Whose Land, Whose Water

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Village & Townwise Primary Census Abstract, Gurgaon, Part XIII a & B

CENSUS OF INDIA 1981 SBRIES-6 HARYANA DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK- PARTS XIII A & B VILLAGE & TOWN DIRECTORY VILLAGE & TOWNWISE PRIMARY CENSUS ABSTRACT GURGAON DISTRICT o. P. BHARADWAJ OF THE INDIAN ADMTNISTRATIVE SERVICE Director of Census Operations Haryana published by the Government of Haryana 1983 The name GUT9(uJn !"uppo$ed :c be u (:()t1V Upt form oj G1.t1'UgTom is traced to Daronachary«, the teacheT of "the Kuru princes-the Pandavas and }~auTavas. In the motif, Da1fOnIJi.CM1·rya i..s helping the little princes in ge-ttiHg their ball out oj the wif'lZ by c"r-eating a st11.ny oj a1"'7'01.tI$o He was engaged for training the-rn ·i.n archery by theiT grandfather Bhisma when the depicted incident t.oo,.:;· T(i'"(.qled to him CENSUS OF INDIA-1981 A-CENTRAL GOVERNMENT PUBLICATIONS 'fhe publications relating to Haryana bear Series No. 6 and will he published as follows: PartI~A Administration Report-Enumeration (for official use only) Part I-B Administration Report-Tabulation (for official use only) Part II-A General Popul[\tion Tables ') ~ combined Part Il-B primary Censu') Abstract J Part III General Economic Tables . Part IV Social and Cultural Tables / part V Migration Tables Part VI Fertility Tables Part VII Tables on Houses an.d Disabled Population Part ViiI Household Tables Part IX Special Tables on Scheduled Castes part X-A Town Directory Part X-B Survey Reports on selected towns P4rt x-C Survey Reports on selected villages Part XI Ethnographic notes and special studies on Scheduled Castes Part XII Census Atlas B-HARYrANA GOVERNMENT PUBLJCATIONS Parts XIII-A & B . -

ORIENTAL BANK of COMMERCE.Pdf

STATE DISTRICT BRANCH ADDRESS CENTRE IFSC CONTACT1 CONTACT2 CONTACT3 MICR_CODE D NO 10-86, MAIN RD, OPP MUNICIPAL CORPORATION, ANDHRA MANCHERIAL, MANCHERIY 011- PRADESH ADILABAD MANCHERIAL ANDHRA PRADESH AL ORBC0101378 23318423 12-2-990, PLOT NO 66, MAIN ROAD, ANDHRA SAINAGAR, ANANTAPU 040- PRADESH ANANTAPUR ANANTHAPUR ANANTHAPUR R ORBC0101566 23147010 D.NO.383,VELLORE ROAD, ANDHRA GRAMSPET,CHITTOO 970122618 PRADESH CHITTOOR CHITTOOR R-517002 CHITTOOR ORBC0101957 5 EC ANDHRA TIRUMALA,TIRU TTD SHOPPING 0877- PRADESH CHITTOOR PATI COMPLEXTIRUMALA TIRUPATI ORBC0105205 2270340 P.M.R. PLAZA, MOSQUE ROADNEAR MUNICIPAL ANDHRA OFFICETIRUPATI, 0877- PRADESH CHITTOOR TIRUPATI A.P.517501 TIRUPATI ORBC0100909 2222088 A P TOURISM HOTEL COMPOUND, OPP S P 08562- ANDHRA BUNGLOW,CUDDAPA 255525/255 PRADESH CUDDAPAH CUDDAPAH H,PIN - 516001 CUDDAPAH ORBC0101370 535 D.NO 3-2-1, KUCHI MANCHI AMALAPURAM, AGRAHARAM, BANK ANDHRA EAST DIST:EAST STREET, DISTT: AMALAPUR 08856- PRADESH GODAVARI GODAVARI EAST GODAVARI , AM ORBC0101425 230899 25-6-40, GROUND FLOORGANJAMVARI STREET, KAKINADADIST. ANDHRA EAST EAST GODAVARI, 0884- PRADESH GODAVARI KAKINADA A.P.533001 KAKINADA ORBC0100816 2376551 H.NO.13-1-51 ANDHRA EAST GROUND FLOOR PRADESH GODAVARI KAKINADA MAIN ROAD 533 001 KAKINADA ORBC0101112 5-8-9,5-8-9/1,MAIN ROAD, BESIDE VANI MAHAL, MANDAPETA, DISTT. ANDHRA EAST EAST GODAVARI, PIN MANDAPET 0855- PRADESH GODAVARI MANDAPETA - 533308 A ORBC0101598 232900 8-2A-121-122, DR. M. GANGAIAHSHOPPIN G COMPLEX, MAIN ANDHRA EAST ROADRAJAHMUNDR RAJAHMUN 0883- PRADESH GODAVARI -

