Ug: Boy Genius of the Stone Age by Raymond Briggs (Red Fox)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

KS3 Reading List

BURFORD SCHOOL ENGLISH DEPARTMENT KS3 reading suggestions While in Years 7, 8 and 9, you should try to read a wide variety of types of books. Don’t just stick to one author, or one genre. Experiment with something new. That is one reason why this list is arranged in genre-based sections. As well as reading books, don’t forget that newspapers and good magazines are also excellent reading material and will get you used to a range of reading experiences that will set you up well for GCSE and beyond, as well as broadening your knowledge and understanding of the world in which you live. The following websites are recommended and feature news and views about all types of books written for young people. So, as well as using this reading list, why not check the websites out too and see what other people are recommending? They will also give information about brand new books. http://www.readingmatters.co.uk/ http://www.booktrustchildrensbooks.org.uk/Teenage-Books http://www.cool-reads.co.uk/ http://www.lovereading4kids.co.uk/ http://www.ukchildrensbooks.co.uk/ RECOMMENDED READING Non-fiction Bill Bryson, Notes from a Big Country (and other travel books) - An American’s very funny perspective on Britain and British culture. Terry Deary, Horrible Histories – The gory aspects of history. Gerald Durrell, My Family and Other Animals - A young boy, fascinated by wildlife, and his crazy, funny family move to Crete. Anne Frank, The Diary of a Young Girl – Anne, a Jewish Dutch girl, has to hide from the Germans in a tiny secret room with her family and another family for two years. -

Rotten Romans Ebook, Epub

ROTTEN ROMANS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Terry Deary,Martin Brown | 240 pages | 04 Jun 2013 | Scholastic | 9781407135779 | English | London, United Kingdom Rotten Romans PDF Book Arghus Craig Roberts It was released on 26 July The strange facts within tell of everything from Rome's eccentric emperors and brutal armies; to its bizarre eating habits and gruesome taste in entertainment. Language: English. A depth of lessons almost contained within each chapter of the book. A good, fun and enthusiastic way to teach children about the Romans. Jul 29, Rachel rated it it was amazing Shelves: youngadult , history. Details if other :. But then this book could be treated as a sort of introduction, inspiring the reader to read f History without the boring bits to get kids interested in learning about past civilisations. Book Tickets Atti Croft is a Roman teenager with brains but very little brawn. The humour, information and games in the book offers depth to history as a subject which no other book can do, in my opinion. Goodreads helps you keep track of books you want to read. Somewhat predictably, the two youngsters from opposite sides of the conflict reach a mutual respect and understanding. Rotten Tomatoes. Please try again. I re-read this as I'm taking an A-level in archaeology and I am studying the Romans, obviously I will read lots of other books on the Romans aimed at adults, but I thought this was a nice place to start. When will my order arrive? I think this book is one of the only books that told me that the greatest and the most stupid things people did. -

Teacher's Overview

Teacher’s overview About this resource: The Snowman™ and The Snowdog film is the hugely successful sequel to Raymond Brigg’s Christmas classic The Snowman™ and was aired on television for the first time last year. It will provide some wonderfully festive inspiration to your English, Art, DT and PSHE lessons this autumn term. The resources created for Universal Pictures (UK) also include a series of crafting tutorials and videos to encourage children to engage in creative proJects to benefit members of our community who might need some extra care and attention this Christmas. This is an excellent opportunity for schools to reach out to the elderly and infirm through the provision of handmade gifts from the children. Why not organise a visit to a local nursing home for your class to present their gifts or invite them to your school assembly for a presentation? How to use this resource: These cross-curricular resources have been devised by educational consultants to meet the needs of teachers in Years 3 and 4. However, many of them can be adapted to meet Key Stage One objectives. SubJects include English, Art, DT and PSHE. For every lesson detailed below, there is a PowerPoint classroom presentation for use on white boards, and associated resources where relevant. There are teacher notes to be used in conjunction with the presentations, which will provide further context. You will also see a series of craft tutorials, which is listed at the end. Contents English with cross-curricular references to Art and Design • Lesson one: English National -

