Notes on the Federal Issue Sack Coat

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New 3 Season Jacket Trousers – 3 Great Fabrics

® LIBERTYUniform SOFT SHELL JACKET/LINING NEW 3 SEASON SHIRTS JACKET TROUSERS With Softshell Liner P. 3 OUTERWEAR Law Enforcement, Security, EMS, Fire Department, Corporate Liberty’s BEST ALL SHIRTS RAINWEAR THE BETTER COST EFFECTIVE Well priced & Well Made P. 5 JOB SHIRT FD Blouse Coat with ™ FABRIC Matching Trousers COMFORT ZONE MADE IN THE REVERSIBLE (Hint: Nanotex® Certified) P. 20 P. 13 3 Must-Have Garments U.S.A. P. 14 & 16 P. 14-15 TROUSERS – 3 GREAT FABRICS P.16-17 2018 EDITION - XI WHAT’S NEW AT LIBERTY UNIFORM? 3 NEW OUTERWEAR 1 HIGH-VIS PRODUCT LINE Liberty has added some great new waterproof jackets to our line: Liberty offers an expanding ANSI 3 compliant #575MFL 3-Season ANSI 3 jacket including a product line that is value priced with great soft shell liner/jacket attention to functional features and quality: #574 Convertible Jacket #524MBK & 524MNV – Reversible Police Windbreaker (see pg. 7) #578 Soft Shell Jacket/liner #561MFL – Windbreaker The separate soft shell jacket #578 can be zipped (see pg. 8) into #574 jacket to become a removable liner. (See pg. 3) #566MFL – Polar Parka (see pg. 4) #575MFL – 3-Season Jacket with Soft Shell liner/jacket (see pg. 3) 4 THE FINEST SYNTHETIC FABRIC #586MFL – 49” Reversible Raincoat with IN THE UNIFORM INDUSTRY Removable/Reversible Hood (see pg. 5) Direct from Burlington® Worldwide, maker of the finest uniform fabrics for military and law #587MFL – 30” Reversible Rain Jacket with enforcement, Liberty offers our exclusive COMFORT Removable/Reversible Hood ZONE® shirts and trousers with USA made fabrics. (see pg. -

Approximate Weight of Goods PARCL

PARCL Education center Approximate weight of goods When you make your offer to a shopper, you need to specify the shipping cost. Usually carrier’s shipping pricing depends on the weight of the items being shipped. We designed this table with approximate weight of various items to help you specify the shipping costs. You can use these numbers at your carrier’s website to calculate the shipping price for the particular destinations. MEN’S CLOTHES Item Weight in grams Item Weight in grams Underpants 70 - 100 Jacket 1000 - 1200 Sports shirt, T-shirt 220 - 300 Coat, duster 900 - 1500 UnderpantsShirt 70120 - -100 180 JacketWind-breaker 1000800 - -1200 1200 SportsBusiness shirt, suit T-shirt 2201200 - -300 1800 Coat,Autumn duster jacket 9001200 - -1500 1400 Sports suit 1000 - 1300 Winter jacket 1400 - 1800 Pants 600 - 700 Fur coat 3000 - 8000 Jeans 650 - 800 Hat 60 - 150 Shorts 250 - 350 Scarf 90 - 250 UnderpantsJersey 70450 - -100 600 JacketGloves 100080 - 140 - 1200 SportsHoodie shirt, T-shirt 220270 - 300400 Coat, duster 900 - 1500 WOMEN’S CLOTHES Item Weight in grams Item Weight in grams Underpants 15 - 30 Shorts 150 - 250 Bra 40 - 70 Skirt 200 - 300 Swimming suit 90 - 120 Sweater 300 - 400 Tube top 70 - 85 Hoodie 400 - 500 T-shirt 100 - 140 Jacket 230 - 400 Shirt 100 - 250 Coat 600 - 900 Dress 120 - 350 Wind-breaker 400 - 600 Evening dress 120 - 500 Autumn jacket 600 - 800 Wedding dress 800 - 2000 Winter jacket 800 - 1000 Business suit 800 - 950 Fur coat 3000 - 4000 Sports suit 650 - 750 Hat 60 - 120 Pants 300 - 400 Scarf 90 - 150 Leggings -

