The Capitolium at Brescia in the Flavian Period

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

INQUADRAMENTO TERRITORIALE Desenzano Del Garda È Un Comune

INQUADRAMENTO TERRITORIALE Desenzano del Garda è un comune italiano di 28675 abitanti della provincia di Brescia, nel basso Lago di Garda, in Lombardia. Ha una superficie di 60 km2. Desenzano ha come frazioni Rivoltella del Garda e San Martino della Battaglia. Nel territorio comunale si trovano le uscite dell'Autostrada A4 “Desenzano del Garda” a sud-ovest dell'abitato e “Sirmione” a San Martino della Battaglia, confinante con il territorio di Sirmione. A breve distanza si trovano poi l'aeroporto di Villafranca di Verona e l'aeroporto di Brescia-Montichiari. Il territorio è attraversato dalla ferrovia Milano-Venezia sulla quale è ubicata la stazione ferroviaria di Desenzano del Garda-Sirmione. La città di Desenzano è dotata di una rete di trasporti automobilistici urbani gestita da Brescia Trasporti. Per quanto riguarda l'istruzione si trovano vari edifici tra cui scuole, biblioteche, musei e teatri. Gli amanti dello sport possono praticare il wind-surf, la mountain-bike e il volo libero. Per i giovani non mancano discoteche e bar. Inoltre si può passeggiare sul lungolago o sotto i portici della centrale Piazza Malvezzi. D'inverno il clima è temperato e senza nebbia e d'estate c'è la brezza che viene dal lago. IDENTIFICAZIONE DELL'AREA DI NOSTRO INTERESSE Il terreno oggetto di intervento, di proprietà del signor Bianchi, è situato in Via Rio Freddo, ha una superficie di 884 mq e confina con altri terreni ad uso residenziale. Si trova al confine di Desenzano, a pochi passi dal centro di Rivoltella e a pochi minuti dal lago. L'area è individuata nel PGT vigente nell'Ambito Residenziale Consolidato a media densità. -

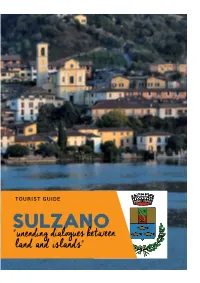

SULZANO " Unending Dialogues Between Land and Islands" SULZANO GUIDE 3

TOURIST GUIDE SULZANO " unending dialogues between land and islands" SULZANO GUIDE 3 SULZANO BACKGROUND HISTORY much quicker and soon small Sulzano derives its name from workshops were turned into actual Sulcius or Saltius. It is located in an factories providing a great deal of area where there was once an ancient employment. Roman settlement and was born as a lake port for the area of Martignago. Along with the economic growth came wealth and during the Twentieth Once, the fishermen’s houses were century the town also became a dotted along the shore and around tourist centre with new hotels and the dock from where the boats would beach resorts. Many were the noble leave to bring the agricultural goods to and middle-class families, from the market at Iseo and the materials Brescia and also from other areas, from the stone quarry of Montecolo, who chose Sulzano as a much-loved used for the production of cement, holiday destination and readily built would transit through here directed elegant lake-front villas. towards the Camonica Valley. At the beginning of the XVI century, the parish was moved to Sulzano and thus the lake town became more important and bigger than the hillside Sulzano is a village that overlooks the one. During the XVII Century, many Brescia side of the Iseo Lake mills were built to make the most of COMUNE DI the driving force of the water that SULZANO flowed abundantly along the valley to the south of the parish. Via Cesare Battisti 91- Sulzano (Bs) Tel. 030/985141 - Fax. -

