Views About the Signing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Negro Press and the Image of Success: 1920-19391 Ronald G

the negro press and the image of success: 1920-19391 ronald g. waiters For all the talk of a "New Negro," that period between the first two world wars of this century produced many different Negroes, just some of them "new." Neither in life nor in art was there a single figure in whose image the whole race stood or fell; only in the minds of most Whites could all Blacks be lumped together. Chasms separated W. E. B. DuBois, icy, intellectual and increasingly radical, from Jesse Binga, prosperous banker, philanthropist and Roman Catholic. Both of these had little enough in common with the sharecropper, illiterate and bur dened with debt, perhaps dreaming of a North where—rumor had it—a man could make a better living and gain a margin of respect. There was Marcus Garvey, costumes and oratory fantastic, wooing the Black masses with visions of Africa and race glory while Father Divine promised them a bi-racial heaven presided over by a Black god. Yet no history of the time should leave out that apostle of occupational training and booster of business, Robert Russa Moton. And perhaps a place should be made for William S. Braithwaite, an aesthete so anonymously genteel that few of his White readers realized he was Black. These were men very different from Langston Hughes and the other Harlem poets who were finding music in their heritage while rejecting capitalistic America (whose chil dren and refugees they were). And, in this confusion of voices, who was there to speak for the broken and degraded like the pitiful old man, born in slavery ninety-two years before, paraded by a Mississippi chap ter of the American Legion in front of the national convention of 1923 with a sign identifying him as the "Champeen Chicken Thief of the Con federate Army"?2 In this cacaphony, and through these decades of alternate boom and bust, one particular voice retained a consistent message, though condi tions might prove the message itself to be inconsistent. -

Jackie Robinson's Original 1945 Montreal Royals and Original 1947

OLLECTORS CAFE PRESENTS Jackie Robinson’s Original 1945 Montreal Royals and Original 1947 Brooklyn Dodgers Contracts Founding Documents of the Civil Rights Movement OLLECTORS CAFE The Global, Lifestyle, Collectibles Brand is Coming! The Collectibles and Memorabilia industry is a $250+ billion dollar per year global market that is substantially fragmented with no one entity owning more than one half of one percent of market share. Further, there is NO MEETING PLACE for collectors to gather with other like minded collectors socially, and display their passion for their own collections. Lastly, there is no place to purchase all categories of collectibles, under one trusted umbrella, in a safe, AUTHENTICITY INSURED, environment. This is all about to change with the launch of the Collectors Cafe Company, where “PRE-APPRAISED, “PRE-AUTHENTICATED” and “PRE-INSURED” collectibles will be coming soon. Through the invention of AUTHENTICITY INSURANCE by company founder Mykalai Kontilai, Collectors Cafe has successfully executed agreements with some of the largest insurance companies who will underwrite all collectibles offered on the website. Lloyds of London (Hiscox), AIG, Liberty Mutual, Chubb, C.V Starr, Navigators, and XL are all exclusive underwriters and partners. This amazing accomplishment, we believe, will spark a COLLECTIBLES REVOLUTION, which will begin to consolidate the industry through the first online and global “One-Stop Shop” for buying, selling, and social networking for the entire collectibles market place. Driving the brand will be a plethora of multi-media assets, including but not limited to, the Collectors Cafe TV Series, The Collectors Cafe Blogger Network, The Collectors Tube Digital Content Platform, The Collectors Cafe Celebrity Collector Portal, The Collectors Cafe Master Dealer Network, and the Collectors Cafe IP Portfolio. -