Gurgaon-Manesar Urban Complex

Trans.Inst.Indian Geographers ISSN 0970-9851 Gurgaon-Manesar Urban Complex Sheetal Sharma and Anjan Sen, Delhi Abstract Central National Capital Region/Central NCR is one of the four policy zones of National Capital Region (NCR) as per its Regional Plan 2021. Central NCR is an ‘inter-state functional region’ pivoted upon the National Capital Territory of Delhi (NCT of Delhi), and is successor to the Delhi Metropolitan Area (DMA). It comprises six urban complexes or zones, four in Haryana (Sonipat-Kundli, Bahadurgarh, Gurgaon-Manesar, and Faridabad- Ballabhgarh) and two in Uttar Pradesh (NOIDA and Ghaziabad-Loni). The study presents the levels of development in terms of urban influence on settlements, and functional hierarchy of settlements, in the Gurgaon-Manesar urban complex of Central NCR. The present study is a micro-level study, where all 120 settlements (both urban and rural) comprising Gurgaon- Manesar urban complex of Central NCR, form part of the study. The study is based upon secondary data sources, available from Census of India; at settlement level (both town and village) for the decennial years 1981, 1991 and 2001. The paper determines the level of urban influence and functional hierarchy in each settlement, at these three points of time, and analyses the changes occurring among them. The study reveals the occurrence of intra- regional differentials in demographic characteristics and infrastructural facilities. The study also emphasis on issues of development in rural settlements and growth centers, in the emerging urban complex within Central NCR. The work evaluates the role of Haryana Urban Development Authority in the current planning processes of development and formulates suitable indicators for development. -

DBA-VOTING-LIST-2018.Pdf

Sl.No. Name Address Bar Council Bar No. Phone Phone T.U.P. H.No-322/14, Jacubpura, 1 A.L.Sahni P/1007/1983 2 2321473 9313401837 Gurgaon H.No-763-A, Ist Floor, 2 Aakash Aggarwal Block-H, Palam Vihar, P/695/1999 4 9350840785 9910991353 Gurgaon. V.P.O. Dhunela, Post 3 Aakil Ali P/3239/2014 4051 9050300395 9813313823 Office Sohna, Gurgaon H.No-249,Sector-17-A 4 Aarti Bhalla P/2016/2015 4246 9350320004 Gurgaon. H.No-224/7, H.B. 5 Aarti Hans Colony, Sec-7 Ext, P/1398/2011 3061 9910383914 Gurgaon Vill- Udaka, PO-Sohna, 6 Aazad P/3601/2009 2544 9711115701 Distt- Gurgaon Gandhi Nagar Ward No. 7 Abdul Hamid 8 Opp Mewat Model P/778/1994 4054 8860481185 School Tauru. Vill-Rewasan, Teh -Nuh, 8 Abdul Rehman P/95/1998 6 9416256151 9813039030 Distt-Gurgaon PWO Housing Complex, B-2/301, Sector 43, 9 Abha Sinha Sushant Lok-I, Gurgaon P/1800/1999 4751 9871957449 At(P) C-6/6360, Vasant Kunj, New Delhi H.No-645/20, Gali No-6, 10 Abhai singh Yadav P/514/1977 3100 9250171144 Shivji Park, Gurgaon Abhey singh H.No.1434, Sec-15, Part- 0124- 11 P/1132/2001 8 9811198319 Dahima II, Gurgaon. 6568432 Resi-Vill-Dhanwa Pur, Abhey Singh 12 Po-Daulta Bad, Distt- P/857/1995 9 9811934070 Dahiya Gurgaon H.No-209/4, Subhash 13 Abhey Singla P/420/2007 2008 9999499932 9811779952 Nagar, Gur. H.No. 225, sector 15, 14 Abhijeet Gupta P/4107/2016 4757 9654010101 Part-I, Gurgaon. -