4 Hours Roman Tour

ITALIA IN FERRARI powered by “Red Travel Roman Tour” Rome YOUR ULTIMATE DRIVING EXPERIENCE: DRIVE THE LATEST FERRARI MODELS ON A 4 HOURS’ TOUR. Imagine driving on winding roads through the hilltop villages along the Mille Miglia route. Now imagine having the exclusive opportunity of driving the latest Ferrari models in a four hours’ tour on the breathtaking roads nearby Rome on the Mille Miglia route. Ferrari F8 Tributo, Ferrari 488 Spider, Ferrari 488 Pista or Ferrari Portofino will be at your disposal, to let you discover which one suits you the best. The Roman Tour is a privilege dedicated to the guests of the best hotels in Italy, to the passengers of VIP cruises arriving in Rome, it’s a luxurious gift idea. Accelerate through those steep, winding roads of northern Latium, the individuality of each Ferrari putting your driving skills to the ultimate test. Every Ferrari has its own personality and a voice to match. Enjoy the full throttle roar of a new 8-cylinder turbo or sit back and feel the breeze in your hair at the wheel of a hard-top. Red Travel Roman Tour “Red Travel Roman Tour” Rome PROGRAMME ( 4 hours’ tour ) FERRARI TOUR ON THE MILLE MIGLIA ROUTE Meeting in Civitavecchia (Rome), at the “Sporting Yacht Club” at tourist harbour “Riva di Traiano”· or at the main cruise harbour, where the latest Ferrari models will be waiting for our guests. · Official Ferrari briefing with our Tour Director. Ferrari briefing Our private Tour Director, an expert Ferrari driver, will introduce our guests to the world of Ferrari; clarify the finer details of the controls, explain the differences between the various models (Ferrari F8 Tributo, Ferrari 488 Spider, Ferrari 488 Pista, Ferrari Portofino) and the engine (new 8-cylinder turbo) and most importantly, give guidance on how to handle the F1 paddle-gear shifting behind the steering wheel. -

Brescia University Athletics

BRESCIA UNIVERSITY ATHLETICS STUDENT-ATHLETE HANDBOOK www.bresciabearcats.edu Dear Brescia University Student-Athlete: WELCOME! We are very happy to have you here at Brescia University and as a member of our athletic department family. We are looking forward to another great year of success in the classroom and during competition. It takes tremendous commitment to be a student-athlete and we commend you for the dedication you have made to yourself and to this University. I also wanted to take a quick moment to introduce myself. I am in my second year as the athletic director at Brescia University and I am just as excited as you are to be starting a new season. Please know that my office is always open to you and that I am available whenever you might need assistance. To make things easier, I have scheduled open office hours every Monday during the school year from 3 p.m. – 4pm Science 128. Do not hesitate to come visit me if I can help you in any way. After this letter, you will find a copy of our student-athlete handbook. Within this handbook, you will find plenty of important information regarding a wide range of topics relating to being a student-athlete at Brescia University. I encourage you to read the handbook and ask any questions if you experience confusion about department policy. Please let me know if you have any questions and best of luck this season! Sincerely, Brian Skortz Athletic Director Brescia University 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS .................................................................................................................................... 2 DIRECTORY OF ATHLETIC DEPARTMENT STAFF .......................................................................................... -

