in developing a regulatory response to the Thwaites recommendations and appreciate the tight timeframes the Commission has had to work in. -

中電控股有限公司 CLP Holdings Limited Announcement

Page 1 of 4 Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing Limited and The Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited take no responsibility for the contents of this announcement, make no representation as to its accuracy or completeness and expressly disclaim any liability whatsoever for any loss howsoever arising from or in reliance upon the whole or any part of the contents of this announcement. 中電控股有限公司 CLP Holdings Limited (incorporated in Hong Kong with limited liability) (Stock Code: 00002) Announcement EnergyAustralia and the Victorian Government collaborate on accelerating the energy transition – Agreement on the advanced retirement of Yallourn Power Station to 2028 Highlights: • CLP Holdings’ EnergyAustralia and Australia’s Victoria State Government have agreed on the advanced retirement of Yallourn Power Station. • EnergyAustralia will build a new commercial utility-scale battery capacity of 350MW* by 2026 with the support of the Victorian Government. • EnergyAustralia’s current direct carbon emissions will reduce by approximately 60 per cent when Yallourn retires in 2028. On 9 March 2021, EnergyAustralia Holdings Limited (“EnergyAustralia”), a wholly-owned subsidiary of CLP Holdings Limited (“CLP Holdings” or the “Company”), entered into an agreement (the “Agreement”) with the State Government of Victoria, Australia (the “Victorian Government”) on the advanced retirement of Yallourn coal-fired power station located in the Latrobe Valley, Victoria (“Yallourn”). Page 2 of 4 The Agreement The Agreement encompasses the following: 1) the orderly retirement of Yallourn in 2028, four years prior to the end of its technical life; 2) EnergyAustralia to deliver by 2026 a new utility-scale battery capacity of 350MW* in Victoria; and 3) EnergyAustralia will provide a comprehensive workforce transition package. -

1 June 2017 Cimic's Thiess Awarded $195 Million

1 JUNE 2017 CIMIC’S THIESS AWARDED $195 MILLION YALLOURN MINING EXTENSION CIMIC Group’s mining services provider Thiess, as part of the Roche Thiess Linfox (RTL) joint venture, has been awarded a contract to continue mining operations at the Yallourn mine, located in Victoria’s Latrobe Valley. The alliance agreement with Energy Australia will extend RTL’s existing operations at the mine to 2026. The contract will generate revenue of approximately $450 million for RTL, of which Thiess’ share is $195 million. CIMIC Chief Executive Officer Adolfo Valderas said: “This extension is a testament to the strength of the relationship between Energy Australia, Thiess and RTL, reflecting the goodwill that has been developed during the past 16 years.” CIMIC Group Executive Mining and Mineral Processing, and Thiess Manager Director, Michael Wright said: “This contract extension provides certainty to the committed workforce who have contributed to the Alliance’s success at the site, through the delivery of innovative solutions. “RTL and Energy Australia have provided mining services at Yallourn since commencing operations in 2000, with RTL introducing a new and innovative coal mining technique using highly modified CAT D11R carry dozers pushing to feeder breakers.” The new contract continues to deliver the mining of overburden and coal, and includes the maintenance of an extensive network of conveyors and other infrastructure. Yallourn open cut coal mine supplies the Yallourn Power Station in the Latrobe Valley, providing 20 per cent of Victoria’s electricity requirements. ENDS Issued by CIMIC Group Limited ABN 57 004 482 982 www.cimic.com.au Further information Ms Marta Olba, Group Manager Investor Relations T+61 2 9925 6134 Ms Fiona Tyndall, General Manager Communications T+61 2 9925 6188 CIMIC Group Limited (ASX: CIM) is one of the world’s leading international contractors and the world’s largest contract miner. -

