Download Full Article 303.2KB .Pdf File

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Driving Holidays in the Northern Territory the Northern Territory Is the Ultimate Drive Holiday Destination

Driving holidays in the Northern Territory The Northern Territory is the ultimate drive holiday destination A driving holiday is one of the best ways to see the Northern Territory. Whether you are a keen adventurer longing for open road or you just want to take your time and tick off some of those bucket list items – the NT has something for everyone. Top things to include on a drive holiday to the NT Discover rich Aboriginal cultural experiences Try tantalizing local produce Contents and bush tucker infused cuisine Swim in outback waterholes and explore incredible waterfalls Short Drives (2 - 5 days) Check out one of the many quirky NT events A Waterfall hopping around Litchfield National Park 6 Follow one of the unique B Kakadu National Park Explorer 8 art trails in the NT C Visit Katherine and Nitmiluk National Park 10 Immerse in the extensive military D Alice Springs Explorer 12 history of the NT E Uluru and Kings Canyon Highlights 14 F Uluru and Kings Canyon – Red Centre Way 16 Long Drives (6+ days) G Victoria River region – Savannah Way 20 H Kakadu and Katherine – Nature’s Way 22 I Katherine and Arnhem – Arnhem Way 24 J Alice Springs, Tennant Creek and Katherine regions – Binns Track 26 K Alice Springs to Darwin – Explorers Way 28 Parks and reserves facilities and activities 32 Festivals and Events 2020 36 2 Sealed road Garig Gunak Barlu Unsealed road National Park 4WD road (Permit required) Tiwi Islands ARAFURA SEA Melville Island Bathurst VAN DIEMEN Cobourg Island Peninsula GULF Maningrida BEAGLE GULF Djukbinj National Park Milingimbi -

GREAT ARTESIAN BASIN Responsibility to Any Person Using the Information Or Advice Contained Herein

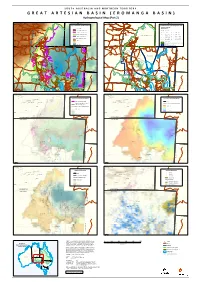

S O U T H A U S T R A L I A A N D N O R T H E R N T E R R I T O R Y G R E A T A R T E S I A N B A S I N ( E RNturiyNaturiyaO M A N G A B A S I N ) Pmara JutPumntaara Jutunta YuenduYmuuendumuYuelamu " " Y"uelamu Hydrogeological Map (Part " 2) Nyirri"pi " " Papunya Papunya ! Mount Liebig " Mount Liebig " " " Haasts Bluff Haasts Bluff ! " Ground Elevation & Aquifer Conditions " Groundwater Salinity & Management Zones ! ! !! GAB Wells and Springs Amoonguna ! Amoonguna " GAB Spring " ! ! ! Salinity (μ S/cm) Hermannsburg Hermannsburg ! " " ! Areyonga GAB Spring Exclusion Zone Areyonga ! Well D Spring " Wallace Rockhole Santa Teresa " Wallace Rockhole Santa Teresa " " " " Extent of Saturated Aquifer ! D 1 - 500 ! D 5001 - 7000 Extent of Confined Aquifer ! D 501 - 1000 ! D 7001 - 10000 Titjikala Titjikala " " NT GAB Management Zone ! D ! Extent of Artesian Water 1001 - 1500 D 10001 - 25000 ! D ! Land Surface Elevation (m AHD) 1501 - 2000 D 25001 - 50000 Imanpa Imanpa ! " " ! ! D 2001 - 3000 ! ! 50001 - 100000 High : 1515 ! Mutitjulu Mutitjulu ! ! D " " ! 3001 - 5000 ! ! ! Finke Finke ! ! ! " !"!!! ! Northern Territory GAB Water Control District ! ! ! Low : -15 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! FNWAP Management Zone NORTHERN TERRITORY Birdsville NORTHERN TERRITORY ! ! ! Birdsville " ! ! ! " ! ! SOUTH AUSTRALIA SOUTH AUSTRALIA ! ! ! ! ! ! !!!!!!! !!!! D !! D !!! DD ! DD ! !D ! ! DD !! D !! !D !! D !! D ! D ! D ! D ! D ! !! D ! D ! D ! D ! DDDD ! Western D !! ! ! ! ! Recharge Zone ! ! ! ! ! ! D D ! ! ! ! ! ! N N ! ! A A ! L L ! ! ! ! S S ! ! N N ! ! Western Zone E -

