The Mechanics of Breathing and Speaking

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Phonation Types of Korean Fricatives and Affricates

ISSN 2005-8063 2017. 12. 31. 말소리와 음성과학 Vol.9 No.4 pp. 51-57 http://dx.doi.org/10.13064/KSSS.2017.9.4.051 Phonation types of Korean fricatives and affricates Goun Lee* Abstract The current study compared the acoustic features of the two phonation types for Korean fricatives (plain: /s/, fortis : /s’/) and the three types for affricates (aspirated : /tsʰ/, lenis : /ts/, and fortis : /ts’/) in order to determine the phonetic status of the plain fricative /s/. Considering the different manners of articulation between fricatives and affricates, we examined four acoustic parameters (rise time, intensity, fundamental frequency, and Cepstral Peak Prominence (CPP) values) of the 20 Korean native speakers’ productions. The results showed that unlike Korean affricates, F0 cannot distinguish two fricatives, and voice quality (CPP values) only distinguishes phonation types of Korean fricatives and affricates by grouping non-fortis sibilants together. Therefore, based on the similarity found in /tsʰ/ and /ts/ and the idiosyncratic pattern found in /s/, this research concludes that non-fortis fricative /s/ cannot be categorized as belonging to either phonation type. Keywords: Korean fricatives, Korean affricates, phonation type, acoustic characteristics, breathy voice 1. Introduction aspirated-like characteristic by remaining voiceless in intervocalic position. Whereas the lenis stops become voiced in intervocalic Korean has very well established three-way contrasts (e.g., position (e.g., /pata/ → / [pada] ‘sea’), the aspirated stops do not aspirated, lenis, and fortis) both in stops and affricates in three undergo intervocalic voicing (e.g., /patʰaŋ/ → [patʰaŋ] places of articulation (bilabial, alveolar, velar). However, this ‘foundation’). Since the plain fricative /s/, like the aspirated stops, distinction does not occur in fricatives, leaving only a two-way does not undergo intervocalic voicing, categorizing the plain contrast between fortis fricative /s’/ and non-fortis (hereafter, plain) fricative as aspirated is also possible. -

Phonological Use of the Larynx: a Tutorial Jacqueline Vaissière

Phonological use of the larynx: a tutorial Jacqueline Vaissière To cite this version: Jacqueline Vaissière. Phonological use of the larynx: a tutorial. Larynx 97, 1994, Marseille, France. pp.115-126. halshs-00703584 HAL Id: halshs-00703584 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-00703584 Submitted on 3 Jun 2012 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Vaissière, J., (1997), "Phonological use of the larynx: a tutorial", Larynx 97, Marseille, 115-126. PHONOLOGICAL USE OF THE LARYNX J. Vaissière UPRESA-CNRS 1027, Institut de Phonétique, Paris, France larynx used as a carrier of paralinguistic information . RÉSUMÉ THE PRIMARY FUNCTION OF THE LARYNX Cette communication concerne le rôle du IS PROTECTIVE larynx dans l'acte de communication. Toutes As stated by Sapir, 1923, les langues du monde utilisent des physiologically, "speech is an overlaid configurations caractéristiques du larynx, aux function, or to be more precise, a group of niveaux segmental, lexical, et supralexical. Nous présentons d'abord l'utilisation des différents types de phonation pour distinguer entre les consonnes et les voyelles dans les overlaid functions. It gets what service it can langues du monde, et également du larynx out of organs and functions, nervous and comme lieu d'articulation des glottales, et la muscular, that come into being and are production des éjectives et des implosives. -

Peak Flow Measure: an Index of Respiratory Function?

