Reconnecting Serbia Through Regional Cooperation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Circle of Scholars

Circle of Scholars 2021 Spring Online Circle Courses of Scholars Salve Regina University’s Circle of Scholars is a lifelong learning program for adults of all inclinations Online Seminar Catalog and avocations. We enlighten, challenge, and entertain. The student-instructor relationship is one of mutual respect and offers vibrant discussion on even the most controversial of global and national issues. We learn from each other with thoughtful, receptive minds. 360 degrees. Welcome to Salve Regina and enjoy the 2020 selection of fall seminars. Online registration begins on Wednesday, February 3, 2021 at noon www.salve.edu/circleofscholars Seminars are filled on a first-come, first-served basis. Please register online using your six-digit Circle of Scholars identification number (COSID). As in the past, you will receive confirmation of your credit card payment when you complete the registration process. For each seminar you register for, you will receive a Zoom email invitation to join the seminar 1-3 days before the start date. If you need assistance or have questions, please contact our office at (401) 341-2120 or email [email protected]. Important Program Adjustments for Spring 2021 • Most online seminars will offer 1.5 hour sessions. • Online class fees begin at $15 for one session and range to $85 for 8 sessions. • The 2019-2020 annual membership was extended from July 2019 - December 2020 due to COVID- 19. Membership renewal is for • Zoom is our online platform. If you do not have a Zoom account already, please visit the Zoom website to establish a free account at https://zoom.us. -

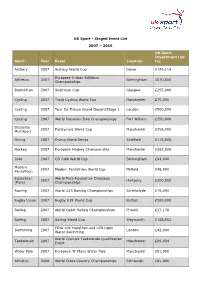

Staged Event List 2007 – 2019 Sport Year Event Location UK

UK Sport - Staged Event List 2007 – 2019 UK Sport Investment (up Sport Year Event Location to) Archery 2007 Archery World Cup Dover £199,114 European Indoor Athletics Athletics 2007 Birmingham £570,000 Championships Badminton 2007 Sudirman Cup Glasgow £255,000 Cycling 2007 Track Cycling World Cup Manchester £75,000 Cycling 2007 Tour De France Grand Depart/Stage 1 London £500,000 Cycling 2007 World Mountain Bike Championships Fort William £250,000 Disability 2007 Paralympic World Cup Manchester £358,000 Multisport Diving 2007 Diving World Series Sheffield £115,000 Hockey 2007 European Hockey Championship Manchester £262,000 Judo 2007 GB Judo World Cup Birmingham £94,000 Modern 2007 Modern Pentathlon World Cup Milfield £48,000 Pentathlon Equestrian World Para-Equestrian Dressage 2007 Hartpury £200,000 (Para) Championships Rowing 2007 World U23 Rowing Championships Strathclyde £75,000 Rugby Union 2007 Rugby U19 World Cup Belfast £289,000 Sailing 2007 World Cadet Sailing Championships Phwelli £37,178 Sailing 2007 Sailing World Cup Weymouth £168,962 FINA 10K Marathon and LEN Open Swimming 2007 London £42,000 Water Swimming World Olympic Taekwondo Qualification Taekwondo 2007 Manchester £99,034 Event Water Polo 2007 European 'B' Mens Water Polo Manchester £81,000 Athletics 2008 World Cross Country Championships Edinburgh £81,000 Boxing 2008 European Boxing Championships Liverpool £181,038 Cycling 2008 World Track Cycling Championships Manchester £275,000 Cycling 2008 Track Cycling World Cup Manchester £111,000 Disability 2008 Paralympic World -