Fossil Fails in the Smart State

Fossil fails in the Smart State Gas and coal power plant breakdowns in Victoria Victorian brown coal-fired power plants are some of the worst performing stations in the National Electricity Market. With hot and dry conditions forecast for the rest of this summer, Victoria is at risk of further breakdowns of aging coal generators, insufficient supply and blackouts. Discussion paper Audrey Quicke Bill Browne February 2020 ABOUT THE AUSTRALIA INSTITUTE The Australia Institute is an independent public policy think tank based in Canberra. It is funded by donations from philanthropic trusts and individuals and commissioned research. We barrack for ideas, not political parties or candidates. Since its launch in 1994, the Institute has carried out highly influential research on a broad range of economic, social and environmental issues. OUR PHILOSOPHY As we begin the 21st century, new dilemmas confront our society and our planet. Unprecedented levels of consumption co-exist with extreme poverty. Through new technology we are more connected than we have ever been, yet civic engagement is declining. Environmental neglect continues despite heightened ecological awareness. A better balance is urgently needed. The Australia Institute’s directors, staff and supporters represent a broad range of views and priorities. What unites us is a belief that through a combination of research and creativity we can promote new solutions and ways of thinking. OUR PURPOSE – ‘RESEARCH THAT MATTERS’ The Institute publishes research that contributes to a more just, sustainable and peaceful society. Our goal is to gather, interpret and communicate evidence in order to both diagnose the problems we face and propose new solutions to tackle them. -

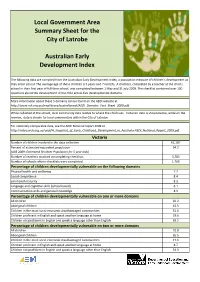

Local Government Area Summary Sheet for the City of Latrobe

Local Government Area Summary Sheet for the City of Latrobe Australian Early Development Index The following data are compiled from the Australian Early Development Index, a population measure of children’s development as they enter school. The average age of these children is 5 years and 7 months. A checklist, completed by a teacher at the child’s school in their first year of full-time school, was completed between 1 May and 31 July 2009. The checklist contained over 100 questions about the development of the child across five developmental domains. More information about these 5 domains can be found on the AEDI website at http://www.rch.org.au/emplibrary/australianedi/AEDI_Domains_Fact_Sheet_2009.pdf While collected at the school, local community data relates to where the child lives. Victorian data is shown below, while on the reverse, data is shown for local communities within the City of Latrobe. For nationally comparable data, see the AEDI National report 2009 at http://video.wch.org.au/aedi/A_Snapshot_of_Early_Childhood_Development_in_Australia-AEDI_National_Report_2009.pdf Victoria Number of children involved in the data collection 61,187 Percent of estimated equivalent population 94.2 (ABS 2009: Estimated Resident Population for 5 year olds) Number of teachers involved in completing checklists 3,783 Number of schools where checklists were completed 1,765 Percentage of children developmentally vulnerable on the following domains Physical health and wellbeing 7.7 Social competence 8.4 Emotional maturity 8.3 Language and cognitive -

Yallourn Mine Batter Failure Inquiry – 30 June 2008

Mining Warden Yallourn Mine Batter Failure Inquiry __________________________________ Ordered to be printed __________________________________ VICTORIAN GOVERNMENT PRINTER No 156 Session 2006–08 Mining Warden - Yallourn Mine Batter Failure Inquiry EXECUTIVE SUMMARY I was appointed a Mining Warden in the State of Victoria and requested to undertake an Inquiry into the Yallourn Mine Batter Failure. The Terms of Reference for the inquiry were to: a) Establish the facts, circumstances and causes surrounding the collapse, b) Examine any mine safety issues and c) Make high level recommendations to prevent or minimise the risk of similar future events. This executive summary is presented as a brief summary of the findings of the Inquiry. The main body of the report includes detailed discussion on all elements. The executive summary should not be taken out of context or read in isolation from the main report. The failure occurred between 1:30am and 2:10am on 14th November 2007. The failure is located on the northeast batter (NE Batter) of the Yallourn East Field Mine (YEF). The NE Batter was in the process of final completion when the failure occurred. The failure was very large, it encompassed about six million cubic metres of material, was 500m long and occurred on a slope that was approximately 80m high. The failure occurred by a mechanism called block sliding, where a large block of coal slid horizontally across the mine floor. The failure extended as far back as the Latrobe River, which was completely diverted into the mine by the failure. There were two main causes for the failure. The principal cause was water pressure in a joint along the rear of the failure.