The Uluru Statement: a First Nations Perspective of the Implications for Social Reconstructive Race Relations in Australia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Appendix a (PDF 85KB)

A Appendix A: Committee visits to remote Aboriginal and Torres Strait communities As part of the Committee’s inquiry into remote Indigenous community stores the Committee visited seventeen communities, all of which had a distinctive culture, history and identity. The Committee began its community visits on 30 March 2009 travelling to the Torres Strait and the Cape York Peninsula in Queensland over four days. In late April the Committee visited communities in Central Australia over a three day period. Final consultations were held in Broome, Darwin and various remote regions in the Northern Territory including North West Arnhem Land. These visits took place in July over a five day period. At each location the Committee held a public meeting followed by an open forum. These meetings demonstrated to the Committee the importance of the store in remote community life. The Committee appreciated the generous hospitality and evidence provided to the Committee by traditional owners and elders, clans and families in all the remote Aboriginal and Torres Strait communities visited during the inquiry. The Committee would also like to thank everyone who assisted with the administrative organisation of the Committee’s community visits including ICC managers, Torres Strait Councils, Government Business Managers and many others within the communities. A brief synopsis of each community visit is set out below.1 1 Where population figures are given, these are taken from a range of sources including 2006 Census data and Grants Commission figures. 158 EVERYBODY’S BUSINESS Torres Strait Islands The Torres Strait Islands (TSI), traditionally called Zenadth Kes, comprise 274 small islands in an area of 48 000 square kilometres (kms), from the tip of Cape York north to Papua New Guinea and Indonesia. -

Periodic Report on the State of Conservation of Uluru-Kata Tjuta

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL PERIODIC REPORT SECTION II Report on the State of Conservation of Uluru – Kata Tjuta National Park ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ Periodic Report 2002 - Section II Uluru - Kata Tjuta National Park 1 ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- II.1. INTRODUCTION a. State Party Australia b. Name of World Heritage property Uluru - Kata Tjuta National Park c. Geographical coordinates to the nearest second Uluru - Kata Tjuta National Park is located in Central Australia, in the south-western corner of the Northern Territory, at latitude 25°05’ - 25°25’ south and longitude 130°40’ - 131° east. d. Date of inscription on the World Heritage List Uluru - Kata Tjuta National Park was nominated and inscribed on the World Heritage List for natural values in 1987 under natural criteria (ii) and (iii). Uluru - Kata Tjuta National Park was renominated and inscribed on the World Heritage List as a Cultural Landscape in 1994 under cultural criteria (v) and (vi). e. Organization(s) or entity(ies) responsible for the preparation of the report This report was prepared by Parks Australia, in association with the Heritage Management Branch of the Department of the Environment and Heritage. II.2. STATEMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE Criteria Uluru - Kata Tjuta -

Outback Australia - the Colour of Red

Outback Australia - The Colour of Red Your itinerary Start Location Visited Location Plane End Location Cruise Train Over night Ferry Day 1 healing. The flickering glow of this evening's fire, dancing under the canopy of a Arrive Ayers Rock (2 Nights) starry Southern Hemisphere sky, is the perfect accompaniment to your Regional 'Under a Desert Moon' Meal. This degustation menu with matching wines is the Feel the stirring of something bigger than you as you arrive in Ayers Rock Resort perfect end to the day. Sit back and listen to the sounds of the outback come alive (flights to arrive prior to 2pm), only 20 km from magical, mystical Uluru and the at night in the company of new friends. launchpad to Australia's spiritual heart in the Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Park. This afternoon, you'll travel to Uluru as the day fades away, the outback sun bidding a Hotel - Kings Canyon Resort, Deluxe Spa Rooms fiery farewell. Uluru towers over the Northern Territory's remote landscape, the perfect backdrop for this evening's Welcome Reception. Included Meals - Breakfast, Lunch, Regional Dinner Day 4 Hotel - Sails in the Desert, Ayers Rock Resort Kings Canyon - Alice Springs Included Meals - Welcome Reception Gaze across the deep chasm at the edge of Kings Canyon as you embark on the Day 2 spellbinding 6 km sunrise Rim Walk, past the sandstone domes of the 'Lost City' Uluru Sightseeing and down the stairs to the lush 'Garden of Eden'. Or you can opt for a gentler stroll along the canyon creek bed, treading in the footsteps of the Luritja people Wake early, taking time to pause and contemplate the mesmerising sunrise over who once found sanctuary amidst the Itara trees at the base of the canyon. -

