Confederate Memorialization and the Old South's Reckoning with Modernity in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

843.953.6956 Ellison Capers

The Citadel Archives & Museum 171 Moultrie Street Charleston, S.C. Telephone 843.953.6846 Fax: 843.953.6956 ELLISON CAPERS PAPERS A1961.1 BIOGRAPHY From the Dictionary of American Biography Base Set. American Council of Learned Societies, 1928-1936. Ellison Capers (Oct. 14, 1837-Apr. 22, 1908), Confederate soldier, Episcopal bishop, was born in Charleston, South Carolina. His parents were William Capers and Susan (McGill) Capers. With the exception of two years in Oxford, Georgia, Ellison Capers spent his childhood and youth in Charleston, where he attended the two private schools and the high school. He received additional training in the Conference School, Cokesbury, and in Anderson Academy. In 1854 he entered the South Carolina Military Academy (The Citadel). He graduated in 1857 and taught for that year at The Citadel as an instructor in mathematics. In 1858, he served as principal of the preparatory department at Mt. Zion College, Winnsboro, South Carolina but returned to The Citadel in January 1859 as assistant professor of mathematics. The next month he married Charlotte Palmer of Cherry Grove Plantation. At the outbreak of the Civil War, Capers was elected major of a volunteer regiment which took part in the bombardment of Fort Sumter. This organization gave way to a permanent unit, the 24th South Carolina Infantry, of which Capers was 1 lieutenant-colonel. After two years of fighting in the Carolinas, the bloodiest occurring at the battles on James Island, the regiment was ordered in May 1863 to go with General Joseph E. Johnston to the relief of Vicksburg, Mississippi. From this time until the surrender at Bentonville, North Carolina, Capers was in the midst of hard campaigning and intense fighting. -

Caroliniana Columns - Fall 2016 University Libraries--University of South Carolina

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons University South Caroliniana Society Newsletter - South Caroliniana Library Columns Fall 2016 Caroliniana Columns - Fall 2016 University Libraries--University of South Carolina Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/columns Part of the Library and Information Science Commons Recommended Citation University of South Carolina, "University of South Carolina Libraries - Caroliniana Columns, Issue 40, Fall 2016". http://scholarcommons.sc.edu/columns/40/ This Newsletter is brought to you by the South Caroliniana Library at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in University South Caroliniana Society Newsletter - Columns by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. University South Caroliniana Society newsletter Fall 2016 Cokie Roberts Season’s greetings from the South Caroliniana Library (Photograph courtesy of the University Creative Services) Summer Scholars Find Treasures in the South Caroliniana Library The South Caroliniana Library serves many constituents, sharing its unique collections with University students and faculty, local historians and genealogists, and a multitude of researchers from around the world both in person and via its online resources. Each summer the Library welcomes budding researchers to its Sumer Scholars program which includes visiting fellowships and professorships from several sources. This summer the researchers and their assistantships included: Jacob Clawson, Ph.D. candidate, Auburn University, Governor Thomas Gordon McLeod and First Lady Elizabeth Alford McLeod Research Fellow Kevin Collins, Professor of Language and Literature, Southwestern Oklahoma State University, William Gilmore Simms Visiting Research Professor Mandy L. Cooper, Ph.D. candidate, Duke University, Lewis P. Jones Research Fellow Lauren Haumesser, Ph.D. -