International Journal of Health Sciences and Research www.ijhsr.org ISSN: 2249-9571 Original Research Article Peak Flow Measure: An Index of Respiratory Function? D. Devadiga, Aiswarya Liz Varghese, J. Bhat, P. Baliga, J. Pahwa Department of Audiology and Speech Language Pathology, Kasturba Medical College (A Unit of Manipal University), Mangalore -575001 Corresponding Author: Aiswarya Liz Varghese Received: 06/12/2014 Revised: 26/12/2014 Accepted: 05/01/2015 ABSTRACT Aerodynamic analysis is interpreted as a reflection of the valving activity of the larynx. It involves measuring changes in air volume, flow and pressure which indicate respiratory function. These measures help in determining the important aspects of lung function. Peak expiratory flow rate is a widely used respiratory measure and is an effective measure of effort dependent airflow. Aim: The aim of the current study was to study the peak flow as an aerodynamic measure in healthy normal individuals Method: The study group was divided into two groups with n= 60(30 males and 30 females) in the age range of 18-22 years. The peak flow was measured using Aerophone II (Voice Function Analyser). The anthropometric measurements such as height, weight and Body Mass Index was calculated for all the participants. Results: The peak airflow was higher in females as compared to that of males. It was also observed that the peak air flow rate was correlating well with height and weight in males. Conclusions: Speech language pathologist should consider peak expiratory airflow, a short sharp exhalation rate as a part of routine aerodynamic evaluation which is easier as compared to the otherwise commonly used measure, the vital capacity. -

Part 1: Introduction to The

PREVIEW OF THE IPA HANDBOOK Handbook of the International Phonetic Association: A guide to the use of the International Phonetic Alphabet PARTI Introduction to the IPA 1. What is the International Phonetic Alphabet? The aim of the International Phonetic Association is to promote the scientific study of phonetics and the various practical applications of that science. For both these it is necessary to have a consistent way of representing the sounds of language in written form. From its foundation in 1886 the Association has been concerned to develop a system of notation which would be convenient to use, but comprehensive enough to cope with the wide variety of sounds found in the languages of the world; and to encourage the use of thjs notation as widely as possible among those concerned with language. The system is generally known as the International Phonetic Alphabet. Both the Association and its Alphabet are widely referred to by the abbreviation IPA, but here 'IPA' will be used only for the Alphabet. The IPA is based on the Roman alphabet, which has the advantage of being widely familiar, but also includes letters and additional symbols from a variety of other sources. These additions are necessary because the variety of sounds in languages is much greater than the number of letters in the Roman alphabet. The use of sequences of phonetic symbols to represent speech is known as transcription. The IPA can be used for many different purposes. For instance, it can be used as a way to show pronunciation in a dictionary, to record a language in linguistic fieldwork, to form the basis of a writing system for a language, or to annotate acoustic and other displays in the analysis of speech. -

The Acoustic Consequences of Phonation and Tone Interactions in Jalapa Mazatec

The acoustic consequences of phonation and tone interactions in Jalapa Mazatec Marc Garellek & Patricia Keating Phonetics Laboratory, Department of Linguistics, UCLA [email protected] San Felipe Jalapa de Dıaz⁄ (Jalapa) Mazatec is unusual in possessing a three-way phonation contrast and three-way level tone contrast independent of phonation. This study investigates the acoustics of how phonation and tone interact in this language, and how such interactions are maintained across variables like speaker sex, vowel timecourse, and presence of aspiration in the onset. Using a large number of words from the recordings of Mazatec made by Paul Kirk and Peter Ladefoged in the 1980s and 1990s, the results of our acoustic and statistical analysis support the claim that spectral measures like H1-H2 and mid- range spectral measures like H1-A2 best distinguish each phonation type, though other measures like Cepstral Peak Prominence are important as well. This is true regardless of tone and speaker sex. The phonation type contrasts are strongest in the first third of the vowel and then weaken towards the end. Although the tone categories remain distinct from one another in terms of F0 throughout the vowel, for laryngealized phonation the tone contrast in F0 is partially lost in the initial third. Consistent with phonological work on languages that cross-classify tone and phonation type (i.e. ‘laryngeally complex’ languages, Silverman 1997), this study shows that the complex orthogonal three-way phonation and tone contrasts do remain acoustically distinct according to the measures studied, despite partial neutralizations in any given measure. 1 Introduction Mazatec is an Otomanguean language of the Popolocan branch. -

