The Secret History of the Mongols: the Life and Times of Chinggis Khan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Extensions of Remarks

32254 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS September 23, 19 7 6 before the Senate, I move, in accordance CONFffiMATIONS ject to the nominee's commitment to respond with the previous order, that the Senate to requests to appear and testify before any Executive nominations confirmed by duly constituted committee of the Senate. stand in adjournment until the hour of the Senate September 23, 1976: THE JUDICIARY 9 a.m. tomorrow. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH, EDUCATION AND Howard G. Munson, of New York, to be The motion was agreed to; and at 8: 03 WELFARE U.S. district judge for the northern district p.m., the Senate adjourned until tomor Susan B. Gordon, of New Mexico, to be an of New York. Assistant Secretary of Health, Education, and Vincent L. Broderick, of New York to be row, Friday, September 24, 1976, at 9 Welfare. U.S. district judge for the southern dtstrict a.m. The above nomination was approved sub- of New York. EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS THE POLISH NATIONAL ALLIANCE Toastmaster, Felix Mika. attractive for advertisers to distribute their OF YOUNGSTOWN, OHIO Introduction of, Jack c. Hunter, Mayor, brochures unaddressed, as newspaper sup Youngstown, Ohio. • plements for instance, than to distribute Introduction of guests, Toastmaster. them separately to specific people or ad HON. CHARLES J. CARNEY Presentation of honoree, Mary C. Grabow dresses. OF 01!110 ski, Commissioner District 9, PNA. "Our members should be able to use pri Main speaker, Aloysius A. Mazewski, Presi vate delivery companies to deliver advertis IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES dent PNA. ing material just as can be done for maga Thursday, September 23, 1976 Presentation of deb't~tantes, Mary C. -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses The development of the qur'anic calligraphy and illumination under the Mamlukes, 1300-1376 and in Ir James, David Lewis How to cite: James, David Lewis (1982) The development of the qur'anic calligraphy and illumination under the Mamlukes, 1300-1376 and in Ir, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/1984/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 iý THE DEVELOPMENT OF QUR'ANIC CALLIGRAPHY AND ILLUMINATION UNDER THE MAMLUKES 1300- 1376 AND IN IRAQ AND IRAN IN THE SAME PERIOD A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF ARTS !N THE UNIVERSITY OF DURHAM FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DAVID JAMES MA (DUNELM) SUPERVISOR ; DR R. W. J. AUSTIN The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it should be published without his prior written consent and information derived from it should be acknowledged. -

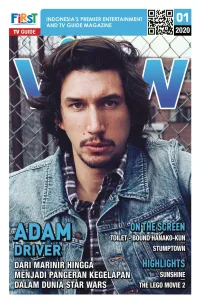

View 202001.Pdf

ON THE SCREEN Premieres Wednesday, January 8 10.10 PM juga adik lelakinya. Di lain sisi, Dex Parios juga berjuang dari rasa traumatis yang ia dapat setelah bertugas sebagai marinir di Afghanistan. Saat itu Premieres, Tuesday ketika ia sedang bertugas sebagai intelijen militer, Dex Parios mengalami ledakan yang membuatnya January 21, 8 PM terluka, dan harus kehilangan orang yang ia cintai. Sementara ia meninggalkan pekerjaannya, ia Sebuah serial televisi Amerika yang pun memutuskan untuk bekerja serabutan demi bertemakan drama kriminal. Dibintangi menghidupi dirinya dan juga adiknya. Hingga oleh Cobie Smulders, Jake Johnson dan pada saatnya, Dex Parios bekerja sebagai Michael Ealy. penyelidik swasta dimana ia bertugas untuk menyelidiki masalah yang tidak bisa dicampuri Teks: Klement Galuh A oleh kepolisian. Dalam perjuangannya tersebut, ia pun mendapat dukungan dari seorang detektif ada serial ini bercerita tentang Dex Parios, bernama Miles Hoffman dan juga Gray McConnel seorang veteran militer cerdas, yang hidup yang mempekerjakan saudara lelaki Dex Parios di P dan berjuang untuk menghidupi dirinya dan bar miliknya. (LMN/MHG/LMN/FIO) 4 Acara “Sacred Sites”, kita diajak untuk mengunjungi tempat-tempat bersejarah yang masih menjadi rahasia dan misteri bagi umat manusia. Kita akan diajak untuk menemukan jawaban-jawaban tersebut melalui acara ini. Teks: Klement Galuh A pakah benar legenda raja Arthur nyata adanya? Pertanyaan tersebut akan dikupas menggunakan A terobosan ilmiah dan penelitian arkeologis untuk membawa kita kepada perspektif baru ke beberapa lokasi religi yang luar biasa, namun juga misterius. Dalam setiap episodenya, acara ini akan berfokus pada satu situs dan mengeksplorasi situs tersebut. Dimulai dari orang-orang yang membangunnya, hingga menjawab pertanyaan mendasar dari orang-orang yang melihat bangunan tersebut. -