2021 Fina Clinics for Coaches & Officials

2021 FINA CLINICS FOR COACHES & OFFICIALS Guidelines 2021 FINA CLINICS FOR COACHES & OFFICIALS Guidelines 1 2021 FINA CLINICS FOR COACHES & OFFICIALS Guidelines INDEX Introduction How to host/register • Overview 3 • How to host a FINA Clinic 9 • Objective 3 • How to register in a FINA Clinic 9 Clinic description and format Clinic organisation • Description 4 • Clinic details 10 • Course format 4 • Material or artwork produced 10 • Clinic location 5 • Teaching modalities 5 Financial conditions • Clinic content 5 • Regulations for FINA Clinics 11 • Certificates 7 • Economical support 11 • Clinic fees 7 • FINA Online Clinic 13 Bidding procedure • Reimbursement procedure 14 • Invoicing guidelines 14 • Application procedure 8 • Analysis and approval 8 2 2021 FINA CLINICS FOR COACHES & OFFICIALS Guidelines 2021 FINA CLINICS FOR COACHES AND OFFICIALS Introduction Overview FINA strongly believes in the importance of having a globally-respected workforce of coaches and swimming officials with an established and consistent curriculum, as a key factor for the athlete development and the correct appliance of the FINA officiating rules. As part of the FINA Development Programme, FINA is currently running clinics to train coaches in each of the six aquatic disciplines: swimming, open water swimming, artistic swimming, water polo, diving and high diving and to train officials in swimming. Both training programmes, respectively conducted by highly experienced coaches and officials appointed by FINA, are designed to educate and train coaches and swimming officials around the world. With this initiative, FINA offers to its 209 affiliated national federations the opportunity to successfully develop the aquatic sports in their countries. Objective The FINA Clinics for Coaches and FINA Swimming Clinics for Officials are intended to provide basic training for participants of all levels through courses led by an expert nominated by FINA. -

Sports Rights Catalogue 2017/2018

OPERATING EUROVISION AND EURORADIO SPORTS RIGHTS CATALOGUE 2017/2018 1 ABOUT US The EBU is the world’s foremost alliance of The core of our operation is the acquisition Flexible and business orientated are traits public service media organizations, with and distribution of media rights. We work with which perfectly complement the EBU’s well members in 56 countries in Europe and more than 30 federations on a continually established and highly effective distribution beyond. renewable sports rights portfolio consisting of model on a European and Worldwide basis. football, athletics, cycling, skiing, swimming The EBU’s mission is to safeguard the interests and many more. We are proud to collaborate Smart business thinking and commitment to of public service media and to promote their with elite federations such as FIFA*, UEFA*, innovation means the EBU is a key component indispensable contribution to modern society. IAAF, EAA, UCI, FINA, LEN, FIS, IPC, to name at all stages of the broadcast value chain. The a few. EBU is the ideal one-stop-shop partner for the Under the alias, EUROVISION, the EBU broadcast community. produces and distributes top-quality live In 2011, EBU created the Sales Unit to enhance sports and news, as well as entertainment, its competitiveness in an ever-evolving and * EBU Football contracts with FIFA and UEFA are culture and music content. Through extremely challenging industry. The Unit directly handled by the EBU Football Unit. EUROVISION, the EBU provides broadcasters handles the commercial distribution of sports with on-site facilities and services for major rights in EBU’s portfolio in not only European world events in news, sport and culture. -

USMS Liaison & Special Assignments Reports

USMS SPECIAL ASSIGNMENTS & LIAISON REPORTS CONTROLLER – Margaret Bayless I officially commenced as USMS Controller on March 1, 2004. During February, I traveled to Washington DC for a handover weekend with Cathy Pennington. Doug Church, Treasurer, also joined us for a good portion of the weekend. Cathy and I had a follow-up meeting in late May. As a result of these meetings, I prepared a Controller’s Manual to help memorialize in detail many of the tasks associated with the Controller position. During the time I have been Controller, the 2003 books have been closed, and have been submitted to the independent auditors for their review. The auditor’s report will be completed in time to be included in the Convention information package. The 2003 tax return is on extension, although it is mostly completed, and awaiting confirmation of final financial results from the auditors prior to filing. The 2003 full-year financial statements and the monthly financial statements for each of January – May 2004 have been submitted with commentary to the EC and Finance Committee. The non-year-end monthly financial statements are generally issued in the third or fourth week of the following month, after receipt of the final monthly registration report from the National Office. The 2003 full-year and the 2004 first quarter reports of expenses have been submitted to the respective committee heads and officers. The non-year-end quarterly reports of expenses are generally distributed via email by the 15th of the month following each quarter-end. Checks are prepared and mailed every week; each Friday morning, I submit a check request report to Doug, who prepares and mails the checks. -