Centring Anangu Voices

Report NR005 2017 Centring Anangu Voices A research project exploring how Nyangatjatjara College might better strengthen Anangu aspirations through education Sam Osborne John Guenther Lorraine King Karina Lester Sandra Ken Rose Lester Cen Centring Anangu Voices A research project exploring how Nyangatjatjara College might better strengthen Anangu aspirations through education. December 2017 Research conducted by Ninti One Ltd in conjunction with Nyangatjatjara College Dr Sam Osborne, Dr John Guenther, Lorraine King, Karina Lester, Sandra Ken, Rose Lester 1 Executive Summary Since 2011, Nyangatjatjara College has conducted a series of student and community interviews aimed at providing feedback to the school regarding student experiences and their future aspirations. These narratives have developed significantly over the last seven years and this study, a broader research piece, highlights a shift from expressions of social and economic uncertainty to narratives that are more explicit in articulating clear directions for the future. These include: • A strong expectation that education should engage young people in training and work experiences as a pathway to employment in the community • Strong and consistent articulation of the importance of intergenerational engagement to 1. Ground young people in their stories, identity, language and culture 2. Encourage young people to remain focussed on positive and productive pathways through mentoring 3. Prepare young people for work in fields such as ranger work and cultural tourism • Utilise a three community approach to semi-residential boarding using the Yulara facilities to provide access to expert instruction through intensive delivery models • Metropolitan boarding programs have realised patchy outcomes for students and families. The benefits of these experiences need to be built on through realistic planning for students who inevitably return (between 3 weeks and 18 months from commencement). -

Appendix a (PDF 85KB)

A Appendix A: Committee visits to remote Aboriginal and Torres Strait communities As part of the Committee’s inquiry into remote Indigenous community stores the Committee visited seventeen communities, all of which had a distinctive culture, history and identity. The Committee began its community visits on 30 March 2009 travelling to the Torres Strait and the Cape York Peninsula in Queensland over four days. In late April the Committee visited communities in Central Australia over a three day period. Final consultations were held in Broome, Darwin and various remote regions in the Northern Territory including North West Arnhem Land. These visits took place in July over a five day period. At each location the Committee held a public meeting followed by an open forum. These meetings demonstrated to the Committee the importance of the store in remote community life. The Committee appreciated the generous hospitality and evidence provided to the Committee by traditional owners and elders, clans and families in all the remote Aboriginal and Torres Strait communities visited during the inquiry. The Committee would also like to thank everyone who assisted with the administrative organisation of the Committee’s community visits including ICC managers, Torres Strait Councils, Government Business Managers and many others within the communities. A brief synopsis of each community visit is set out below.1 1 Where population figures are given, these are taken from a range of sources including 2006 Census data and Grants Commission figures. 158 EVERYBODY’S BUSINESS Torres Strait Islands The Torres Strait Islands (TSI), traditionally called Zenadth Kes, comprise 274 small islands in an area of 48 000 square kilometres (kms), from the tip of Cape York north to Papua New Guinea and Indonesia. -