Protagonist of Qubilai Khan's Unsuccessful

BUQA CHĪNGSĀNG: PROTAGONIST OF QUBILAI KHAN’S UNSUCCESSFUL COUP ATTEMPT AGAINST THE HÜLEGÜID DYNASTY MUSTAFA UYAR* It is generally accepted that the dissolution of the Mongol Empire began in 1259, following the death of Möngke the Great Khan (1251–59)1. Fierce conflicts were to arise between the khan candidates for the empty throne of the Great Khanate. Qubilai (1260–94), the brother of Möngke in China, was declared Great Khan on 5 May 1260 in the emergency qurultai assembled in K’ai-p’ing, which is quite far from Qara-Qorum, the principal capital of Mongolia2. This event started the conflicts within the Mongolian Khanate. The first person to object to the election of the Great Khan was his younger brother Ariq Böke (1259–64), another son of Qubilai’s mother Sorqoqtani Beki. Being Möngke’s brother, just as Qubilai was, he saw himself as the real owner of the Great Khanate, since he was the ruler of Qara-Qorum, the main capital of the Mongol Khanate. Shortly after Qubilai was declared Khan, Ariq Böke was also declared Great Khan in June of the same year3. Now something unprecedented happened: there were two competing Great Khans present in the Mongol Empire, and both received support from different parts of the family of the empire. The four Mongol khanates, which should theo- retically have owed obedience to the Great Khan, began to act completely in their own interests: the Khan of the Golden Horde, Barka (1257–66) supported Böke. * Assoc. Prof., Ankara University, Faculty of Languages, History and Geography, Department of History, Ankara/TURKEY, [email protected] 1 For further information on the dissolution of the Mongol Empire, see D. -

Power, Politics, and Tradition in the Mongol Empire and the Ilkhanate of Iran

OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 08/08/16, SPi POWER, POLITICS, AND TRADITION IN THE MONGOL EMPIRE AND THE ĪlkhānaTE OF IRAN OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 08/08/16, SPi OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 08/08/16, SPi Power, Politics, and Tradition in the Mongol Empire and the Īlkhānate of Iran MICHAEL HOPE 1 OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 08/08/16, SPi 3 Great Clarendon Street, Oxford, OX2 6D P, United Kingdom Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries © Michael Hope 2016 The moral rights of the author have been asserted First Edition published in 2016 Impression: 1 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by licence or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Data available Library of Congress Control Number: 2016932271 ISBN 978–0–19–876859–3 Printed in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, St Ives plc Links to third party websites are provided by Oxford in good faith and for information only. -

