UNRWA Photographs 1950-1978: a View on History Or Shaped by History? Stephanie Latte Abdallah

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Campscapes': Palestinian Refugee Camps and Informal Settlements In

Political Geography 44 (2015) 9e18 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Political Geography journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/polgeo From spaces of exception to ‘campscapes’: Palestinian refugee camps and informal settlements in Beirut * Diana Martin Department of Psychology, Stellenbosch University, Wilcocks Building, Ryneveld Street, Stellenbosch, 7600, South Africa article info abstract Article history: The recent literature on the refugee condition and spaces has heavily drawn on Agamben's reflection on Available online 16 October 2014 ‘bare life’ and the ‘camp’. As refugees are cast out the normal juridical order, their lives are confined to refugee camps, biopolitical spaces that allow for the separation of the alien from the nation. But is the Keywords: camp the only spatial device that separates qualified and expendable lives? What happens when the Space of exception space of the camp overlaps with the space of the city? Taking the Palestinian refugee camp of Shatila in Refugee camp Beirut as a case, this study problematises the utilisation of legal prisms and clear-cut distinctions for the Informal settlements understanding of the production of bare life and spaces of exception. Isolated at the time of its estab- Palestinian refugees ‘ ’ fl Lebanon lishment, Shatila is today part of the so-called misery belt . Physical continuities are also re ected by the distribution of the population as both Palestinians and non-Palestinians, including Lebanese, live in Shatila and the surrounding informal settlements. As physical and symbolic boundaries separating the refugee and the citizen blur, I argue that the exception is not only produced through law and its sus- pension. -

The Making of a Leftist Milieu: Anti-Colonialism, Anti-Fascism, and the Political Engagement of Intellectuals in Mandate Lebanon, 1920- 1948

THE MAKING OF A LEFTIST MILIEU: ANTI-COLONIALISM, ANTI-FASCISM, AND THE POLITICAL ENGAGEMENT OF INTELLECTUALS IN MANDATE LEBANON, 1920- 1948. A dissertation presented By Sana Tannoury Karam to The Department of History In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy In the field of History Northeastern University Boston, Massachusetts December 2017 1 THE MAKING OF A LEFTIST MILIEU: ANTI-COLONIALISM, ANTI-FASCISM, AND THE POLITICAL ENGAGEMENT OF INTELLECTUALS IN MANDATE LEBANON, 1920- 1948. A dissertation presented By Sana Tannoury Karam ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History in the College of Social Sciences and Humanities of Northeastern University December 2017 2 This dissertation is an intellectual and cultural history of an invisible generation of leftists that were active in Lebanon, and more generally in the Levant, between the years 1920 and 1948. It chronicles the foundation and development of this intellectual milieu within the political Left, and how intellectuals interpreted leftist principles and struggled to maintain a fluid, ideologically non-rigid space, in which they incorporated an array of ideas and affinities, and formulated their own distinct worldviews. More broadly, this study is concerned with how intellectuals in the post-World War One period engaged with the political sphere and negotiated their presence within new structures of power. It explains the social, political, as well as personal contexts that prompted intellectuals embrace certain ideas. Using periodicals, personal papers, memoirs, and collections of primary material produced by this milieu, this dissertation argues that leftist intellectuals pushed to politicize the role and figure of the ‘intellectual’. -

