John C. Haughey Ilia Delio

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sacred Rhetorical Invention in the String Theory Movement

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Communication Studies Theses, Dissertations, and Student Research Communication Studies, Department of Spring 4-12-2011 Secular Salvation: Sacred Rhetorical Invention in the String Theory Movement Brent Yergensen University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/commstuddiss Part of the Speech and Rhetorical Studies Commons Yergensen, Brent, "Secular Salvation: Sacred Rhetorical Invention in the String Theory Movement" (2011). Communication Studies Theses, Dissertations, and Student Research. 6. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/commstuddiss/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Communication Studies, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Communication Studies Theses, Dissertations, and Student Research by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. SECULAR SALVATION: SACRED RHETORICAL INVENTION IN THE STRING THEORY MOVEMENT by Brent Yergensen A DISSERTATION Presented to the Faculty of The Graduate College at the University of Nebraska In Partial Fulfillment of Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Major: Communication Studies Under the Supervision of Dr. Ronald Lee Lincoln, Nebraska April, 2011 ii SECULAR SALVATION: SACRED RHETORICAL INVENTION IN THE STRING THEORY MOVEMENT Brent Yergensen, Ph.D. University of Nebraska, 2011 Advisor: Ronald Lee String theory is argued by its proponents to be the Theory of Everything. It achieves this status in physics because it provides unification for contradictory laws of physics, namely quantum mechanics and general relativity. While based on advanced theoretical mathematics, its public discourse is growing in prevalence and its rhetorical power is leading to a scientific revolution, even among the public. -

The Shape of Inner Space: String Theory and the Geometry of the Universe's Hidden Dimensions

[PDF] The Shape Of Inner Space: String Theory And The Geometry Of The Universe's Hidden Dimensions Shing-Tung Yau, Steve Nadis - download pdf free book The Shape Of Inner Space: String Theory And The Geometry Of The Universe's Hidden Dimensions PDF, The Shape Of Inner Space: String Theory And The Geometry Of The Universe's Hidden Dimensions Download PDF, Read Online The Shape Of Inner Space: String Theory And The Geometry Of The Universe's Hidden Dimensions E-Books, Read The Shape Of Inner Space: String Theory And The Geometry Of The Universe's Hidden Dimensions Full Collection Shing-Tung Yau, Steve Nadis, I Was So Mad The Shape Of Inner Space: String Theory And The Geometry Of The Universe's Hidden Dimensions Shing- Tung Yau, Steve Nadis Ebook Download, PDF The Shape Of Inner Space: String Theory And The Geometry Of The Universe's Hidden Dimensions Free Download, Read Online The Shape Of Inner Space: String Theory And The Geometry Of The Universe's Hidden Dimensions Ebook Popular, online free The Shape Of Inner Space: String Theory And The Geometry Of The Universe's Hidden Dimensions, Download Online The Shape Of Inner Space: String Theory And The Geometry Of The Universe's Hidden Dimensions Book, Download PDF The Shape Of Inner Space: String Theory And The Geometry Of The Universe's Hidden Dimensions, Download pdf The Shape Of Inner Space: String Theory And The Geometry Of The Universe's Hidden Dimensions, Read Best Book Online The Shape Of Inner Space: String Theory And The Geometry Of The Universe's Hidden Dimensions, Read Online The -

String Theory, Einstein, and the Identity of Physics: Theory Assessment in Absence of the Empirical

String theory, Einstein, and the identity of physics: Theory assessment in absence of the empirical Jeroen van Dongen Institute for Theoretical Physics Vossius Center for History of the Humanities and Sciences University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, The Netherlands Abstract String theorists are certain that they are practicing physicists. Yet, some of their recent critics deny this. This paper argues that this conflict is really about who holds authority in making rational judgment in theoretical physics. At bottom, the conflict centers on the question: who is a proper physicist? To illustrate and understand the differing opinions about proper practice and identity, we discuss different appreciations of epistemic virtues and explanation among string theorists and their critics, and how these have been sourced in accounts of Einstein’s biography. Just as Einstein is claimed by both sides, historiography offers examples of both successful and unsuccessful non-empirical science. History of science also teaches that times of conflict are often times of innovation, in which novel scholarly identities may come into being. At the same time, since the contributions of Thomas Kuhn historians have developed a critical attitude towards formal attempts and methodological recipes for epistemic demarcation and justification of scientific practice. These are now, however, being considered in the debate on non-empirical physics. Introduction Theoretical high energy physics is in crisis. Many physicists may wish to deny this, but it is richly illustrated by the heated exchanges, charged manifestos and exclamations of despair in highly visible publications. For example, three prominent cosmologists, Anna Ijjas, Paul Steinhardt and Abraham Loeb, argued in the February 2017 issue of Scientific American that the long favoured model for the early universe, inflationary cosmology, has no data to support it and has gone through so many patch-ups that it is now beyond testability. -

INFORMATION– CONSCIOUSNESS– REALITY How a New Understanding of the Universe Can Help Answer Age-Old Questions of Existence the FRONTIERS COLLECTION

THE FRONTIERS COLLECTION James B. Glattfelder INFORMATION– CONSCIOUSNESS– REALITY How a New Understanding of the Universe Can Help Answer Age-Old Questions of Existence THE FRONTIERS COLLECTION Series editors Avshalom C. Elitzur, Iyar, Israel Institute of Advanced Research, Rehovot, Israel Zeeya Merali, Foundational Questions Institute, Decatur, GA, USA Thanu Padmanabhan, Inter-University Centre for Astronomy and Astrophysics (IUCAA), Pune, India Maximilian Schlosshauer, Department of Physics, University of Portland, Portland, OR, USA Mark P. Silverman, Department of Physics, Trinity College, Hartford, CT, USA Jack A. Tuszynski, Department of Physics, University of Alberta, Edmonton, AB, Canada Rüdiger Vaas, Redaktion Astronomie, Physik, bild der wissenschaft, Leinfelden-Echterdingen, Germany THE FRONTIERS COLLECTION The books in this collection are devoted to challenging and open problems at the forefront of modern science and scholarship, including related philosophical debates. In contrast to typical research monographs, however, they strive to present their topics in a manner accessible also to scientifically literate non-specialists wishing to gain insight into the deeper implications and fascinating questions involved. Taken as a whole, the series reflects the need for a fundamental and interdisciplinary approach to modern science and research. Furthermore, it is intended to encourage active academics in all fields to ponder over important and perhaps controversial issues beyond their own speciality. Extending from quantum physics and relativity to entropy, conscious- ness, language and complex systems—the Frontiers Collection will inspire readers to push back the frontiers of their own knowledge. More information about this series at http://www.springer.com/series/5342 For a full list of published titles, please see back of book or springer.com/series/5342 James B. -

The Elegant Universe

The Elegant Universe Teacher’s Guide On the Web It’s the holy grail of physics—the search for the ultimate explanation of how the universe works. And in the past few years, excitement has grown among NOVA has developed a companion scientists in pursuit of a revolutionary approach to unify nature’s four Web site to accompany “The Elegant fundamental forces through a set of ideas known as superstring theory. NOVA Universe.” The site features interviews unravels this intriguing theory in its three-part series “The Elegant Universe,” with string theorists, online activities based on physicist Brian Greene’s best-selling book of the same name. to help clarify the concepts of this revolutionary theory, ways to view the The first episode introduces string theory, traces human understanding of the program online, and more. Find it at universe from Newton’s laws to quantum mechanics, and outlines the quest www.pbs.org/nova/elegant/ for and challenges of unification. The second episode traces the development of string theory and the Standard Model and details string theory’s potential to bridge the gap between quantum mechanics and the general theory of relativity. The final episode explores what the universe might be like if string theory is correct and discusses experimental avenues for testing the theory. Throughout the series, scientists who have made advances in the field share personal stories, enabling viewers to experience the thrills and frustrations of physicists’ search for the “theory of everything.” Program Host Brian Greene, a physicist who has made string theory widely accessible to public audiences, hosts NOVA’s three-part series “The Elegant Universe.” A professor of physics and mathematics at Columbia University in New York, Greene received his undergraduate degree from Harvard University and his doctorate from Oxford University, where he was a Rhodes Scholar. -