UYGHUR STUDIES in CENTRAL ASIA: a Historical Review

UYGHUR STUDIES IN CENTRAL ASIA 3 ABLET KAMALOV UYGHUR STUDIES IN CENTRAL ASIA: A Historical Review INTRODUCTION The Uyghurs, a Turkic people comprising a major part of the population of the Xinjiang-Uyghur Autonomous Region (XUAR), China, also have sizable communities in the former Soviet Central Asian Republics, espe- cially in Kazakhstan, where they numbered 220,000 in 1999 (altogether the Uyghur population in the newly independent states numbers more than 300,000). The Central Asian Uyghur community played a signifi- cant role in the Uyghur nation-building process as well as in Soviet- Chinese relations during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. The Soviet authorities used the Uyghurs as a tool in their policy toward Xinjiang (Eastern Turkistan) and for that purpose provided special sup- port for the development of Uyghur culture in Central Asia. A significant part of that policy was the development of Uyghur studies in Central Asia, particularly in Kazakhstan, which became a cultural center for the Soviet Uyghurs. Uyghur studies covers mostly the research done in the sphere of language, literature, history, and culture (art, music, etc). This article will examine the history of Uyghur studies in Soviet Central Asia and outline its trends. 4 KAMALOV THE MAIN STAGES The Initial Stage (1920–1945) The earliest research on Uyghurs conducted in Central Asia exhibited mostly a practical character. The purpose was to pursue specific goals of Soviet national policy aimed at the creation of new socialist “nations” in the region. The Uyghurs, along with other peoples, were recognized by the Soviet state as a “nation” during the period of national delimitation and demarcation in Central Asia during the early 1920s, just after the establishment of Bolshevik power. -

December 31, 2017 - January 6, 2018

DECEMBER 31, 2017 - JANUARY 6, 2018 staradvertiser.com WEEKEND WAGERS Humor fl ies high as the crew of Flight 1610 transports dreamers and gamblers alike on a weekly round-trip fl ight from the City of Angels to the City of Sin. Join Captain Dave (Dylan McDermott), head fl ight attendant Ronnie (Kim Matula) and fl ight attendant Bernard (Nathan Lee Graham) as they travel from L.A. to Vegas. Premiering Tuesday, Jan. 2, on Fox. Join host, Lyla Berg, as she sits down with guests Meet the NEW SHOW WEDNESDAY! who share their work on moving our community forward. people SPECIAL GUESTS INCLUDE: and places Mike Carr, President & CEO, USS Missouri Memorial Association that make Steve Levins, Executive Director, Office of Consumer Protection, DCCA 1st & 3rd Wednesday Dr. Lynn Babington, President, Chaminade University Hawai‘i olelo.org of the Month, 6:30pm Dr. Raymond Jardine, Chairman & CEO, Native Hawaiian Veterans Channel 53 special. Brandon Dela Cruz, President, Filipino Chamber of Commerce of Hawaii ON THE COVER | L.A. TO VEGAS High-flying hilarity Winners abound in confident, brash pilot with a soft spot for his (“Daddy’s Home,” 2015) and producer Adam passengers’ well-being. His co-pilot, Alan (Amir McKay (“Step Brothers,” 2008). The pair works ‘L.A. to Vegas’ Talai, “The Pursuit of Happyness,” 2006), does with the company’s head, the fictional Gary his best to appease Dave’s ego. Other no- Sanchez, a Paraguayan investor whose gifts By Kat Mulligan table crew members include flight attendant to the globe most notably include comedic TV Media Bernard (Nathan Lee Graham, “Zoolander,” video website “Funny or Die.” While this isn’t 2001) and head flight attendant Ronnie the first foray into television for the produc- hina’s Great Wall, Rome’s Coliseum, (Matula), both of whom juggle the needs and tion company, known also for “Drunk History” London’s Big Ben and India’s Taj Mahal demands of passengers all while trying to navi- and “Commander Chet,” the partnership with C— beautiful locations, but so far away, gate the destination of their own lives. -