A Study on the Design and Composition of Victorian Women's Mantle

Journal of Fashion Business Vol. 14, No. 6, pp.188~203(2010) A Study on the Design and Composition of Victorian Women’s Mantle * Lee Sangrye ‧ Kim Hyejeong Professor, Dept. of Fashion Design, TongMyong University * Associate Professor, Dept. of Clothing Industry, Hankyong National University Abstract This study purposed to identify the design and composition characteristics of mantle through a historical review of its change and development focusing on women’s dress. This analysis was particularly focused on the Victorian age because the variety of mantle designs introduced and popularized was wider than ever since ancient times to the present. For this study, we collected historical literature on mantle from ancient times to the 19 th century and made comparative analysis of design and composition, and for the Victorian age we investigated also actual items from the period. During the early Victorian age when the crinoline style was popular, mantle was of A‐ line silhouette spreading downward from the shoulders and of around knee length. In the mid Victorian age from 1870 to 1889 when the bustle style was popular, the style of mantle was changed to be three‐ dimensional, exaggerating the rear side of the bustle skirt. In addition, with increase in women’s suburban activities, walking costume became popular and mantle reached its climax. With the diversification of design and composition in this period, the name of mantle became more specific and as a result, mantle, mantelet, dolman, paletot, etc. were used. The styles popular were: it looked like half-jacket and half-cape. Ornaments such as tassels, fur, braids, rosettes, tufts and fringe were attached to create luxurious effects. -

Proselect Store

Workwear T-SHIRT, High visibility SWEATER, High visibility PR01439, XS PR01445, XS PR01440, S PR01446, S PR01438, M PR01471, M PR01441, L PR01447, L PR01442, XL PR01448, XL PR01443, XXL PR01449, XXL PR01444, XXXL PR01450, XXXL VEST, High visibility JACKET, High visibility PR01458, L PR01402, XS PR01459, XL PR01403, S PR01404, M PR01405, L PR01406, XL PR01407, XXL PR01408, XXXL Workwear JACKET, High visibility JACKET, Fleece, High visibility PR01416, XS PR01431, XS PR01417, S PR01432, S PR01418, M PR01426, M PR01419, L PR01433, L PR01420, XL PR01434, XL PR01421, XXL PR01435, XXL PR01422, XXXL PR01436, XXXL JACKET, Operator jacket OVERALLS, High visibility PR01566, XS PR01473, XS (C42/C44) PR01567, S PR01474, S (C46/C48) PR01568, M PR01475, M (C50/C52) PR01569, L PR01476, L (C54/C56) PR01570, XL PR01477, XL (C58/C60) PR01571, XXL PR01478, XXL (C62/C64) PR01572, XXXL PR01479, XXXL (C66) Workwear OVERALLS, Lined, High visibility WORKSHOP OVERALLS PR01451, XS (C42/C44) PR01532, C48 PR01472, M (C50/C52) PR01533, C50 PR01453, L (C54/C56) PR01534, C52 PR01454, XL (C58/C60) PR01535, C54 PR01455, XXL (C62/C64) PR01536, C56 PR01456, XXXL (C66) PR01537, C58 WORKSHOP OVERALLS, Lined WORKWEAR SET, Jacket + Trousers PR01596, S PR01573, S + 48 PR01597, M PR01574, M + 50 PR01598, L PR01575, L + 52 PR01599, XL PR01576, XL + 54 PR01600, XXL PR01577, XXL + 56 PR01601, XXXL PR01578, XXXL + 58 PR01579, M + 48 PR01580, L + 50 PR01581, XL + 52 PR01582, XXL + 54 PR01583, XXXL + 56 Workwear * PR01423 TROUSERS, High visibility TROUSERS, High visibility PR01409, -