Manyitjanu Lennon

Manyitjanu Lennon Born c. 1940 Language Group Pitjantjatjara Region APY Lands Biography Manyitjanu Lennon is from Watinuma Community on the Anangu Pitjantjatjara/ Yankunytjatjara Lands, 350km SE of ULURU. Originally she was from the north of Watarru around Aralya and Kunytjanu. Like many people of her era Manyitjanu was born in the desert when her family were walking around, living a traditional nomadic life. After ceremony time, and as an early school age girl, her aunties took her from Watarru back to Ernabella. She later returned to Pipalyatjara with Winifred Hilliard many years later when they were helping people out west, taking them clothes and food. She also learnt numerous arts and crafts such as making moccasins and cushions out of kangaroo skins, spinning and dying wool, batik tie dying and wool carving (punu) at the Ernabella Arts Centre. Currently she is involved in basket weaving and painting on canvas. She married and moved to Fregon when it was established in 1961. She was involved in the Fregon Choir, helped set up he Fregon Craft room, as well as the Fregon School with Nancy Sheppard. She has five children and four grandchildren. Maryjane has recently returned to the arts centre to paint the stories from her country including the Seven Sisters and Mamungari’nya, she also paints landscapes from around Aralya and Kunytjanu. Her style is quite unique, characterised by bold and energetic use of colour. Art Prizes 2017 Wynne Prize finalist 7 Short St, PO Box 1550 , Broome Western Australia 6725 p: 08 9192 6116 / 08 9192 2658 e: [email protected] www.shortstgallery.com Group Exhibitions 2018 Minymaku Walka - (The Mark of Women) 2018 Short Street Gallery Broome, Western Australia. -

Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Park Visitor Guide

VISITOR GUIDE Palya! Welcome to Anangu land Uluru–Kata Tjuta National Park Uluru–Kata Tjuta paRK PASSES 3 DAY per adult $25.00 National Park is ANNUAL per adult $32.50 Aboriginal land. NT ANNUAL VEHICLE NT residents $65.00 The park is jointly Children under 16 free managed by its Anangu traditional owners and PARK OPENING HOURS Parks Australia. The park MONTH OPEN CLOSE The park closes overnight is recognised by UNESCO There is no camping in the park as a World Heritage Area Dec, Jan, Feb 5.00 am 9.00 pm Camping available at the resort for both its natural and March 5.30 am 8.30 pm cultural values. April 5.30 am 8.00 pm PLAN YOUR DAYS 6.00 am 7.30 pm FRONT COVER: Kunmanara May Toilets provided at: Taylor (see page 7 for a detailed June, July 6.30 am 7.30 pm • Cultural Centre explanation of this painting) Aug 6.00 am 7.30 pm Photo: Steve Strike • Mala carpark Sept 5.30 am 7.30 pm • Talinguru Nyakunytjaku ISBN 064253 7874 February 2013 Oct 5.00 am 8.00 pm • Kata Tjuta Sunset Viewing Unless otherwise indicated Nov 5.00 am 8.30 pm copyright in this guide, including photographs, is vested in the CULTURAL CENTRE HOURS 7.00 am–6.00 pm Department of Sustainability, Information desk 8.00 am–5.00 pm Environment, Water, Population and Communities. Cultural or environmental presentation • Monday to Friday 10.00 am Originally designed by In Graphic Detail. FREE RANGER-GUIDED MALA walk 8.00 am Printed by Colemans Printing, Darwin using Elemental Chlorine • Allow 1.5 - 2 hours Free (ECF) Paper from Sustainable • Meet at Mala carpark Forests. -

Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Park Tourism Directions: Stage 1 September 2010 Ovember 2008

Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Park Tourism Directions: Stage 1 September 2010 ovember 2008 Uluru Tourism Directions V4.indd1 1 9/09/2010 10:44:02 AM Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Park Tourism Directions: Stage 1 Foreword In 2010 Anangu will celebrate the 25th anniversary of the handback of Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Park. Over this time we have seen many visitors come to enjoy the park and learn about the cultural importance of this place. Many visitors have gone away knowing a little about Tjukurpa and Anangu connection to the land. Over the next 25 years the Anangu voice in tourism will become even stronger. Anangu will be working very closely with the tourism industry and working hard on developing our own tourism initiatives for the park. Tourism Directions: Stage 1 represents a turning point for tourism in the park. It shows that we Anangu are developing pathways for our children to have a strong future. And above all, it demonstrates that Tjukurpa will be heard in all aspects of tourism and that our culture will be promoted to the next generation visiting our country. Harry Wilson Chair, Uluru-Kata Tjuta Board of Management Introduction Ananguku ngura nyangatja ka pukulpa pitjama. Nyakula munu nintiringkula Anangu kulintjikitjangku munu kulinma Ananguku ara kunpu munu pulka mulapa ngaranyi. Nganana malikitja tjutaku mukuringanyi nganampa ngura nintiringkunytjikitja munu Anangu kulintjikitja. Kuwari malikitja tjuta tjintu tjarpantjala nyakula kutju munu puli tatilpai. Puli nyangatja miil-miilpa alatjitu. Uti nyura tatintja wiya! Tatintjala ara mulapa wiya. © Tony Tjamiwa This is Anangu land and we welcome you. Look around and learn so that you can know something about Anangu and understand that Anangu culture is strong and really important. -

Living & Working Information

LONGITUDE 131° LIVING & WORKING INFORMATION ESSENTIAL INFORMATION BAILLIE LODGES Baillie Lodges is a collection of three intimate luxury lodges offering unique Australian experiences. Spectacular locations combined with contemporary design, exceptional cuisine, first name service, all-inclusive tariffs and indulgent surrounds combine to deliver sophisticated and exclusive encounters with luxe appeal. Longitude 131° at Uluru-Kata Tjuta is the ultimate outback luxury experience. Southern Ocean Lodge on Kangaroo Island is globally celebrated and acclaimed. Capella Lodge on Lord Howe Island launched the portfolio and continues to capture guests in its magic. Baillie Lodges is a founding member of Luxury Lodges of Australia. LOCATION Longitude 131° (L131) overlooks Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Park in the Northern Territory, 450km south west of Alice Springs. The lodge is approximately 15km from Uluru (Ayers Rock) and 5km from Ayers Rock Resort and the township of Yulara. CLIMATE Uluru has a dry, arid atmosphere with daytime temperatures varying from a hot 45°C in the summer months (December-March) to a cool 19°C in the winter months. Nights can be chilly, with temperatures as low as -2°C in winter. SUSTAINABILITY Baillie Lodges is committed to minimising our environmental footprint. Each of the guest tents has been carefully designed to have minimal impact on the delicate natural environment, standing lightly upon red sand dunes. Solar panels on each tent provide hot water heating, whilst a major solar installation at Ayers Rock Resort generates about 15 per cent of Yulara’s average energy use, reducing the reliance on fossil fuels. Other initiatives include separation of recyclable goods, the use of recycled water for gardens, using food compost from the kitchen on garden beds and growing a selection of fresh produce onsite to lesson our carbon footprint. -