The Great Empires of Asia the Great Empires of Asia

The Great Empires of Asia The Great Empires of Asia EDITED BY JIM MASSELOS FOREWORD BY JONATHAN FENBY WITH 27 ILLUSTRATIONS Note on spellings and transliterations There is no single agreed system for transliterating into the Western CONTENTS alphabet names, titles and terms from the different cultures and languages represented in this book. Each culture has separate traditions FOREWORD 8 for the most ‘correct’ way in which words should be transliterated from The Legacy of Empire Arabic and other scripts. However, to avoid any potential confusion JONATHAN FENBY to the non-specialist reader, in this volume we have adopted a single system of spellings and have generally used the versions of names and titles that will be most familiar to Western readers. INTRODUCTION 14 The Distinctiveness of Asian Empires JIM MASSELOS Elements of Empire Emperors and Empires Maintaining Empire Advancing Empire CHAPTER ONE 27 Central Asia: The Mongols 1206–1405 On the cover: Map of Unidentified Islands off the Southern Anatolian Coast, by Ottoman admiral and geographer Piri Reis (1465–1555). TIMOTHY MAY Photo: The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore. The Rise of Chinggis Khan The Empire after Chinggis Khan First published in the United Kingdom in 2010 by Thames & Hudson Ltd, 181A High Holborn, London WC1V 7QX The Army of the Empire Civil Government This compact paperback edition first published in 2018 The Rule of Law The Great Empires of Asia © 2010 and 2018 Decline and Dissolution Thames & Hudson Ltd, London The Greatness of the Mongol Empire Foreword © 2018 Jonathan Fenby All Rights Reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced CHAPTER TWO 53 or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, China: The Ming 1368–1644 including photocopy, recording or any other information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. -

Gamification: Is It Right for Your Library?

AALLCovApr2013:Layout 1 3/13/13 9:40 AM Page 1 AALLI Spectrum Volume 17 No. 6 April 2013 AALL: Maximizing the Power of the Law Library Community Since 1906 In This Issue 10 How cloud services can enhance collaboration 18 Learn about Seattle with the co-chairs of the Local Arrangements Committee 21 E-lending in academic law libraries 07 Gamification: Is it Right for Your Library? www.aallnet.org AALLCovJuly2012:Layout 1 6/13/12 3:57 PM Page 4 Advance™ AALLApr2013:1 3/13/13 10:32 AM Page 1 Vol. 17, No. 6 April 2013 from the editor By Mark E. Estes AALL Spectrum® Initial Reactions Editorial Staff “Hello from an ‘old’ friend . ” and I am sure I would have received Marketing and Communications Manager Ashley St. John [email protected] read the subject line of an email many more shirts and ties had I hidden message that recently showed up in my Editorial Director my initial disappointment. Mark E. Estes [email protected] Outlook inbox. It seemed suspiciously Two of the 36 responses we received Copy Editor Robert B. Barnett Jr. spamish, but I kept reading because to this month’s Member to Member Graphic Designer Kathy Wozbut I could see the content in the preview question provide examples of inaccurate pane: or inappropriate first reactions. In case 2012–2013 Law Library Journal and AALL Spectrum Committee you’ve forgotten the question or haven’t Chair Linda C. Corbelli Hey Mark, already read this issue’s Member to Vice Chair Amanda Runyon Remember me, Tim C.? Member responses, we asked: Members I Googled you, and I think “What is one word or phrase you Judy K. -

Inscriptions. Nevertheless, the Mongols Had a Language and Character of Their Own, and This Appears at Intervals Upon Their Coins

00087560 BOMBAY BRANCH OF THU ROYAL ASIATIC SOCIETY, )fi TOWN HALL, BOMBAY. Ss :4 Digitized with financial assistance from the Government of Maharashtra on 18 July, 2018 CATALOGUE ORIENTAL COINS IN THE BRITfSH iMUSEUM. VOL. VI. LONDON: PRINTED BY ORDER OF THE TRUSTEES. Longmans & Co., Paternoster Row ; B. M. P ickering , 66, Haymarket ; B. Quaritch, 15, Piccadilly ; A. A sher & Co.> 13, Bedford Street, Covent Garden, and at Berlin; TrubneR & Co, 57 & 59 L ddgate Hill. Paris : MM. C. Rollin & Feuardent , 4, Rue de Louvois . 1881. LONDON : GILBERT AND RIVINGTON, ST. J o h n ’s sq u a r e , clerkenwkll . 00087560 00087560 THE COINS OF THE MONGOLS IN THB^ BRITISH MUSEUM. CLASSES XVIII.—XXII. BY STANLEY LANE-POOLE. ed ite d by REGINALD STUART POOLE, CORRESPONDENT OF THE INSTITUTE OP FRANCE. LONDON PRINTED BY ORDER OF THE TRUSTEES. i88i. EDITOB’S PREFACE. T h is Sixth Volume of the Catalogue of Oriental Coins in the British Museum deals with the money issued by the Mongol Dynasties descended from Jingis Khan, correspond ing to Praehn’s Classes XVIII.—XXII. The only line of Khans tracing their lineage to Jingis excluded from this Yolume is that of Sheyban or Abu-l*KhOyr, which Was of late foundation and rose on the ruins of the Timurian empire. Timur’s own coinage, with that of his house, is reserved for the next (or Seventh) Volume, since he was not a lineal descendant of Jingis. On the other hand, the issues of the small dynasties which divided Persia among them between the decay of the Ilkhans and the invasion of Timur are included in this volume as a species of appendix. -