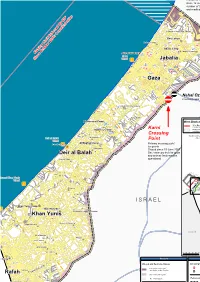

Gaza Strip Closure Map , December 2007

UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs Access and Closure - Gaza Strip December 2007 s rd t: o i t c im n N c L e o Erez A . m F g m t i lo n . i s s i n m h Crossing Point h t: in O s 0 m i s g i 2 o le F im i A Primary crossing for people (workers C L m re i l a and traders) and humanitarian personnel in g a rt in c Closed for Palestinian workers e h ti s u since 12 March 2006 B i a 2 F Closed for Palestinians 0 n 0 2 since 12 June 2007 except for a limited 2 1 number of traders, humanitarian workers and medical cases s F le D i I m y l B a d ic e t c u r a Al Qaraya al Badawiya al Maslakh ¯p fo n P Ç 6 n : ¬ E 6 it 0 Beit Lahiya 0 im 2 P L r Madinat al 'Awda e P ¯p "p ¯p "p g b Beit Hanoun in o ¯p ¯p ¯p ¯p h t Jabalia Camp ¯p ¯p ¯p P ¯p s c p ¯p ¯p i p"p ¯¯p "pP 'Izbat Beit HanounP F O Ash Shati' Camp ¯p " ¯p e "p "p ¯p ¯p c Gaza ¯Pp ¯p "p n p i t ¯ Wharf S Jabalia S t !x id ¯p S h s a a "p m R ¯p¯p¯p ¯p a l- ¯p p r A ¯p ¯ a "p K "p ¯p l- ¯p "p E ¯p"p ¯p¯p"p ¯p¯p ¯p Gaza ¯p ¯p ¯p ¯p t S ¯p a m ¯p¯p ¯p ra a K l- Ç A ¬ Nahal Oz ¯p ¬Ç Crossing point for solid and liquid fuels p t ¯ t S fa ¯p Al Mughraqa (Abu Middein) ra P r A e as Y Juhor ad Dik ¯pP ¯p LEBANON An Nuseirat Camp ¯p ¯p West Bank and Gaza Strip P¯p ¯p ¯p West Bank Barrier (constructed and planned) ¯p ¯p ¯p Al Bureij Camp¯p ¯p Karni Areas inaccessible to Palestinians or subject to restrictions ¯p¯pP¯p Crossing `Akko !P MEDITERRANEAN Az Zawayda !P Deir al Balah ¯p P Point SEA Haifa Tiberias !P Wharf Nazareth !P ¯p Al Maghazi Camp¯p¯p Deir al Balah Camp Primary -

The Lebanon Country of Origin Information Report July 2006

COUNTRY OF ORIGIN INFORMATION REPORT THE LEBANON JULY 2006 RDS-IND COUNTRY OF ORIGIN INFORMATION SERVICE JULY 2006 THE LEBANON Contents 1. SCOPE OF DOCUMENT................................................................................1.01 2. GEOGRAPHY ..............................................................................................2.01 Map of Lebanon........................................................................................2.04 3. ECONOMY ..................................................................................................3.01 4. HISTORY ....................................................................................................4.01 1975 – 2005: Civil war; Israeli occupations; Syrian occupation.........4.01 Syrian withdrawal: April – May 2005.....................................................4.06 Elections: May – June 2005 ...................................................................4.09 Other recent events: 2005-2006.............................................................4.12 5. STATE STRUCTURES ..................................................................................5.01 The Constitution .....................................................................................5.01 The Taif (Ta’if/Taef) Agreement...........................................................5.02 Citizenship and nationality ...................................................................5.03 Kurds ...............................................................................................5.05 -

Kent Academic Repository Full Text Document (Pdf)

Kent Academic Repository Full text document (pdf) Citation for published version Hassouneh, Nadine (2015) (Re)tuning Statelessness. Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) thesis, University of Kent. DOI Link to record in KAR https://kar.kent.ac.uk/55209/ Document Version UNSPECIFIED Copyright & reuse Content in the Kent Academic Repository is made available for research purposes. Unless otherwise stated all content is protected by copyright and in the absence of an open licence (eg Creative Commons), permissions for further reuse of content should be sought from the publisher, author or other copyright holder. Versions of research The version in the Kent Academic Repository may differ from the final published version. Users are advised to check http://kar.kent.ac.uk for the status of the paper. Users should always cite the published version of record. Enquiries For any further enquiries regarding the licence status of this document, please contact: [email protected] If you believe this document infringes copyright then please contact the KAR admin team with the take-down information provided at http://kar.kent.ac.uk/contact.html (Re)tuning*Statelessness** ! Academic(knowledge(production(on(Palestine(and(its(people(has(been(very(resonant(for( decades.(Yet,(and(despite(the(high(frequency(of(production,(some(aspects(of(Palestine( and( Palestinians( have( not( been(investigated(nor(brought(together(thus(far.((This( composition( fuses( three( reverberations( that( accompany( Palestinians( living( away( from( their(homeland:(statelessness,(diasporisation,(and((de)mobilisation.(The(dissertation(is( -