Spirometry Basics

SPIROMETRY BASICS ROSEMARY STINSON MSN, CRNP THE CHILDREN’S HOSPITAL OF PHILADELPHIA DIVISION OF ALLERGY AND IMMUNOLOGY PORTABLE COMPUTERIZED SPIROMETRY WITH BUILT IN INCENTIVES WHAT IS SPIROMETRY? Use to obtain objective measures of lung function Physiological test that measures how an individual inhales or exhales volume of air Primary signal measured–volume or flow Essentially measures airflow into and out of the lungs Invaluable screening tool for respiratory health compared to BP screening CV health Gold standard for diagnosing and measuring airway obstruction. ATS, 2005 SPIROMETRY AND ASTHMA At initial assessment After treatment initiated and symptoms and PEF have stabilized During periods of progressive or prolonged asthma control At least every 1-2 years: more frequently depending on response to therapy WHY NECESSARY? o To evaluate symptoms, signs or abnormal laboratory tests o To measure the effect of disease on pulmonary function o To screen individuals at risk of having pulmonary disease o To assess pre-operative risk o To assess prognosis o To assess health status before beginning strenuous physical activity programs ATS, 2005 SPIROMETRY VERSUS PEAK FLOW Recommended over peak flow meter measurements in clinician’s office. Variability in predicted PEF reference values. Many different brands PEF meters. Peak Flow is NOT a diagnostic tool. Helpful for monitoring control. EPR 3, 2007 WHY MEASURE? o Some patients are “poor perceivers.” o Perception of obstruction variable and spirometry reveals obstruction more severe. o Family members “underestimate” severity of symptoms. o Objective assessment of degree of airflow obstruction. o Pulmonary function measures don’t always correlate with symptoms. o Comprehensive assessment of asthma. -

My Dissertation Will Be Composed of Roughly 7 Chapters

Copyright by Hansang Park 2002 Temporal and Spectral Characteristics of Korean Phonation Types by Hansang Park, B.A., M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin August, 2002 Dedication To my parents, Kapjo Park and Chanam Nam, and to my family, Yookyung Bae, Chanho Park, Dongho Park Acknowledgements I owe this work to so many people. This work would have been impossible without their help. First of all, I am so much indebted to Professor Robert T. Harms. He was my supervisor, professor, and graduate advisor, while I was studying in the Ph.D. program in Linguistics at the University of Texas at Austin. His comments on my work always kept me from deviating from the path I should be following. He encouraged me with wit and humor when I was frustrated. I was nourished to the fullest from discussions with him. I must confess that his broad, profound, and brewed knowledge about phonetics and linguistics is distilled into my work. When I was his teaching assistant, I was impressed at his professionalism in two ways. He was creative in preparing teaching materials and most kind to students during his classes. He taught me how to avoid mechanical grading and how to cherish students’ potentials and insights. He has two things I would like to inherit from him: the artificial larynx buzzer which is very useful to demonstrate the role of the source and filter in speech production and a peace of pipe organ which is helpful to teach the acoustic characteristics of the tube. -

NIOSH), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)

Technical Report Filtering Facepiece Respirators with an Exhalation Valve: Measurements of Filtration Efficiency to Evaluate Their Potential for Source Control Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health Technical Report Filtering Facepiece Respirators with an Exhalation Valve: Measurements of Filtration Efficiency to Evaluate Their Potential for Source Control DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health National Personal Protective Technology Laboratory This document is in the public domain and may be freely copied or reprinted. Disclaimer Mention of any company or product does not constitute endorsement by the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). In addition, citations to websites external to NIOSH do not constitute NIOSH endorsement of the sponsoring organizations or their programs or products. Furthermore, NIOSH is not responsible for the content of these websites. All web addresses referenced in this document were accessible as of the publication date. Get More Information Find NIOSH products and get answers to workplace safety and health questions: 1-800-CDC-INFO (1-800-232-4636) | TTY: 1-888-232-6348 CDC/NIOSH INFO: cdc.gov/info | cdc.gov/niosh Monthly NIOSH eNews: cdc.gov/niosh/eNews Suggested Citation NIOSH [2020]. Filtering facepiece respirators with an exhalation valve: measurements of filtration efficiency to evaluate their potential for source control. By Portnoff L, Schall J, Brannen J, Suhon N, Strickland K, Meyers J. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, DHHS (NIOSH) Publication No. -