S202 Invernale

Edizione del 3 Dicembre 2012 Slink 202 BRESCIA-SALO'-GARDONE RIVIERA-TOSCOLANO-GARGNANO / BRESCIA-VOBARNO-VESTONE - SERVIZIO INVERNALE ANDATA codice V02 S50 A50 B50 A52 B52 B54 P02 A54 A56 D58 A58 Y58 A60 B02 A62 A64 A66 A68 A70 A72 A74 P10 V72 A76 A78 V98 A80 A82 A84 W06 A86 B06 A88 A90 W12 A92 B92 B14 A94 B94 A96 B96 A98 codice V04 V16 W78 V22 V30 V36 V40 V42 V44 V48 V52 V60 V78 V90 W02 W04 W10 C89 W18 W20 W24 W30 W32 dettaglio 85S-3-2 P A BP1S54 1 A B3 1-F5 A B BRESCIA-Terminal SIA 05.45 05.55 06.10 06.25 06.40 06.55 07.00 07.10 07.25 07.40 07.55 08.10 08.40 08.45 09.10 09.40 10.10 10.40 11.10 11.40 12.10 12.10 12.25 12.40 13.10 13.40 14.10 14.40 14.40 15.10 15.25 15.40 16.10 16.25 16.40 16.55 17.10 17.10 17.25 17.40 17.55 18.10 BRESCIA-Porta Venezia 05.52 06.02 06.17 06.32 06.47 07.02 07.07 07.17 07.32 07.47 08.02 08.17 08.47 | 09.17 09.47 10.17 10.47 11.17 11.47 12.17 12.17 12.32 12.47 13.17 13.47 14.17 14.47 14.47 15.17 | 15.47 16.17 16.32 16.47 17.02 17.17 17.17 17.32 17.47 18.02 18.17 REZZATO-Ponte 06.06 06.19 06.34 06.49 07.04 07.19 07.24 07.34 07.49 08.04 08.19 08.34 09.04 | 09.34 10.04 10.34 11.04 11.34 12.04 12.34 12.34 12.49 13.04 13.34 14.04 14.34 15.04 15.04 15.34 | 16.04 16.34 16.49 17.04 17.19 | 17.34 17.49 18.04 18.19 18.34 MAZZANO 06.10 06.25 06.40 06.55 07.10 07.25 07.30 07.40 07.55 08.10 08.25 08.40 09.10 | 09.40 10.10 10.40 11.10 11.40 12.10 12.40 12.40 12.55 13.10 13.40 14.10 14.40 15.10 15.10 15.40 | 16.10 16.40 16.55 17.10 17.25 | 17.40 17.55 18.10 18.25 18.40 NUVOLERA 06.13 06.28 06.43 06.58 07.13 07.28 07.33 -

ENG AUTOBSPD 31 12 2018 Fascicolo Completo Bilancio

TABLE OF CONTENTS CORPORATE BOARDS AND OFFICERS ........................................................................................................ 8 REPORT ON OPERATIONS ................................................................................................................................ 9 Overview ................................................................................................................................................................. 9 1 Business performance .................................................................................. 9 1.1 Results of operations ........................................................................................................................... 9 1.2 Cash flows .............................................................................................................................................. 11 1.3 Financial position ................................................................................................................................. 12 2 Motorway operation .....................................................................................13 2.1 Traffic ....................................................................................................................................................... 13 2.2 Accident rates ....................................................................................................................................... 17 2.3 Toll rates ................................................................................................................................................ -

Brescian Trails Hiking in the Province of Brescia - Brescia, Provincia Da Scoprire Bibliography

Brescian Trails Hiking in the Province of Brescia www.rifugi.lombardia.it - www.provincia.bs.it Brescia, provincia da scoprire Bibliography Grafo Edolo, l’Aprica e le Valli di S. Antonio, 2010 Le Pertiche nel cuore della Valsabbia, 2010 Gargnano tra lago e monte, 2010 I colori dell’Alto Garda: Limone e Tremosine, 2008 Il gigante Guglielmo tra Sebino e Valtrompia, 2008 L’Alta Valcamonica e i sentieri della Guerra Bianca, 2008 L’antica via Valeriana sul lago d’Iseo, 2008 Sardini Editrice Guida ai sentieri del Sebino Bresciano, 2009 Guida al Lago d’Iseo, 2007 Parco Adamello Guida al Parco dell’Adamello Provincia di Brescia Parco dell’Adamello Uffici IAT - Informazione e Accoglienza Turistica Sentiero Nr1, Alta Via dell’Adamello Brescia Lago di Garda Piazza del Foro 6 - 25121 Brescia Desenzano del Garda Ferrari Editrice Tel. 0303749916 Fax 0303749982 Via Porto Vecchio 34 [email protected] 25015 Desenzano del Garda I Laghi Alpini di Valle Camonica Vallecamonica Tel. 0303748726 Fax 0309144209 [email protected] Associazione Amici Capanna Lagoscuro Darfo Boario Terme Il Sentiero dei Fiori Piazza Einaudi 2 Gardone Riviera 25047 Darfo Boario Terme Corso Repubblica 8 - 25083 Gardone Riviera Tel. 0303748751 Fax 0364532280 Tel. 0303748736 Fax 036520347 Nordpress [email protected] [email protected] Il sentiero 3v Edolo Salò La Val d’Avio Piazza Martiri Libertà 2 - 25048 Edolo Piazza Sant’Antonio 4 - 25087 Salò Tel. 0303748756 Fax 036471065 Tel. 0303748733 Fax 036521423 [email protected] [email protected] Ponte di Legno Sirmione Corso Milano 41 Viale Marconi 6 - 25019 Sirmione Maps 25056 Ponte di Legno Tel. -