GAZA Situation Map - As of 5Th of January 2009

GAZA Situation Map - as of 5th of January 2009 Reported Palestinian casualties as of 5 January 2009 * Killed 534 20% of killed Palestinians Siafa are civilians Injured Erez crossing point is partially open 2,470 Al Qaraya al Badawiya for a limited number of medical al Maslakh evacuations and foreign nationals. Madinat al 'Aw da Beit Lahiya * Beit Hanoun Situation Jabalia Camp Ash Shati' Camp • More than a million Gazans still have 'Izbat Beit Hanoun no electricity or water, and thousands Gaza Jabalia = 25 people = 25 people of people have fled their homes for safe Wharf shelter. Based on MoH as of 5 January 2009 40% of injured Palestinians are civilians * 'A rab Maslakh Beit Lahiya • Hospitals are unable to provide adequate Reported Israeli casualties as of 5 January 2009 Gaza intensive care to the high number of Killed * casualties. 8 of which 4 are civilians crossing point for fuels - open today. dead and at least injured Injured Nahal Oz • 534 2470 of which 46 are civilians 215,000 litres of industrial fuel along with 47 tonnes since 27 December, Source: Palestinian 106 of cooking gas have been pumped from Israel to Gaza Ministry of Health MoH, as of 5th of = 25 people January 2009. = 25 people Al Zahra Al Mughraqa Karni crossing * Based on the Israeli Magen David Adom and the Israeli (Abu Middein) Defence Force (IDF), as of 5 January point for goods • 60 IDF soldiers have been wounded in Gaza since Saturday the 4th of Jan., Priority Needs: including four who remain in serious condition. • Industrial fuel is needed to power the Gaza Power Plant. -

Localities-1997-Class.Pdf

7991 7991 79 7991 7171 4141 41 4119 7991 7411 (972-2) 298 6343 (972-2) 298 6340 http://www. pcbs. org [email protected] http://www. palphc. org : 4 3 1 5 9 9 1 41 41 41 41 41 41 41 41 41 4119 4119 1 914 4119 51111 4 Centroid 1115 14 41 5 14 4 15 1 41 3 45 1 11 5 15 1 31 9 35 1 11 1 15 41 51 44 55 41 11 43 15 41 91 45 95 41 1 1 3 1 9 Loc. Governorate Locality Name Code JENIN Zububa 010005 JENIN Rummana 010010 JENIN Ti'innik 010015 JENIN At Tayba 010020 JENIN 'Arabbuna 010025 JENIN Al Jalama 010030 JENIN Silat al Harithiya 010035 As Sa'aida JENIN 010040 JENIN 'Anin 010045 JENIN 'Arrana 010050 JENIN Deir Ghazala 010055 JENIN Faqqu'a 010060 Khirbet Abu 'Anqar JENIN 010065 Khirbet Suruj JENIN 010070 Dahiyat Sabah al Kheir JENIN 010075 JENIN Al Yamun 010080 JENIN Umm ar Rihan 010085 JENIN 'Arab al Hamdun 010090 JENIN Kafr Dan 010095 JENIN Barghasha 010100 Khirbet 'Abdallah al Yunis JENIN 010105 JENIN Mashru' Beit Qad 010110 JENIN Dhaher al Malih 010115 JENIN Barta'a ash Sharqiya 010120 JENIN Al 'Araqa 010125 Khirbet ash Sheikh Sa'eed JENIN 010130 1 Loc. Governorate Locality Name Code JENIN Al Jameelat 010135 JENIN Beit Qad 010140 JENIN Tura al Gharbiya 010145 JENIN Tura ash Sharqiya 010150 JENIN Al Hashimiya 010155 JENIN Umm Qabub 010160 JENIN Nazlat ash Sheikh Zeid 010165 JENIN At Tarem 010170 Khirbet al Muntar al Gharbiya JENIN 010175 JENIN Jenin 010180 JENIN Jenin Camp 010185 JENIN Jalbun 010190 JENIN 'Aba 010195 Khirbet Mas'ud JENIN 010200 Khirbet al Muntar ash Sharqiya JENIN 010205 JENIN Kafr Qud 010210 JENIN Deir Abu Da'if 010215 JENIN Birqin 010220 JENIN Umm Dar 010225 JENIN Al Khuljan 010230 Wad ad Dabi' JENIN 010235 JENIN Dhaher al 'Abed 010240 JENIN Zabda 010245 Qeiqis JENIN 010255 JENIN Al Manshiya 010260 JENIN Ya'bad 010265 1 Loc. -