Key Details We Look for at Inspection

Key Details We Look for at Inspection Please not that these lists are not all inclusive but highlight areas that most often cause difficulty. Additional details are included on spec sheets for individual costumes. Boys’ Costumes Achterhoek: 1. Overall appearance of costume 2. Do you have the correct hat? This is the high one. Volendam is shorter. 3. The collar extends to the edge of the shirt and can be comfortably buttoned at the neck. 4. Ring on scarf and is visible above vest. If necessary use a gold safety pin to hold the ring in place. 5. Is the scarf on the inside of the vest, front and back? 6. Shirt buttons are in the center of the front band 7. The vest closes left over right. 8. The chain is in the 2nd buttonhole from the bottom 9. Welt pockets are made correctly and in the correct position. 10. Pants clear shoes. 11. Pants have a 6” hem Marken: 1.Overall appearance of costume 2.Red shirt underneath jacket 3.Red stitching on jacket placket 4.Closes as a boy (L. over R.) 5.Pants at mid-calf when pulled straight 6.Pants down 1” from waist Nord Holland Sunday: 1. Overall appearance of costume 2. Correct hat and scarf 3. Neck - can fit 1 finger 4. 2 dickies (one solid and one striped) 5. Jacket - collar flaps lay smooth 6. Buttonholes are horizontal 7. Jacket closes as a boy (left over right) 8. Cord, hook and eye at back of pants 9. Pants clear shoes 10.6 inch hem Noord Holland Work: 1. -

The War and Fashion

F a s h i o n , S o c i e t y , a n d t h e First World War i ii Fashion, Society, and the First World War International Perspectives E d i t e d b y M a u d e B a s s - K r u e g e r , H a y l e y E d w a r d s - D u j a r d i n , a n d S o p h i e K u r k d j i a n iii BLOOMSBURY VISUAL ARTS Bloomsbury Publishing Plc 50 Bedford Square, London, WC1B 3DP, UK 1385 Broadway, New York, NY 10018, USA 29 Earlsfort Terrace, Dublin 2, Ireland BLOOMSBURY, BLOOMSBURY VISUAL ARTS and the Diana logo are trademarks of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc First published in Great Britain 2021 Selection, editorial matter, Introduction © Maude Bass-Krueger, Hayley Edwards-Dujardin, and Sophie Kurkdjian, 2021 Individual chapters © their Authors, 2021 Maude Bass-Krueger, Hayley Edwards-Dujardin, and Sophie Kurkdjian have asserted their right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identifi ed as Editors of this work. For legal purposes the Acknowledgments on p. xiii constitute an extension of this copyright page. Cover design by Adriana Brioso Cover image: Two women wearing a Poiret military coat, c.1915. Postcard from authors’ personal collection. This work is published subject to a Creative Commons Attribution Non-commercial No Derivatives Licence. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher Bloomsbury Publishing Plc does not have any control over, or responsibility for, any third- party websites referred to or in this book. -

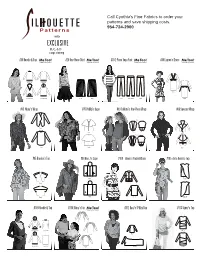

EXCLUSIVE B, C, & D Cup Sizing #10 Hoodie & Top #20 One‐Piece Skirt #30 2‐Piece Yoga Pant #40 Lauren’S Dress

Call Cynthia's Fine Fabrics to order your patterns and save shipping costs. 954-724-2900 with EXCLUSIVE B, C, & D cup sizing #10 Hoodie & Top #20 One‐Piece Skirt #30 2‐Piece Yoga Pant #40 Lauren’s Dress top front top back front hoodie front hoodie back front back front front elastic back back #65 Mary’s Wrap #75 Phillip’s Cape #83 Collette’s One‐Piece Wrap #85 Sweater Wrap front front back back #95 Brooke’s Top #96 Bee J’s Cape #100 Eileen’s Pocket Blouse #105 de la Renta’s Top front front back back #109 Hoodie & Top #110 Kiana’s Top #112 Kacy’s 5‐Way Top #113 Sunny’s Top Hoodie Front Top Frontn Back Fr nt Front Hoodie Back Top Back Back Front #114 BP’s Dual Zippered Top #115 Ann’s Top #116 Chanel’s Top #117 The Cut‐up Tee Front Back #125 Lee‐Ann’s Top #150 Dana’s Top #175 Valerie’s Top #185 Elie’s Top front front front front back back back back #195 Sweater Set #196 4‐Way Cardy #197 Kendosa’s Top #200 Kate’s Blouse Front Front front Front Back Back Back back #210 Jossiln’s Top #211 Nina’s Top #212 Kors Zippered Top #214 Lauren’s Shawl Collar Knit Wrap Top Front Front Back Back Front & Back #215 Nicky’s Favorite Top #216 Ronen’s Asymmetrical Top #219 Rachel’s Knit Top #221 Tahari’s Pullover Top #225 Sarah’s Blouse #231 Catherine‘s Button Sleeve Top Front front back Back #241 Gucci’s Knotted Top #250 Pam’s Blouse #300 Sharon’s Blouse #310 Marie’s Top front front front front front back back back #312 Georgio’s Top #313 Terri’s Shawl Collar V‐Neck #314 Abby’s Knit Top #315 BCBG’s Top front back #350 Stephanie’s Blouse #400 Traditional Blouse -