Mongol Invasions of Northeast Asia Korea and Japan

Eurasian Maritime History Case Study: Northeast Asia Thirteenth Century Mongol Invasions of Northeast Asia Korea and Japan Dr. Grant Rhode Boston University Mongol Invasions of Northeast Asia: Korea and Japan | 2 Maritime History Case Study: Northeast Asia Thirteenth Century Mongol Invasions of Northeast Asia Korea and Japan Contents Front piece: The Defeat of the Mongol Invasion Fleet Kamikaze, the ‘Divine Wind’ The Mongol Continental Vision Turns Maritime Mongol Naval Successes Against the Southern Song Korea’s Historic Place in Asian Geopolitics Ancient Pattern: The Korean Three Kingdoms Period Mongol Subjugation of Korea Mongol Invasions of Japan First Mongol Invasion of Japan, 1274 Second Mongol Invasion of Japan, 1281 Mongol Support for Maritime Commerce Reflections on the Mongol Maritime Experience Maritime Strategic and Tactical Lessons Limits on Mongol Expansion at Sea Text and Visual Source Evidence Texts T 1: Marco Polo on Kublai’s Decision to Invade Japan with Storm Description T 2: Japanese Traditional Song: The Mongol Invasion of Japan Visual Sources VS 1: Mongol Scroll: 1274 Invasion Battle Scene VS 2: Mongol bomb shells: earliest examples of explosive weapons from an archaeological site Selected Reading for Further Study Notes Maps Map 1: The Mongol Empire by 1279 Showing Attempted Mongol Conquests by Sea Map 2: Three Kingdoms Korea, Battle of Baekgang, 663 Map 3: Mongol Invasions of Japan, 1274 and 1281 Map 4: Hakata Bay Battles 1274 and 1281 Map 5: Takashima Bay Battle 1281 Mongol Invasions of Northeast Asia: Korea and -

AH Istory of L and U Se in M Ongolia

A H istory of L and Use in Mongolia A H istory of L and Use in Mongolia The Thirteenth Century to the Present ELIZABETH ENDICOTT A HISTORY OF LAND USE IN MONGOLIA Copyright © Elizabeth Endicott, 2012. Softcover reprint of the hardcover 1st edition 2012 978-1-137-26965-2 All rights reserved. First published in 2012 by PALGRAVE MACMILLAN® in the United States— a division of St. Martin’s Press LLC, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010. Where this book is distributed in the UK, Europe and the rest of the world, this is by Palgrave Macmillan, a division of Macmillan Publishers Limited, registered in England, company number 785998, of Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire RG21 6XS. Palgrave Macmillan is the global academic imprint of the above companies and has companies and representatives throughout the world. Palgrave® and Macmillan® are registered trademarks in the United States, the United Kingdom, Europe and other countries. I SBN 978-1-349-44403-8 ISBN 978-1-137-26966-9 (eBook) DOI 10.1057/9781137269669 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data. Endicott, Elizabeth. A history of land use in Mongolia : the thirteenth century to the present / Elizabeth Endicott. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. 1. Land use—Mongolia—History. 2. Land use, Rural—Mongolia— History. 3. Rangelands—Mongolia—History. 4. Herders—Mongolia— History. I. Title. HD920.8.E53 2012 333.73Ј1309517—dc23 2012016618 A catalogue record of the book is available from the British Library. Design by Newgen Imaging Systems (P) Ltd., Chennai, India. First