Franciacorta Shines with Chardonnay

PETER DRY Franciacorta shines with Chardonnay HERE IS Franciacorta? You might well ask. Outside of Italy the region and its wines are W virtually unknown. Although wine has been produced here since ancient times, the modern wine indus- try is young by Italian standards. Until the 1960s, the pleas- ant but undistinguished table wines of the region were con- sumed locally. Today, the region is synonymous with high quality sparkling wine. The development of the sparkling wine industry here is an interesting case study because it appears to have been one of those rare instances where the end product was chosen before the suitability of the grape material had been confirmed. For example, two major Italian wine companies, Bellavista and Ca’ del Bosco, decided to invest in the region (for economic reasons) in order to expand their production of sparkling wine. The market demand for the resultant product was good and, fortuitously, the region turned out to be a good location for Chardonnay grapes for sparkling wine. The vineyards of Franciacorta are found in rolling hills to the south of Lake Iseo in central Lombardy, 20 km Peter Dry west of Brescia and 60 km east of Milan. Lombardy is the Vineyards of the World largest and most populous region of Italy. In addition to Franciacorta, its wine-producing regions include Oltrepò Paese in the southwest, Valtellina in the north and Lugana and Riviera del Garda Bresciano in the east. The munities ( curtes ) were allowed to be free ( francae ) of taxes. name of the region may be derived from Francae curtes , a Since 1995, use of the Franciacorta name has been permit- reference to the small communities of Benedictine ted solely for Denominazione di Origine Controllata e Garantita monks who settled in the region in 1100 AD—the com- (DOCG) sparkling wines made by the methode champenoise . -

LS026 Brescia-Castegnato-Palazzolo

LS026 BRESCIA - ROVATO - PALAZZOLO/CHIARI - PONTOGLIO Andata - Towards Palazzolo Orario Feriale in vigore dal 09 Giugno 2021 Fer Fer Fer Fer Fer5 Fer Fer Brescia-Terminal Via Togni 06:20 13:30 14:40 18:30 Brescia-Via dei Mille 06:23 13:33 14:43 18:33 Brescia-Via Valle Camonica Mandolossa 06:40 13:41 14:51 18:41 Castegnato-Via Trebeschi (Centro) 06:45 13:51 15:01 18:51 Castegnato-S.P. Baitella 06:48 13:56 15:06 18:56 Ospitaletto-Via X Giornate Palazzetto 07:00 14:00 15:10 19:00 Cazzago S.M.-Bivio Bertola 07:05 14:04 15:14 19:04 Rovato-Via XXV Aprile Cityper 05:50 07:10 07:20 07:15 14:08 15:18 19:08 © Coincidenza © Coccaglio-Piazza Marenzio 05:55 07:27 07:20 14:13 15:23 19:13 Chiari-Stazione FS 06:05 07:35 14:21 Cologne-Via Brescia Bivio Chiari 07:25 15:28 19:18 Palazzolo-Piazzale Kennedy Palazzolo-Via Torre del Popolo Municipio 07:35 15:38 19:28 Operatore/Operator: Arriva Italia - Sede di Brescia Le fermate indicate sull'orario sono un estratto dell'intera corsa. Per l'elenco completo utilizzare il info: www.arriva.it / 840620001 / Via Cassala 3A Brescia travel planner sul sito arriva.it o l'app MoveMe Brescia 1/2 The stops shown are a selection of the stops for this route. Use the travel planner on arriva.it or Legenda: the app MoveMe Brescia for a complete list of all stops Fer - Si effettua dal Lunedì al Sabato Fer5 - Si effettua dal Lunedì al Venerdì Info Note: LS026 © - Coincidenza per Palazzolo con linea da Brescia (LS025) LS026 BRESCIA - ROVATO - PALAZZOLO/CHIARI - PONTOGLIO Ritorno - Towards Brescia Orario Feriale in vigore dal 09 Giugno 2021 1 Fer5 Fer Fer Fer Fer5 Fer Chiari-Stazione FS 07:00 07:35 Palazzolo-Via Torre del Popolo Municipio 05:30 11:30 13:05 15:40 Cologne-Via Brescia Bivio Chiari 05:40 11:40 13:15 15:50 Coccaglio-Piazza Marenzio 05:45 07:10 07:45 11:45 13:20 15:55 © Coincidenza © Rovato-Via XXV Aprile Cityper 05:50 07:15 07:53 11:50 13:25 16:00 Cazzago S.M.-Bivio Bertola 08:17 11:54 13:29 16:04 Ospitaletto-Via Martiri Libertà (Oratorio) 08:21 11:58 13:33 16:08 Castegnato-S.P. -