Record Application for European Masters Records

RECORD APPLICATION FOR EUROPEAN MASTERS RECORDS European Masters Records are recognised for men and women in 50 metre and 25 metre courses in accordance with LEN General Event Rules E 5. In relays all members of a team must be from the same club. European Masters Records can only be established in Masters meets sanctioned by Members of LEN or FINA. The length of each lane of the course must be certified by a surveyor or other qualified official appointed or approved by the National Swimming Federation. European Masters Records will be accepted only when times are reported by Automatic Officiating Equipment, or Semi Automatic Officiating Equipment, or Manual Timing taken by three appointed timekeepers. The timing shall be registered by 1/100 of a second. Times which are equal to 1/100 of a second will be recognised as equal records and swimmers achieving these equal times will be joint holders. Only the time of the winner of a race may be submitted for a European Masters Record. In the event of a tie in a record setting race, each swimmer who tied shall be considered a winner. The first swimmer in a relay may apply for a European Masters Record. Should the first swimmer in a relay team complete his distance in a record time in accordance with the provisions of this subsection, his performance shall not be nullified by any subsequent disqualification of his relay team for violation occurring after his distance has been completed. Applications for European Masters Records must be made on a LEN Official Application Form by the responsible authority of the organising or management committee of the competition and signed by an authorised representative of the relevant Swimming Federation. -

Download More Information

SWIM WALES NOFIO CYMRU ANNUAL REPORT & ACCOUNTS 2019 – 2020 OUR VISION Aquatics for everyone for life. OUR MISSION A world leading NGB delivering excellence, inspiring our nation to enjoy, participate, learn and compete in Welsh Aquatics. 04 // CHAIRMAN REPORT 05 // CHIEF EXECUTIVE REPORT 06 // AQUATIC DEVELOPMENT 08 // BUSINESS DEVELOPMENT 09 // ELITE & PERFORMANCE 12 // EQUALITY 13 // GOVERNANCE 16 // ACCOUNTS 14 // SAFEGUARDING CHAIRMAN REPORT CHAIRMAN REPORT, SWIM WALES ANNUAL REPORT Y/E 31ST MARCH 2020 Although the last six months has certainly proved to be a turbulent period for all of us, I am delighted to testify that the full year prior to lockdown at the end of March 2020, proved a very significant year for Swim Wales. Considerable steps were made towards achieving our vision of “Aquatics for Everyone for Life”. We not only delivered outstanding performances at local, regional, national, and international events but sustained the focus on our core governance policies including, financial stability, resilience, equality, inclusivity, welfare and safeguarding. Whilst our clubs and members are the beating heart of their own communities, as the responsible NGB, they also remain at the very centre of why we do what we do. This means we are committed to absolute inclusivity and flexibility in our approach to the advancement of aquatics, and in all our discussions with members, volunteers, clubs, and partners. Over 17% of the population in Wales, some 400,000 adults and 100,000 children, were engaged in swimming, learn-to-swim, or aquatic activity, at least once a week pre-lock down. However, one of our greatest strengths is the huge breadth of our aquatic activities, from learn-to-swim right up to our elite performance champions. -

Home Advantage in European International Soccer: Which Dimension of Distance Matters?

Vol. 13, 2019-50 | December 09, 2019 | http://dx.doi.org/10.5018/economics-ejournal.ja.2019-50 Home advantage in European international soccer: which dimension of distance matters? Nils Van Damme and Stijn Baert Abstract The authors investigate whether the home advantage in soccer differs by various dimensions of distance between the (regions of the) home and away teams: geographical distance, climatic differences, cultural distance, and disparities in economic prosperity. To this end, the authors analyse 2,012 recent matches played in the UEFA Champions League and UEFA Europa League by means of several regression models. They find that when the home team plays at a higher altitude, they benefit substantially more from their home advantage. Every 100 meters of altitude difference is associated with an increase in expected probability to win the match, as the home team, by 1.1 percentage points. The other dimensions of distance are not significantly associated with a higher or lower home advantage. By contrast, the authors find that the home advantage in soccer is more outspoken when the number of spectators is higher and when the home team is substantially stronger than the away team. JEL L83 J44 Z00 Keywords Soccer; home advantage; cultural distance; UEFA Champions League; UEFA Europa League Authors Nils Van Damme, Ghent University, Ghent, Belgium Stijn Baert, Ghent University, Ghent, Belgium; Research Foundation – Flanders, Brussels, Belgium; University of Antwerp, Antwerp, Belgium; Université catholique de Louvain, Louvain-la-neuve, Belgium; Institute of Labor Economics (IZA), Bonn, Germany; Global Labor Office (GLO), Stanford, USA; IMISCOE, Rotterdam, Netherlands, [email protected] Citation Nils Van Damme and Stijn Baert (2019). -