Charleston County South Carolina PHOTOGRAPHS WRITTEN

Snee l"a.rm Ncar 'liOW1t Pleasant HiiBS !l0. Se-87 Charleston County South Carolina \"~ /\ E; ~;: L ., ..... ~',.-. • i 0' . ['i.>l(>. Ii ,\ PHOTOGRAPHS WRITTEN HISTORIC AND DESCRIPTIVE DATA • District of South Carolina Historic American Buildings Survey Prepared at Washington Office for Southeast Unit HJ..Bf No .. S::;EF~ FARi,,; Ner<.r :,~ount Pleasant, Chp<rlestC!l County I South Ca.rolina Ouic or ercctlon: c. 1750 Present co'~dition: Excellent frDJ:O construction; rectanc),lo..r plan; marble mantel, Adam de- sign .. A,lditc.onal data, One-ti:r.e horne of Colone 1 Charles Pinckney. ,'!as in Pinckney fami ly for sevent:! years • Othe~ e~~stinG !,ccords: .~ •• Cr,.arleston l:useu.T.1 Prepared by Junior Architect James L .. Burnett, Jr .. , " Approved :' Ii \,}.. J 4/! -;c. " Addendum To: SNEE FARM HABS NO. SC-87 1240 Long Point Road • Charleston Coun~y South Carolina PHOTOGRAPHS AND WRITTEN HISTORICAL AND DESCRIPTIVE DATA • REDUCED COPIES OF IfEASURED DRAHINGS • Historic American Buildings Survey National Park Service Department of the Interior • Washington, D.C. 20013-7127 ~A6S 5(. , \O-(i\ouf)v HISTORIC AMERICAN BUILDINGS SURVEY j ~) - SNEE FARM • HABS NO. SC-87 Location: 1240 Long Point Road, Mt. Pleasant, Charleston County, South Carolina 4.6 miles NE of Mt. Pleasant on US Hwy 17; turn left on County Road 97 (Long Point Road); continue 0.7 mile and turn left on dirt road; house is 0.1 mile down dirt road on left. UTM: 17.609960.3634640 Present Owner: National Park Service Present Use: Vacant Significance: The Charles Pinckney Historic Site, known traditionally as "Snee Farm," is the ancestral country seat of Charles pinckney III, the American patriot and statesman. -

Section 1 General Information BRIGADIER GENERAL MICAH JENKINS CAMP 1569 SONS of CONFEDERATE VETERANS

Section 1 General Information BRIGADIER GENERAL MICAH JENKINS CAMP 1569 SONS OF CONFEDERATE VETERANS MEMBER HANDBOOK GENERAL INFORMATION Heritage of Honor The citizen-soldiers who fought for the Confederacy personified the best qualities of America. The preservation of liberty and freedom was the motivating factor in the South's decision to fight the Second American Revolution. The tenacity with which Confederate soldiers fought underscored their belief in the rights guaranteed by the Constitution. These attributes are the underpinning of our democratic society and represent the foundation on which this nation was built. Today, the Sons of Confederate Veterans is preserving the history and legacy of these heroes, so future generations can understand the motives that animated the Southern Cause. The SCV is the direct heir of the United Confederate Veterans, and the oldest hereditary organization for male descendants of Confederate soldiers. Organized at Richmond, Virginia in 1896, the SCV continues to serve as a historical, patriotic, and non-political organization dedicated to insuring that a true history of the 1861-1865 period is preserved. The SCV has ongoing programs at the local, state, and national levels which offer members a wide range of activities. Preservation work, marking Confederate soldiers' graves, historical re- enactments, scholarly publications, and regular meetings to discuss the military and political history of the War Between the States are only a few of the activities sponsored by local units, called camps. All state organizations, known as Divisions, hold annual conventions, and many publish regular newsletters to the membership dealing with statewide issues. Each Division has a corps of officers elected by the membership who coordinate the work of camps and the national organization. -

South Carolina ![Illiiiii:I;Iii:-Iiipi::F?^.Y: Richland County

Theme (5): Political and Military Affairs Form 10-300 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR STATE: (July 1969) NATIONAL PARK SERVICE South Carolina COUNTY; NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES Richland INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM FOR NPS USE ONLY ENTRY NUMBER (Type all entries — complete applicable sections) Millwood AND/OR HISTORIC: STREET AND NUMBER: Millwood, Garner's Ferry Road CITY OR TOWN: Co lumb ia South Carolina 4F Richland 40 uo CATEGORY ACCESSIBLE , L OWNERSHIP STATUS rc/iec/c One; TO THE PUBLIC Z Q District Q] Building l~l Public Public Acquisition: Occupied Yes: o 3 Restricted B Site Q Structure 6 Private || In Process Unoccupied D Unrestricted a object a Both I I Being Considered p reservatjon wofk in progress CD No PRESENT USE (Check One or More as Appropriate) Lj5f Agricultural Q Government D Park I I Transportation Comments [~"1 Commercial Q Industrial [^ Private Residence D Other (Specify) Q31 Educational Q Military Q Religious uo ( | Entertainment Q] Museum PI Scientific