"Ssst Setoice Vitozd&U

(PHOSE ssr>o) Thursday. May 27, 1913 PAGE 36 DETROIT EVENING TIMES CHEEKY Test Passed Lost and Found Male Help Wanted I rges Hubs BLACK Mlfold: valuable papere and MARRIAGES—DEATHS—DIVORCES money: reward, 0. F. Moaea. Bombers Blast Aill Hod Cross Tons of Bombs llv Dahlgrcii Murray 3(0. BROOCH—Topaz, aet In silver: loat Fri- day: keepsake Reward. Trinity 2-3421. NEW* YORK. May 27 (UP) PHILADELPHIA, May 27 »INS) MARRIAGE LICENSES DEATHS 5.300 public and Bahe Dahlgren. shortstop and Sidney Howard, ftl; Martha Well*, 50. Roy Harwood. 29# Winder 31 LOST—Billfold containing A and C book. The nation’s Rmald W. Powers. 24, Ethel m. Hyre. 1* Amanda Stoner. 200« t Fifth 73 registration card, car inspactlon report, urged Jap leading hitter for the Phillies, registration private goll course* were h> Base 1 Manley A Brady Deathetfge. 33*# K. Varnor High- driver'* license and draft Blast Grabowakl. 33. Edith I.anrfi. 31 Resistance today successfully passed his Tony Angela way . Vicinity Reward. Tem- J. 5.%. Eastern Market Attention Last had Adragna, 25. Ruggtrello, George president 1 W. Blossom Jr. Hattie ratter»..n 3182 Shirman 30. ple 2*0384 or Oregon *919. Golf first physical examination for the •19 _____ of the I'nited State* Associ- Ed (Juellelte NX; Alice Ki*. Uenet Walla, e 2228 Chene, .A 3 army. 54. LOST— Friday, oval pin. open ation. today to hold Red i i os- Delbert H June* 23: Paulin# Pavlik. 23. Mary Carroll, 2412 Newton. 70 Good center. draft hoard Dyke. Reward. Townsend 5-10*6 tournament* thi- week-end. -

EXTENSIONS of REMARKS September 23, 1969 EXTENSIONS of REMARKS

26744 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS September 23, 1969 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS CHANGING CHALLENGE IN HIGH centrated on the execution of the Interstate assessing the impact of land use of highway WAY DEVELOPMENT STRESSED highway program. Before we have completed construction, urban redevelopment, mining BY SENATOR RANDOLPH IN AD it sometime in the middle of the next dec and sanitary landfills. We are looking at the DRESS AT VIRGINIA MOTOR VE ade we will have spent approximately $70 bil question of biological imbalances created by lion on this massive public works under dredging, thermal pollution, pesticides, and HICLE CONFERENCE taking, begun 48 years ago. By then we will air pollution. And we are probing problems have achieved our goal of connecting every connected with flooding and dam construc major metropolitan center in the United tion, the effects of building reservoirs, and HON. WILLIAM B. SPONG, JR. States in a coast-to-coast and border-to the use of nuclear energy for power or con OF VIRGINIA border hook-up. struction. IN THE SENATE OF THE UNITED STATES In the process of building our 42,500 miles The heart of our concern is best reflected in of Interstate and Defense highways, we will Tuesday, September 23, 1969 legislation introduced early this year by have produced vast wealth in the form of myself and 41 of my colleagues, the "En Mr. SPONG. Mr. President, this morn new homes, new plants, and new jobs. We vironmental Quality Improvement Act of ing the Virginia Motor Vehicle Confer will have repeated many times over the suc 1969," which has been incorporated in S. -

JUMPING SHIP: the DECLINE of BLACK REPUBLICANISM in the ERA of THEODORE ROOSEVELT, 1901—1908 a Thesis Presented to the Graduat

JUMPING SHIP: THE DECLINE OF BLACK REPUBLICANISM IN THE ERA OF THEODORE ROOSEVELT, 1901—1908 A Thesis Presented to The Graduate Faculty of The University of Akron In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts Mark T. Tomecko August, 2012 JUMPING SHIP: THE DECLINE OF BLACK REPUBLICANISM IN THE ERA OF THEODORE ROOSEVELT, 1901—1908 Mark T. Tomecko Thesis Approved: Accepted: _______________________________ ______________________________ Advisor Dean of the College Dr. Tracey Jean Boisseau Dr. Chand Midha _______________________________ ______________________________ Department Chair Dean of the Graduate School Dr. Martin Wainwright Dr. George Newkome ______________________________ Date ii ABSTRACT Most analysts of black voting patterns in the United States have assumed that the first substantive abandonment of the Republican party by black voters occurred in the 1930s, when the majority of black voters embraced Franklin Roosevelt‘s New Deal. A closer examination, however, of another Roosevelt presidency – that of Theodore Roosevelt (1901-1909) – demonstrates the degree to which black voters were already growing disenchanted with the Republicans in the face of what they viewed as uneven support and contradictory messages from the highest ranking Republican in the land. Though the perception of Theodore Roosevelt‘s relationship to black Americans has been dominated by his historic invitation of Booker T. Washington to dine with him at the White House in 1901, in fact even this event had assorted and complex meanings for Roosevelt‘s relationship to the black community. More importantly, his dismissal of black troops following a controversial shooting in southern Texas in 1906 – an event known as the Brownsville affair – set off a firestorm of bitter protest from the black press, black intellectuals, and black voters. -