Media Guide 2015

MORRISONS GREAT NORTH RUN 2015 CELEBRITY LIST (correct 9 September 2015) Prof Brian Physicist and presenter of science James Olympic gold medallist and Cox television programmes, running for CracKnelL adventurer 654 the Jon Egging Trust 350 Steph BBC Breakfast business presenter PhiLippa Good Morning Britain presenter McGovern Breakthrough Breast Cancer Tomson 973 450 John BBC Weather presenter Jennifer BBC North East presenter Hammond Bartram 500 550 Elizabeth BBC London presenter AisLing BBC Weather Centre forecaster Rizzini Creevey 600 700 Geoff CooK Former English cricketer Kathryn Actress, Team Whiteley’s 2007 Apanowicz Wanderers, running for Marie Curie 567 Cancer Care Christa Former BBC Look North presenter, Jason VaLe The Juice Master AcKroyd Team Whiteley’s Wanderers, 2001 789 running for Marie Curie Cancer Care Kevin Former Everton, Sunderland and MichaeL Former Sunderland, Blackburn and KiLbane Ireland footballer Gray England footballer 800 333 Craig Former Middlesbrough footballer RendaLL Former European & Commonwealth Hignett Munroe Super Bantamweight boxer (the 950 850 'Boxing Binman', running for the Bodie Hodges Foundation Kenny ToaL ITV news presenter Ross ITV weather presenter 22222 Hutchinson 33333 Steve From Steve & Karen’s Breakfast Terry Deary Author ‘Horrible Histories’, running FurneLL Show on Metro Radio 888 for Grace House Children’s Hospice 1500 Tony Wish, Wire and Tower FM Tony Bob Hope in Emmerdale running for Horne presenter Audenshaw Bloodwise 2222 3500 George Ethan Hardy in Casualty running for CaL Mr Thackeray -

First Editions: Redrawn

FIRST EDITIONS: REDRAWN LONDON 8 DECEMBER 2014 FRONT COVER HOUSE OF ILLUSTRATION LOGO ILLUSTRATION © JEFF FISHER THIS PAGE LOT 15 THIS PAGE LOT 22 FIRST EDITIONS: REDRAWN AUCTION IN LONDON 8 DECEMBER 2014 SALE L14910 7.30 PM !DOORS OPEN AT 7.15 PM" EXHIBITION Friday 5 December 9 am-4.30 pm Sunday 7 December 12 noon-5 pm Monday 8 December 9 am-4.30 pm 34-35 New Bond Street London, W1A 2AA +44 (0)20 7293 5000 sothebys.com THIS PAGE LOT 16 SPECIALISTS AND AUCTION ENQUIRIES For further information on lots in this auction please contact any of the specialists listed below. SALE NUMBER SALE ADMINISTRATOR There is no buyer’s commission L14910 “ILLUSTRATION” Lukas Baumann charged for this sale. [email protected] BIDS DEPARTMENT +44 (0)20 7293 5287 Please note that all payment for +44 (0)20 7293 5283 !"# +44 (0)20 7293 5904 this sale must be made directly !"# +44 (0)20 7293 6255 with House of Illustration. [email protected] CATALOGUE PRICE £25 at the gallery Payment can be made on the Telephone bid requests should evening of sale or within 28 days Dr. Philip W. Errington be received 24 hours prior FOR SUBSCRIPTIONS CALL of the sale by contacting Director to the sale. This service is +44 (0)20 7293 5000 +44 (0)20 7293 5302 o$ ered for lots with a low estimate for UK & Europe Lucy Plaskett [email protected] of £2,000 and above. +1 212 606 7000 USA Head of Development and Communications PRIVATE CLIENT GROUP House of Illustration +44 %0&20 7293 6429 2 Granary Square [email protected] King’s Cross HEAD OF DEPARTMENT -