Physical and Geometric Constraints Shape the Labyrinth-Like Nasal Cavity

Physical and geometric constraints shape the labyrinth-like nasal cavity David Zwickera,b,1, Rodolfo Ostilla-Monico´ a,b, Daniel E. Liebermanc, and Michael P. Brennera,b aJohn A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA 02138; bKavli Institute for Bionano Science and Technology, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA 02138; and cDepartment of Human Evolutionary Biology, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA 02138 Edited by Leslie Greengard, New York University, New York, NY, and approved January 26, 2018 (received for review August 29, 2017) The nasal cavity is a vital component of the respiratory system take into account geometric constraints imposed by the shape that heats and humidifies inhaled air in all vertebrates. Despite of the head that determine the length of the nasal cavity, its this common function, the shapes of nasal cavities vary widely cross-sectional area, and, generally, the shape of the space that it across animals. To understand this variability, we here connect occupies. To tackle this complex problem, we first show that, nasal geometry to its function by theoretically studying the air- without geometric constraints, optimal shapes have slender flow and the associated scalar exchange that describes heating cross-sections. We then demonstrate that these shapes can be and humidification. We find that optimal geometries, which have compacted into the typical labyrinth-like shapes without much minimal resistance for a given exchange efficiency, have a con- loss in performance. stant gap width between their side walls, while their overall shape can adhere to the geometric constraints imposed by the Results head. Our theory explains the geometric variations of natural The Flow in the Nasal Cavity Is Laminar. -

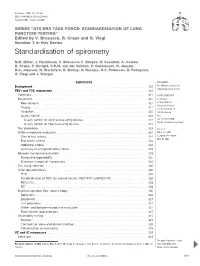

Standardisation of Spirometry

Eur Respir J 2005; 26: 319–338 DOI: 10.1183/09031936.05.00034805 CopyrightßERS Journals Ltd 2005 SERIES ‘‘ATS/ERS TASK FORCE: STANDARDISATION OF LUNG FUNCTION TESTING’’ Edited by V. Brusasco, R. Crapo and G. Viegi Number 2 in this Series Standardisation of spirometry M.R. Miller, J. Hankinson, V. Brusasco, F. Burgos, R. Casaburi, A. Coates, R. Crapo, P. Enright, C.P.M. van der Grinten, P. Gustafsson, R. Jensen, D.C. Johnson, N. MacIntyre, R. McKay, D. Navajas, O.F. Pedersen, R. Pellegrino, G. Viegi and J. Wanger CONTENTS AFFILIATIONS Background ............................................................... 320 For affiliations, please see Acknowledgements section FEV1 and FVC manoeuvre .................................................... 321 Definitions . 321 CORRESPONDENCE Equipment . 321 V. Brusasco Requirements . 321 Internal Medicine University of Genoa Display . 321 V.le Benedetto XV, 6 Validation . 322 I-16132 Genova Quality control . 322 Italy Quality control for volume-measuring devices . 322 Fax: 39 103537690 E-mail: [email protected] Quality control for flow-measuring devices . 323 Test procedure . 323 Received: Within-manoeuvre evaluation . 324 March 23 2005 Start of test criteria. 324 Accepted after revision: April 05 2005 End of test criteria . 324 Additional criteria . 324 Summary of acceptable blow criteria . 325 Between-manoeuvre evaluation . 325 Manoeuvre repeatability . 325 Maximum number of manoeuvres . 326 Test result selection . 326 Other derived indices . 326 FEVt .................................................................. 326 Standardisation of FEV1 for expired volume, FEV1/FVC and FEV1/VC.................... 326 FEF25–75% .............................................................. 326 PEF.................................................................. 326 Maximal expiratory flow–volume loops . 326 Definitions. 326 Equipment . 327 Test procedure . 327 Within- and between-manoeuvre evaluation . 327 Flow–volume loop examples. 327 Reversibility testing . 327 Method . -