Sleepy Times

DEPARTMENT OF ANESTHESIA AND PERIOPERATIVE MEDICINE SLEEPY TIMES VOLUME 11, ISSUE 8 AUGUST 2017 Message from the Chairman: Substantial Achievements -Scott T. Reeves, M.D., MBA Inside This Issue: For another year, MUSC Health has received significant accolades from U.S. News & World Report. We were nationally ranked in six -Message from Chairman 1 children’s specialties with a new high ranking of #11 for our -MUSC Ranks in US News 2 Cardiology and Heart Surgery program. In this edition of Sleepy & World Report Again Times, Eric Graham has highlighted our star ratings from the -Research Corner 3 Society of Thoracic Surgery as well. -Charleston Tops Travel 4 + Leisure Ranks Again Charleston again has been recognized as the #1 city in the United States in which -Department Events 5-8 to vacation and #2 in the world according to Travel + Leisure Magazine. -Malignant Hyperthermia 9-10 I am also excited about the growing leadership opportunities available to our faculty with Dr. Alan Finley assuming the very important position of Ashley -Grand Rounds 11 River Tower Medical Director. We are also adding statistical research support -I Hung the Moon 12 with the recruitment of Laney Wilson, PhD. As we start FY18, the department has a lot to be thankful for and the year is shaping up to be great. PAGE 2 SLEEPY TIMES MUSC Ranked in US News & World Report’s best children’s hospitals On behalf of the leadership team of MUSC Children’s Health, we would like to announce the results of this year’s U.S. News & World Report’s edition of America’s Best Children’s Hospitals. -

Historic Building Survey of Upper King, Upper Meeting Street and Intersecting Side Streets Charleston, South Carolina

______________________________________________________________________________ HISTORIC BUILDING SURVEY OF UPPER KING, UPPER MEETING STREET AND INTERSECTING SIDE STREETS CHARLESTON, SOUTH CAROLINA Figure 1. Bird’s Eye of Upper King and Meeting Streets Prepared by: HPCP 290 Maymester 2009 The College of Charleston Charleston, South Carolina 29401 MAY 2009 ______________________________________________________________________________ ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Six students at the College of Charleston Historic Preservation & Community Planning Program put the following historic building survey and report for Upper King and Meeting Streets as part of a class project in May 2009 for the City of Charleston Department of Planning, Preservation & Economic Innovation. The main points of contact were Debbi Hopkins, Senior Preservation Planner for the City of Charleston and Dr. Barry Stiefel, Visiting Assistant Professor for the College of Charleston and Clemson University. Dr. Stiefel served as the Project Manager for the historic building survey and was assisted by Meagan Baco, MSHP, from the joint College of Charleston-Clemson University Graduate Historic Preservation Program, who served as Graduate Student Instructor and Principle Investigator. Ms. Baco’s Master’s Thesis, One-way to Two-way Street Conversions as a Preservation and Downtown Revitalization Tool: The Case Study of Upper King Street, Charleston, South Carolina, focused on the revitalization of the Upper King Street area. However, this survey project and report would not have been possible -

MESSENGER on the COVER in the Spirit of Sankofa

WINTER 2018 MESSENGER ON THE COVER In the Spirit of Sankofa A Publication of the The cover features the adinkra Sankofa heart symbol. Underneath is, an image of the autographed sentiment, “In the Spirit of Sankofa,” by Dr. Marlene O’Bryant-Seabrook. AVERY RESEARCH CENTER FOR AFRICAN AMERICAN HISTORY AND CULTURE The autograph is from Georgette Mayo’s personal copy College of Charleston of A Communion of the Spirits: African-American Quilters, 125 Bull Street • Charleston, SC 29424 Preservers, and Their Stories by Roland Freeman (Rutledge Hill Ph: 843.953.7609 • Fax: 843.953.7607 Press 1996). Dr. O’Bryant-Seabrook is a featured quilt artist in Archives: 843.953.7608 the book. In the background is Dr. O’Bryant-Seabrook’s quilt, avery.cofc.edu Gone Clubbing: Crazy About Jazz (2008). Adinkra are visual symbols that AVERY INSTITUTE OF AFRO-AMERICAN HISTORY AND CULTURE represent proverbs relating to history PO Box 21492 • Charleston, SC 29413 and customs of the Asante people of Ph: 843.953.7609 • Fax: 843.953.7607 West Africa. Sankofa means “go back www.averyinstitute.us to the past in order to build for the future.” We should learn from the past STAFF and move forward into the future with Patricia Williams Lessane, Executive Director that knowledge. A stylized heart, as Barrye Brown, Reference and Outreach Archivist featured on the cover, or a bird with Daron L. Calhoun II, RSJI Coordinator its head turned back while walking Curtis J. Franks, Curator; Coordinator of Public forward, are the two symbols used Programs and Facilities Manager to represent Sankofa. -