World Heritage Site 1

World Heritage Site 1 This site is managed by both the national government of this country in the southern hemisphere and the native people who have lived here for thousands of years. Tidal plains, lowlands, plateaus, floodplains, rare species and ancient archaeological areas characterize this diverse site. Photograph by Sam Abell Photograph by Sam OCEANIA World Heritage Site 2 This natural marvel can be seen from space and is the world’s biggest single structure made by living organisms–coral! A biological hotspot, it is home to over 2,000 species of fish, coral, birds, and reptiles. The reef is under threat of climate change including rising air and water temperatures, which can result in a process known as coral bleaching. Overfishing has also led to an overabundance of coral’s predators. Satellite image courtesy NASA OCEANIA World Heritage Site 3 This more modern example of a World Heritage Site was completed in 1973, after 16 years of construction. The performance venue’s creative design and innovative use of engineering make it one of the greatest architectural achievements of the 20th century. Photograph by David Dudley, MyShot OCEANIA World Heritage Site 4 The archaeological remains of this Pacific island site provide information about the progression of agricultural practices over approximately 7,000-10,000 years. The site contains evidence of several technological innovations in farming and chronological information about when these advances occurred. Photograph by Daryl Lacey, MyShot OCEANIA World Heritage Site 5 The expansive protected area on these South Pacific islands contains unique animal and plant habitats on both land and sea. -

Uluru Handback

Episode 30 Teacher Resource 27th October 2015 Uluru Handback Students will develop an understanding of 1. In pairs, discuss the Uluru Handback story and record the main the handback of Uluru to the Anangu people and their deep connection to the points of your discussion. place. They will also investigate the issue 2. Which Aboriginal Group are the traditional owners of Uluru of allowing people to climb Uluru. a. Anangu b. Noongar c. Yolngu 3. Why is Uluru a sacred place for them? 4. What did European settlers call Uluru? 5. What significant event happened on October 26 1985? Science – Year 4 6. What did the handback officially recognise? Earth’s surface changes over time as a 7. Who do the traditional owners share the running of Uluru-Kata result of natural processes and human Tjuta National Park with? activity (ACSSU075) 8. Why has the relationship between Indigenous and non- Science knowledge helps people to Indigenous Australians been tense? understand the effect of their actions (ACSHE062) 9. Do you think tourists should be allowed to climb Uluru? Explain your answer. History – Year 4 10. How did this story make you feel? The diversity of Australia's first peoples and the long and continuous connection of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples to Country/ Place (land, sea, waterways and skies) and the implications for their daily lives. (ACHHK077) Brainstorm Discuss the BtN Uluru Handback story as a class. Ask students the Geography – Year 8 following questions: The aesthetic, cultural and spiritual value of landscapes and landforms for people, including Aboriginal and Torres Strait • What do you know about Uluru? Islander Peoples (ACHGK049) • What was Uluru once called? • How would you describe Uluru? The different types of landscapes and their distinctive landform features (ACHGK048) • Uluru is often called a `national icon’. -

Go Jetters Continent of Oceania

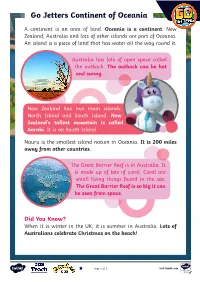

Go Jetters Continent of Oceania A continent is an area of land. Oceania is a continent. New Zealand, Australia and lots of other islands are part of Oceania. An island is a piece of land that has water all the way round it. Australia has lots of open space called the outback. The outback can be hot and sunny. New Zealand has two main islands: North Island and South Island. New Zealand’s tallest mountain is called Aoraki. It is on South Island. Nauru is the smallest island nation in Oceania. It is 200 miles away from other countries. The Great Barrier Reef is in Australia. It is made up of lots of coral. Coral are small living things found in the sea. The Great Barrier Reef is so big it can be seen from space. Did You Know? When it is winter in the UK, it is summer in Australia. Lots of Australians celebrate Christmas on the beach! Page 1 of 2 visit twinkl.com Go Jetters Continent of Oceania 1. Which of these countries are in Oceania? Tick two. Italy Australia New Zealand 2. What are the names of the two islands in New Zealand? Tick two. West Island North Island South Island 3. What is the smallest island nation in Oceania? Tick one. Nauru New Zealand Australia 4. What is it like in the outback? Tick one. hot and sunny wet and warm cold and snowy 5. What are coral? Tick one. flowers plants small living things Page 2 of 2 visit twinkl.com Go Jetters Continent of Oceania Answers 1. -