Life in Limbo

1 Executive Summary Introduction Historical context and definitions: refugees vs. IDPs vs. migrants On the media radar: ‘boat people’ Lebanon: Ground Zero for the Refugee Debate Palestinians of Lebanon: ‘The forgotten people’ A tale of two Lebanese youth and their ‘awakening’ Education Employment Two Palestinian women insist on the right to work Health care Filling in the gaps in social services Life in the camps From Nahr Al-Bared to Ayn Al-Hilweh: Camps and insurgency The Syrian Influx Syrian Palestinians: Displaced twice-over Two Syrian Palestinians: Fleeing from one hot spot to another Syrian refugees and the UNHCR Shelter From farming to chicken coops Education Are American companies attempting to turn aid into profit? Employment Syrian refugees: employed, but struggling Health care The Way Forward: Toward a More Humane Refugee Policy Recommendations Sonbola: Syrians empowering Syrians through education Plan from the ‘bottom up’ instead of ‘top down’ The special case of the Palestinians: Restore their human rights Recommendation 2 Executive Summary There is no debate about the magnitude of the refugee crisis the world now faces. In its 2014 global-trends report, “World at War,” the UN High Commissioner of Human Rights (UNHCR) warned that the last year has seen the highest number of forcibly displaced people since it began keeping records. “We are witnessing a paradigm change, an unchecked slide into an era in which the scale of global forced displacement as well as the response required is now clearly dwarfing anything seen before,” said Antonio Guterres, UN High Commissioner for Refugees. Most of the ensuing discussion has focused on the immediate crisis of the moment: how to stop smugglers, which countries should accept how many asylum seekers, how host countries can better cope with the influx, how much money is needed from donor countries. -

Palestinian Population by Health Insurance Coverage* 3,458,128 1,669,731 1,788,397

State of Palestine Palestinian Central Bureau of statistics (PCBS) Preliminary Results of the Population, Housing and Establishments Census, 2017 February , 2018 Preliminary Census Results, PHC 2017 1 All correspondence should be directed to: Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics P. O. Box 1647, Ramallah, Palestine Tel: (970) 2 298 2 700 Fax: (970) 2 2982 710 Email: [email protected] Web-site: http://www.pcbs.gov.ps Branch offices: Office in the Northern area- Nablus Telephone: 09-2381752 Fax: 09-2387230 Office in the Middle area- Ramallah Telephone: 02-2988717 Fax: 02-2956478 Office in the Southern area- Hebron Telephone: 02-2220222 Fax: 02-2252865 Gaza office: Telephone: 08-2641087 Fax: 08-2641090 Toll Free: 1800 300 300 /PCBSPalestine Cover photo by: Marthie Momberg (Children from Alwalaja, Palestine) Printing of this report was funded by the European Union 2 Preliminary Census Results, PHC 2017 Acknowledgement The Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics (PCBS) wishes to express its gratitude to all of the Palestinian people, who contributed to the success of the Population, Housing and Establishments Census, 2017. PCBS commends their full cooperation in delivering the data needed. PCBS would like also to thank its unknown soldiers – the staff – for their dedication and exceptional efforts in all phases of the Census. PCBS further expresses special thanks to the efforts of the president and members of the Central Operations Room, president and members of the Census Executive Committee, District Operations Rooms and Governorates’ Census Managers and their assistants, support staff, media coordinators, field supervisors, observers and enumerators. PCBS thanks all of the committees and teams of the Census. -

Report of the Commissioner-General of the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees

I I REPORT OF THE COMMISSIONER-GENERAL OF THE UNITED NATIONS RELIEF AND WORKS AGENCY FOR PALESTINE REFUGEES. IN THE---NEAR EAST 1 July 1976 - 30 June 1977 GENERAL ASSEMBLY OFFICIAL RECORDS: THIRTY-SECOND SESSION SUPPlEMENT No. 13 (A/32/13) UNITED NATIONS New York, 1977 I NOTE Symbols of United Nations documents are composed of capital letters combined with tlgures. Mention ofsuch a symbol indicates a reference to a United Nations document. • III LOriginal: Arabic/English/French/ /9 September 197'1/ COHT:J:NTS Paragr~Fhs Pa~e Chapter Letter of transmittal •••.•••••••••.•• vi Letter from the Chairman of the Advisory Commission of the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East .•••.. viii INTRODUCTIon 1 - 28 1 General ••• ... 1 - 5 1 6 2 Agency ~rogrammes •. '. ... Finmlcing the programmes .. .. 7 - 12 3 26 5 Special problel~ .. .. .. 13 - Conclusion 27 - 28 9 I. REPORT OF THE OPERATIONS OF THE AGE~Cy'FROM 1 JULY 1976 TO 30 JUNE 1977 . 29 - 170 11 A. General. ...•.•.. 29 - 37 11 Assistance from voluntary agencies and other non-governmental organizations ..••. 30 - 31 11 TIelations with other or~ans of the Dnited Nations system •••..• 32 - 37 11 B. Education and training services . .. 38 - 65 12 General education •.••••• 40 - 50 12 Vocational and technical education . ... 51 - 55 15 Teacher training .•.• ... 56 - 64 16 University scholarships • . 65 19 C. Relief services .••.• .. ... ... 66 - 98 19 Eligibility, registration and basic rations . 68 - 71 19 Camps and shelters 72 - 89 21 98 24 ~'ielfare . .. ... .. 90 - -iii- CONTDNTS (continued) ; .Chapter Para~raphs r~ D. Health services ·· · · · · · · · · · · 99 - 134 26 Control of cO~llunicable diseases 106 - 109 27 J:.iaterna1 and child health 110 - 115 28 ~ · · · · Nursine services 116 - 117 29 7i · · · 4 Environmental health · · · · 118 - 122 29 Nutrition including suppler..1entary feedil1C; · ·· · · 123 - 131 30 ii Ivledica1 .and paramedical education and traininE\ · · 132 - 134 32 l E. -