Clothing Terms from Around the World

Clothing terms from around the world A Afghan a blanket or shawl of coloured wool knitted or crocheted in strips or squares. Aglet or aiglet is the little plastic or metal cladding on the end of shoelaces that keeps the twine from unravelling. The word comes from the Latin word acus which means needle. In times past, aglets were usually made of metal though some were glass or stone. aiguillette aglet; specifically, a shoulder cord worn by designated military aides. A-line skirt a skirt with panels fitted at the waist and flaring out into a triangular shape. This skirt suits most body types. amice amice a liturgical vestment made of an oblong piece of cloth usually of white linen and worn about the neck and shoulders and partly under the alb. (By the way, if you do not know what an "alb" is, you can find it in this glossary...) alb a full-length white linen ecclesiastical vestment with long sleeves that is gathered at the waist with a cincture aloha shirt Hawaiian shirt angrakha a long robe with an asymmetrical opening in the chest area reaching down to the knees worn by males in India anklet a short sock reaching slightly above the ankle anorak parka anorak apron apron a garment of cloth, plastic, or leather tied around the waist and used to protect clothing or adorn a costume arctic a rubber overshoe reaching to the ankle or above armband a band usually worn around the upper part of a sleeve for identification or in mourning armlet a band, as of cloth or metal, worn around the upper arm armour defensive covering for the body, generally made of metal, used in combat. -

Singular/Plural Adjectives This/That/These/Those

067_SBSPLUS1_CH08.qxd 4/30/08 3:22 PM Page 67 Singular/Plural Adjectives This/That/These/Those • Clothing • Price Tags • Colors • Clothing Sizes • Shopping for Clothing • Clothing Ads • Money • Store Receipts VOCABULARY PREVIEW 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 1. shirt 6. jacket 11. pants 2. coat 7. suit 12. jeans 3. dress 8. tie 13. pajamas 4. skirt 9. belt 14. shoes 5. blouse 10. sweater 15. socks 67 068_075_SBSPLUS1_CH08.qxd 5/1/08 5:01 PM Page 68 Clothing 8 2 1 9 3 11 10 4 12 5 6 13 14 7 15 20 21 16 25 24 22 17 26 18 19 23 27 1. shirt 8. earring 15. hat 21. suit 2. tie 9. necklace 16. coat 22. watch 3. jacket 10. blouse 17. glove 23. umbrella 4. belt 11. bracelet 18. purse / 24. sweater 5. pants 12. skirt pocketbook 25. mitten 6. sock 13. briefcase 19. dress 26. jeans 7. shoe 14. stocking 20. glasses 27. boot 68 068_075_SBSPLUS1_CH08.qxd 5/1/08 5:01 PM Page 69 Shirts Are Over There SINGULAR/PLURAL* s z IZ a shirt – shirts a tie – ties a dress – dresses a coat – coats an umbrella – umbrellas a watch – watches a hat – hats a sweater – sweaters a blouse – blouses a belt – belts a necklace – necklaces A. Excuse me. A. Excuse me. A. Excuse me. I’m looking for a shirt. I’m looking for a tie. I’m looking for a dress. B. Shirts are over there. B. Ties are over there. -