Rupesh Kumar Gupta Sudesh Nangia

Population Explosion and Land Use Changes in Gurgaon City Region-A Satellite of Delhi Metropolis Rupesh Kumar Gupta Sudesh Nangia, Key Words: L and transformation, Urban encroachment, Built-up land, Multi-Temporal, Spatio-Tempo., RS, GIS Abstract In developing countries, rapid population growth has meant a decline in the arable land per capita and switch over to industrial, residential, commercial land uses. In 1961, for example, developing countries as a whole had an average of about one-half of a hectare of arable land per person; by 1992 the share had fallen to less than one-fifth of an hectare. If current trends in population growth continue, it is estimated that by 2050,the amount of arable land will be just over one-tenth hectare per person. This paper is the case study of a town named Gurgaon in the urban shadow zone of capital city of India i.e. Delhi, in terms of its population explosion and land use changes. The population of Gurgaon has grown from 57 thousand in 1971 to 1.74 lakh in 2001. The growth rate has also indicated an increasing trend. In addition, the pressure of continuously growing metropolitan city is also changing the structure of the town and its surrounding neighborhood. In this paper, the authors have tried to investigate the changes in land use pattern of Gurgaon region that have occurred over the past few decades, and have tried to associate them with population growth, urbanization and industrialization of the countryside. For this purpose, multi-temporal RS and GIS data sets are used. -

Water Energy Food Nexus in Urban Ecosystem

Final Report Water Energy Food Nexus in Urban Ecosystem: An assessment of challenges and opportunities for adaptation in urban areas Report on completion of Project A joint study by The Energy & Resources Institute and India Water Partnership Water Energy Food Nexus in Urban Ecosystem © The Energy and Resources Institute 2015 Suggested format for citation T E R I. 2015 Water Energy Food Nexus in Urban Ecosystem New Delhi: The Energy and Resources Institute. For more information Dr. Shresth Tayal Fellow & Area Convenor Water Resources Division T E R I Tel. 2468 2100 or 2468 2111 Darbari Seth Block E-mail [email protected] IHC Complex, Lodhi Road Fax 2468 2144 or 2468 2145 New Delhi – 110 003 Web www.teriin.org India India +91 • Delhi (0)11 ii Water Energy Food Nexus in Urban Ecosystem Table of contents TABLE OF CONTENTS ................................................................................................................... III LIST OF TABLES .............................................................................................................................. V LIST OF FIGURES .......................................................................................................................... VI EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................................... 1 1. WATER ENERGY FOOD NEXUS IN URBAN ECOSYSTEM ...................................................... 3 Introduction ............................................................................................................................ -

Administrative Map

Bajghera(61) Badhosra ´ 0.4 0.2 0 0.4 km Raghu Pur Administrative Map Nanak Heri Gram Panchayat : Babupur Block : Gurgaon District : Gurgaon State : Haryana Babupur(60) Choma(62) Dharampur(59) Legend GP Boundary Village Boundary World Street Map Data Source : SOI,NIC,Esri Pawala Khasrupur(57) Mohmadheri(58) Map composed by : RS & GIS Div, NIC Daultabad(53) Sources: Esri, HERE, DeLorme, USGS, Intermap, increment P Corp., NRCAN, Esri Japan, METI, Esri China (Hong Kong), Esri (Thailand), TomTom, MapmyIndia, © OpenStreetMap contributors, and the GIS User Community Gurgaon (Rural) (CT) Central West 4 2 0 4 km Ne´w Delhi South West No. Of Households Bahadurgarh Block : Gurgaon Babupur Jhajjar District : Gurgaon South State : Haryana Gurgaon Legend Block Boundary Farrukhnagar GP Boundary Village Boundary Urban_area Village Boundary(No. Of Households) Data Not Available Faridabad 1 - 500 501 - 1000 1001 - 5074 Sohna Ballabgarh Pataudi Data Source : SOI,NIC,Esri Taoru Map composed by : RS & GIS Div, NIC Palwal Rewari Nuh Central West 4 2 0 4 km Ne´w Delhi South West Total Persons Bahadurgarh Block : Gurgaon Babupur Jhajjar District : Gurgaon South State : Haryana Gurgaon Legend Block Boundary Farrukhnagar GP Boundary Village Boundary Urban_area Village Boundary(Total Persons) Data Not Available Faridabad 1 - 1500 1501 - 3000 3001 - 23448 Sohna Ballabgarh Pataudi Data Source : SOI,NIC,Esri Taoru Map composed by : RS & GIS Div, NIC Palwal Rewari Nuh Central West 4 2 0 4 km Ne´w Delhi South West Total Population Male Bahadurgarh Block : Gurgaon Babupur -