Outback Australia: the Colour of Red CRUA

5 Days Outback Australia: The Colour of Red CRUA Outback Australia: The Colour of Red Journey to the Red Centre of Australia – the sacred landscapes of the Outback and imposing Uluru. Delve into fascinating rituals of the Anangu during your Inspiring Journey through outback Australia and share in their spiritual connection with this ancient land that spans millennia. Uluru 5 DAYS Uluru • Kata Tjuta • Kings Canyon • West MacDonnell Ranges • Alice Springs Discover Iconic Uluru (Ayers Rock) Embark on a 4WD off the Mereenie Loop Road Wander through Simpsons Gap Explore The 36 mystical domes of Kata Tjuta (the Olgas) Simpsons Gap Fascinating Angkerle (Standley Chasm) Immerse Hike through Walpa Gorge Learn about Uluru’s sacred sites Hike to the top of Kings Canyon for magnificent views Relax Toast an Uluru sunset with sparkling wine Experience a spectacular Red Centre sunrise Unwind in your Deluxe Spa Room at Kings Canyon Resort Uluru Base Walk 5 Days Outback Australia: The Colour of Red CRUA At a glance: TOP 3 HIGHLIGHTS 1. Barbecue dinner around a campfire under the Milky Way 2. Embark on Kings Canyon’s 6km rim walk West MacDonnell Ranges Angkerle 3. Witness the spectacular changing Alice 2 Springs colours as the sun sets over Uluru Mereenie Simpsons Ellery Creek Loop Gap Big Hole DINING Kings Canyon 1 4 Full buffet breakfasts Kings Creek 3 Lunches Station 2 Dinners with wine Ayers Rock Resort 2 Local Dining Experiences Curtin Springs 1 Station Kata Tjuta Uluru Uluru–Kata Tjuta National Park l Start l Finish l Overnight l Sightseeing Kata -

CONTINUING OUR STORY Kaltjiti Arts Is Proud to Present

CONTINUING OUR STORY Kaltjiti Arts is proud to present: CONTINUING OUR STORY Kaltjiti Arts is a community-based art centre located in the Kaltjiti Community at Fregon on the Anangu Pitjantjatjara Yankunytjatjara (APY) Lands in the far north of South Australia. It was established in 1961 as an outstation of the Ernabella mission and focuses on artistic excellence, cultural maintenance and promotes economic sustainability through the arts. Paul Johnstone Gallery is very proud to continue representing the extraordinary talent of Kaltjiti Artists. Exhibition opens Friday 9 June and concludes 25 June 2017 Image front cover: Taylor Cooper and his grand nephew Daryl 2/2 Harriet Place Darwin NT 0800 / T: +61 8 8941 2220 Gallery hours: Tuesday - Friday 10-2pm & Saturday 10-2pm email: [email protected] www.pauljohnstonegallery.com.au Senior Women’s Collaborative (10989) acrylic on linen 200 x 200cm $9250 CAROLANNE KEN Date of birth: 1971 Location: Fregon Language group(s): Pitjantjatjara/Yankunytjatjara Carolanne Ken is from Fregon on the Anangu Pitjantjatjara Yankunytjatjara Lands, 350m south east of Uluru. Her father’s country is Mulya Ulpa, near Pilkinga, on the road from Makari to Iltur and her mother’s country is Walytjitjata, west of Kanypi. Carolanne paints Minyma Maluli, which was passed down from her maternal grandmother. Born in 1971, Carolanne went to school in Fregon and Woodville High in Adelaide, graduating in 1986. She has worked at Fregon Anangu School, ANTEP and Kaltjiti Arts. Carolanne began painting at Kaltjiti Arts in 2004. She assists with the studio management at Kaltjiti Arts, and is now painting fulltime.