AMUN Dress Code & the Representative Dance

American Model United Nations Conference Preparation Newsletter. 30 Sep 2019. American Model United Nations Conference Preparation Newsletter Information for Representatives! Dress Code and the 2019 Dance. Greetings from the AMUN Secretariat. Please forward this important information to your students. This newsletter covers information on our Conference Dress Code and Representative Dance, both of which we like to make certain students hear about as early as possible. AMUN’s Dress Code Like most Model UN Conferences, AMUN has a specific Dress Code for all conference attendees. For your convenience, the full text of this dress code is copied below. This information is also available in our Conference Handbook. Our dress code is meant to be inclusive while encouraging a professional atmosphere for deliberations. If you have any concerns about AMUN’s Dress Code or just need clarification please contact us at [email protected]. The appearance of AMUN participants provides the first impressions of their delegation to other representatives. Attention to proper appearance sets an expectation for professionalism and competence. In order to demonstrate respect to fellow representatives, Secretariat members and distinguished guests of the Conference, AMUN requires conservative Western business attire for all representatives and Secretariat during all formal sessions, including the final sessions on Tuesday. Western business attire is a business jacket or suit, dress slacks or skirt, dress shirt, appropriate hosiery or socks and dress shoes. Attire should follow the rule of being appropriate for visiting an embassy. Conservative accessories such as ties, scarves, and formal jewelry are traditional in business settings. Sweaters or leggings are too casual for Western business attire. -

Putting on and Taking Off a Jacket Information Sheet

SELF CARE DRESSING MYSELF PUTTING ON AND TAKING OFF A JACKET By one year your child should be able to help you as you dress them by pushing their arms and legs through items of clothing. By 2 years they should be able to remove an unfastened jacket. By 2 ½ years they can put on easy clothing such as a jacket or open front shirts without zipping/buttoning. By the age of 3 they should be able to assist with zipping and unzipping and separating the zip at the bottom of a jacket. Between the ages of 3-4 your child should be able to put their hands through both armholes and down the sleeves in front opening clothing (e.g. jacket). They should also be able to take the same item off completely. By 4 years old children should be able to get their clothes on and off independently but will not be able to manage fastenings (e.g. zips and buttons) for another year or two. HINTS AND TIPS It is much easier for your child to learn how to undress before dressing. Therefore practice taking off their jacket first. Start with a jacket that is a bit too big, loose-fitting clothing is easier to manage than tight fitting clothing. Let them practice putting on your jacket Children learn in different ways so you might need to vary your approach. There are a number of ways in which you can help: . Physically assist your child . Show your child . Tell your child You can use each of these ways individually or any combination depending on what suits your child. -

A Dictionary of Men's Wear Works by Mr Baker

LIBRARY v A Dictionary of Men's Wear Works by Mr Baker A Dictionary of Men's Wear (This present book) Cloth $2.50, Half Morocco $3.50 A Dictionary of Engraving A handy manual for those who buy or print pictures and printing plates made by the modern processes. Small, handy volume, uncut, illustrated, decorated boards, 75c A Dictionary of Advertising In preparation A Dictionary of Men's Wear Embracing all the terms (so far as could be gathered) used in the men's wear trades expressiv of raw and =; finisht products and of various stages and items of production; selling terms; trade and popular slang and cant terms; and many other things curious, pertinent and impertinent; with an appendix con- taining sundry useful tables; the uniforms of "ancient and honorable" independent military companies of the U. S.; charts of correct dress, livery, and so forth. By William Henry Baker Author of "A Dictionary of Engraving" "A good dictionary is truly very interesting reading in spite of the man who declared that such an one changed the subject too often." —S William Beck CLEVELAND WILLIAM HENRY BAKER 1908 Copyright 1908 By William Henry Baker Cleveland O LIBRARY of CONGRESS Two Copies NOV 24 I SOB Copyright tntry _ OL^SS^tfU XXc, No. Press of The Britton Printing Co Cleveland tf- ?^ Dedication Conforming to custom this unconventional book is Dedicated to those most likely to be benefitted, i. e., to The 15000 or so Retail Clothiers The 15000 or so Custom Tailors The 1200 or so Clothing Manufacturers The 5000 or so Woolen and Cotton Mills The 22000