Rebecca's Story

Spring 2018 Chestnuts The newsletter from Chestnut Tree House Rebecca’s story ebecca Torricelli is 18 years old and has spinal muscular atrophy (SMA), a condition of the muscles and nervous system that affects around one in 8,000 people. She has never walked or crawled and Rhas always been in a wheelchair. Her condition affects her mobility, swallowing and respiratory system. Rebecca’s lungs are so susceptible to infection that a simple cold can lead to pneumonia and hospitalisation and her ability to swallow has deteriorated so much that she can now only eat puréed food. But despite all this, Rebecca, who is an extraordinary young lady, considers herself lucky: children with the most severe form of her condition rarely survive past infancy. She has kindly shared her story with us. “I can’t put into words what an amazing place it is and can only imagine what a haven it must have been for my parents.” I have been going to Chestnut Tree House since I was five years old. I was one of the first children to ever attend the hospice just after it was set up. Beforehand there was nowhere for struggling families to turn, and I can’t put into words what an amazing place it is and can only imagine what a haven it must have been for my parents. I was diagnosed with SMA type 1 when I was 15 months old, and my parents were originally told that I would lose all movement and muscle strength, so that I couldn’t even move my arms or head; I would not live past two years old. -

Horrible Histories

Horrible Histories In our opinion, the Horrible Histories television programmes contain some of the best comic writing out there and Terry Deary’s original books are masterful. They injected bounce into many a lesson, regardless of the class’ age. They also raise questions on the relationship between comedy and historical tragedy. For an energetic and playful start, pair up pupils and ask them to debate which of two historical periods was more ‘horrible’. If you have the books to hold up as you call out, even better! e.g. Vicious Vikings or Stormin’ Normans? or Angry Aztecs or Terrible Tudors? Using some volunteers, perform the stimulus as a piece of Readers’ Theatre (script in hand). Once read, recap on what each character is saying, and let them discuss the different views in small groups: Janey - We wouldn’t want people joking about today’s tragedies, so it’s not fair to joke about the past, Chris – Maybe some things can be joked about, others not Andy – if enough time passes, anything can become fair game, Morgan – Books like Horrible Histories are there to entertain, and we should leave it at that. To let pupils show their initial thinking on each perspective, summarise the views on a pieces of A3 paper and place one in the middle of the room. Tell pupils that to agree with it, they stand closer, and to disagree, they stand further away. You can briefly hear reasons, but try to move to the next one fairly swiftly, and so on. Do they have any other thoughts on this issue? I’ve deliberately excluded mention of black comedy and gallows humour, in the hope pupils will raise these concepts themselves. -

Little Childrens Nature Activity Book Pdf, Epub, Ebook

LITTLE CHILDRENS NATURE ACTIVITY BOOK PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Rebecca Gilpin | 68 pages | 31 May 2018 | Usborne Publishing Ltd | 9781474921695 | English | London, United Kingdom Little Childrens Nature Activity Book PDF Book Close Share options. Orion Children. The Velveteen Rabbit A sweet story that encourages kids to be caring. The visual imagery in her poetry is brilliantly captured in the accompanying quilts. Author and poet Jane Yolen and her son, Jason Stemple, a professional photographer, collaborated on this poetry book about egrets. This vividly illustrated book welcomes children to a world full of miracles. Because of the visual aspects of concrete poetry, it tends to be popular with kids. Written by J. If you've watched and read the story, you can almost see Raymond Briggs' illustrations dancing across the page. Hilda and the Troll is the first in the series, but there are many more, and the stories were recently made into a Netflix series, which is equally as good. Klassen's colour and illustration style juxtapose the traditionally vibrant world we usually see in picture books. Lawrence Sierra Club Books , , was written for older children but offers a thorough account of a wolf's life that is He escapes several times before he learns his lesson. Once kids pick it up, there's plenty to look at and it's a joy to follow along. The Snowman A touching tale of boy meets snowman. Some emphasize seasonal changes, like the changing colors of autumn leaves; others focus on common fall activities. If you have changed your email address then contact us and we will update your details. -