For Neoes on Newspapers

Careers For Neoes On Newspapers * What's Happening, * What the Jobs Are r * How Jobs Can Be Found nerican Newspaper Guild (AFL-CIO, CLC) AMERICAN NEWSPAPER GUILD (AFL-CIO, CLC) Philip Murray Building * 1126 16th Street N.W. Washington, D.C. 20036 PRESIDENT: ARTHUR ROSENSTOCK EXECUTIVE VICE PRESIDENT: WILLIAM J. FARSON SECRETARY-TREASURER: CHARLES A. PERLIK, JR REGIONAL VICE PRESIDENTS Region 1 DANIEL A. McLAUGHLIN, North Jersey Region 4 ROBERT J. HICKEY, Son Jose Region 2 RICHARD LANE, Memphis Region 5 EDWARD EASTON, JR., New York Region 3 JAMES B. WOODS, St. Louis Region 6 WILLIAM H. McLEMAN, Vancouver VICE PRESIDENTS AT LARGE JACK DOBSON, Toronto MARSHALL W. SCHIEWE, Chicago GEORGE MULDOWNEY, Wire Service NOEL WICAL, Cleveland KENNETH RIEGER, Toledo HARVEY H. WING, San Francisco-Oakland . Ws.. - Ad-AA1964 , s\>tr'id., ofo} +tw~ i 7 I0Nle0 Our newspapers, which daily report the rising winds of the fight for equal rights of minority groups, must now take a first hand active part in that fight as it affects the hiring, promotion, and upgrading of newspaper employes In order to improve the circumstances of an increas- ing number of minority-group people, who are now turned aside as "unqualified" for employment and pro- motion, we seek . a realistic, down-to-earth meaning- ful program, which will include not merely the hiring of those now qualified without discrimination as to race, age, sex, creed, color, national origin or ancestry, but also efforts through apprenticeship training and other means to improve and upgrade their qualifications. Human Rights Report American Newspaper Guild Convention Philadelphia, July 8 to 12, 1963 RELATIONSorLIS"WY JUL 23196 OF CALFORNIA UHI4Rt5!y*SELY NEWSPAPER jobs in the United States are opening to Negroes for the first time. -

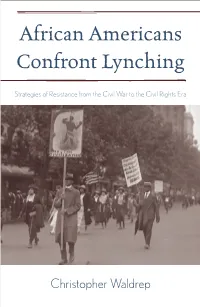

African Americans Confront Lynching: Strategies of Resistance from The

African Americans Confront Lynching Strategies of Resistance from the Civil War to the Civil Rights Era Christopher Waldrep StrategiesofResistance.indd 1 9/30/08 11:52:02 AM African Americans Confront Lynching The African American History Series Series Editors: Jacqueline M. Moore, Austin College Nina Mjagkij, Ball State University Traditionally, history books tend to fall into two categories: books academics write for each other, and books written for popular audiences. Historians often claim that many of the popu- lar authors do not have the proper training to interpret and evaluate the historical evidence. Yet, popular audiences complain that most historical monographs are inaccessible because they are too narrow in scope or lack an engaging style. This series, which will take both chronolog- ical and thematic approaches to topics and individuals crucial to an understanding of the African American experience, is an attempt to address that problem. The books in this series, written in lively prose by established scholars, are aimed primarily at nonspecialists. They fo- cus on topics in African American history that have broad significance and place them in their historical context. While presenting sophisticated interpretations based on primary sources and the latest scholarship, the authors tell their stories in a succinct manner, avoiding jargon and obscure language. They include selected documents that allow readers to judge the evidence for themselves and to evaluate the authors’ conclusions. Bridging the gap between popular and academic history, these books bring the African American story to life. Volumes Published Booker T. Washington, W.E.B. Du Bois, and the Struggle for Racial Uplift Jacqueline M. -