From Experience to Metaphor, by Way of Imagination

From Experience to Metaphor, by Way of Imagination Sean M. Carroll Enrico Fermi Institute, Department of Physics, and Kavli Institute for Cosmological Physics, University of Chicago 5640 S. Ellis Avenue, Chicago, IL 60637, USA [email protected] Abstract Modern science deals with concepts and techniques that reach far beyond the famil- iar realm of everyday experience. In attempting to account for the behavior of nature in these extreme situations, scientists are forced to propose dramatically counter-intuitive ideas, views of the universe that would be impossible to invent without the pressure of conforming to data from extreme regions of space and time. Precisely because these ideas seem startling and alien, they can provide unique metaphorical source material for literary creators. 1 On the surface, science and literature would appear to be, if not precisely opposites, at least quite distinct fields of endeavor. Science searches for an understanding of reality through empirical methods, while literature is in the business of imagining alternatives to the real world. Indeed, the dictionary on my shelf [1] offers this as the relevant definition of literature: all writings in prose or verse, especially those of an imaginative or critical charac- ter, without regard to their excellence: often distinguished from scientific writing, news reporting, etc. Imagination is key: in science our imagination is shackled by the imperative of conforming to reality, while in literature it is allowed to roam freely. And yet, these superficially dissimilar -

Hep-Th/0207244V2 16 Sep 2002 Eray1 2008 1, February Rva Xml Fatplg Hnigtasto Ihonly with Transition Changing Topology I a a This on of flux

February 1, 2008 hep-th/0207244 MIT-CTP-3284 HUTP-02/A014 DAMTP-2002-85 Conifold Transitions and Five-Brane Condensation in M-Theory on Spin(7) Manifolds Sergei Gukov1, James Sparks2, and David Tong3 1Jefferson Physical Laboratory, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA 02138, U.S.A. [email protected] 2Centre for Mathematical Sciences, University of Cambridge, Wilberforce Road, Cambridge CB3 0WA, UK. [email protected] 3Center for Theoretical Physics, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA 02139, U.S.A. [email protected] arXiv:hep-th/0207244v2 16 Sep 2002 Abstract We conjecture a topology changing transition in M-theory on a non-compact asymptotically conical Spin(7) manifold, where a 5-sphere collapses and a CP2 bolt grows. We argue that the transition may be understood as the condensation of M5-branes wrapping S5. Upon reduction to ten dimensions, it has a physical interpretation as a transition of D6-branes lying on calibrated submanifolds of flat space. In yet another guise, it may be seen as a geometric transition between two phases of type IIA string theory on a G2 holonomy manifold with either wrapped D6-branes, or background Ramond-Ramond flux. This is the first non- trivial example of a topology changing transition with only 1/16 supersymmetry. Contents 1 Introduction 1 2 D6-Branes, M-Theory and Spin(7) Conifolds 7 2.1 D6-Branes and the Cone over SO(5)/SO(3) ............... 8 2.2 D6-Branes and the Cone over SU(3)/U(1) ................ 10 2.3 DeformationsofCoassociativeCones . ... 12 2.4 AnomaliesandSupersymmetry . -