CENTRAL LAND COUNCIL Submission to the Independent

CENTRAL LAND COUNCIL Submission to the Independent Reviewer Independent Review of the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act (Cth) 1999 16 April 2020 HEAD OFFICE 27 Stuart Hwy, Alice Springs POST PO Box 3321 Alice Springs NT 0871 1 PHONE (08) 8951 6211 FAX (08) 8953 4343 WEB www.clc.org.au ABN 71979 619 0393 ALPARRA (08) 8956 9955 HARTS RANGE (08) 8956 9555 KALKARINGI (08) 8975 0885 MUTITJULU (08) 5956 2119 PAPUNYA (08) 8956 8658 TENNANT CREEK (08) 8962 2343 YUENDUMU (08) 8956 4118 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. SUMMARY OF RECOMMENDATIONS ....................................................................... 3 2. ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS .......................................................................... 4 3. OVERVIEW ...................................................................................................................... 5 4. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................. 5 5. MODERNISING CONSULTATION AND INPUT ......................................................... 7 5.1. Consultation processes ................................................................................................... 8 5.2. Consultation timing ........................................................................................................ 9 5.3. Permits to take or impact listed threatened species or communities ........................... 10 6. CULTURAL HERITAGE AND SITE PROTECTION .................................................. 11 7. BILATERAL -

The Debilitating Aftermath of 10 Years of NT Intervention

18 Land Rights News • Northern Edition July 2017 • www.nlc.org.au The debilitating aftermath of 10 years of NT Intervention Jon Altman* n the April issue of Land Rights News I This is of special concern to Indigenous I do this because the Intervention was Both communities were established by celebrated the 30th anniversary of the people in the Northern Territory if the heavily promoted as a major project of the Commonwealth in 1959 and 1957 progressive and supportive Blanchard Commonwealth’s constitutional territory improvement and modernisation. Who can respectively and were colloquially referred report Return to Country: the Aboriginal powers remain in place and if, as in 2007, forget Malcolm Brough’s heroic call to to as ‘the Jewel of the Centre’ and ‘the Homelands Movement in Australia. And racial discrimination laws can be suspended ‘Stabilise, Normalise and Exit’ remote NT Jewel of the North’: these were to be the I wondered what celebration or reproach at the whim of the government of the day. communities, the delivery of what can be two demonstration communities where the the 10th anniversary of the Northern thought of as a domestic ‘Marshall Plan’ to Welfare Branch was going to show to all Third are the views expressed by Territory National Emergency Response, demonstrate the developmental powers of how modernisation and development could Indigenous community leaders who are the Intervention that was militaristically the Australian government in a jurisdiction and should be delivered. also subjects of the Intervention, several launched with extraordinary media fanfare where owing to a quirk of the Australian whom I heard present views in two events In 1972 when policy shifted to self- on 21 June 2007 might elicit. -

Submission to the Northern Territory Suicide Prevention Strategic Review

Central Australian Aboriginal Congress 30 July 2017 Central Australian Aboriginal Congress Submission to the Northern Territory Suicide Prevention Strategic Review 30 July 2017 Submitted by: Donna Ah Chee Chief Executive Officer Central Australian Aboriginal Congress Aboriginal Corporation PO Box 1604, Alice Springs NT 0871 T: 08 89514401 E: [email protected] 1 Central Australian Aboriginal Congress 30 July 2017 Executive summary The Central Australian Aboriginal Congress (Congress) is the largest Aboriginal community-controlled health service (ACCHS) in the Northern Territory, providing a comprehensive, holistic and culturally- appropriate primary health care service to more than 14 000 Aboriginal people living in and nearby Alice Springs each year as well as the remote communities of Ltyentye Apurte (Santa Teresa), Ntaria (Hermannsburg) and Wallace Rockhole, Utju (Areyonga), Mutitjulu and Amoonguna. The suicide rate for Aboriginal Australians is almost twice the rate for non-Aboriginal Australians (AIHW, 2016). This submission to the Northern Territory Government’s development of a Suicide Prevention Strategic Plan addresses suicide prevention from a social determinants, population health and primary prevention perspective, as well as from a mental health service delivery perspective. Particular attention is given to young Aboriginal people who have highest national rates of suicide, which can be largely attributed to unhealthy early childhood development, linked to disadvantage. Key issues raised in this submission are: . That suicide in Aboriginal communities is fundamentally linked to disempowerment, disadvantage and the social determinants of health. Unhealthy brain development, self-regulation and coping skills in early childhood are linked to suicide. This is a key issue for young Aboriginal people who are falling well behind in the Australian Early Development Census (AEDC) by age 5. -