National Pastime a REVIEW of BASEBALL HISTORY

THE National Pastime A REVIEW OF BASEBALL HISTORY CONTENTS The Chicago Cubs' College of Coaches Richard J. Puerzer ................. 3 Dizzy Dean, Brownie for a Day Ronnie Joyner. .................. .. 18 The '62 Mets Keith Olbermann ................ .. 23 Professional Baseball and Football Brian McKenna. ................ •.. 26 Wallace Goldsmith, Sports Cartoonist '.' . Ed Brackett ..................... .. 33 About the Boston Pilgrims Bill Nowlin. ..................... .. 40 Danny Gardella and the Reserve Clause David Mandell, ,................. .. 41 Bringing Home the Bacon Jacob Pomrenke ................. .. 45 "Why, They'll Bet on a Foul Ball" Warren Corbett. ................. .. 54 Clemente's Entry into Organized Baseball Stew Thornley. ................. 61 The Winning Team Rob Edelman. ................... .. 72 Fascinating Aspects About Detroit Tiger Uniform Numbers Herm Krabbenhoft. .............. .. 77 Crossing Red River: Spring Training in Texas Frank Jackson ................... .. 85 The Windowbreakers: The 1947 Giants Steve Treder. .................... .. 92 Marathon Men: Rube and Cy Go the Distance Dan O'Brien .................... .. 95 I'm a Faster Man Than You Are, Heinie Zim Richard A. Smiley. ............... .. 97 Twilight at Ebbets Field Rory Costello 104 Was Roy Cullenbine a Better Batter than Joe DiMaggio? Walter Dunn Tucker 110 The 1945 All-Star Game Bill Nowlin 111 The First Unknown Soldier Bob Bailey 115 This Is Your Sport on Cocaine Steve Beitler 119 Sound BITES Darryl Brock 123 Death in the Ohio State League Craig -

African American Newspapers, Series 1, 1827-1998 an Archive of Americana Collection

African American Newspapers, Series 1, 1827-1998 An Archive of Americana Collection Quick Facts Titles, drawn from more than 35 states, provide a one-of-a-kind record of African American history, culture and daily life Covers life in the Antebellum South, the Jim Crow Era, the Great Migration, Harlem Renaissance, Civil Rights movement, and more Based upon James P. Danky’s monumental bibliography: African-American Newspapers and Periodicals “...full-text access to 270 historically significant African-American newspapers from across the U.S....this collection offers unique perspectives and rich historical context...Highly recommended.” —L. A. Ganster, University of Pittsburgh in Choice (January 2011) Overview African American Newspapers, Series 1, 1827-1998, provides online access to 280 U.S. newspapers chronicling a century and a half of the African American experience. This unique collection, which includes papers from more than 35 states, features many rare and historically significant 19th-century titles. Newly digitized, these newspapers published by or for African Americans can now be browsed and searched as never before. Hundreds of titles—all expertly selected from leading repositories Part of the Readex America’s Historical Newspapers collection, African American Newspapers, Series 1, was created from the most extensive African American newspaper archives in the United States—those of the Wisconsin Historical Society, Kansas State Historical Society and the Library of Congress. Selections were guided by James Danky, editor of African-American Newspapers and Periodicals: A National Bibliography. Beginning with Freedom’s Journal (NY)—the first African American newspaper published in the United States—the titles in this resource include The Colored Citizen (KS), Arkansas State Press, Rights of All (NY), Wisconsin Afro-American, New York Age, L’Union (LA), Northern Star and Freeman’s Advocate (NY), Richmond Planet, Cleveland Gazette, The Appeal (MN) and hundreds of others from every region of the U.S. -

The Lynching of Cleo Wright

University of Kentucky UKnowledge United States History History 1998 The Lynching of Cleo Wright Dominic J. Capeci Jr. Missouri State University Click here to let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Thanks to the University of Kentucky Libraries and the University Press of Kentucky, this book is freely available to current faculty, students, and staff at the University of Kentucky. Find other University of Kentucky Books at uknowledge.uky.edu/upk. For more information, please contact UKnowledge at [email protected]. Recommended Citation Capeci, Dominic J. Jr., "The Lynching of Cleo Wright" (1998). United States History. 95. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/upk_united_states_history/95 The Lynching of Cleo Wright The Lynching of Cleo Wright DOMINIC J. CAPECI JR. THE UNIVERSITY PRESS OF KENTUCKY Publication of this volume was made possible in part by a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities. Copyright © 1998 by The University Press of Kentucky Scholarly publisher for the Commonwealth, serving Bellarmine College, Berea College, Centre College of Kentucky, Eastern Kentucky University, The Filson Club Historical Society, Georgetown College, Kentucky Historical Society, Kentucky State University, Morehead State University, Murray State University, Northern Kentucky University, Transylvania University, University of Kentucky, University of Louisville, and Western Kentucky University. All rights reserved Editorial and Sales Offices: The University Press of Kentucky 663 South Limestone Street, Lexington, Kentucky 40508-4008 02 01 00 99 98 5 4 3 2 1 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Capeci, Dominic J. The lynching of Cleo Wright / Dominic J. Capeci, Jr. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. -

Cabrera, Lorenzo 1941-1943 Club Contramaestre (Cuba)

Cabrera, Lorenzo 1941-1943 Club Contramaestre (Cuba) (Chiquitin) 1944-1945 Regia de la Liga de Verano 1946-1948 New York Cubans (NNL) 1949-1950 New York Cubans (NAL) 1950 Mexico City (Mexican League) (D) 1951 Oakland Oaks (PCL) 1951 Ottawa (IL) 1951 Club Aragua (Mexican Pacific Coast League) 1952 El Escogido (Dominican Summer League) 1953 Aguilas Cibaenas (Dominican Summer League) 1954 Del Rio (Big State League) 1955 Port Arthur (Big State League) 1956 Tijuana-Nogales (Arizona-Mexico League) 1956 Mexico City Reds (Mexican League) 1957 Combinado (Nicaraguan League) 1957 Granada (Nicaraguan League) Winter Leagues: 1942-1943 Almendares (Cuba) 1946-1947 Marianao (Cuba) 1947-1948 Marianao (Cuba) 1948-1949 Marianao (Cuba) 1949-1950 Marianao (Cuba) 1950-1951 Marianao (Cuba) 1951 Habana (Caribbean World Series - Caracas) (Second Place with a 4-2 Record) 1951-1952 Marianao (Cuba) 1952-1953 Marianao (Cuba) 1953 Cuban All Star Team (American Series - Habana, Cuba) (Cuban All Stars vs Pittsburgh Pirates) (Pirates won series 6 games to 4) 1953-1954 Havana (Cuba) 1953-1954 Marianao (Cuba) 1954-1955 Cienfuegos (Cuba) 1955-1956 Cienfuegos (Cuba) Verano League Batting Title: (1944 - Hit .362) Mexican League Batting Title: (1950 - Hit .354) Caribbean World Series Batting Title: (1951 - Hit .619) (All-time Record) Cuban League All Star Team: (1950-51 and 1952-53) Nicaraguan League Batting Title (1957 – Hit .376) Cuban Baseball Hall of Fame (1985) 59 Caffie, Joseph Clifford (Joe) 1950 Cleveland Buckeyes (NAL) 1950 Signed by Cleveland Indians (MLBB) 1951 Duluth Dukes (Northern League) 1951 Harrisburg Senators (Interstate League) 1952 Duluth Dukes (Northern League) 1953 Indianapolis Indians (AA) 1953 Reading Indians (Eastern League) 1954-1955 Indianapolis Indians (AA) 1955 Syracuse Chiefs (IL) 1956 Buffalo Bisons (IL) 1956 Cleveland Indians (ML) 1956 San Diego Padres (PCL) 1957 Buffalo Bisons (IL) 1957 Cleveland Indians (ML) 1958-1959 Buffalo Bisons (IL) 1959 St. -

The National Constitution Center to Display Signed Contracts of Baseball Legend and Civil Rights Advocate Jackie Robinson for a Limited Time

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE THE NATIONAL CONSTITUTION CENTER TO DISPLAY SIGNED CONTRACTS OF BASEBALL LEGEND AND CIVIL RIGHTS ADVOCATE JACKIE ROBINSON FOR A LIMITED TIME Contracts to be on display from May 26-June 5, 2016 Philadelphia, PA (May 19, 2016) – The historic documents that led to the breaking of baseball’s color barrier will be on display at the National Constitution Center for a limited time only next Thursday, May 26 through Sunday, June 5. The documents will arrive in Philadelphia as part of the Collectors Cafe Freedom Tour, less than two months after the Philadelphia City Council passed a resolution apologizing for the racism Robinson experienced during his visit to the city in 1947. On April 11, 1947, Jack Roosevelt Robinson signed a contract with the Brooklyn Dodgers, leading to the integration of Major League Baseball. This contract, in addition to the contract he signed in 1945 when he joined the minor league team the Montreal Royals, will be on display at the National Constitution Center. Jackie Robinson (1919–1972) became the first African American to play major league baseball after Brooklyn Dodgers President Branch Rickey chose him to integrate baseball. Facing antagonism both on and off the field―from fans, opposing teams, and even initially his own teammates―Robinson displayed astounding fortitude and dazzled the crowds on the field and at bat during his first season with the Dodgers, earning the first-ever Rookie of the Year Award. He retired with a career batting average of .311, 1,518 hits, 137 home runs, 734 RBIs, and 197 stolen bases and was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame on the first ballot in his first year of eligibility (1962).