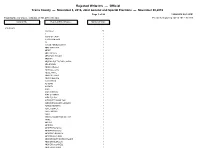

Rejected Write-Ins

Rejected Write-Ins — Official Travis County — November 8, 2016, Joint General and Special Elections — November 08,2016 Page 1 of 28 12/08/2016 02:12 PM Total Number of Voters : 496,044 of 761,470 = 65.14% Precincts Reporting 247 of 268 = 92.16% Contest Title Rejected Write-In Names Number of Votes PRESIDENT <no name> 58 A 2 A BAG OF CRAP 1 A GIANT METEOR 1 AA 1 AARON ABRIEL MORRIS 1 ABBY MANICCIA 1 ABDEF 1 ABE LINCOLN 3 ABRAHAM LINCOLN 3 ABSTAIN 3 ABSTAIN DUE TO BAD CANDIA 1 ADA BROWN 1 ADAM CAROLLA 2 ADAM LEE CATE 1 ADELE WHITE 1 ADOLPH HITLER 2 ADRIAN BELTRE 1 AJANI WHITE 1 AL GORE 1 AL SMITH 1 ALAN 1 ALAN CARSON 1 ALEX OLIVARES 1 ALEX PULIDO 1 ALEXANDER HAMILTON 1 ALEXANDRA BLAKE GILMOUR 1 ALFRED NEWMAN 1 ALICE COOPER 1 ALICE IWINSKI 1 ALIEN 1 AMERICA DESERVES BETTER 1 AMINE 1 AMY IVY 1 ANDREW 1 ANDREW BASAIGO 1 ANDREW BASIAGO 1 ANDREW D BASIAGO 1 ANDREW JACKSON 1 ANDREW MARTIN ERIK BROOKS 1 ANDREW MCMULLIN 1 ANDREW OCONNELL 1 ANDREW W HAMPF 1 Rejected Write-Ins — Official Travis County — November 8, 2016, Joint General and Special Elections — November 08,2016 Page 2 of 28 12/08/2016 02:12 PM Total Number of Voters : 496,044 of 761,470 = 65.14% Precincts Reporting 247 of 268 = 92.16% Contest Title Rejected Write-In Names Number of Votes PRESIDENT Continued.. ANN WU 1 ANNA 1 ANNEMARIE 1 ANONOMOUS 1 ANONYMAS 1 ANONYMOS 1 ANONYMOUS 1 ANTHONY AMATO 1 ANTONIO FIERROS 1 ANYONE ELSE 7 ARI SHAFFIR 1 ARNOLD WEISS 1 ASHLEY MCNEILL 2 ASIKILIZAYE 1 AUSTIN PETERSEN 1 AUSTIN PETERSON 1 AZIZI WESTMILLER 1 B SANDERS 2 BABA BOOEY 1 BARACK OBAMA 5 BARAK -