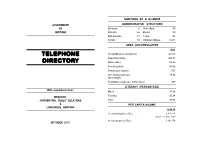

Telephone Directory

HARYANA AT A GLANCE GOVERNMENT ADMINISTRATIVE STRUCTURE OF Divisions 6 Sub-tehsils 49 HARYANA Districts 22 Blocks 140 Sub-divisions 71 Towns 154 Tehsils 93 Inhabited villages 6,841 AREA AND POPULATION 2011 TELEPHONE Geographical area (sq.kms.) 44,212 Population (lakh) 253.51 DIRECTORY Males (lakh) 134.95 Females (lakh) 118.56 Density (per sq.km.) 573 Decennial growth-rate 19.90 (percentage) Sex Ratio (females per 1000 males) 879 LITERACY (PERCENTAGE) With compliments from : Males 84.06 Females 65.94 DIRECTOR , INFORMATION, PUBLIC RELATIONS Total 75.55 & PER CAPITA INCOME LANGUAGES, HARYANA 2015-16 At constant prices (Rs.) 1,43,211 (at 2011-12 base year) At current prices (Rs.) 1,80,174 (OCTOBER 2017) PERSONAL MEMORANDA Name............................................................................................................................. Designation..................................................................................................... Tel. Off. ...............................................Res. ..................................................... Mobile ................................................ Fax .................................................... Any change as and when occurs e-mail ................................................................................................................ may be intimated to Add. Off. ....................................................................................................... The Deputy Director (Production) Information, Public Relations & Resi. .............................................................................................................. -

16Th September 2019 To, Nodal Officer Cum Secretary, Justice (Retd.) R.M. Lodha Committee (In the Matter of PACL Ltd.) SEBI

SLF 16th September 2019 To, Nodal Officer cum Secretary, Justice (Retd.) R.M. Lodha Committee (In the matter of PACL Ltd.) SEBI, Mumbai Sir, Kindly refer to your Public Notice dated 19th Aug 2019 for submission of EoI for PACL properties. We are pleased to submit our Expression of Interest (EoI) to participate in the sale / auction process for the PACL properties – North Zone. Please find attached the copy of our EoI. Thanking You For SLF M. WASIM Authorised Signatory SLF REALTY: S.414, GREATER KAILASH, NEW DELHI -48 OFFER FOR NORTH ZONE PROPERTIES Rs. Cr. North Zone Offer Price Delhi Rural 421.57 GuatamBudh Nagar Rural 106.93 Gurgaon Rural 167.62 SAS Nagar Rural 274.97 LONI Rural 38.61 Mussorie 4.47 North Zone - Cities 111.00 Total 1,125.17 1 Properties shortlisted are detailed in subquent pages 2 Offer is non-binding and subject to legal due diligence with respect of Title, Posession, Litigation, Encumberances, Records of Rights, Transferability, Claimsm, Demarcation, Boundary Fixation, Partition, Sub-Division, Acquisition etc. 3 The proposal includes properties mentioned as not for sale as the updated status of such properties in not available post objections received by Lodha Committee 4 The offer is based on limited information available on paclauction.com and the veracity of information has not been confirmed at this stage while preparing the EoI and the offer shall be revised post due diligence findings MR No AREA STATE DISTRICT TEHSIL VILLAGE 2065-14 7.15 Delhi Delhi Punjabi Bagh Bakkarwala 2076-14 5.32 Delhi Delhi Punjabi Bagh -

Town Survey Report Gurgaon, Part-X-B, Series-6, Haryana

CENSUS OF IND,IA 1981 SERIES-6 HARYANA PARTX-B TOWN SURVEY REPORT GURGAON (DISTRICT GURGAON) Drafted by J. R. Vashistha Assistant Director and S.A. Pur; Research Officer Edited by R.K. Aggarwal Deputy Director DIRECTORATE OF CENSUS OPERATIONS, HARYANA, CHANDIGARH lCONTENTS ~ages Foreword v-vi Preface vii-viii, Chapter I Introduction 1-\1 Chapter,1I History of Growth of the Town ,,8;2,,4 Chapter III Amenities and Services - HistorY of Growth and the Present'Positlon 2~§8 Chapter IV Economic Life of the Town 59-t&:4 ChapterV Ethnic and Selected Socio-Demographic Characteristics of the Population 155-2,5 Chapter VI' Migration and Settlement of Families 2,16-317 Chapter VII.: Neighbourhood Pattern 3,18-3,22 ChaPter VIII FamHy Life in the Town 323-352. - Chapter IX Housing and Material Culture 353-4~~ Chapter X Slums, Blighted and Other Areas with Sub-StandarQ Living Conditions ,429-438 ChapterXI Organisation of Power and Prestige 4~9;446 Chapter XII Leisure and Recreation, Social PartiCipation, Social Awareness, Religion and Crim.e 447-q09 Chapter XIII Linkages and Continua ,~'Q-034l ,,' Ch~pter XIV : Conclusion 5p5.~~O Appendix I Particulars of State and Central Government Offices ~1'-~3 Appendix II : Places cOllnected by Haryana Roadway~ Gurgaon Depot,bu_ses with Gurgaoll town MAPS F:~cing page 1. Public Utility Services 4 2. Urban Land Use 4 3, Average Land Value by Wards 22 4, Density of Residential Houses py Wards 22 5. Density of PopL\lation by Wards 22 6. Location of Slum Areas ~~O 7.. Peri-Urban Area S24 iii FOREWORD Apart from the decennial enumeration of population, the Indian Census is steeped In the tradi tion of undertaking a variety of studies of topical interest. -