The Annual Report and Accounts 2019 2 British Swimming Annual Report and Accounts 2019 British Swimming Annual Report | Company Information 3

The Annual Report and accounts 2019 2 British Swimming Annual Report and Accounts 2019 British Swimming Annual Report | Company Information 3 Company Contents Information For the year ended 31 March 2018 03 company Information CHAIRMAN REGISTERED OFFICE 04 Chairman’s Report Edward Maurice Watkins CBE British Swimming Pavilion 3 05 CEO’S report DIRECTORS Sportpark 06 Monthly Highlights 3 Oakwood Drive Keith David Ashton Loughborough 08 World Championships Jack Richard Buckner LE11 3QF 10 World Para Swimming Championships David Robert Carry Bankers 11 Excellence - Swimming Urvashi Dilip Dattani Lloyds Bank 15 Excellence - Diving Graham Ian Edmunds 37/38 High Street 19 Excellence - para-Swimming Loughborough Jane Nickerson Leicestershire 22 NON Funded sports update Fergus Gerard Feeney LE11 2QG 23 Corporate UPDATE Alexandra Joanna Kelham Coutts & Co. 24 International relations 440 Strand Peter Jeremy Littlewood London 26 governance Statement Graeme Robertson Marchbank WC2R 0QS 28 Major events Adele Stach-Kevitz AUDITOR 30 Marketing and communications COMPANY SECRETARY Mazars LLP 31 finances ParkView House 38 Acknowledgements Ashley Cox 58 The Ropewalk Nottingham COMPANY REGISTRATION NUMBER NG15DW 4092510 Front Cover Images: FINA Champions Swim Series 2019 – Imogen Clark. FINA World Championships 2019 – Thomas Daley. World Para-swimming Allianz Championships 2019 – Tully Kearney. 4 British Swimming Annual Report and Accounts 2019 British Swimming Annual Report | CEO's Report 5 Chairman’s CEO's Report Report edward MAURICE WATKINS CBE Jack Richard Buckner This was yet another noteworthy year for British Swimming with was clarified since when British Athletes have been involved in There was a time when the year before the Olympic and We are now moving forward with a focus on the Tokyo Olympics the 18th FINA World Aquatic Championships in Gwangju South both the inaugural FINA Champions Series and will be available Paralympic games was a slightly quieter year in the hectic world and Paralympics. -

Economic Crisis and Organized Crime in Lithuania

ISSN 1392–6195 (print) ISSN 2029–2058 (online) JURISPRUDENCIJA JURISPRUDENCE 2011, 18(1), p. 303–326. ECONOMIC CRISIS AND ORGANIZED CRIME IN LITHUANIA Aurelijus Gutauskas Mykolas Romeris University, Faculty of Law, Department of Criminal Law and Criminology Ateities 20, LT-08303 Vilnius, Lithuania Telephone (+370 5) 2714 584 E-mail [email protected] Received 16 February, 2011; accepted 24 March, 2011 Abstract. Tendencies of organized crime in the context of economical crisis are dealt in the article. The author shows his own position about the economical crisis and how it inf- luenced organized crime in Lithuania. The reasons of economical crisis, characteristics and peculiarities of crimes of organized groups, which operate in Lithuania, are discussed in the article. The author reveals specific features, which enable to evaluate the real influence of organized groups to the economical state of Lithuania. Keywords: organized crime, economic crisis, tendencies of the evaluation of organized crime activity, criminal activity. Jurisprudencija/Jurisprudence ISSN 1392–6195 (print), ISSN 2029–2058 (online) Mykolo Romerio universitetas, 2011 http://www.mruni.eu/lt/mokslo_darbai/jurisprudencija/ Mykolas Romeris University, 2011 http://www.mruni.eu/en/mokslo_darbai/jurisprudencija/ 304 Aurelijus Gutauskas. Economic Crisis and Organized Crime in Lithuania 1. Social Consequences of Economic Downturn in Lithuania: Increase in the Crime Rate Economic crisis usually occur as a result of sudden, unanticipated shocks (e.g., the shock that arises from large capital outflows), and they lead to a sharp decline in the output and often to a substantial increase in prices.1 Economic crises affect communi- ties and households in a number of ways. -