November 8, 2018 Charleston, SC a Meeting of Charleston County

November 8, 2018 Charleston, SC A meeting of Charleston County Council’s Finance Committee was held on November 8, 2018, in the Beverly T. Craven Council Chambers, Second Floor of the Lonnie Hamilton, III Public Services Building, located at 4045 Bridge View Drive, North Charleston, South Carolina. The following committee members were present: Herb Sass, Vice Chairman, who presided, Henry Darby, Anna Johnson, Brantley Moody, Teddie Pryor, Dickie Schweers, and J. Elliott Summey. Chairman Rawl and Mr. Qualey were absent. County Administrator Jennifer Miller and County Attorney Joe Dawson were also present. Mr. Pryor moved approval of the Finance Committee Minutes of October 18, 2018, seconded by Mr. Moody, and carried. The Vice Chairman stated the next item on the agenda was the Consent Agenda. Mr. Summey moved approval of the Consent Agenda, seconded by Mr. Pryor, and carried. Consent Agenda items are as follows: FY18 EMS ITEM A Grant in Aid County Administrator Jennifer Miller and Director of Emergency Medical Services Dave Program Abrams provided a report regarding applying and, if awarded, accepting grant funds for the FY18 EMS Grant in Aid Program. It was stated that the South Carolina Department Request to of Health and Environmental Control (DHEC), in accordance with Section 34.8 of the Approve part IB Provisos of the 2018–2019 Appropriations Act, will distribute state appropriated funds for the purpose of improving and upgrading the EMS system. Charleston County’s allocation for Fiscal Year 2018 – 2019, based upon the proportion of the population, is $26,136.30. EMS has the matching funds of 5.5% available. -

Coastal Heritage VOLUME 25, NUMBER 3 SPRING 2011

COASTAL HERITAGE VOLUME 25, NUMBER 3 SPRING 2011 Carolina Diarist The Broken World of Mary Chesnut SPRING 2011 • 1 3 CAROLINA DIARIST: THE BROKEN WORLD OF MARY CHESNUT Her compelling journal describes the four-year Science Serving South Carolina’s Coast Confederate rebellion, which aimed to preserve slavery but led to its extinction in North America. Coastal Heritage is a quarterly publication of the S.C. Sea Grant Consortium, a university- based network supporting research, education, 13 and outreach to conserve coastal resources and enhance economic opportunity for the people A RICH Man’s WAR, A POOR Man’s fight of South Carolina. Comments regarding this or future issues of Coastal Heritage are welcome at Why did poor Confederates fight? [email protected]. Subscriptions are free upon request by contacting: 14 S.C. Sea Grant Consortium 287 Meeting Street NEWS AND NOTES Charleston, S.C. 29401 • University of South Carolina student awarded Knauss fellowship phone: (843) 953-2078 • College of Charleston student secures research fellowship e-mail: [email protected] • Litter cleanup a success Executive Director • Blue crab populations decline in saltier water M. Richard DeVoe Director of Communications 16 Susan Ferris Hill Editor EBBS AND FLOWS John H. Tibbetts • 2011 National Aquaculture Extension Conference • Coastal Zone 2011 Art Director th Sara Dwyer • 4 National Conference on Ecosystem Restoration Sara Dwyer Design, LLC Board of Directors The Consortium’s Board of Directors is composed of the chief executive officers of its member institutions: Dr. Raymond S. Greenberg, Chair President, Medical University of South Carolina James F. Barker President, Clemson University Dr. -

Cavalry Raids | February 2020

Essential Civil War Curriculum | Scott Thompson, Cavalry Raids | February 2020 Cavalry Raids By Scott Thompson, West Virginia University merican warriors possessing a unique military and cultural reputation during and long after the Civil War were those cavalrymen who fought primarily through raids. More so than infantrymen, Civil War cavalrymen displayed the nineteenth- A 1 century values of glamor, adventure, endurance, chivalry, and courage. Contemporary observers and postbellum writers used colorful, romantic language to extol cavalrymen as uniquely skilled and brave warriors.2 Before the use of gasoline-powered vehicles in warfare, for centuries, the image of the warrior riding a strong, fast-moving animal struck fear into the unmounted enemy who became the target of a cavalry attack. Traditionally, the cavalry wing of a military force performed such duties as reconnaissance, scouting for the enemy’s location and strength, protecting its own flanks, and trying to outflank the enemy.3 Yet, due to their military effectiveness and cultural image, Civil War armies also sent their cavalry forces on separate, detached operations called raids. During these independent military actions, cavalry units rode behind enemy lines while relying on stealth. Raiders disrupted enemy supply lines, captured enemy commanders and forts, cut communication lines, destroyed railroads, caught enemy soldiers by surprise, battled gunboats, consumed enemy resources, and terrorized civilians. At times, raiders dismounted and fought as infantry. They fought with carbines, repeating rifles, and revolvers, weapons that could be fired more rapidly than the muskets of infantrymen. Cavalry raids blurred the boundary between conventional and irregular warfare. Due to their daring, destructive raids, the war’s Confederate cavalry commanders gave the Union Army some of its most acute headaches.