Gurgaon Limited from Sikanderpur to Sector-56

Detailed Project Report for the South Extension of Rapid MetroRail Gurgaon Limited from Sikanderpur to Sector-56. Updated Detailed Project Report (South Extension) Main Report March 2014 Detailed Project Report (South Extension) Main Report Halcrow Consulting India Pvt. Ltd. A CH2M Hill Company MARCH – 2013 Detailed Project Report for the South Extension of Rapid MetroRail Gurgaon Limited from Sikanderpur to Sector-56. Updated Detailed Project Report (South Extension) Main Report March – 2014 Halcrow Consulting India Pvt. Ltd. A CH2M Hill Company Halcrow Consulting India Private Limited A CH2M Hill Company B-1D, Sector – 10 Noida 201 301 Uttar Pradesh Tel +91 (120) 4682 500 / 4098 900 Fax +91 (120) 4682 534 w w w .halcrow .com Halcrow has prepared this report in accordance w ith the instructions of their client IL & FS Rail Ltd. for their sole and specific use. Any other persons w ho use any information contained herein do so at their ow n risk. © Halcrow Consulting India Private Limited 2014 A CH2M Hill Company Detailed Project Report for the South Extension of Rapid MetroRail Gurgaon Limited from Sikanderpur to Sector-56. Updated Detailed Project Report (South Extension) Main Report Contents Amendment Record This report has been issued and amended as follows: Issue Revision Description Date Prepared by Checked by Issued by Draft Detailed Sumana Ashok Rajesh 1 V0 14.12.12 Project Report Biswas Saxena Chaabra Detailed Sumana Ashok Rajesh 2 V1 31.12.12 Project Report Biswas Saxena Chaabra Detailed Sumana Ashok Rajesh 3 V2 06.12.13 Project -

Map Title Proposed Gurgaon City License Area

Legend M eh Railway rau Industrial Area li N aja Bhart fga hal R rh M oad CityMain Plantation Ro eh ad ra ul i N CityMajor River/Waterbody aj afg arh ExpressHwy Bajghera R ) Hillocks o d ad a o MajorRoad <Double-click here to enter R title> Building n o a g r MinorRoad City Boundary u G ld NationalHwy Neatline O ( d a o StateHwy Buffer R r u ip a Dharampur J ld Choma O Babupur Dandahera Udyog Vihar Surrounding_Area Gurgaon Hero Honda Chowk Palam Vihar Mullahera Dundahera Pawala Khasrupur Cartarpuri Alias Daulatpur N Dundahera Choma Nathupur Mohmadheri Pawala Khasrupur Alla Wardi Cartarpuri Alias Daulatpur N Wazirabad Molahera Kadipur Naharpur Rupa Dunda Hera Daulatabad Ghata Nurpur Jharsa Daultabad Behrampur Bajghera Nangli Umarpur Nawada Fatehpur Maruti Udyog Ghasula Molahera Inayatpur DLF City Ph III Kharki Dola Kanahi MUL Materials Gate Gurgaon DLF City Ph III Gurgaon 32 Mile Stone Narsinghpur Tikampur Shahpur Udyog Vihar Gurgaon (Rural) Fatehpur Daulatabad Industrial AreaGurgaon (Rural) Nathupur Jharsa Begampur Khatola Sarhol DLF City Phase II Babupur Medawas Shamshpur Sihi Tikri Mohmadheri Kherki Daula Dhanwanpur Fazilpur Jharsa Ulhawas Marg Gurgaon Sikanderpur Ghosi Dhanwanpur Kadarpur Sukhrali Mehrauli D L F PHASE I Shahpur Harsaru Gurgaon d Tikampur Garoli Khurd a o R Adampur Badha i lh Bhrempur Chakarpur e Gurgaon DLF City Ph-I D Gurgaon Tahsil Chakarpur Tigra Khandsa Dunda Hera Bindapur Alla Wardi Sikanderpur Badha Hidayatpur Chhawni Darbaripur Silokhra Sukhrali Hassanpur 32 Mile Stone Sikanderpur Ghosi Aklimpur Basai d oa Basai