Ebook Download Horrible Geography of the World Ebook, Epub

HORRIBLE GEOGRAPHY OF THE WORLD PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Anita Ganeri, Mike Phillips | 96 pages | 02 Aug 2010 | Scholastic | 9781407117348 | English | London, United Kingdom Horrible Geography 12 Books Children Collection Set By Anita Ganeri – Bangzo Books Wholesale The Horrible Science of Everything. Planet in Peril! Horrible Geography. Currently unavailable. To get the free app, enter mobile phone number. See all free Kindle reading apps. Tell the Publisher! I'd like to read this book on Kindle Don't have a Kindle? Customer reviews. How are ratings calculated? Instead, our system considers things like how recent a review is and if the reviewer bought the item on Amazon. It also analyses reviews to verify trustworthiness. Review this product Share your thoughts with other customers. Write a product review. Top reviews Most recent Top reviews. Top review from India. There was a problem filtering reviews right now. Please try again later. Verified Purchase. It's an excellent way to introduce geography to children. One person found this helpful. See all reviews. Top reviews from other countries. I bought a 2nd hand copy, which arrived in a good condition. Fascinating book yep, I read this as a 26yr old adult :P I'm sure kids would love it too. Report abuse. Classic Horrible book - loved as usual by the 9 year old and educates us adults to. Based on the series of the books of the same name, this is a lively publication, written in various fonts with 'Wicked World Facts', 'Earth-shattering Facts', 'Teacher Teasers', cartoons, 'Horrible Health Warnings' Written with typical Horrible Geography humour, e. -

Gifts for Book Lovers HAPPY NEW YEAR to ALL OUR LOVELY

By Appointment To H.R.H. The Duke Of Edinburgh Booksellers Est. 1978 www.bibliophilebooks.com ISSN 1478-064X CATALOGUE NO. 338 JAN 2016 78920 ART GLASS OF LOUIS COMFORT TIFFANY Inside this issue... ○○○○○○○○○○ by Paul Doros ○○○○○○○○○○ WAR AND MILITARIA The Favrile ‘Aquamarine’ vase of • Cosy & Warm Knits page 10 1914 and the ‘Dragonfly’ table lamp are some of the tallest and most War is not an adventure. It is a disease. It is astonishingly beautiful examples of • Pet Owner’s Manuals page 15 like typhus. ‘Aquamarine’ glass ever produced. - Antoine de Saint-Exupery The sinuous seaweed, the • numerous trapped air bubbles, the Fascinating Lives page 16 varying depths and poses of the fish heighten the underwater effect. See pages 154 to 55 of this • Science & Invention page 13 78981 AIR ARSENAL NORTH glamorous heavyweight tome, which makes full use of AMERICA: Aircraft for the black backgrounds to highlight the luminescent effects of 79025 THE HOLY BIBLE WITH Allies 1938-1945 this exceptional glassware. It is a definitive account of ILLUSTRATIONS FROM THE VATICAN Gifts For Book by Phil Butler with Dan Louis Comfort Tiffany’s highly collectable art glass, Hagedorn which he considered his signature artistic achievement, LIBRARY $599.99 NOW £150 Lovers Britain ran short of munitions in produced between the 1890s and 1920s. Called Favrile See more spectacular images on back page World War II and lacked the dollar glass, every piece was blown and decorated by hand. see page 11 funds to buy American and The book presents the full range of styles and shapes Canadian aircraft outright, so from the exquisite delicacy of the Flowerforms to the President Roosevelt came up with dramatically dripping golden flow of the Lava vases, the idea of Lend-Lease to assist the from the dazzling iridescence of the Cypriote vases to JANUARY CLEARANCE SALE - First Come, First Served Pg 18 Allies. -