LN026 Desenzano-Verona.Xlsx

ORARIO IN VIGORE dal 13 SETTEMBRE 2021 Linea LN026 edizione 13 Settembre 2021 ANDATA Contact center 035 289000 - Numero verde 800 139392 (solo da rete fissa) www.arriva.it BRESCIA-DESENZANO-SIRMIONE-PESCHIERA-VERONA Stagionalità corsa FER SCO FER SCO SCO FER SCO FER SCO SCO FER FER FER FER FER FER FER SCO FER FER FER FER FER FER FER FER FER FEST FEST FEST FEST FEST FEST FEST FEST FEST FEST FEST FEST FEST FEST FEST Giorni di effettuazione 123456 123456 123456 123456 123456 123456 12345 123456 123456 123456 123456 123456 123456 123456 123456 123456 123456 123456 123456 12345 123456 123456 123456 123456 123456 123456 123456 NOTE: B A CCCCCCDC BRESCIA -- Autostazione Via Solferino 6:05 6:30 6:55 7:10 8:10 9:10 10:10 11:10 11:40 12:10 13:10 14:00 14:10 15:10 16:10 17:10 18:10 19:10 20:05 7:10 8:10 9:10 10:10 11:10 12:10 13:10 14:10 15:10 16:10 17:10 18:10 18:10 19:10 BRESCIA - Via XX Settembre Porta Cremona 6:07 6:32 6:57 7:12 8:12 9:12 10:12 11:12 11:42 12:12 13:12 14:02 14:12 15:12 16:12 17:12 18:12 19:12 20:07 7:12 8:12 9:12 10:12 11:12 12:12 13:12 14:12 15:12 16:12 17:12 18:12 18:12 19:12 BRESCIA - Porta Venezia, 10 6:11 6:36 7:16 8:16 9:16 10:16 11:16 11:46 12:16 13:16 14:06 14:16 15:16 16:16 17:16 18:16 19:16 20:11 7:16 8:16 9:16 10:16 11:16 12:16 13:16 14:16 15:16 16:16 17:16 18:16 18:16 19:16 BRESCIA - Sant'Eufemia 6:20 6:45 7:05 7:25 8:25 9:25 10:25 11:25 11:55 12:25 13:25 14:15 14:25 15:25 16:25 17:25 18:25 19:25 20:20 7:25 8:25 9:25 10:25 11:25 12:25 13:25 14:25 15:25 16:25 17:25 18:25 18:25 19:25 REZZATO - S.S.11 "Continente" 6:25 -

ART and CULTURE INDEX CITY of ART

ART and CULTURE INDEX CITY OF ART . pag. 4 SANTA GIULIA CITY MUSEUM . pag. 6 The Monumental Complex of San Salvatore-Santa Giulia THE ROMAN AGE . pag. 8 DISCOVERING BRESCIA . pag. 10 Piazza del Foro and Capitolium (Capitolium temple) The Castle, Arms Museum and Risorgimento Museum Teatro Grande and the International Piano Festival Duomo Nuovo Duomo Vecchio Tosio Martinengo Art Gallery Diocesan Museum AROUND BRESCIA . pag. 14 Musil Pinac – Aldo Cibaldi International Children At Gallery Mazzucchelli Museums Mille Miglia Museum National Museum of Photography Marble Route LAKE GARDA . .. pag. 18 Vittoriale degli Italiani Rocca and Ugo Da Como House-Museum Isola del Garda Prehistorical pile-dwellings in the alps Catullus’ Grotto and Sirmione Castle Rome and the middle ages on the shores of the lake The places of the Republic of Salò Tower of St. Martino The paper valley CAMONICA VALLEY . pag. 22 Archeopark Cerveno Via Crucis Romanino route Adamello White War Museum TROMPIA VALLEY . pag. 26 Paul VI Collection of contemporary art Iron and Mine Route Sacred Art Route The forest narrates Other museums SABBIA VALLEY . pag. 30 The sacred and the profane Bagolino Carnival Rocca d’Anfo LAKE ISEO AND FRANCIACORTA . pag. 32 Monastery of San Pietro in Lamosa Rodengo Saiano Olivetan abbey Via Valeriana, between the Lake and the valley Ome forge BRESCIA PLAIN . pag. 34 Tiepolo in Verolanuova Padernello Castle PHOTO CREDITS: Thanks to: Assessorato al Turismo - Comune di Brescia, Archivio fotografico Musei Civici d’Arte e Storia, Fondazione Brescia Musei, Fondazione Pinac, Musei Mazzucchelli, Fondazione Ugo Da Como, Fondazione Il Vittoriale degli italiani, Centro camuno di studi preistorici, Bresciainvetrina, Mediateca del SIBCA di Valle Trompia. -

COMUNE DI ADRO Provincia Di Brescia ___SETTORE

COMUNE DI ADRO Provincia di Brescia _______ SETTORE AMMINISTRATIVO FINANZIARIO PROGRAMMAZIONE DETERMINA N. 0453 DEL 19.12.2017 OGGETTO: DETERMINAZIONE A CONTRATTARE, TRAMITE RDO SU SINTEL, AFFIDAMENTO DEL SERVIZIO DI REDAZIONE ATTI CONTABILI RELATIVAMENTE ALL’ANNO 2018. CIG: ZB92164A31 DELl 19/12/2017. IL RESPONSABILE DI P.O. DEL SETTORE AMMINISTRATIVO – FINANZIARIO - PROGRAMMAZIONE − PREMESSO CHE: o la nuova contabilità armonizzata (introdotta con il D.Lgs 118 del 2011) ha comportato l’introduzione d’innumerevoli nuovi adempimenti; o è necessario l’intervento da parte di ditte specializzate al fine di avere un supporto per il controllo dello stato di avanzamento degli adempimenti richiesti, di verifica di quanto effettuato e di supporto al fine di rispettare quanto richiesto dal D.Lgs 118/2011; o nel corso dell’anno 2018 bisognerà provvedere all’istruttoria e predisposizione dei documenti relativi al DUP, al bilancio di previsione, al rendiconto della gestione, alla verifica dello stato di attuazione dei programmi e degli equilibri di bilancio, all’invio telematico alla Corte dei Conti dei file XML del rendiconto di gestione; − SENTITA la ditta Scriba Brescia s.r.l., specializzata in supporto ai servizi finanziari Enti Locali, la quale si è resa disponibile a supportare l’ufficio per quanto sopra espresso; − VISTO il disciplinare tecnico per il servizio di redazione atti contabili anno 2018, allegato alla presente determina; − PRESO ATTO CHE o l’art. 328 del D.P.R. del 5 ottobre 2010 n. 207 “Regolamento di esecuzione ed attuazione del Codice dei Contratti Pubblici D.Lgs. n. 163/2006” in attuazione delle Direttive 2004/17/CE e 2004/18/CE introduce una disciplina di dettaglio per il Mercato Elettronico di cui all’art.