Periodic Report on the State of Conservation of Uluru-Kata Tjuta

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL PERIODIC REPORT SECTION II Report on the State of Conservation of Uluru – Kata Tjuta National Park ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ Periodic Report 2002 - Section II Uluru - Kata Tjuta National Park 1 ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- II.1. INTRODUCTION a. State Party Australia b. Name of World Heritage property Uluru - Kata Tjuta National Park c. Geographical coordinates to the nearest second Uluru - Kata Tjuta National Park is located in Central Australia, in the south-western corner of the Northern Territory, at latitude 25°05’ - 25°25’ south and longitude 130°40’ - 131° east. d. Date of inscription on the World Heritage List Uluru - Kata Tjuta National Park was nominated and inscribed on the World Heritage List for natural values in 1987 under natural criteria (ii) and (iii). Uluru - Kata Tjuta National Park was renominated and inscribed on the World Heritage List as a Cultural Landscape in 1994 under cultural criteria (v) and (vi). e. Organization(s) or entity(ies) responsible for the preparation of the report This report was prepared by Parks Australia, in association with the Heritage Management Branch of the Department of the Environment and Heritage. II.2. STATEMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE Criteria Uluru - Kata Tjuta -

Submission To

Central Australian Aboriginal Congress submission to: the Productivity Commission’s Inquiry into the Social and Economic Benefits of Improving Mental Health About Congress Central Australian Aboriginal Congress (Congress) is the largest Aboriginal community-controlled health service (ACCHS) in the Northern Territory, providing a comprehensive, holistic and culturally-appropriate primary health care service to more than 14 000 Aboriginal people living in Alice Springs each year as well as the remote communities of Ltyentye Apurte (Santa Teresa), Ntaria (Hermannsburg) and Wallace Rockhole, Utju (Areyonga), Mutitjulu and Amoonguna. Congress operates within a comprehensive primary health care (CPHC) framework, providing a range of services in remote areas of Central Australia. Alongside general practice, services and programs on issues such as alcohol, tobacco and other drugs; early childhood development and family support; and mental health and social and emotional well-being are also provided. We also advocate for those social determinants of health (both physical and mental) including education, housing and justice. About this submission Congress has written a number of submissions relevant to the terms of reference of the inquiry. They include addressing the factors that are fundamental to good health and economic and social participation, as well as mental health services. The main arguments and recommendations are outlined below, along with links to the related submissions which are clearly referenced with research evidence and data to support our reasoning. To view the full suite of our submissions, please see https://www.caac.org.au/aboriginal-health/policy-submissions-publications. Determinants of good mental health and participation Poor mental health is heavily associated with social inequality and disempowerment, which includes the specific historical and contemporary issues experienced by Aboriginal peoples. -

Outback Australia - the Colour of Red

Outback Australia - The Colour of Red Your itinerary Start Location Visited Location Plane End Location Cruise Train Over night Ferry Day 1 healing. The flickering glow of this evening's fire, dancing under the canopy of a Arrive Ayers Rock (2 Nights) starry Southern Hemisphere sky, is the perfect accompaniment to your Regional 'Under a Desert Moon' Meal. This degustation menu with matching wines is the Feel the stirring of something bigger than you as you arrive in Ayers Rock Resort perfect end to the day. Sit back and listen to the sounds of the outback come alive (flights to arrive prior to 2pm), only 20 km from magical, mystical Uluru and the at night in the company of new friends. launchpad to Australia's spiritual heart in the Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Park. This afternoon, you'll travel to Uluru as the day fades away, the outback sun bidding a Hotel - Kings Canyon Resort, Deluxe Spa Rooms fiery farewell. Uluru towers over the Northern Territory's remote landscape, the perfect backdrop for this evening's Welcome Reception. Included Meals - Breakfast, Lunch, Regional Dinner Day 4 Hotel - Sails in the Desert, Ayers Rock Resort Kings Canyon - Alice Springs Included Meals - Welcome Reception Gaze across the deep chasm at the edge of Kings Canyon as you embark on the Day 2 spellbinding 6 km sunrise Rim Walk, past the sandstone domes of the 'Lost City' Uluru Sightseeing and down the stairs to the lush 'Garden of Eden'. Or you can opt for a gentler stroll along the canyon creek bed, treading in the footsteps of the Luritja people Wake early, taking time to pause and contemplate the mesmerising sunrise over who once found sanctuary amidst the Itara trees at the base of the canyon. -

Manyitjanu Lennon

Manyitjanu Lennon Born c. 1940 Language Group Pitjantjatjara Region APY Lands Biography Manyitjanu Lennon is from Watinuma Community on the Anangu Pitjantjatjara/ Yankunytjatjara Lands, 350km SE of ULURU. Originally she was from the north of Watarru around Aralya and Kunytjanu. Like many people of her era Manyitjanu was born in the desert when her family were walking around, living a traditional nomadic life. After ceremony time, and as an early school age girl, her aunties took her from Watarru back to Ernabella. She later returned to Pipalyatjara with Winifred Hilliard many years later when they were helping people out west, taking them clothes and food. She also learnt numerous arts and crafts such as making moccasins and cushions out of kangaroo skins, spinning and dying wool, batik tie dying and wool carving (punu) at the Ernabella Arts Centre. Currently she is involved in basket weaving and painting on canvas. She married and moved to Fregon when it was established in 1961. She was involved in the Fregon Choir, helped set up he Fregon Craft room, as well as the Fregon School with Nancy Sheppard. She has five children and four grandchildren. Maryjane has recently returned to the arts centre to paint the stories from her country including the Seven Sisters and Mamungari’nya, she also paints landscapes from around Aralya and Kunytjanu. Her style is quite unique, characterised by bold and energetic use of colour. Art Prizes 2017 Wynne Prize finalist 7 Short St, PO Box 1550 , Broome Western Australia 6725 p: 08 9192 6116 / 08 9192 2658 e: [email protected] www.shortstgallery.com Group Exhibitions 2018 Minymaku Walka - (The Mark of Women) 2018 Short Street Gallery Broome, Western Australia. -

The Uluru Statement: a First Nations Perspective of the Implications for Social Reconstructive Race Relations in Australia

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Research Online @ ECU Edith Cowan University Research Online ECU Publications Post 2013 2019 The Uluru statement: A First Nations perspective of the implications for social reconstructive race relations in Australia Jesse John Fleay Edith Cowan University, [email protected] Barry Judd Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.ecu.edu.au/ecuworkspost2013 Part of the Australian Studies Commons, and the Indigenous Studies Commons 10.5204/ijcis.v12i1.532 Fleay, J., & Judd, B. (2019). The Uluru statement. International Journal of Critical Indigenous Studies, 11(1). Available here. This Journal Article is posted at Research Online. https://ro.ecu.edu.au/ecuworkspost2013/5732 1 International Journal of Critical Indigenous Studies Volume 12, Number 1, 2019 The Uluru Statement: A First Nation’s perspective of the implications for social reconstructive race relations in Australia Authors Jesse John Fleay Barry Judd About the authors Mr Jesse J. Fleay descends from the Balladong Noongar people in the south-west of Western Australia, and the Nukunu people of coastal South Australia. He is an Australian civil rights campaigner based at Kurongkurl Katitjin, Edith Cowan University’s Centre for Indigenous Australian Education and Research, in Western Australia. His interests include social justice, health and education. Mr Fleay was one of the elected delegates to both the Perth and National Dialogues of the Referendum Council, established to advise the Prime Minister and Leader of the Opposition on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander rights though a constitutional amendment. He now works on the referendum campaign, elected as youth representative to the Uluru Work Group.