Organization of Fina

ORGANIZATION OF FINA FINA – founded on 19 July 1908 at the Manchester Hotel, London (GBR) Founding Federations: Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Great Britain, Hungary and Sweden Primary Objectives: Establish competition rules for Swimming, Diving, High Diving, Water Polo, Synchronized Swimming, and Open Water Swimming Conduct international competitions, including the Olympic Games Promote and encourage the development of the sport Organization of FINA: General Congress Technical Congresses FINA Bureau Technical Committees Specialized Committees Commissions (discretionary) Congresses: General Congress is highest authority within FINA Technical Congresses Diving Synchronized Open Water Swimming & Water Polo Masters Swimming Swimming High Diving •President 24 Bureau •Vice Presidents (5) Members •Honorary Secretary •Honorary Treasurer (with vote) •Members (15) •Honorary Life President Non-Voting •Honorary Members Members •FINA Executive Director •Chairman of the Athletes Committee FINA Technical Committees: Swimming (1908) Diving (1928) – High Diving (2013) Water Polo (1928) Synchronized Swimming (1956) Sports Medicine (1968) Masters (1986) Open Water (1992) FINA Specialised Committees: Sports Medicine Committee Athletes Committee Coaches Committee Media Committee Doping Control Review Board Legal Committee Swimwear Approval Committee Awards Committee Development Committee Facilities Committee National Federations Relations Committee Legal Committee FINA Judicial Panels: Doping Panel Disciplinary -

Corruption in Serbia: BRIBERY AS EXPERIENCED by the POPULATION

Vienna International Centre, PO Box 500, 1400 Vienna, Austria Tel.: (+43-1) 26060-0, Fax: (+43-1) 26060-5866, www.unodc.org CORRUPTION IN SERBIA BRIBERY AS EXPERIENCED BY THE POPULATION BRIBERY Corruption in Serbia: BRIBERY AS EXPERIENCED BY THE POPULATION Co-fi nanced by the European Commission UNITED NATIONS OFFICE ON DRUGS AND CRIME Vienna CORRUPTION IN SERBIA: BRIBERY AS EXPERIENCED BY THE POPULATION Copyright © 2011, United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime Acknowledgments This report was prepared by UNODC Statistics and Surveys Section (SASS) and Statistical Office of the Republic of Serbia: Field research and data analysis: Dragan Vukmirovic Slavko Kapuran Jelena Budimir Vladimir Sutic Dragana Djokovic Papic Tijana Milojevic Research supervision and report preparation: Enrico Bisogno (SASS) Felix Reiterer (SASS) Michael Jandl (SASS) Serena Favarin (SASS) Philip Davis (SASS) Design and layout: Suzanne Kunnen (STAS) Drafting and editing: Jonathan Gibbons Supervision: Sandeep Chawla (Director, Division of Policy Analysis and Public Affairs) Angela Me (Chief, SASS) The precious contribution of Milva Ekonomi for the development of survey methodology is gratefully acknowledged. This survey was conducted and this report prepared with the financial support of the European Commission and the Government of Norway. Sincere thanks are expressed to Roberta Cortese (European Commission) for her continued support. Disclaimers This report has not been formally edited. The contents of this publication do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of UNODC or contributory organizations and neither do they imply any endorsement. The designations employed and the presentation of material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion on the part of UNODC concerning the legal status of any country, territory or city or its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries.