American Folklife Center

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Women Neuropsychiatrists on Wagner-Jauregg's Staff in Vienna at the Time of the Nobel Award: Ordeal and Fortitude

History of Psychiatry Women neuropsychiatrists on Wagner-Jauregg’s staff in Vienna at the time of the Nobel award: ordeal and fortitude Lazaros C Triarhou University of Macedonia, Greece Running Title: Women Neuropsychiatrists in 1927 Vienna Corresponding author: Lazaros C. Triarhou, Laboratory of Theoretical and Applied Neuroscience and Graduate Program in Neuroscience and Education, University of Macedonia, Egnatia 156, Thessalonica 54006, Greece. E-Mail: [email protected] ORCID id: 0000-0001-6544-5738 2 Abstract This article profiles the scientific lives of six women on the staff of the Clinic of Neurology and Psychiatry at the University of Vienna in 1927, the year when its director, Julius Wagner-Jauregg (1857–1940), was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine. They were all of Jewish descent and had to leave Austria in the 1930s to escape from the National Socialist regime. With a solid background in brain science and mental disorders, Alexandra Adler (1901–2001), Edith Klemperer (1898–1987), Annie Reich (1902–1971), Lydia Sicher (1890– 1962) and Edith Vincze (1900–1940) pursued academic careers in the United States, while Fanny Halpern (1899–1952) spent 18 years in Shanghai, where she laid the foundations of modern Chinese psychiatry, before going to Canada. At the dawn of their medical career, they were among the first women to practice neurology and psychiatry both in Austria and overseas. Keywords Women in psychiatry, Jewish physicians, University of Vienna, Interwar period, Austrian Annexation 3 Introduction There is a historic group photograph of the faculty and staff of the Neurology and Psychiatry Clinic in Vienna, taken on 7 November 1927 (Figure 1). -

Friends of the BC Archives Newsletter November 2017 Vol

1 Friends of the BC Archives Newsletter November 2017 Vol. 17, No. 1 In this Issue: Ø New FBCA Board Members, 2 Ø Upcoming Events, 3 Ø Introductions: New Staff at the BC Archives, 4 Ø Recent Events, 5-6 Retiring FBCA Board Members At our annual general meeting this past October we acknowledged with appreciation the service of five directors who retired from our Board: Marie Elliott, Patricia Roy, Ron Welwood, Sue Baptie, and Patricia Dirks. • Marie Elliot is one of our founding members. Her name is on our inaugural constitution, when our society was incorporated seventeen years ago, on 20 September 2000. She was vice-president in the first year of the FBCA and president from 2003-2005. Thereafter, Marie was a director and the society’s secretary (and thanks to the meticulous minutes that Marie kept over the years, we can document the tenure of our other directors). • Dr. Patricia Roy, Professor Emeritus at the University of Victoria, joined the FBCA Board in 2003. In 2010, Pat was elected president and she later served as a director-at-large from 2012 to 2017. • Ron Welwood, who resides in Nelson, BC, was elected for the first time at the AGM in 2006 and for the next decade was our ‘external’ director – a Board member who does not reside in Greater Victoria. For many years, he was the editor of British Columbia History, the journal of the BC Historical Federation. • Sue Baptie, former chief archivist for the City of Vancouver, became a member of the FBCA Board in 2006. -

Indian Music of the Pacific Northwest: an Annotated Bibliography of Research IAN L

Indian Music of the Pacific Northwest: An Annotated Bibliography of Research IAN L. BRADLEY Few aspects of North American Indian history are as rewarding to study as the cultural achievements of the aboriginal inhabitants of the Pacific Northwest. Ever since the early studies of Boas, Niblack, Haeberlin, Em mons and Swan, a growing interest has generated hundreds of articles and accounts of the artistic achievements of the natives in this area. Unfor tunately much of the early literature lies hidden in obscure journals dating back to the late nineteenth century, and remains relatively unknown to all but the interested scholar. In earlier research the writer prepared an extensive bibliography1 which documented over 700 titles encompassing native achievements in the creative arts. It included scholarly studies, catalogues of exhibitions, and a large body of literature which describes and illustrates the many diverse facets of native plastic and graphic art, dance, and music. From this interest there developed a growing conviction that early research in native Indian music generated by such scholars as Fillmore, Galpin, Densmore and Barbeau would be useful and pertinent for the development of educa tional curricula in both native studies and music. Furthermore, the infor mation stored in many of these historical accounts could be of great interest to teachers and students wishing to further investigate the signifi cant musical culture of the indigenous tribes of the region. This compilation is the result of a systematic search through the Pacific Northwest collection in the University of Washington Library, the main catalogues of the University of British Columbia, the University of Vic toria, and the British Columbia Provincial Archives library. -