Issue 12 December.Pmd

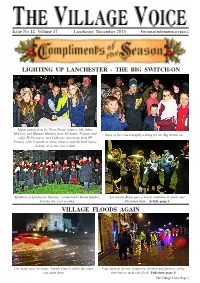

Issue No 12 Volume 17 Lanchester, December 2016 For contact information, see page 2 LIGHTING UP LANCHESTER - THE BIG SWITCH-ON Lights switched on by: Terry Deary (centre), left, Adam McCrory and Hannah Madeley from All Saints’ Primary and Some of the crowd happily waiting for the Big Switch-on. right, Eli Densmore and Catherine Armstrong from EP Primary with Councillors Ossie Johnson and Richard Young looking on at the rear (right). Members of Lanchester Operatic, conducted by David Hughes, Lanchester Brass gave a lovely rendition of carols and braving the cool evening, Christmas music. Article, page 5 VILLAGE FLOODS AGAIN Car going past All Saints’ Parish Church where the water Paul Jackson (front), volunteers, firemen and farmers, doing was quite deep. their best to tackle the flood. Full story, page 4 The Village Voice Page 1 THE Dear VILLAGE IT'S ALL Village.... VOICE ABOUT PEOPLE The views expressed in letters to the editor are not necessarily NEWS HOUNDS those of the newspaper, the editor or persons working for the Dear Village Voice Dear Village Voice newspaper. The editor retains the right to cut or amend any Burnhope Remembrance After the recent death NEEDED letter published. Letters must contain your name, address and Service, 13th November telephone no, all of which may be withheld at your request. of my wife, Pam Tilley, I The Village Voice is going 2016 would like to thank through a transitional Dear Village Voice roadway carries the It was a change to have a everyone for their stage. A new generation I have lived in Lanchester water from the west into nice dry day for the support, well wishes and of volunteers is needed to with my family since 1971. -

Comics and Graphic Novels for Young People

27 SPRING 2010 Going Graphic: Comics and Graphic Novels for Young People CONTENTS Editorial 2 ‘Remember Me’: An Afrocentric Reading of CONFERENCE ARTICLES Pitch Black 14 Kimberley Black The State of the (Sequential) Art?: Signs of Changing Perceptions of Comics, Manga and Graphic Novels and the Holocaust 15 Graphic Novels in Britain 3 Rebecca R. Butler Mel Gibson Copulating, Coming Out and Comics: The High From Tintin to Titeuf: Is the Anglophone Market School Comic Chronicles of Ariel Schragg 16 too Tough for French Comics for Children? 4 Erica Gillingham Paul Gravett Is Henty’s History Lost in Graphic Translation? The Short but Continuing Life of The DFC 5 Won by the Sword in 45 pages 17 David Fickling Rachel Johnson Out of the Box 6 Sequences of Frames by Young Creators: The Marcia Williams Impact of Comics in Children’s Artistic Development 18 Raymond Briggs: Blurring the Boundaries Vasiliki Labitsi among Comics, Graphic Novels, Picture Books and Illustrated Books 7 ‘To Entertain and Educate Young Minds’: Janet Evans Graphic Novels for Children in Indian Publishing 19 Graphic Novels in the High-School Malini Roy Classroom 8 Bill Boerman-Cornell Strangely Familiar: Shaun Tan’s The Arrival and the Universalised Immigrant Experience 20 Britain’s Comics Explosion 9 Lara Saguisag Sarah McIntyre Journeys in Time in Graphic Novels from Reading between the Lines: The Subversion of Greece 21 Authority in Comics and Graphic Novels Mariana Spanaki Written for Young Adults 10 Ariel Kahn Crossing Boundaries 22 Emma Vieceli Richard Felton Outcault and The Yellow Kid 10 Dora Oronti Superhero Comics and Graphic Novels 22 Jessica Yates As Old as Clay 11 Daniel Moreira de Sousa Pinna Composing and Performing Masculinities: Of Reading Boys’ Comics c.