Music, Mediation, and Superstrings: the Quest for Universal Harmony

Journal of Dispute Resolution Volume 2005 Issue 2 Article 1 2005 Music, Mediation, and Superstrings: The Quest for Universal Harmony John W. Cooley Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.missouri.edu/jdr Part of the Dispute Resolution and Arbitration Commons Recommended Citation John W. Cooley, Music, Mediation, and Superstrings: The Quest for Universal Harmony, 2005 J. Disp. Resol. (2005) Available at: https://scholarship.law.missouri.edu/jdr/vol2005/iss2/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at University of Missouri School of Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Dispute Resolution by an authorized editor of University of Missouri School of Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Cooley: Cooley: Music, Mediation, and Superstrings JOURNAL OF DISPUTE RESOLUTION VOLUME 2005 NUMBER 2 ARTICLES Music, Mediation, and Superstrings: The Quest for Universal Harmony John W. Cooley* I. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................. 227 II. SUPERSTRING THEORY AND UNIVERSAL HARMONY: AN OVERVIEW ........... 229 III. MUSIC AND MEDICATION AS PROBLEM SOLVING ARTS ................................ 235 IV. THE TECHNIQUES OF A MASTER COMPOSER, PERFROMER, AND PROBLEM SO LV ER .......................................................................................................24 2 V. THE MUSICAL ELEMENTS OF MEDIATION .................................................... -

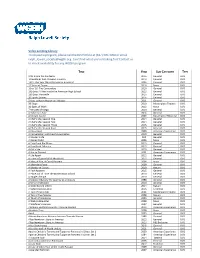

Video Lending Library to Request a Program, Please Call the RLS Hotline at (617) 300-3900 Or Email Ralph Lowell [email protected]

Video Lending Library To request a program, please call the RLS Hotline at (617) 300-3900 or email [email protected]. Can't find what you're looking for? Contact us to check availability for any WGBH program. TITLE YEAR SUB-CATEGORY TYPE 9/11 Inside the Pentagon 2016 General DVD 10 Buildings that Changed America 2013 General DVD 1421: The Year China Discovered America? 2004 General DVD 15 Years of Terror 2016 Nova DVD 16 or ’16: The Contenders 2016 General DVD 180 Days: A Year inside the American High School 2013 General DVD 180 Days: Hartsville 2015 General DVD 20 Sports Stories 2016 General DVD 3 Keys to Heart Health Lori Moscas 2011 General DVD 39 Steps 2010 Masterpiece Theatre DVD 3D Spies of WWII 2012 Nova DVD 7 Minutes of Magic 2010 General DVD A Ballerina’s Tale 2015 General DVD A Certain Justice 2003 Masterpiece Mystery! DVD A Chef’s Life, Season One 2014 General DVD A Chef’s Life, Season Two 2014 General DVD A Chef’s Life, Season Three 2015 General DVD A Chef’s Life, Season Four 2016 General DVD A Class Apart 2009 American Experience DVD A Conversation with Henry Louis Gates 2010 General DVD A Danger's Life N/A General DVD A Daring Flight 2005 Nova DVD A Few Good Pie Places 2015 General DVD A Few Great Bakeries 2015 General DVD A Girl's Life 2010 General DVD A House Divided 2001 American Experience DVD A Life Apart 2012 General DVD A Lover's Quarrel With the World 2012 General DVD A Man, A Plan, A Canal, Panama 2004 Nova DVD A Moveable Feast 2009 General DVD A Murder of Crows 2010 Nature DVD A Path Appears 2015 General -

Brian Green: the Fabric of the Cosmos. Space Time and the Texture Of

Brian Greene - The Fabric Of The Cosmos.htm THIS IS A BORZOI BOOK PUBLISHED BY ALFRED A. KNOPF Copyright © 2004 by Brian R. Greene All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, and in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto. Distributed by Random House, Inc., New York. www.aaknopf.com Knopf, Borzoi Books, and the colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Greene, B. (Brian). The fabric of the cosmos : space, time, and the texture of reality / Brian Greene. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references (pp. 543-44). ISBN 0-375-41288-3 1. Cosmology—Popular works. I. Title. QB982.G74 2004 523.1—dc22 2003058918 Manufactured in the United States of America First Edition file:///E|/temp/greene/Brian%20Greene%20-%20The%20Fabric%20Of%20The%20Cosmos-htm/Brian%20Greene%20-%20The%20Fabric%20Of%20The%20Cosmos.htm (1 de 740)24/05/2005 21:29:47 Brian Greene - The Fabric Of The Cosmos.htm To Tracy file:///E|/temp/greene/Brian%20Greene%20-%20The%20Fabric%20Of%20The%20Cosmos-htm/Brian%20Greene%20-%20The%20Fabric%20Of%20The%20Cosmos.htm (2 de 740)24/05/2005 21:29:47 Brian Greene - The Fabric Of The Cosmos.htm Contents file:///E|/temp/greene/Brian%20Greene%20-%20The%20Fabric%20Of%20The%20Cosmos-htm/Brian%20Greene%20-%20The%20Fabric%20Of%20The%20Cosmos.htm (3 de 740)24/05/2005 21:29:47 Brian Greene - The Fabric Of The Cosmos.htm Preface ix Parti REALITY'S ARENA 1. -

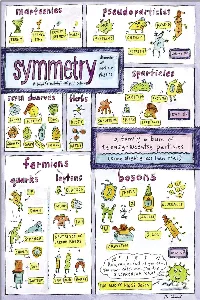

May 2007.Pdf

volume 04 | issue 04 | may 07 symmetryA joint Fermilab/SLAC publication On the cover Roz Chast is best known for her cartoons in The New Yorker, more than 800 of which have appeared since 1978. But she’s no stranger to the sciences, having published in both The Sciences and Scientific American. She has written and illustrated several books, most recently Theories of Everything: Selected, Collected, and Health-Inspected Cartoons 1978–2006, and collaborated with Steve Martin on a children’s book that is scheduled to come out in October. Office of Science U.S. Department of Energy contents 2 Editorial: 3 Commentary: 4 Signal to Background A Public Hunger for Physics Sherry Yennello Say it in Russian; a quick how-to; The general public seems to Whether scientific meetings a zappy show; sports cars and want particle physics as part of provide childcare is much more cavities; radioactive people; farm- their intellectual, cultural, and than a matter of convenience. family reunion; tracking dark personal lives. energy; name that particle; letters 10 The Search for Dark 16 The Great String Debate 22 When the New Energy When Brian Greene and Neighbor’s a Giant What is this stuff that fills the Lawrence Krauss tangle over At one potential site for the vacuum of space, accelerates string theory, wisecracks fly. International Linear Collider, the expansion of the universe, people in the community are and accounts for 70 percent of getting to know the project everything? More than two dozen years in advance. experiments aim to find out. 28 Day in the Life: 30 Gallery: 32 Essay: Katie and Adam Yurkewicz Ken McMullen Launched into Science In the move from Fermilab to He calls his latest work a “very “Reading about science was not CERN, a $10 globe, 100 plastic radical new form of cinema” quite enough. -

Greene, Brian. the Elegant Universe: Superstrings, Hidden Dimensions and the Quest for the Ultimate Theory

Greene, Brian. The Elegant Universe: Superstrings, Hidden Dimensions and the Quest for the Ultimate Theory. New York: Vintage Books, 2000, 448pp. Outline Prepared by Rev. William S. Wick, Norwich University Chaplain (12/18/2013) I. Preface p.ix A. During the last thirty years of his life, Albert Einstein sought [but never realized] a so-called unified field theory capable of describing nature’s forces within a single, all-encompassing, coherent framework. B. ... physicists believe they have found a framework for stitching these insights together into a seamless whole - capable of describing all phenomena: superstring theory. p.x C. Elegant Universe is an attempt to make these insights accessible to a broad spectrum of readers. D. Superstring theory draws on many of the central discoveries in physics (and Greene focuses on the evolving understanding of space and time). E. ... cutting-edge research has integrated [Einstein’s] discoveries into a quantum universe with numerous hidden dimensions coiled into the fabric of the cosmos - dimensions whose geometry may well hold the key to some of the most profound questions ever posed. p.xi F. Greene’s has focuses on the impact superstring theory has on concepts of space and time. II. Part I: The Edge of Knowledge (Chapter One: Tied Up with String) p.1 A. Introduction p.3 1. two foundational pillars upon which modern physics rests: a. Albert Einstein’s General Relativity (a theoretical framework for understanding the universe on the largest of scales (the immense expanse of the universe itself) b. quantum mechanics (a theoretical framework for understanding the universe on the smallest of scales - (atomic/subatomic particles) 2.