Governing Palestinian Refugee Camps in the Arab East

Policy and Governance in The Issam Fares Institute for Public Policy and International Aairs (IFI) Palestinian Refugee Camps American University of Beirut | PO Box 11-0236, Riad El Solh 1107 2020, Beirut, Lebanon | Tel: +961-1-374374, Ext: 4150 | Fax: +961-1-737627 | Email: [email protected] October 2010 Governing Palestinian Refugee Camps in the Arab East: Governmentalities in Search of Legitimacy Sari Hana Associate Professor, Department of Social and Behavioral Sciences Program Research Director, Issam Fares Institute for Public Policy and International Affairs, American University of Beirut Working Paper Series Paper Working #1 Issam Fares Institute for Public Policy and International Affairs American University of Beirut Policy and Governance in Palestinian Refugee Camps Working Paper Series #1 | October 2010 Governing Palestinian Refugee Camps in the Arab East: The Program on Policy and Governance in Palestinian Refugee Camps in the Governmentalities in Search of Middle East is run jointly by IFI and the Center for Behavioral Research at Legitimacy AUB. It brings together academic and policy-related research on Palestinian refugee camps from around the world. The program aims to be an open and non-partisan coordinating mechanism for researchers, civil society, government officials, and international organiza- tions, in order to generate accurate analysis and policy recommendations on Palestinian refugee camps throughout the Middle East. Sari Hanafi Associate Professor, Department of Social and Behavioral Sciences Rami G. Khouri IFI -

Annual Report 2004

Welfare Association Annual Report 2004 A continued commitment to sustainable development and humanitarian assistance in Palestine www.welfareassociation.org Mission Statement As a leading Palestinian non-governmental development organization, the Welfare Association is dedicated to making a distinguished contribution toward furthering the progress of the Palestinians, preserving their heritage and identity, supporting their living culture and building civil society. It aims to achieve these goals by methodically identifying Palestinian needs and priorities and establishing sound mechanisms in order to maximize benefits from the available funding resources. Geneva P.O.Box 6269 CH-1211Geneva 6 SWITZERLAND Jerusalem P.O.Box 25204 JERUSALEM Tel: (972-2) 234-3922/35 Fax: (972-2) 234-3936 E-mail:[email protected] Amman P.O.Box 840888 Amman 11184 JORDAN Tel: (962-6) 585-0600 Fax: (962-6) 585-5050 E-mail:[email protected] www.welfareassociation.org London Sister Organization: Welfare Association (UK) 5 Princes Gate, Kensington Road London SW7 1QJ U.K. Tel: (442-7) 589 8035 Fax: (442-7) 589 7392 E-mail: [email protected] 2 3 Board of Trustees (2002-2005) Abdul Majeed Shoman (Chairman Of The Board) Abdul Aziz Shakhashir (Vice-chairman) Abdul Muhsen Al-Qattan (Vice-chairman) Adel Afifi Ali Al-Radwan Basel Aql Faisal Abdulhadi Faisal Alami George Abed Hasib Sabbagh (Vice-chairman) Hisham Qaddoumi Issam Azmeh Jawdat Shawwa Khaled Sifri (Chairman, Management Committee) Mamdouh Aker Marwan Sayeh Munir Kaloti Munib Masri (Vice-chairman)