Moses and Frances Asch Collection, 1926-1986

Moses and Frances Asch Collection, 1926-1986 Cecilia Peterson, Greg Adams, Jeff Place, Stephanie Smith, Meghan Mullins, Clara Hines, Bianca Couture 2014 Ralph Rinzler Folklife Archives and Collections Smithsonian Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage 600 Maryland Ave SW Washington, D.C. [email protected] https://www.folklife.si.edu/archive/ Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Arrangement note............................................................................................................ 3 Biographical/Historical note.............................................................................................. 2 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 2 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 3 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 5 Series 1: Correspondence, 1942-1987 (bulk 1947-1987)........................................ 5 Series 2: Folkways Production, 1946-1987 (bulk 1950-1983).............................. 152 Series 3: Business Records, 1940-1987.............................................................. 477 Series 4: Woody Guthrie -

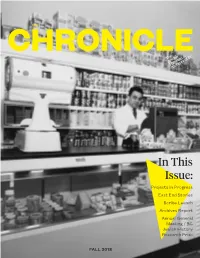

In This Issue: Projects in Progress East End Stories Scribe Launch Archives Report Annual General Meeting / BC Jewish History Research Prize

In This Issue: Projects in Progress East End Stories Scribe Launch Archives Report Annual General Meeting / BC Jewish History Research Prize FALL 2018 Founded in 1971 as the Jewish Historical Society of British Columbia Founding President: Cyril Leonoff, z”l The Chronicle BOARD STAFF Volume 24, Issue 2 © JMABC, 2018 President Administrator Perry Seidelman Marcy Babins Cover Image: Vice President Archivist Dave Shafran, Carol Herbert Alysa Routtenberg owner of Max’s Treasurer Delicatessen, Alisa Franken Director of Community tending the till, Engagement circa 1960. Secretary Michael Schwartz Gordon Brandt L.09267 Members-At-Large Editing and Design Alan Farber Michael Schwartz Phil Sanderson Immediate Past President Gary Averbach We gratefully acknowledge the generous support of our Directors sponsors: Oren Bick David Bogoch Betty Averbach Foundation Alex Farber City of Vancouver Daniella Givon Diamond Foundation Bill Gruenthal Adam Korbin Government of Canada Evan Orloff Jewish Community Foundation Ronnie Tessler Michael Tripp Jewish Federation of Greater Vancouver Council of Governors Isabelle Diamond Phyliss and Irving Snider Marie Doduck Foundation Michael Geller Province of British Columbia Bill Gruenthal Richard Henriquez Waldman Foundation Cyril Leonoff z”l Risa Levine Josephine Margolis Nadel Richard Menkis Ronnie Tessler The Jewish Museum and Archives of BC is a registered non- profit with CRA # 10808 5259 RR0001. All contributions are tax-deductable. 1 President’s Message How many of us wish we knew more about our to see, hear, and touch the history. They grandparents’ history? How many of us wonder where should collect, maintain and exhibit, and then old photos or historical documents ended up after a bequeath, the entire family tradition. -

Semnewsletter

SEM Newsletter Published by the Society for Ethnomusicology Volume 41 Number 1 January 2007 President’s Report: The one replete with challenges. To address the Becoming Ethnomusi- theme of “Decolonizing Ethnomusicology” Society for Ethnomusi- we turned not to the histories enacted by cologists cology Makes a Differ- others, but rather to those scripted, often By Philip V. Bohlman, SEM President with force, by selves, indeed, ourselves. The ence groundswell of papers and presentations I turn to my column in the SEM News- By Philip V. Bohlman, SEM President that addressed the ways we ourselves have letter (pp. 4-5) in the aftermath of the 51st been responsible for colonizing others and Annual Meeting of the Society, which took As the Society for Ethnomusicology silencing others, even as we imagined we were as its overarching theme “Decolonizing enters its second half-century, all accounts giving them voice, was impressive indeed, Ethnomusicology.” From the moment of lead to the conclusion that we are ready to not because it was cause for celebrating our its announcement the theme became a light- engage new challenges and embrace new history, but because it presented us squarely ning rod for papers and panels of all kinds. opportunities. The SEM emerged from its with a new challenge from history. Our his- Its impact on the program for the annual 50th anniversary meeting in Atlanta having tory is a history of responsibility. It is and meeting could not have been more palpable. set new records for attendance and participa- also must be a history of response. This is Approached with a sense of responsibil- tion. -

Friends of the British Columbia Archives Is Open to Everyone and Covers the Year from September to August

1 Friends of the NEWSLETTER British Columbia Archives Vol. 14, No. 5 Royal BC Museum to Launch Crowd-Sourcing Transcription Site, Transcribe This spring the Royal BC Museum will launch Transcribe, a crowd-sourcing website that will allow the public to transcribe valuable historical records. The project aims to improve the Royal BC Museum and Archives’ public accessibility by turning handwritten, audio, and video records into searchable data. By donating their time to transcribe letters, diaries, journals, and other materials Transcribe volunteers can help share BC’s history from the comfort of home. Crowd-sourcing is an increasingly popular way for archives and museums to improve the accessibility of their collections. The concept behind Transcribe is simple – the Royal BC Museum provides digital photographs of archival materials alongside a blank text area and users type exactly what they see. Volunteers simply visit the website, choose a collection and begin to transcribe, all on their own time. The finished transcriptions are reviewed and approved by Royal BC Museum staff and the data becomes searchable on the Transcribe site. The project was initiated by the New Archives and Digital Preservation department and Archivist Ann ten Cate. “We wanted to enlist the help of volunteers to make our collections more accessible,” said Ember Lundgren, Preservation Manager. “There’s a huge, untapped resource of talented and enthusiastic volunteers, just waiting to help out. Transcribe will help us use that resource. Plus, it’s fun!” 1 Lundgren notes that visitors are not obligated to transcribe work; they will also have the option to view the materials as an online exhibition, and browse existing transcriptions. -

Ethnomusicologists X Ethnomusicologists Features Ethnomusicologists X Terry E

Volume 49, Number 1 Winter 2015 Ethnomusicologists x Ethnomusicologists Features Ethnomusicologists x Terry E. Miller Interviewed by Patricia Shehan Campbell Ethnomusicologists [1, Born and raised in Dover, Ohio, Terry E. Miller has studied the musics of Mainland 4, 6, 8] Southeast Asia (especially Thailand, Laos, and Vietnam), China, and oral traditions in President’s Report hymnody in the Americas, the West Indies, and the United Kingdom. Having taught at President Beverley Kent State University for 30 years (he retired in 2005) he is an active member of The Diamond [3, 5] Siam Society, the Society for Ethnomusicology (Treasurer, 1995-2000), the American Musicological Society, the Society for American Music, and the Society for Asian Music (President, 1994-1999). He founded the Kent State University Thai Ensemble in 1978 (which continues to this day as the only active Thai ensemble in the U.S.) and KSU Chinese Ensemble (1988-2005). His published scholarship includes Traditional Music of SEM the Lao: Kaen Playing and Mawlum Singing in Northeast Thailand (1985), The Garland Encyclopedia of World Music: Volume 4, Southeast Asia, A History of Siamese Music Announcements Reconstructed from Western Documents, 1505-1932 (with Jarernchai Chonpairot, 2004), SEM Prizes, and World Music: A Global Journey (with Andrew Shariari, 2012, third edition). His Tina Ramnarine [5, 7] recordings for Lyrichord, World Music Institute, and New Alliance Records include New Honorary Members Americans: Music of Laos—Khamvong Isiziengmai, The Song of the Phoenix: Sheng Portia K. Maultsby by Ei- Music from China, Thailand: Lao Music of the North- leen Hayes [11] east, Vietnam: Mother Mountain and Father Sea, and Adrienne Kaeppler, Ricardo Eternal Voices: Traditional Vietnamese Music in the Trimillos [12] United States (with Phong Nguyen). -

Ida Halpern: a Post-Colonial Portrait of a Canadian Pioneer Ethnomusicologist Kenneth Chen

Document generated on 09/27/2021 6:46 a.m. Canadian University Music Review Revue de musique des universités canadiennes Ida Halpern: A Post-Colonial Portrait of a Canadian Pioneer Ethnomusicologist Kenneth Chen Voices of Women: Essays in Honour of Violet Archer Article abstract Voix de femmes : mélanges offerts à Violet Archer The work of Ida Halpern (1910–87), one of Canada's first musicologists and a Volume 16, Number 1, 1995 pioneer ethnomusicologist, has been largely ignored. This essay illuminates her most important contribution to the musical development of this country: URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1014415ar the documentation of Native musics. Halpern devoted some four decades to DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/1014415ar recording and analyzing over five hundred songs of the Kwakwaka'wakw, the Nuuchahnulth, the Haida, the Nuxalk, and the Coast Salish First Nations of British Columbia—a truly remarkable achievement considering that a large See table of contents part of her fieldwork was conducted during a period when it was illegal for Native cultures to be celebrated, much less preserved. The author discusses the strengths and weaknesses of her methodology as well as some factors affecting Publisher(s) the reception of her work by academic peers and by the communities she worked with. While Halpern did not always thoroughly investigate context, she Canadian University Music Society / Société de musique des universités endeavoured to write heteroglossically and to invent a theory that accounted canadiennes for the music of these songs. ISSN 0710-0353 (print) 2291-2436 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this article Chen, K. -

The Canadian Commission for UNESCO Reveals the First Inscriptions to the Canada Memory of the World Register

The Canadian Commission for UNESCO reveals the first inscriptions to the Canada Memory of the World Register Ottawa, March 27, 2018 - For immediate release The Canadian Commission for UNESCO announced today at a press conference held at the Royal BC Museum six new inscriptions to the Canada Memory of the World Register. The event, intended for media and partners of the Canadian Commission for UNESCO and the Royal BC Museum, featured a presentation from collections holders such as the Royal BC Museum, Library and Archives Canada, National Film Board of Canada and Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec (BAnQ). One of the highlights of the event was an interpretation of sacred songs that were part of the lda Halpern collection, submitted by the Royal BC Museum to the Canada Memory of the World Register. The Canoe Paddle Song and the Farewell Song, originally sung by Peter Webster, were interpreted again today by his great-grandson, Guy Louie, accompanied by his mother Pamela Webster and his uncle Hudson Webster. The purpose of the Memory of the World Program, created by UNESCO in 1992, is to facilitate the preservation of documentary heritage and ensure access to it. The international register and national registers objective is to raise awareness about the importance of documentary heritage as the “memory” of humanity. The Canadian Advisory Committee for Memory of the World review applications and make recommendation for both the International Register and the Canada Memory of the World Register. In creating the Canada Memory of the World Register in May 2017, the Canadian Commission for UNESCO wanted it to be the reflection of the immense diversity of the documentary heritage that is significant to Canada whose roots extend from the initial settling of the land by Indigenous Peoples up to the present time. -

Hidden Histories

SONNY ASSU HIDDEN HISTORIES At the invitation of Kwak’wala Chief Billy Assu in 1947, Viennese-born ethnomusicologist Dr. Ida Halpern recorded the ceremonial songs of the Kwakwaka’wakw peoples from a territory that is now known as Vancouver Island, British Columbia.1 Amongst the recordings are those of Chief Billy Assu, the hereditary leader of the First Peoples of Cape Mudge. The over 342 ceremonial songs recorded by Halpern were central to potlatch ceremonies.2 The period of the recordings is particularly significant: it was a time when the Canadian government’s potlatch ban sought to drastically suppress and outright disavow the ceremonial traditions of Indigenous peoples from the Pacific Northwest Coast. An amendment to the Indian Act in 1884 criminalized FIG. 4 What a Great Spot for a Walmart! (2014) FIG. 2 FIG. 3 Silenced: The Burning (2011) #photobomb (2013) FIG. 1 COVER Billy and the Chiefs: The Complete Banned Collection (detail, The Feast Collection, 2012) the potlatch, a highly structured ceremonial gift- Davies points out, each drum not only marks each giving feast that had united villages for centuries.3 year of the potlatch ban but were also “intended Eventually repealed in 1951, the law had ensured to generate rhythm and noise, and unify the that seized ceremonial potlatch items such as members of a community, these drums now lie regalia and masks left communities and often silent on the floor.”9 made their way into museum collections across Canada, England and the United States.4 In addition to asserting and contextualizing suppressed histories, the use of internet-speak Halpern’s recordings of leaders such as Chief presents a much more contemporary dimension Billy Assu, Mungo Martin, George Clutesi, Dan to his print and painting practice. -

Working Towards Indigenizing the BC Archives

From Documents to People: Working Towards Indigenizing the BC Archives Genevieve Weber Introduction n 2015, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (TRC) issued ninety-four calls to action – policy and program rec- ommendations created to promote the reconciliation of Indigenous Iand settler societies in Canada.1 Although a small number of these are specifically aimed at Canadian museums and archives, many of the calls indirectly affect the work that archivists do. One thing is clear from reading the calls to action: they are about people. Although each call addresses an area of weakness in policy or common practice, the outcomes are intended to benefit people, Indigenous and non-Indigenous. Embedded within the mandate of the TRC and its calls to action is an understanding of the contradictory power of archives: as deeply colonial institutions, archives have the ability to choose which voices are heard. They have the power to shape history and determine which stories are learned by future generations and which are forgotten.2 They can also choose which version of the story is preserved: “Archives power includes the power to hurt through derogatory, colonial and hateful words.”3 The imbalance of power in the official record illustrates the disenfran- chisement and disinheritance of Indigenous rights.4 At the same time, archives also have the ability to give evidence, to raise awareness and share the burden, and the potential to heal through understanding the past, and in this way they are also “pathways for Indigenous people and communities to recognize injustice and begin to heal, and for Indigenous 1 Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada: Calls to Action (Winnipeg: Truth and Reconciliation Commission, 2015).