Influence of Inhalation/Exhalation Ratio and of Respiratory

sustainability Article Slow-Paced Breathing: Influence of Inhalation/Exhalation Ratio and of Respiratory Pauses on Cardiac Vagal Activity Sylvain Laborde 1,2,* , Maša Iskra 1, Nina Zammit 1, Uirassu Borges 1,3, Min You 4, Caroline Sevoz-Couche 5 and Fabrice Dosseville 6,7 1 Department of Performance Psychology, Institute of Psychology, German Sport University Cologne, Cologne 50933, Germany; [email protected] (M.I.); [email protected] (N.Z.) 2 UFR STAPS, EA 4260 CESAMS, Normandie Université, 14000 Caen, France 3 Department of Health & Social Psychology, Institute of Psychology, German Sport University Cologne, 50933 Cologne, Germany; [email protected] 4 UFR Psychologie, EA3918 CERREV, Normandie Université, 14000 Caen, France; [email protected] 5 INSERM, Unité Mixte de Recherche (UMR) S1158 Neurophysiologie Respiratoire Expérimentale et Clinique, Sorbonne Université, 75000 Paris, France; [email protected] 6 UMR-S 1075 COMETE, Normandie Université, 14000 Caen, France 7 INSERM, UMR-S 1075 COMETE, 14000 Caen, France; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +49-221-49-82-57-01 Abstract: Slow-paced breathing has been shown to enhance the self-regulation abilities of athletes via its influence on cardiac vagal activity. However, the role of certain respiratory parameters (i.e., inhalation/exhalation ratio and presence of a respiratory pause between respiratory phases) still needs to be clarified. The aim of this experiment was to investigate the influence of these respiratory Citation: Laborde, S.; Iskra, M.; parameters on the effects of slow-paced breathing on cardiac vagal activity. A total of 64 athletes Zammit, N.; Borges, U.; You, M.; (27 female; Mage = 22, age range = 18–30 years old) participated in a within-subject experimental Sevoz-Couche, C.; Dosseville, F. -

Effects of Consonant Manner and Vowel Height on Intraoral Pressure and Articulatory Contact at Voicing Offset and Onset for Voiceless Obstruentsa)

Effects of consonant manner and vowel height on intraoral pressure and articulatory contact at voicing offset and onset for voiceless obstruentsa) Laura L. Koenigb) Haskins Laboratories, 300 George Street, New Haven, Connecticut 06511 and Long Island University, One University Plaza, Brooklyn, New York 11201 Susanne Fuchs Center for General Linguistics (ZAS), Schuetzenstrasse 18, Berlin 10117, Germany Jorge C. Lucero Department of Mathematics, University of Brasilia, Brasilia DF 70910-900, Brazil (Received 13 September 2010; revised 3 February 2011; accepted 12 February 2011) In obstruent consonants, a major constriction in the upper vocal tract yields an increase in intraoral pressure (Pio). Phonation requires that subglottal pressure (Psub) exceed Pio by a threshold value, so as the transglottal pressure reaches the threshold, phonation will cease. This work investigates how Pio levels at phonation offset and onset vary before and after different German voiceless obstruents (stop, fricative, affricates, clusters), and with following high vs low vowels. Articulatory contacts, measured using electropalatography, were recorded simultaneously with Pio to clarify how supra- glottal constrictions affect Pio. Effects of consonant type on phonation thresholds could be explained mainly in terms of the magnitude and timing of vocal-fold abduction. Phonation offset occurred at lower values of Pio before fricative-initial sequences than stop-initial sequences, and onset occurred at higher levels of Pio following the unaspirated stops of clusters compared to frica- tives, affricates, and aspirated stops. The vowel effects were somewhat surprising: High vowels had an inhibitory effect at voicing offset (phonation ceasing at lower values of Pio) in short-duration consonant sequences, but a facilitating effect on phonation onset that was consistent across conso- nantal contexts.